Tue, Dec 2, 2025

Volume 35, Issue 1 (1-2025)

JHNM 2025, 35(1): 81-89 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Laamiri F Z, Barich F, Chafik K, Bouzid J, Chahboune M, Elkhoudri N, et al . Study of the Clinical Learning Challenges of Moroccan Nursing Students. JHNM 2025; 35 (1) :81-89

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2059-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2059-en.html

Fatima Zahra Laamiri *1

, Fatima Barich2

, Fatima Barich2

, Kawtar Chafik2

, Kawtar Chafik2

, Jawad Bouzid3

, Jawad Bouzid3

, Mohamed Chahboune3

, Mohamed Chahboune3

, Noureddine Elkhoudri3

, Noureddine Elkhoudri3

, Saad El madani3

, Saad El madani3

, Amina Barkat4

, Amina Barkat4

, Fatima Barich2

, Fatima Barich2

, Kawtar Chafik2

, Kawtar Chafik2

, Jawad Bouzid3

, Jawad Bouzid3

, Mohamed Chahboune3

, Mohamed Chahboune3

, Noureddine Elkhoudri3

, Noureddine Elkhoudri3

, Saad El madani3

, Saad El madani3

, Amina Barkat4

, Amina Barkat4

1- Professor, Laboratory of Sciences and Health Technologies, Higher Institute of Health Sciences of Settat, Hassan First University, Settat, Morocco. , Fatimazahra.laamiri@uhp.ac.ma

2- Professor, Higher Institutes of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques, Rabat, Morocco.

3- Professor, Laboratory of Sciences and Health Technologies, Higher Institute of Health Sciences of Settat, Hassan First University, Settat, Morocco.

4- Professor, Health and Nutrition Research Team of the Mother-Child Couple, Faculty of Medicine, Mohammed V University, Rabat, Morocco.

2- Professor, Higher Institutes of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques, Rabat, Morocco.

3- Professor, Laboratory of Sciences and Health Technologies, Higher Institute of Health Sciences of Settat, Hassan First University, Settat, Morocco.

4- Professor, Health and Nutrition Research Team of the Mother-Child Couple, Faculty of Medicine, Mohammed V University, Rabat, Morocco.

Full-Text [PDF 476 kb]

(459 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (636 Views)

Full-Text: (365 Views)

Introduction

In recent decades, nursing education has undergone reforms aligned with the Bologna principles, aimed at addressing issues such as mobility and employment of graduates by standardizing university qualifications [1]. The university curriculums allow students to learn the concepts essential for their professional practice, while facilitating adaptation to evolving contexts and potential transitions to other professional sectors. Morocco has adopted a training model for health education, which includes the reorganization of curriculums at institutions such as the Higher Institute of Health Sciences in Settat and Higher Institutes of Nursing Professions and Health Technique [2]. This paradigm shift was initiated by a decree in 1993 establishing educational institutes for health careers. Education in health sciences involves a combination of theoretical education and practical clinical learning, often referred to as internship or learning in a clinical setting. This hands-on experience exposes students to diverse situations and practices, challenging them to apply academic knowledge in real-world scenarios [3-5]. The primary goal of the internship is to enable learners to apply their acquired knowledge in practice, fostering authentic and complex learning experiences [6-8].

The internship program receives less time compared to academic education, and the reduction in clinical placement days limits learning opportunities for students. This reduction is attributed to guidelines mandating internship modules to span between 80 and 160 hours, which is a significant time gap in education at the national level, with African students in health science experiencing a 1.5-year lag compared to their European counterparts. Consequently, African students often serve as passive observers, lacking opportunities to apply defined learning objectives.

