Thu, Jan 29, 2026

Volume 36, Issue 1 (1-2026)

JHNM 2026, 36(1): 92-82 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hamed-Biabani M, Abdolalipour S, Khalili-Azar K, Heidarabadi S, Mirghafourvand M. Risk Factors of Developmental Delay in Children Under 5 Years Old in Tabriz: A Case-control Study. JHNM 2026; 36 (1) :92-82

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2447-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2447-en.html

Monireh Hamed-Biabani1

, Somayeh Abdolalipour2

, Somayeh Abdolalipour2

, Khadijeh Khalili-Azar3

, Khadijeh Khalili-Azar3

, Seifollah Heidarabadi4

, Seifollah Heidarabadi4

, Mojgan Mirghafourvand *5

, Mojgan Mirghafourvand *5

, Somayeh Abdolalipour2

, Somayeh Abdolalipour2

, Khadijeh Khalili-Azar3

, Khadijeh Khalili-Azar3

, Seifollah Heidarabadi4

, Seifollah Heidarabadi4

, Mojgan Mirghafourvand *5

, Mojgan Mirghafourvand *5

1- Midwifery (MSc), Department of Midwifery, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

2- Assistant Professor, Department of Midwifery, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

3- Nursing (MSc), Department of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Pediatric Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

5- Professor, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. ,mirghafourvand@gmail.com

2- Assistant Professor, Department of Midwifery, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

3- Nursing (MSc), Department of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Pediatric Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

5- Professor, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 565 kb]

(69 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (174 Views)

Full-Text: (5 Views)

Introduction

Developmental Delay (DD) in children refers to a condition in which a child under five years fails to achieve expected developmental milestones compared to peers in one or more domains, including motor, language, cognitive, social, or emotional skills [1]. The DD can cause persistent difficulties in learning, communication, and daily functioning, resulting in long-term educational and social challenges and imposing emotional and financial burdens on families [2-5]. The global prevalence of DD is high, especially in low- and middle-income countries, with a pooled prevalence of 18.83% [3]. In Iran, the reported prevalence ranges from 4.3% to 26%, depending on age and assessment methods [4]. Early detection and intervention during the first years of life are critical to reduce DD [2].

Child development is influenced by various biological, socioeconomic, maternal, and environmental factors [6]. In the prenatal period, the risk factors include genetic disorders, maternal infections (such as rubella, cytomegalovirus, and toxoplasma), and exposure to drugs or toxins [7]. In the perinatal and postnatal periods, the risk factors include preeclampsia, Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR), asphyxia, hypoglycemia, meningitis, and trauma [8, 9]. Family and environmental factors such as low parental education, poverty, large family size, and lack of stimulating home environments further increase the risk of DD [10, 11]. Biological factors including preterm birth and low birth weight are strongly linked with motor, cognitive, and behavioral problems [12-16]. Maternal characteristics also play a major role. Children born to teenage mothers or to mothers with depression, stress, or chronic conditions such as diabetes or thyroid disorders have poorer developmental outcomes [17-24]. Moreover, maternal mental health and proper prenatal care significantly influence children’s neurocognitive growth and social adjustment [17-19].

Despite extensive research, several aspects of DD remain unclear [2]. Considering the high prevalence and serious long-term consequences of DD, identifying modifiable risk factors is essential for its prevention and early intervention. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate predictors of DD among children under five years old in Tabriz, Iran.

Materials and Methods

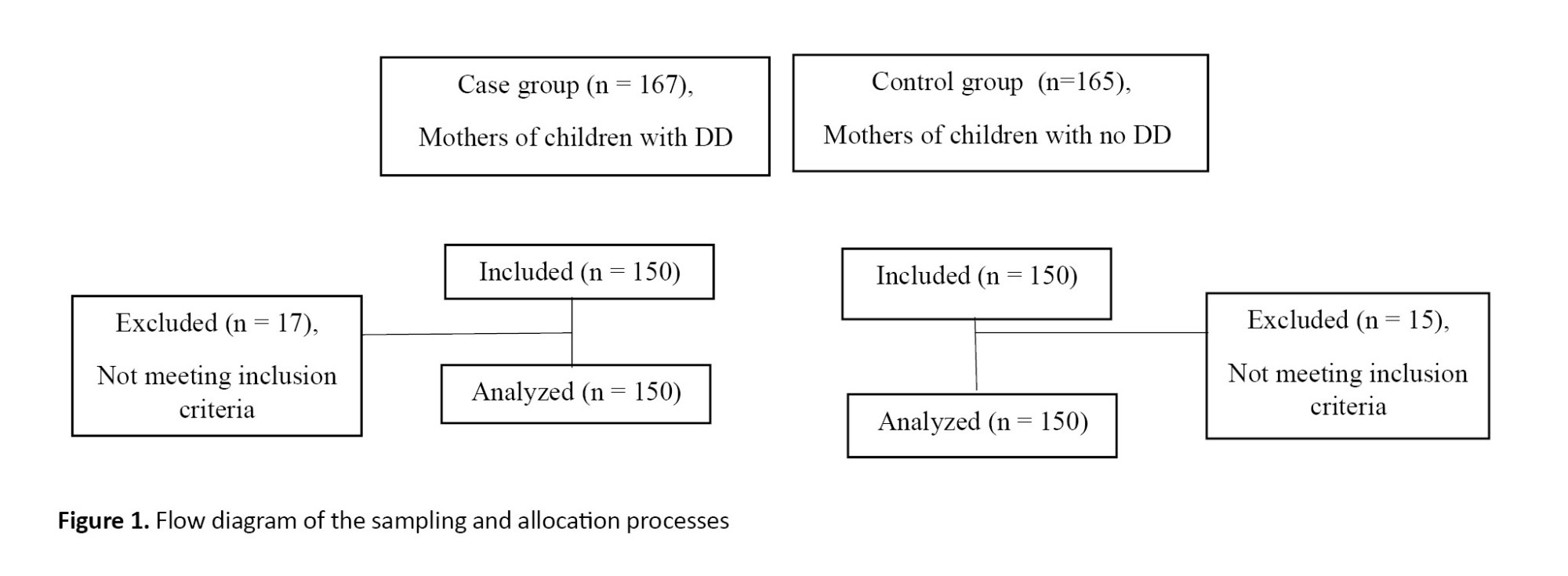

This case-control study was conducted from January to August 2022. The case group included mothers of children diagnosed with DD by a pediatrician in the Comprehensive Development Center in Tabriz, Iran. They were selected via convenience sampling. The control group included mothers of children under five years without DD, referred to health centers in Tabriz. They were selected via cluster sampling and the simple random sampling method using the Random Website [25]. First, a quarter (20 centers) of the 80 health centers in Tabriz were randomly selected. From each center, participants were randomly selected using a computer program and based on the determined sample size. The appropriate sample size for each selected center was calculated as a fraction of the total sample size, according to the demographics of the center. The researcher contacted the parents by phone to briefly explain the study objectives and methodology to them and invite them. Considering that most study variables were related to children’s characteristics (15 items) and that 10 samples were accounted for per item [26], the sample size was estimated at 150 per group. The inclusion criterion was having a child under five years. Children with congenital abnormalities or intellectual disability were excluded. The outcome was DD and exposures included socio-demographic variables. Matching was conducted based on the children’s ages in both groups. Each case was matched with one control, resulting in a 1:1 ratio. Figure 1 shows the sampling process.

Developmental Delay (DD) in children refers to a condition in which a child under five years fails to achieve expected developmental milestones compared to peers in one or more domains, including motor, language, cognitive, social, or emotional skills [1]. The DD can cause persistent difficulties in learning, communication, and daily functioning, resulting in long-term educational and social challenges and imposing emotional and financial burdens on families [2-5]. The global prevalence of DD is high, especially in low- and middle-income countries, with a pooled prevalence of 18.83% [3]. In Iran, the reported prevalence ranges from 4.3% to 26%, depending on age and assessment methods [4]. Early detection and intervention during the first years of life are critical to reduce DD [2].

Child development is influenced by various biological, socioeconomic, maternal, and environmental factors [6]. In the prenatal period, the risk factors include genetic disorders, maternal infections (such as rubella, cytomegalovirus, and toxoplasma), and exposure to drugs or toxins [7]. In the perinatal and postnatal periods, the risk factors include preeclampsia, Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR), asphyxia, hypoglycemia, meningitis, and trauma [8, 9]. Family and environmental factors such as low parental education, poverty, large family size, and lack of stimulating home environments further increase the risk of DD [10, 11]. Biological factors including preterm birth and low birth weight are strongly linked with motor, cognitive, and behavioral problems [12-16]. Maternal characteristics also play a major role. Children born to teenage mothers or to mothers with depression, stress, or chronic conditions such as diabetes or thyroid disorders have poorer developmental outcomes [17-24]. Moreover, maternal mental health and proper prenatal care significantly influence children’s neurocognitive growth and social adjustment [17-19].

Despite extensive research, several aspects of DD remain unclear [2]. Considering the high prevalence and serious long-term consequences of DD, identifying modifiable risk factors is essential for its prevention and early intervention. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate predictors of DD among children under five years old in Tabriz, Iran.

Materials and Methods

This case-control study was conducted from January to August 2022. The case group included mothers of children diagnosed with DD by a pediatrician in the Comprehensive Development Center in Tabriz, Iran. They were selected via convenience sampling. The control group included mothers of children under five years without DD, referred to health centers in Tabriz. They were selected via cluster sampling and the simple random sampling method using the Random Website [25]. First, a quarter (20 centers) of the 80 health centers in Tabriz were randomly selected. From each center, participants were randomly selected using a computer program and based on the determined sample size. The appropriate sample size for each selected center was calculated as a fraction of the total sample size, according to the demographics of the center. The researcher contacted the parents by phone to briefly explain the study objectives and methodology to them and invite them. Considering that most study variables were related to children’s characteristics (15 items) and that 10 samples were accounted for per item [26], the sample size was estimated at 150 per group. The inclusion criterion was having a child under five years. Children with congenital abnormalities or intellectual disability were excluded. The outcome was DD and exposures included socio-demographic variables. Matching was conducted based on the children’s ages in both groups. Each case was matched with one control, resulting in a 1:1 ratio. Figure 1 shows the sampling process.

The data collection instrument was a researcher-made questionnaire surveying sociodemographic/clinical/ obstetric characteristics of the mothers and the characteristics of their children. The questionnaire was reviewed and confirmed based on the opinions of a panel of experts, including pediatricians and developmental specialists. Socio-demographic characteristics included parents’ age and educational level, family’s monthly income, mother’s occupation, type of marriage, and parents’ history of tobacco and hookah use. Clinical/obstetric characteristics included gravida, pregnancy method, type of delivery, history of chronic diseases before pregnancy, history of disorders during pregnancy (pre-eclampsia or high blood pressure, gestational diabetes, anemia, thyroid disease, depression, and receiving medication for them), and maternal use of iron, folic acid, and other drugs. Child-related characteristics included gender and age of the child, gestational age at birth, IUGR in the child, wanted/unwanted child, use of iron, multivitamin or A+D drops by the child, breastfeeding the child, reading books to the child, child sleep time, child play time, blaming or punishment of the child, and history of prolonged icterus, metabolic diseases, and hospitalization.

The Ages and Stages Questionnaires - Third Edition (ASQ-3) was also used in this study [27] to diagnose the DD in children. This instrument contains 19 items to screen for DD in children aged 4-60 months. It has five domains (communication, problem-solving, personal-social skills, fine motor, and gross motor), each with six items. Parents can answer the questions with “yes, (10 points)”, “sometimes, (5 points)”, or “not yet (0 points)”. The total score for each domain ranges from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate better performance in that domain. The scores for each domain are summed up to obtain the questionnaire’s total score, which is then plotted against the cutoff point to determine whether the child is on schedule, needs monitoring, or requires further assessment. A score above the cutoff point indicates that the child’s development in that domain is on schedule. A score equal to or below the cutoff point suggests possible risk of DD and the need for further evaluation or intervention. The overall developmental status is therefore coded as a binary variable: 1=DD and 0=normal development [27]. The adaptation and standardization of the Persian version were conducted in Iran by Vameghi et al., who demonstrated the test’s ability to detect DD at >96% [28].

After providing comprehensive information about the study objectives, benefits, results, and confidentiality of the information during a face-to-face visit with the participants, their informed consent was obtained. The questionnaires were then completed through interviews with mothers, ensuring complete responses from all participants. The collected data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 24. The dependent variable was developmental status (1=case with DD, 0=control without DD), and the independent variables were socio-demographic, clinical, obstetric, and child characteristics. To determine the relationship of these characteristics with DD, an independent t-test, chi-square test, and Chi-square for trend (linear-by-linear association) were used in bivariate analysis. Multivariable logistic regression using the enter method in a single-step analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of DD.