Critical care wards, such as emergency departments, intensive care units, and specialized units, offer rich learning environments [9]. However, the limited exposure may hinder students from identifying various clinical situations and developing essential skills in patient management and technical health practice. By investing in research and fostering collaboration between academic institutions, healthcare organizations, and frontline professionals, we can make strides towards higher-quality and more accessible healthcare for all citizens. This study aims to investigate the constraints that affect clinical learning in nursing students in Morocco.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive study was conducted between September and December 2021 at two academic institutions (the Higher Institute of Health Sciences in Settat and the Higher Institute of Nursing and Health Techniques in Rabat). These institutions were selected due to having a wide range of specialties in the field of nursing science.

For sampling, we employed a purposive sampling method, as a non-probabilistic approach. As a result, the sample size was not predetermined. A total of 400 questionnaires were distributed to nursing students from the two institutions who met the inclusion criteria and were studying at the level of interest. Out of 400, 388 students agreed to participate and returned completed questionnaires, representing a high response rate of 97%. The study included students currently enrolled in nursing programs who had completed one or more clinical internships. Students who did not declare informed consent were not included in the study.

A questionnaire was developed to explore the constraints and challenges encountered by students during their clinical education. The questionnaire had 37 multiple-choice, open-ended, and semi-open-ended questions to assess the following five domains: a) Sociodemographic information (such as age, gender, place of residence, institution name, year of education, field of study, option of training, as well as reasons for choosing the field of study), b) Factors related to students, focusing on their appreciation of the internship, the activities offered in the clinical setting, the transfer of theoretical and practical knowledge taught in the academic setting, satisfaction with clinical training, and reasons for their interest; c) Students’ relationship with the healthcare team and patients during their clinical education: This includes understanding how students interact with the healthcare team and patients, which is crucial for their professional development; d) Factors related to learning in the clinical setting, covering the planning of informational sessions before the internship, the quality of reception by healthcare team, the understanding of the student’s role from the first day, the learning situations proposed by supervisors, the availability and use of materials, the student’s appreciation of the time dedicated to the internship, site selection, and the achievement of objectives; e) The supervision, addressing the presence and guidance of a supervisor during learning activities in the clinical environment, as well as the ongoing assessment of students throughout their internship. The students were given a time of 30 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

To assess the ability of the instrument to represent the constraints of clinical education in nursing students, its content validity was determined. In this regard, the opinions of researchers and healthcare professionals with expertise in the related field were used. The reliability of the instrument was assessed based on internal consistency and reproducibility. The reproducibility was determined by test re-test method [10, 11]. In this regard, 15 participants completed the questionnaire at two different times with a three-week interval. The findings demonstrated an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.85, indicating the questionnaire’s strong test re-test reliability. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s α coefficient, which yielded a value of 0.80, reflecting substantial internal consistency across the items and confirming their relevance and alignment with the measured constructs.

The collected data were analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software, version 20. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the normality of data distribution for the quantitative variables. This test revealed a normal distribution for the variable “student age” and was expressed in Mean±SD. Qualitative variables were expressed in frequency and percentage.