Results

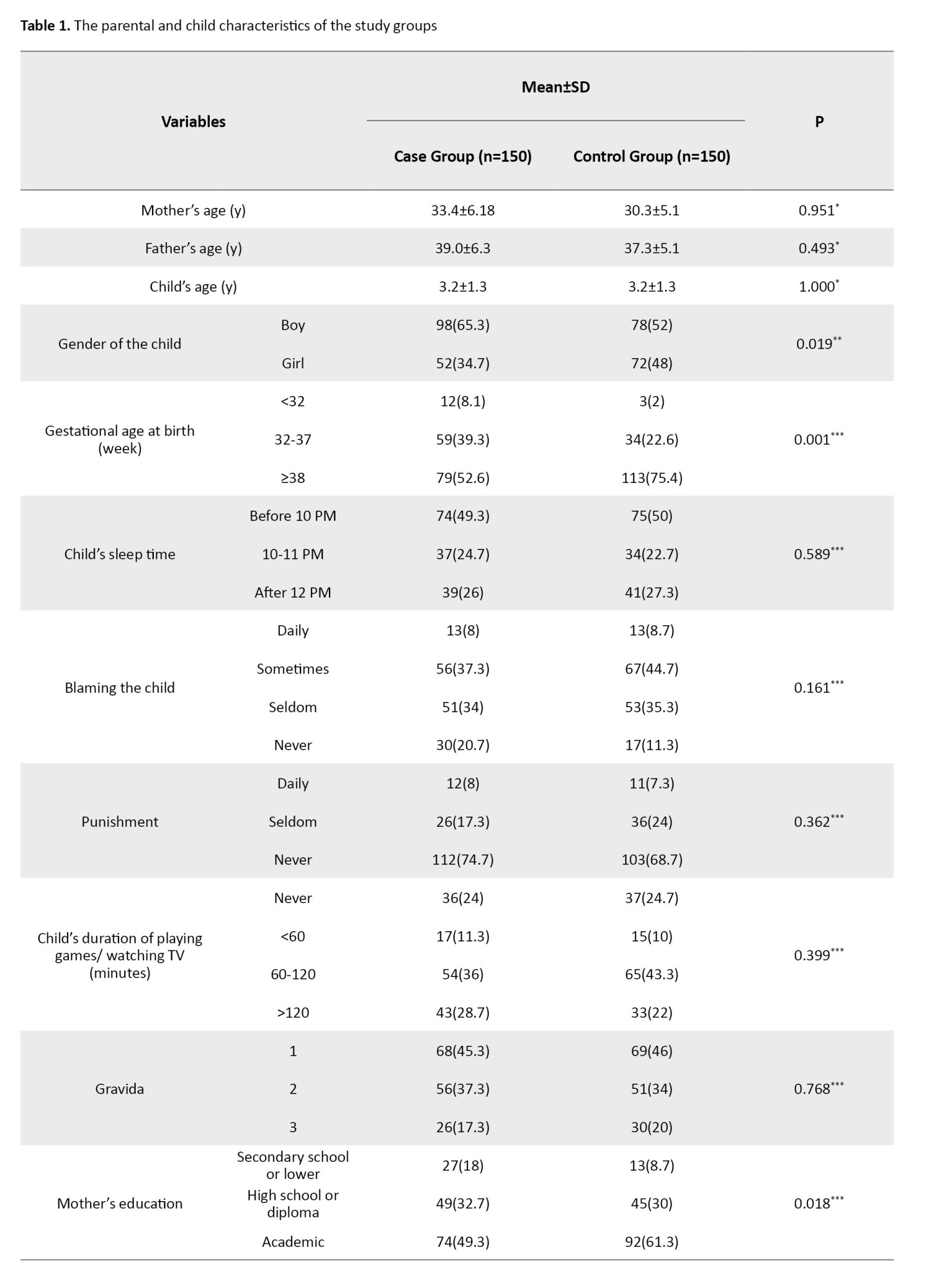

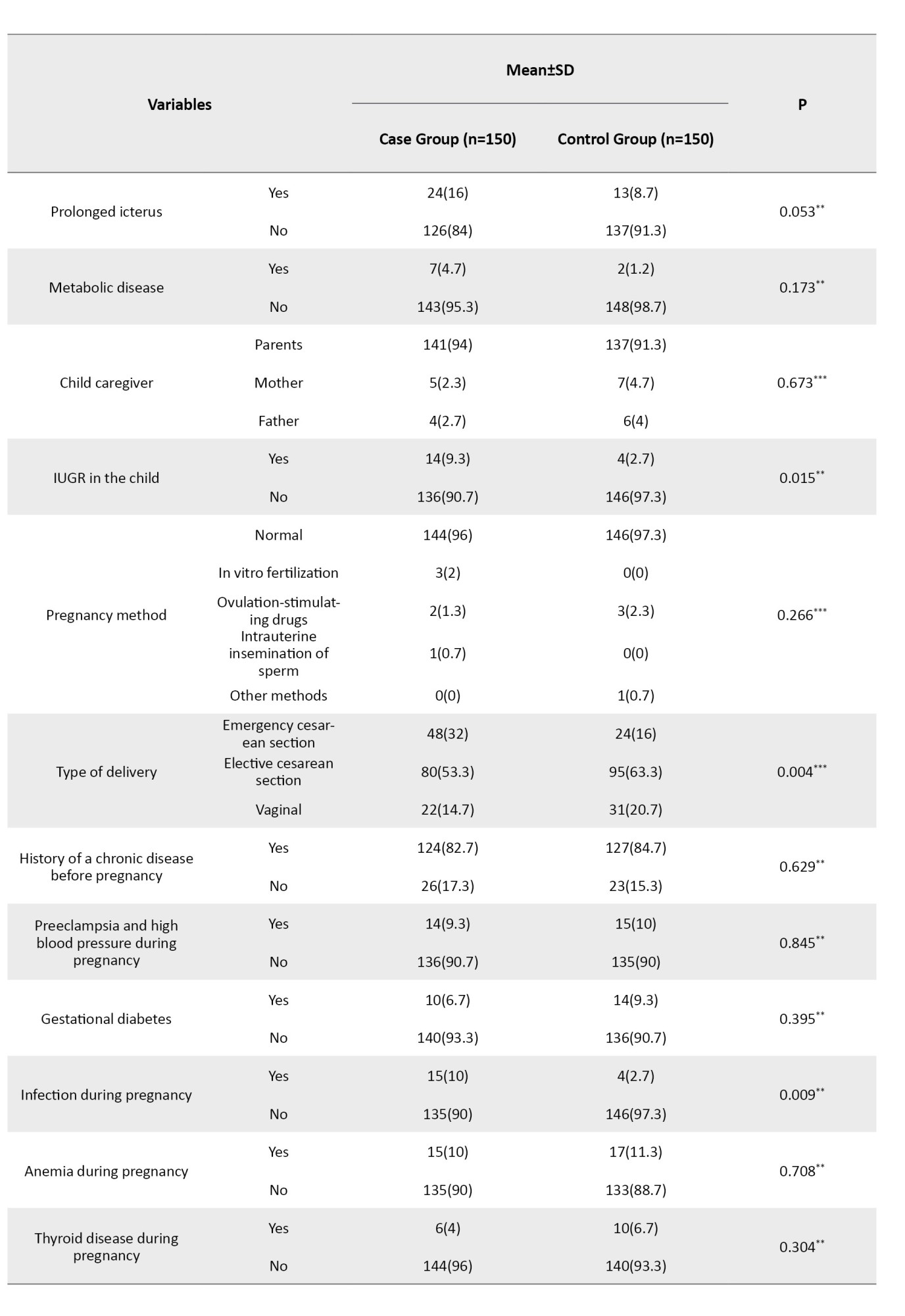

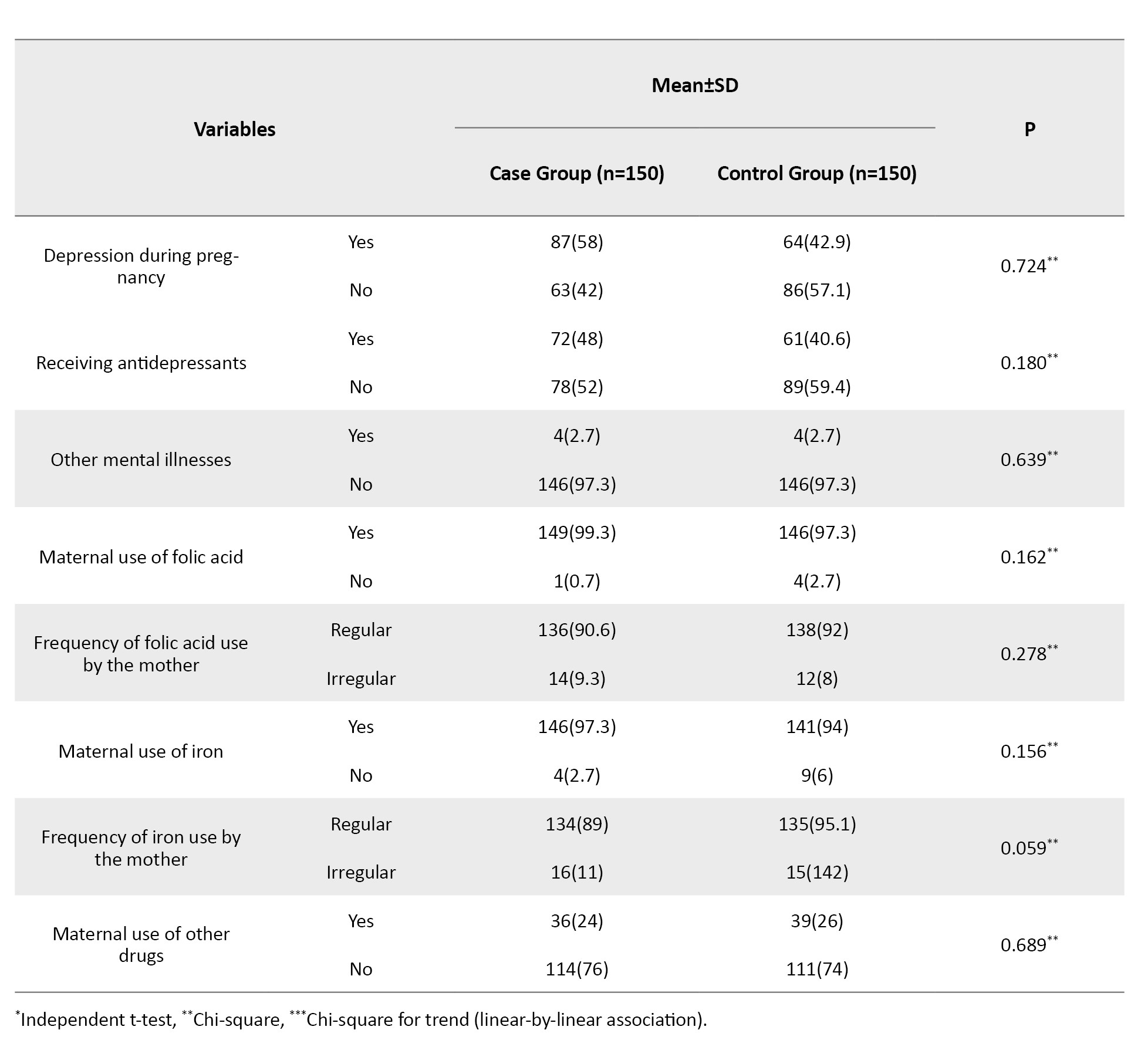

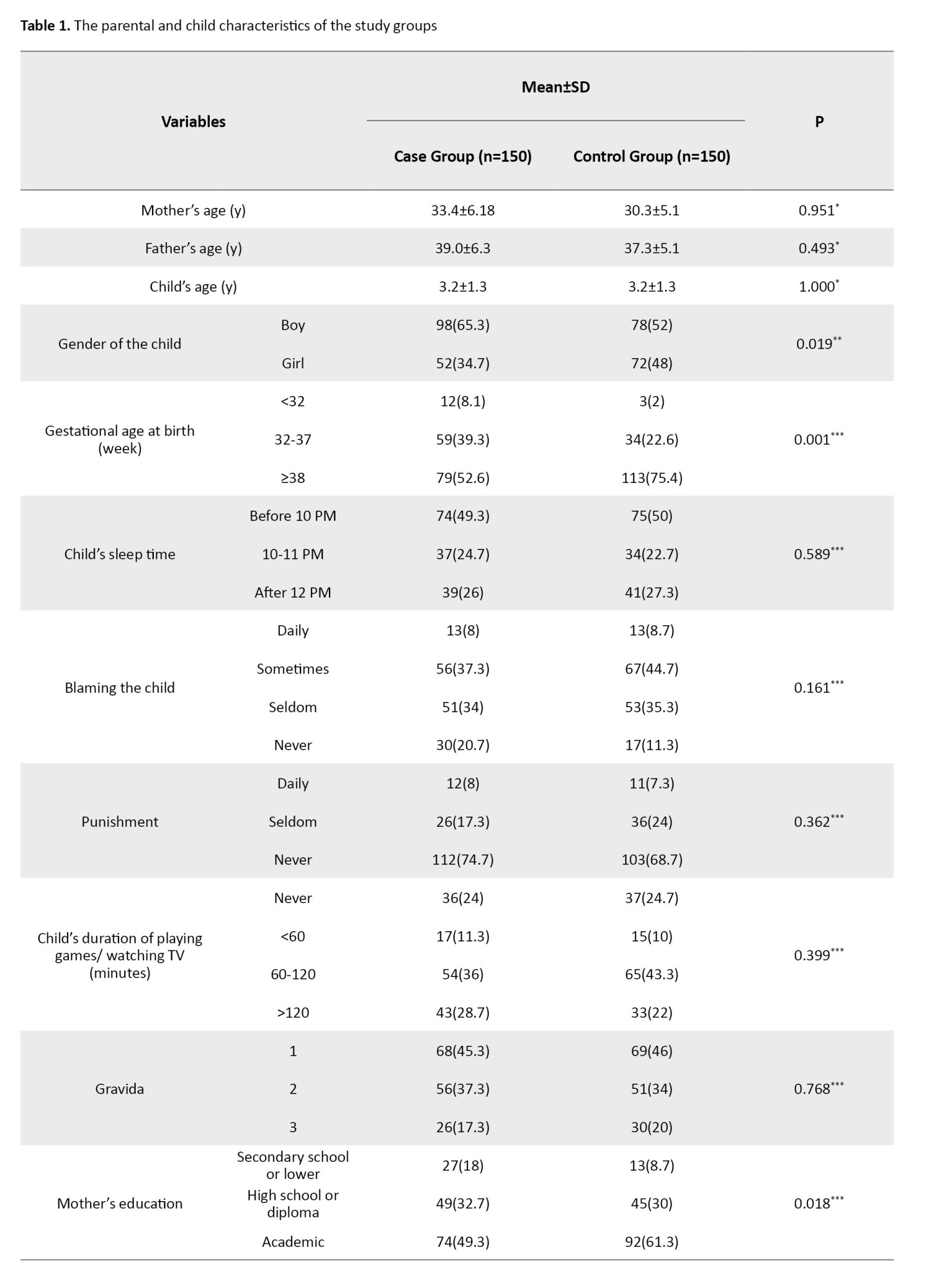

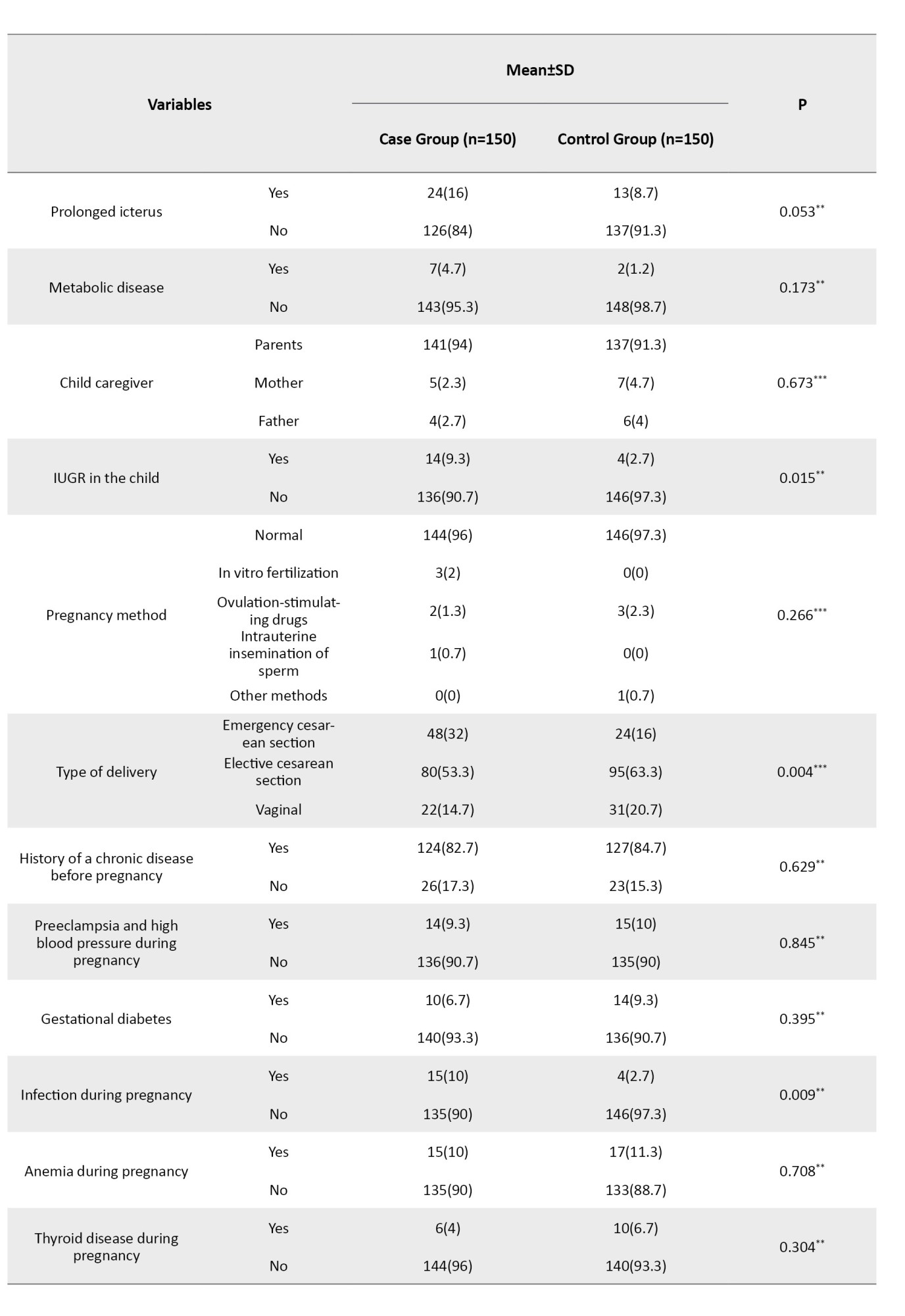

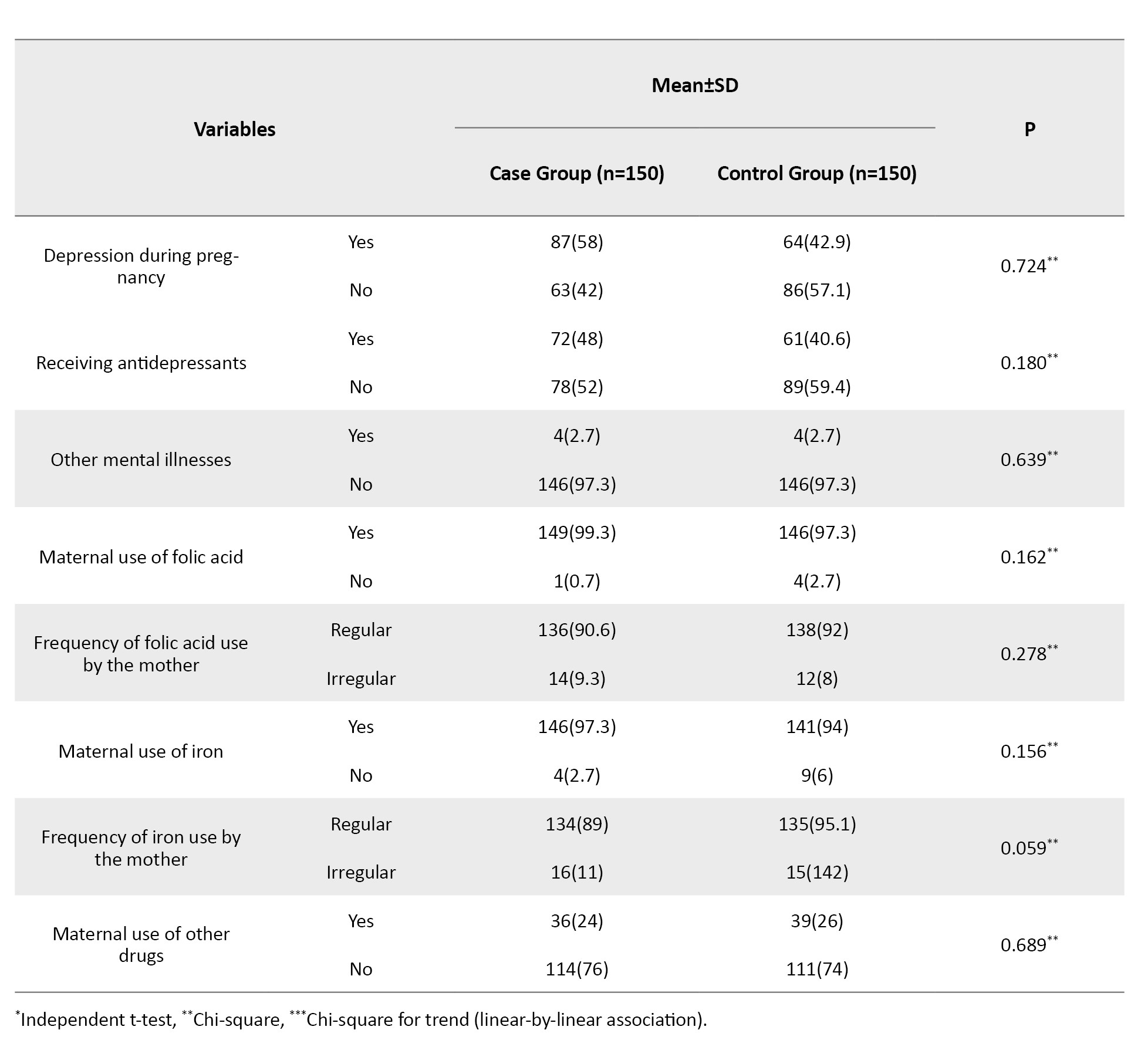

In total, 300 mothers with children aged under five years in two equal case and control groups were assessed. The mean age of mothers was 33.4±6.2 years in the case group and 30.3±5.1 years in the control group. Male children comprised 65.3% of the case group and 52% of the control group. Most mothers in both groups were housewives (86.7% in the case group and 76.0% in the control group), and the majority had an academic education (49.3% in the case group and 61.3% in the control group). Table 1 shows the socio-demographic, clinical, obstetric, and child characteristics of case and control groups and the results of the independent t-test, chi-square, and chi-square for trend (linear-by-linear association).

According to the multivariate logistic regression, secondary school education or lower (OR=0.81, 95% CI; 1.25%, 6.28%, P=0.012), history of child hospitalization (OR=3.02, 95% CI; 1.69%, 5.4%, P=0.001), delivery by emergency cesarean section (OR=2.47, 95% CI; 1.10%, 5.53%, P=0.028), history of infection during pregnancy (OR=5.0, 95% CI; 1.48%, 16.85%, P=0.009), and IUGR in the child (OR=3.7, 95% CI; 1.1%, 12.6%, P=0.038) were significantly associated with the increased risk of DD, whereas, breastfeeding the child (OR=0.49, 95% CI; 0.27%, 0.87%, P=0.016) and male gender of the child (OR=0.53, 95% CI; 0.32%, 0.89%, P=0.016) were significantly associated with the decreased risk of DD (Table 2).

Discussion

This case-control study investigated predictors of DD in children under five years in Tabriz, Iran. According to the results, male gender, emergency cesarean delivery, IUGR, mother’s educational level (secondary school or lower), child’s history of hospitalization, maternal infection during pregnancy, and breastfeeding were significant predictors of DD.

Children born via emergency cesarean delivery were about three times at higher risk of DD compared to those with vaginal delivery. Consistent with these results, the studies in Turkey [29] and Poland [30] found a significant association between cesarean delivery and DD. Proposed mechanisms include altered stress responses and changes in the gut microbiome affecting brain development [31-33]. A study in Australia indicated reduced cognitive outcomes among children with cesarean birth [34]. Emergency conditions before delivery increase the risk of brain injury and DD [35]. The risk of DD in boys was half the risk in girls, consistent with the results of a study in Norway [36], but against the results of studies from Taiwan, which reported higher DD rates among boys [37, 38]. These discrepancies suggest that gender differences in development may vary across populations, and further studies are warranted.