Results

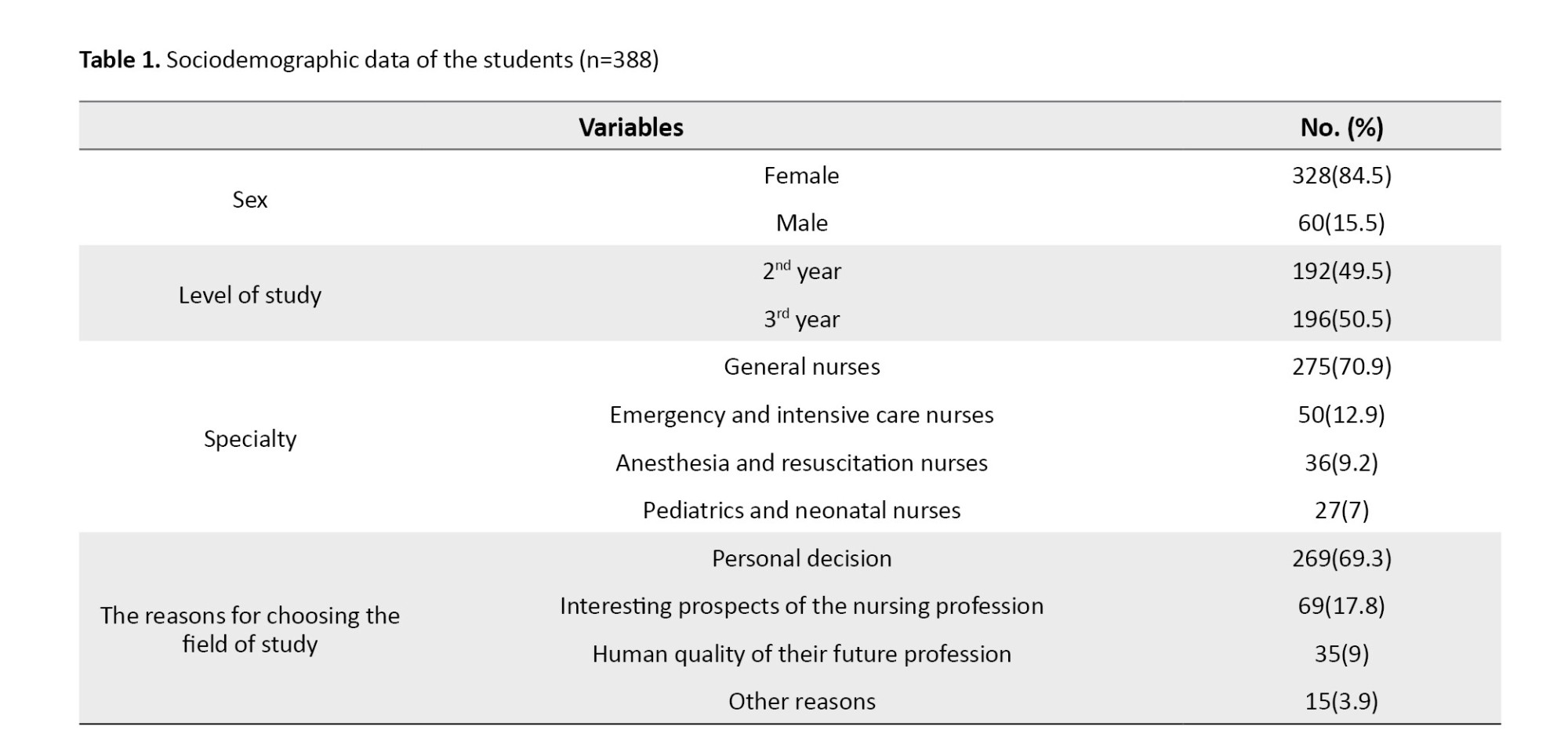

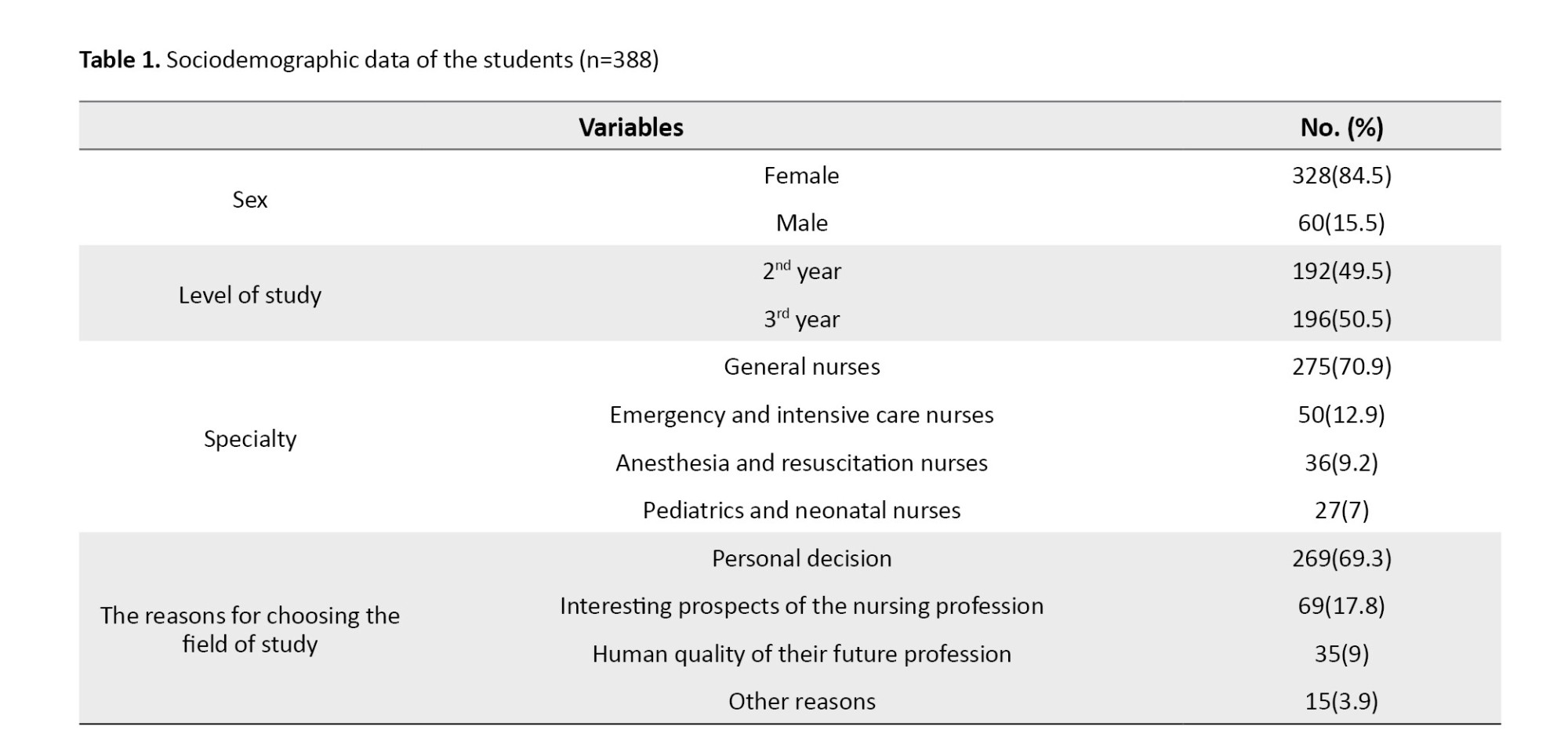

Analysis of the sociodemographic data (Table 1) revealed that most of the students were female (84.5%). The mean age of the students was 20.42±1.37 years, ranging from 19 to 26 years. In terms of specialty, there were four types of participants: General nurses (70.9%), emergency and intensive care nurses (12.9%), anesthesia and resuscitation nurses (9.2%), and pediatrics and neonatal nurses (7%). The majority of the students (69.3%) reported that they chose their field of study based on a personal decision, while for 17.8% it was for the interesting prospects of the nursing profession, and for 12.98% it was because of the human quality of their future profession.