Our findings showed that the risk of DD in children born to mothers with a secondary school education or lower was about three times higher than that of mothers with a university education, which may be because mothers with a low educational level pay less attention to the developmental status of children and are less sensitive to this matter, causing negligence in the development progress of their children. Results from other studies have also confirmed a direct relationship between parents’ low education and DD in children [39, 40]. Given that educational attainment among women directly affects their independence, educated mothers are more likely to make independent decisions about their children’s health [41]. Maternal infection during pregnancy was found to lead to a fivefold increase in the risk of DD. Previous studies have also linked prenatal infections, particularly in the third trimester, with later cognitive impairments, reduced IQ, and problem-solving difficulties [42-44]. Intrauterine inflammation is also associated with long-term neurodevelopmental disorders such as cerebral palsy [45, 46], possibly due to cytokine-mediated effects on the fetal nervous system [43]. The child’s hospitalization history was another significant predictor. An Iranian study on 231 children showed similar results [47]. A cross-sectional study found that 26% of hospitalized children showed DD in at least one domain [48]. Since factors such as hypoxia, thyroid hormones, and environmental conditions (e.g. temperature, sound) can affect infant development—especially in neonatal intensive care units, where these factors may be hard to control—monitoring and managing them in neonatal wards is crucial.

It was found that IUGR in the child could increase the risk of DD by more than 3.5 times, consistent with prior evidence linking IUGR to cognitive, sensory, and motor deficits [49]. Structural brain changes, limited social skills, and lower anthropometric measures may contribute to these developmental differences [50]. Lack of breastfeeding was also significantly associated with the risk of DD, consistent with the results of previous studies [30, 51, 52]. Breastfed children often have higher IQ scores [53, 54], likely due to long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids supporting neural development, or enhanced emotional bonding between mother and child [55]. Promoting breastfeeding, therefore, may improve cognitive and developmental outcomes in the child.

Attention to the identified risk factors and designing preventive and interventional programs based on these factors can reduce DD incidence. Preventive care for pregnant women and early screening of children at high risk of DD are essential for better developmental outcomes. One of the strengths of this study is the involvement of a specialist in children’s growth and development for diagnosing DD, and matching the age of children in the two groups. However, there were some limitations, including the existence of potential biases such as social desirability bias and recall bias. Overall, based on the identified risk factors of DD in children under five years in Tabriz (emergency cesarean delivery, low maternal education, maternal infection, child hospitalization, IUGR, and lack of breastfeeding), targeted screening and early interventions are recommended. Healthcare providers should integrate these risk factors into routine child assessments and emphasize maternal education and breastfeeding promotion. Further longitudinal studies are recommended to clarify causal relationships and explore biological mechanisms, especially regarding gender and cesarean delivery.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran (Code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1400.679). Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all the participants before enrolment.

Funding

This study was funded by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran (Grant No.: 68310).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, review, editing, and final approval: All authors; Writing the initial draft: Somayeh Abdolalipour; Statistical analysis: Mojgan Mirghafourvand.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for their financial support and all women who participated in this study for their cooperation.

The Ages and Stages Questionnaires - Third Edition (ASQ-3) was also used in this study [27] to diagnose the DD in children. This instrument contains 19 items to screen for DD in children aged 4-60 months. It has five domains (communication, problem-solving, personal-social skills, fine motor, and gross motor), each with six items. Parents can answer the questions with “yes, (10 points)”, “sometimes, (5 points)”, or “not yet (0 points)”. The total score for each domain ranges from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate better performance in that domain. The scores for each domain are summed up to obtain the questionnaire’s total score, which is then plotted against the cutoff point to determine whether the child is on schedule, needs monitoring, or requires further assessment. A score above the cutoff point indicates that the child’s development in that domain is on schedule. A score equal to or below the cutoff point suggests possible risk of DD and the need for further evaluation or intervention. The overall developmental status is therefore coded as a binary variable: 1=DD and 0=normal development [27]. The adaptation and standardization of the Persian version were conducted in Iran by Vameghi et al., who demonstrated the test’s ability to detect DD at >96% [28].

After providing comprehensive information about the study objectives, benefits, results, and confidentiality of the information during a face-to-face visit with the participants, their informed consent was obtained. The questionnaires were then completed through interviews with mothers, ensuring complete responses from all participants. The collected data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 24. The dependent variable was developmental status (1=case with DD, 0=control without DD), and the independent variables were socio-demographic, clinical, obstetric, and child characteristics. To determine the relationship of these characteristics with DD, an independent t-test, chi-square test, and Chi-square for trend (linear-by-linear association) were used in bivariate analysis. Multivariable logistic regression using the enter method in a single-step analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of DD.

Results

In total, 300 mothers with children aged under five years in two equal case and control groups were assessed. The mean age of mothers was 33.4±6.2 years in the case group and 30.3±5.1 years in the control group. Male children comprised 65.3% of the case group and 52% of the control group. Most mothers in both groups were housewives (86.7% in the case group and 76.0% in the control group), and the majority had an academic education (49.3% in the case group and 61.3% in the control group). Table 1 shows the socio-demographic, clinical, obstetric, and child characteristics of case and control groups and the results of the independent t-test, chi-square, and chi-square for trend (linear-by-linear association).

According to the multivariate logistic regression, secondary school education or lower (OR=0.81, 95% CI; 1.25%, 6.28%, P=0.012), history of child hospitalization (OR=3.02, 95% CI; 1.69%, 5.4%, P=0.001), delivery by emergency cesarean section (OR=2.47, 95% CI; 1.10%, 5.53%, P=0.028), history of infection during pregnancy (OR=5.0, 95% CI; 1.48%, 16.85%, P=0.009), and IUGR in the child (OR=3.7, 95% CI; 1.1%, 12.6%, P=0.038) were significantly associated with the increased risk of DD, whereas, breastfeeding the child (OR=0.49, 95% CI; 0.27%, 0.87%, P=0.016) and male gender of the child (OR=0.53, 95% CI; 0.32%, 0.89%, P=0.016) were significantly associated with the decreased risk of DD (Table 2).

Discussion

This case-control study investigated predictors of DD in children under five years in Tabriz, Iran. According to the results, male gender, emergency cesarean delivery, IUGR, mother’s educational level (secondary school or lower), child’s history of hospitalization, maternal infection during pregnancy, and breastfeeding were significant predictors of DD.

Children born via emergency cesarean delivery were about three times at higher risk of DD compared to those with vaginal delivery. Consistent with these results, the studies in Turkey [29] and Poland [30] found a significant association between cesarean delivery and DD. Proposed mechanisms include altered stress responses and changes in the gut microbiome affecting brain development [31-33]. A study in Australia indicated reduced cognitive outcomes among children with cesarean birth [34]. Emergency conditions before delivery increase the risk of brain injury and DD [35]. The risk of DD in boys was half the risk in girls, consistent with the results of a study in Norway [36], but against the results of studies from Taiwan, which reported higher DD rates among boys [37, 38]. These discrepancies suggest that gender differences in development may vary across populations, and further studies are warranted.