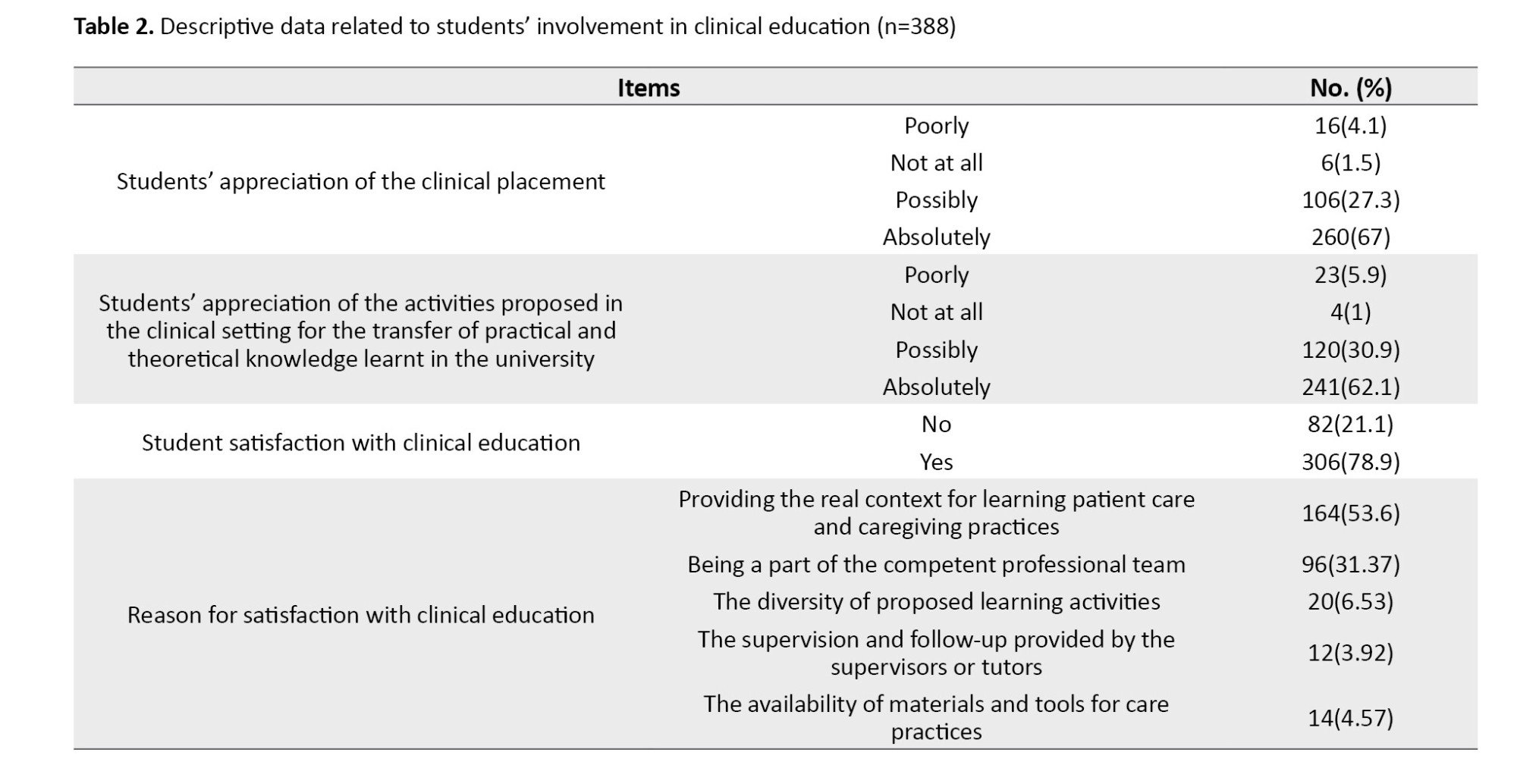

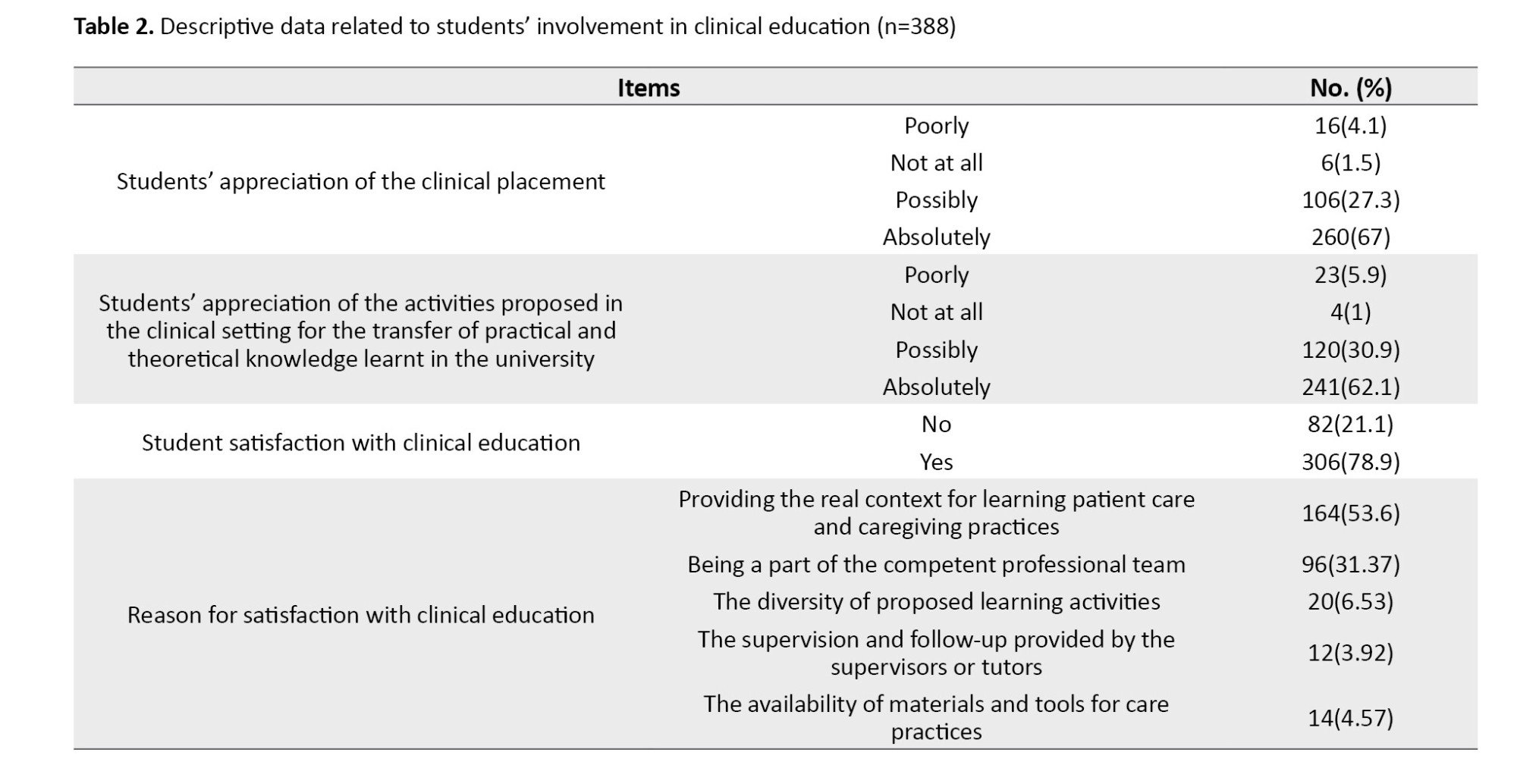

Regarding the data related to students’ involvement in clinical education (Table 2), it was found that more than half of the participants perceived that the clinical setting was effective for clinical learning (67%) and the training activities helped transfer theoretical knowledge (62.1%). Many appreciated the training for its authentic learning context (53.27%), professional team integration (31.37%), or other reasons (15.36%). However, 68.3% were dissatisfied with their clinical supervision, while 15.2% were satisfied or indifferent.