Our findings showed that the risk of DD in children born to mothers with a secondary school education or lower was about three times higher than that of mothers with a university education, which may be because mothers with a low educational level pay less attention to the developmental status of children and are less sensitive to this matter, causing negligence in the development progress of their children. Results from other studies have also confirmed a direct relationship between parents’ low education and DD in children [39, 40]. Given that educational attainment among women directly affects their independence, educated mothers are more likely to make independent decisions about their children’s health [41]. Maternal infection during pregnancy was found to lead to a fivefold increase in the risk of DD. Previous studies have also linked prenatal infections, particularly in the third trimester, with later cognitive impairments, reduced IQ, and problem-solving difficulties [42-44]. Intrauterine inflammation is also associated with long-term neurodevelopmental disorders such as cerebral palsy [45, 46], possibly due to cytokine-mediated effects on the fetal nervous system [43]. The child’s hospitalization history was another significant predictor. An Iranian study on 231 children showed similar results [47]. A cross-sectional study found that 26% of hospitalized children showed DD in at least one domain [48]. Since factors such as hypoxia, thyroid hormones, and environmental conditions (e.g. temperature, sound) can affect infant development—especially in neonatal intensive care units, where these factors may be hard to control—monitoring and managing them in neonatal wards is crucial.

It was found that IUGR in the child could increase the risk of DD by more than 3.5 times, consistent with prior evidence linking IUGR to cognitive, sensory, and motor deficits [49]. Structural brain changes, limited social skills, and lower anthropometric measures may contribute to these developmental differences [50]. Lack of breastfeeding was also significantly associated with the risk of DD, consistent with the results of previous studies [30, 51, 52]. Breastfed children often have higher IQ scores [53, 54], likely due to long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids supporting neural development, or enhanced emotional bonding between mother and child [55]. Promoting breastfeeding, therefore, may improve cognitive and developmental outcomes in the child.

Attention to the identified risk factors and designing preventive and interventional programs based on these factors can reduce DD incidence. Preventive care for pregnant women and early screening of children at high risk of DD are essential for better developmental outcomes. One of the strengths of this study is the involvement of a specialist in children’s growth and development for diagnosing DD, and matching the age of children in the two groups. However, there were some limitations, including the existence of potential biases such as social desirability bias and recall bias. Overall, based on the identified risk factors of DD in children under five years in Tabriz (emergency cesarean delivery, low maternal education, maternal infection, child hospitalization, IUGR, and lack of breastfeeding), targeted screening and early interventions are recommended. Healthcare providers should integrate these risk factors into routine child assessments and emphasize maternal education and breastfeeding promotion. Further longitudinal studies are recommended to clarify causal relationships and explore biological mechanisms, especially regarding gender and cesarean delivery.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran (Code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1400.679). Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all the participants before enrolment.

Funding

This study was funded by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran (Grant No.: 68310).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, review, editing, and final approval: All authors; Writing the initial draft: Somayeh Abdolalipour; Statistical analysis: Mojgan Mirghafourvand.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for their financial support and all women who participated in this study for their cooperation.

References

- Glidden LM, Abbeduto LE, McIntyre LL, Tassé MJ. APA handbook of intellectual and developmental disabilities: Foundations, Vol. 1. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2021. [DOI:10.1037/0000194-000]

- Khan I, Leventhal BL. Developmental Delay. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2025. [PMID]

- Wondmagegn T, Girma B, Habtemariam Y. Prevalence and determinants of developmental delay among children in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2024; 12:1301524. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1301524] [PMID]

- Alijanzadeh M, RajabiMajd N, RezaeiNiaraki M, Griffiths MD, Alimoradi Z. Prevalence and socio-economic determinants of growth and developmental delays among Iranian children aged under five years: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2024; 24(1):412.[DOI:10.1186/s12887-024-04880-2] [PMID]

- Andriana A. Early Intervention Programs for Developmental Delays in Children. ARC J Pediatr. 2025; 10(3); 7-12. [DOI:10.20431/2455-5711.1003002]

- Bishwokarma A, Shrestha D, Bhujel K, Chand N, Adhikari L, Kaphle M, et al. Developmental delay and its associated factors among children under five years in urban slums of Nepal. Plos One. 2022; 17(2):e0263105. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0263105] [PMID]

- Choo YY, Agarwal P, How CH, Yeleswarapu SP. Developmental delay: Identification and management at primary care level. Singapore Med J. 2019; 60(3):119-23. [DOI:10.11622/smedj.2019025] [PMID]

- Bélanger SA, Caron J. Evaluation of the child with global developmental delay and intellectual disability. Paediatr Child Health. 2018; 23(6):403-19. [DOI:10.1093/pch/pxy093] [PMID]

- Wang L, Liang W, Zhang S, Jonsson L, Li M, Yu C, et al. Are infant/toddler developmental delays a problem across rural China?. J Comp Econ. 2019; 47(2):458-69. [DOI:10.1016/j.jce.2019.02.003]

- Roostin E. Family influence on the development of children. J Prim Educ. 2018; 2(1):1-2. [DOI:10.22460/pej.v1i1.654]

- Nīmante D. Family and Environmental Factors Influencing Child Development. Hum Technol Qual Educ. 2023; 7:103-16. [DOI:10.22364/htqe.2023.07]

- Gladstone M, Oliver C, Van den Broek N. Survival, morbidity, growth and developmental delay for babies born preterm in low and middle income countries - a systematic review of outcomes measured. Plos One. 2015; 10(3):e0120566. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0120566] [PMID]

- Howe TH, Sheu CF, Hsu YW, Wang TN, Wang LW. Predicting neurodevelopmental outcomes at preschool age for children with very low birth weight. Res Dev Disabil. 2016; 48:231-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.003] [PMID]

- Oudgenoeg-Paz O, Mulder H, Jongmans MJ, van der Ham IJ, Van der Stigchel S. The link between motor and cognitive development in children born preterm and/or with low birth weight: A review of current evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017; 80:382-93. [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.06.009] [PMID]

- Kerstjens JM, de Winter AF, Sollie KM, Bocca-Tjeertes IF, Potijk MR, Reijneveld SA, et al. Maternal and pregnancy-related factors associated with developmental delay in moderately preterm-born children. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 121(4):727-33. [DOI:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182860c52] [PMID]

- Hee Chung E, Chou J, Brown KA. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants: A recent literature review. Transl Pediatr. 2020; 9(Suppl 1):S3-S8. [DOI:10.21037/tp.2019.09.10] [PMID]

- Jahnen L, Konrad K, Dahmen B, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Firk C. [The impact of adolecent motherhood on child development in preschool children- identification of maternal risk factors (German)]. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2020; 48(4):277-88. [DOI:10.1024/1422-4917/a000728] [PMID]

- Koutra K, Chatzi L, Bagkeris M, Vassilaki M, Bitsios P, Kogevinas M. Antenatal and postnatal maternal mental health as determinants of infant neurodevelopment at 18 months of age in a mother-child cohort (Rhea Study) in Crete, Greece. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013; 48(8):1335-45. [DOI:10.1007/s00127-012-0636-0] [PMID]

- Jensen SK, Dumontheil I, Barker ED. Developmental inter-relations between early maternal depression, contextual risks, and interpersonal stress, and their effect on later child cognitive functioning. Depress Anxiety. 2014; 31(7):599-607. [DOI:10.1002/da.22147] [PMID]

- Saros L, Lind A, Setänen S, Tertti K, Koivuniemi E, Ahtola A, et al. Maternal obesity, gestational diabetes mellitus, and diet in association with neurodevelopment of 2-year-old children. Pediatr Res. 2023 ; 94(1):280-9. [DOI:10.1038/s41390-022-02455-4] [PMID]

- Xiang AH, Wang X, Martinez MP, Getahun D, Page KA, Buchanan TA, et al. Maternal Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1 Diabetes, and Type 2 Diabetes During Pregnancy and Risk of ADHD in Offspring. Diabetes Care. 2018; 41(12):2502-8. [DOI:10.2337/dc18-0733] [PMID]