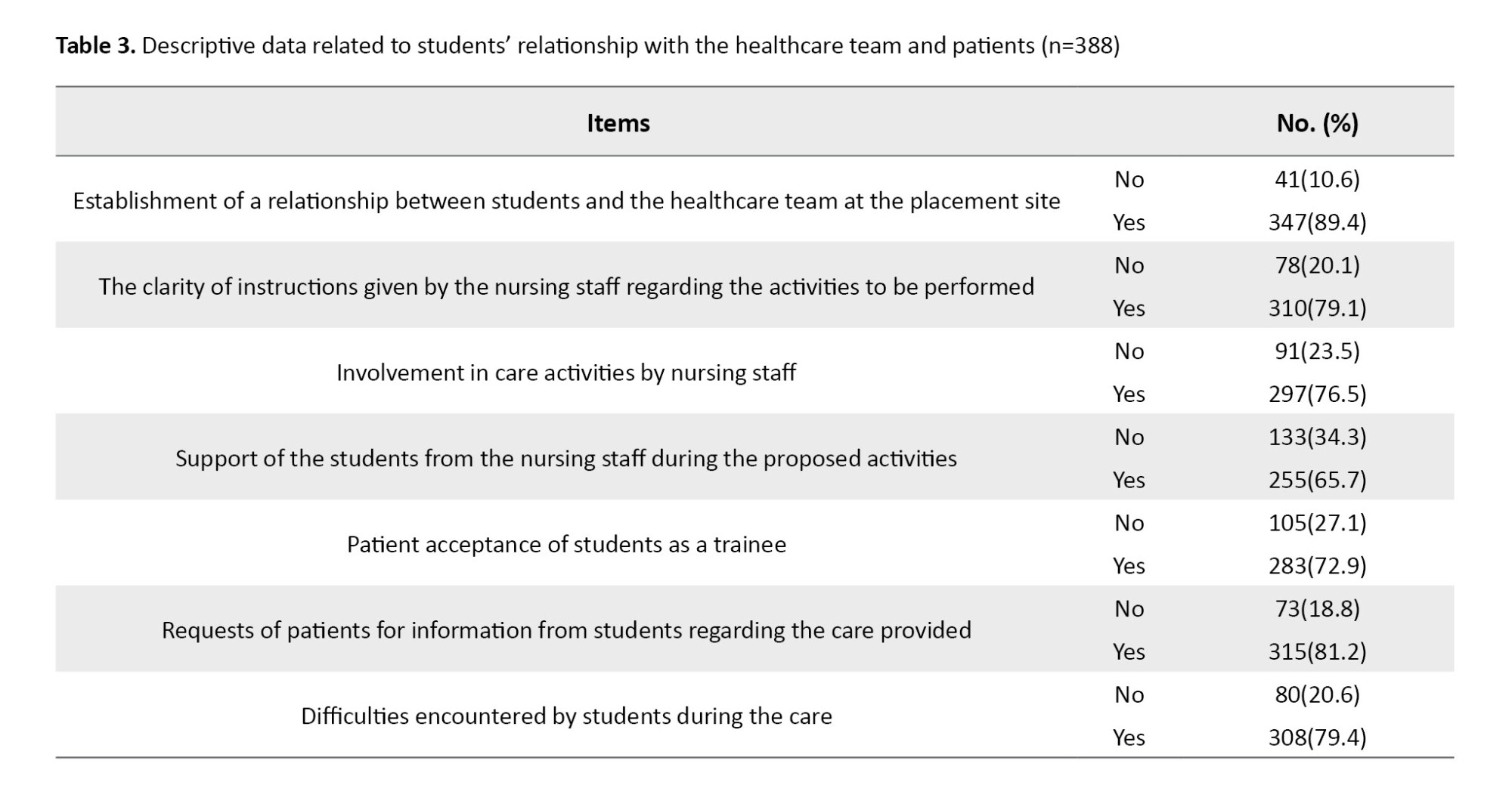

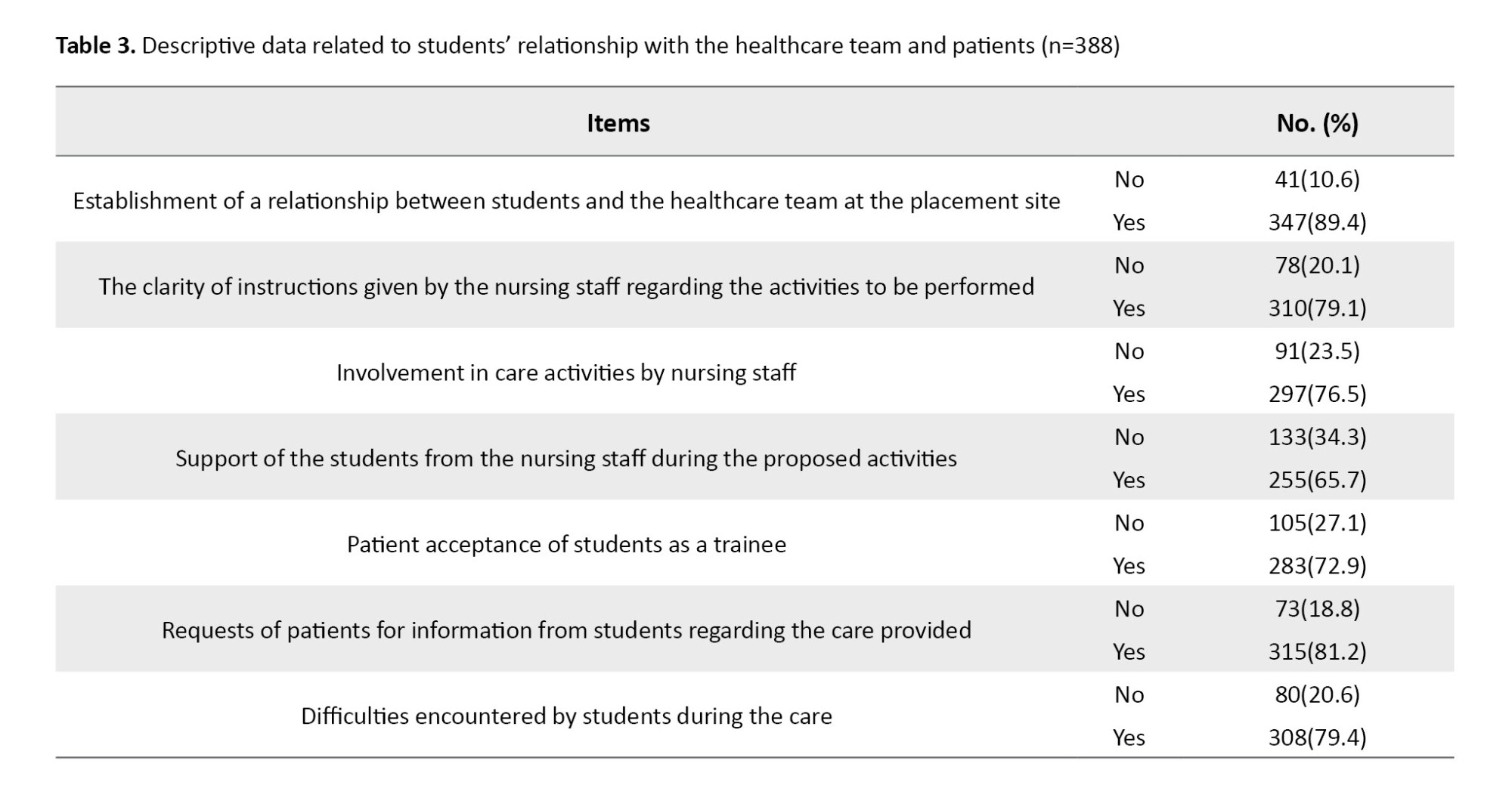

Regarding the data related to students’ relationship with the healthcare team (Table 3), it was found that most of the students had a positive relationship with healthcare team members (90%), received clear instructions (80%), were involved in care activities (76.5%), and perceived the support from the nursing staff (65.7%). Students were generally accepted by patients (72.9%), although some faced difficulties such as language barriers and patient distrust (79.4%). Almost all students (96.4%) reported that participating in care activities was crucial for skill development, and 88.9% felt capable of transferring theoretical knowledge to clinical settings.