- Nomura Y, Marks DJ, Grossman B, Yoon M, Loudon H, Stone J. Exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus and low socioeconomic status: effects on neurocognitive development and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):337-43. [DOI:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.784] [PMID]

- Chen J, Zhu J, Huang X, Zhao S, Xiang H, Zhou P, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism with negative for thyroid peroxidase antibodies in pregnancy: Intellectual development of offspring. Thyroid. 2022; 32(4):449-58. [DOI:10.1089/thy.2021.0374] [PMID]

- Amouzegar A, Pearce EN, Mehran L, Lazarus J, Takyar M, Azizi F. TPO antibody in euthyroid pregnant women and cognitive ability in the offspring: A focused review. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022; 45(2):425-31. [DOI:10.1007/s40618-021-01664-8] [PMID]

- No Author. Random.org [internet]. 2025 [Updated 6 January 2026]. Available from: [Link]

- Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007; 165(6):710-8. [DOI:10.1093/aje/kwk052] [PMID]

- Squires J, Bricker DD, Twombly E. Ages & stages questionnaires. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 2009. [Link]

- Vameghi R, Sajedi F, Mojembari AK, Habiollahi A, Lornezhad HR, Delavar B. Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validation and Standardization of Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) in Iranian Children. Iran J Public Health. 2013; 42(5):522-8. [PMID]

- Demirci A, Kartal M. Sociocultural risk factors for developmental delay in children aged 3-60 months: A nested case-control study. Eur J pediatr. 2018; 177:691-7. [DOI:10.1007/s00431-018-3109-y] [PMID]

- Drozd-Dąbrowska M, Trusewicz R, Ganczak M. Selected risk factors of developmental delay in Polish infants: A case-control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018; 15(12):2715. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph15122715] [PMID]

- Bäckhed F, Roswall J, Peng Y, Feng Q, Jia H, Kovatcheva-Datchary P. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015; 17(5):690-703. [DOI:10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004] [PMID]

- Hoban AE, Stilling RM, Ryan FJ, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Claesson MJ. Regulation of prefrontal cortex myelination by the microbiota. Transl Psychiatry. 2016; 6(4):e774. [DOI:10.1038/tp.2016.42] [PMID]

- Gars A, Ronczkowski NM, Chassaing B, Castillo-Ruiz A, Forger NG. First encounters: Effects of the microbiota on neonatal brain development. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021; 15:682505. [DOI:10.3389/fncel.2021.682505] [PMID]

- Polidano C, Zhu A, Bornstein JC. The relation between cesarean birth and child cognitive development. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1):11483. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-10831-y] [PMID]

- Bajalan Z, Alimoradi Z. Risk factors of developmental delay among infants aged 6-18 months. Early Child Dev Care. 2020; 190(11):1691-9. [DOI:10.1080/03004430.2018.1547714]

- Richter J, Janson H. A validation study of the Norwegian version of the ages and stages questionnaires. Acta Paediatrica. 2007; 96(5):748-52. [DOI:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00246.x] [PMID]

- Lai DC, Tseng YC, Guo HR. Characteristics of young children with developmental delays and their trends over 14 years in Taiwan: A population-based nationwide study. BMJ Open. 2018; 8(5):e020994. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020994] [PMID]

- Tseng YC, Lai DC, Guo HR. Gender and geographic differences in the prevalence of reportable childhood speech and language disability in Taiwan. Res Dev Disabil. 2015; 40:11-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.01.009] [PMID]

- Kapci EG, Kucuker S, Uslu RI. How applicable are ages and stages questionnaires for use with Turkish children? Topics Early Child Spec Educ. 2010; 30(3):176-88. [DOI:10.1177/0271121410373149]

- Hosseinzadeh Z, Bakhshi E, Jashni Motlagh A, Biglarian A. Application of quantile regression to identify of risk factors in infant’s growth parameters. Razi J Medi Sci. 2018; 24(165):85-95. [Link]

- Dagvadorj A, Ganbaatar D, Balogun OO, Yonemoto N, Bavuusuren B, Takehara K. Maternal socio-demographic and psychological predictors for risk of developmental delays among young children in Mongolia. BMC Pediatr. 2018; 18:1-8. [DOI:10.1186/s12887-018-1017-y]

- Kwok J, Hall HA, Murray AL, Lombardo MV, Auyeung B. Maternal infections during pregnancy and child cognitive outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022; 22(1):848. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-022-05188-8] [PMID]

- Lee YH, Papandonatos GD, Savitz DA, Heindel WC, Buka SL. Effects of prenatal bacterial infection on cognitive performance in early childhood. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2020; 34(1):70-9. [DOI:10.1111/ppe.12603] [PMID]

- Khorrami Z, Namdar A. [Development status among one-year-old children referring to urban health centers of jahrom: An assessment based on ages and stages questionnaires (Persian)]. Community Health. 2018; 5(2):141-50. [Link]

- Ganguli S, Chavali PL. Intrauterine viral infections: Impact of inflammation on fetal neurodevelopment. Front Neurosci. 2021; 15:771557. [DOI:10.3389/fnins.2021.771557] [PMID]

- Wang T, Mohammadzadeh P, Jepsen JR, Thorsen J, Rosenberg JB, Lemvigh CK, et al. Maternal inflammatory proteins in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental disorders at age 10 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2025; 82(5):514-25. [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.0122] [PMID]

- Moradipourghavam Z, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Barati M, Doosti-Irani A, Nouri S. Associated factors with developmental delay of under 5 year old children in Hamadan, Iran: A case-control study. J EducCommunity Health. 2020; 7(4):263-73. [Link]

- Dorre F, Fattahi Bayat G. Evaluation of children’s development (4-60mo) with history of NICU admission based on ASQ in Amir kabir Hospital, Arak. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci. 2011; 11(2):143-50. [Link]

- Sacchi C, De Carli P, Mento G, Farroni T, Visentin S, Simonelli A. Socio-emotional and cognitive development in intrauterine growth restricted (IUGR) and typical development infants: Early interactive patterns and underlying neural correlates. Rationale and methods of the study. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018; 12:315. [DOI:10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00315] [PMID]

- Rocha PRH, Saraiva MDCP, Barbieri MA, Ferraro AA, Bettiol H. Association of preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction with childhood motor development: Brisa cohort, Brazil. Infant Behav Dev. 2020; 58:101429. [DOI:10.1016/j.infbeh.2020.101429] [PMID]

- Lawrence RM. Host-resistance factors and immunologic significance of human milk. Breastfeeding. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2022. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-323-68013-4.00005-5]

- Rumalean H, Tursinawati Y, Ramaningrum G. Giving exclusive breastfeeding and maternal gestational age affects the developmental delay of children aged 3-36 months. J Info Kesehatan. 2020; (1):1-8. [DOI: 10.31965/infokes.Vol18.Iss1.302]

- Radfar M, Jafari N, Karimi KM, Taslimi TN, Askary KR, Yazdi L. [ of predisposing factors for developmental delay of pre-term infants in the first year of life (Persian)]. Tehran Univ Med J. 2021; 78(12):843-52. [Link]

- Lovcevic I. Associations of breastfeeding duration and cognitive development from childhood to middle adolescence. Acta Paediatr. 2023; 112(8):1696-705. [DOI:10.1111/apa.16837] [PMID]

- Kim KM, Choi JW. Associations between breastfeeding and cognitive function in children from early childhood to school age: A prospective birth cohort study. Int Breastfeed J. 2020; 15(1):83.[DOI:10.1186/s13006-020-00326-4] [PMID]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2024/11/28 | Accepted: 2025/05/6 | Published: 2026/01/11

Received: 2024/11/28 | Accepted: 2025/05/6 | Published: 2026/01/11

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |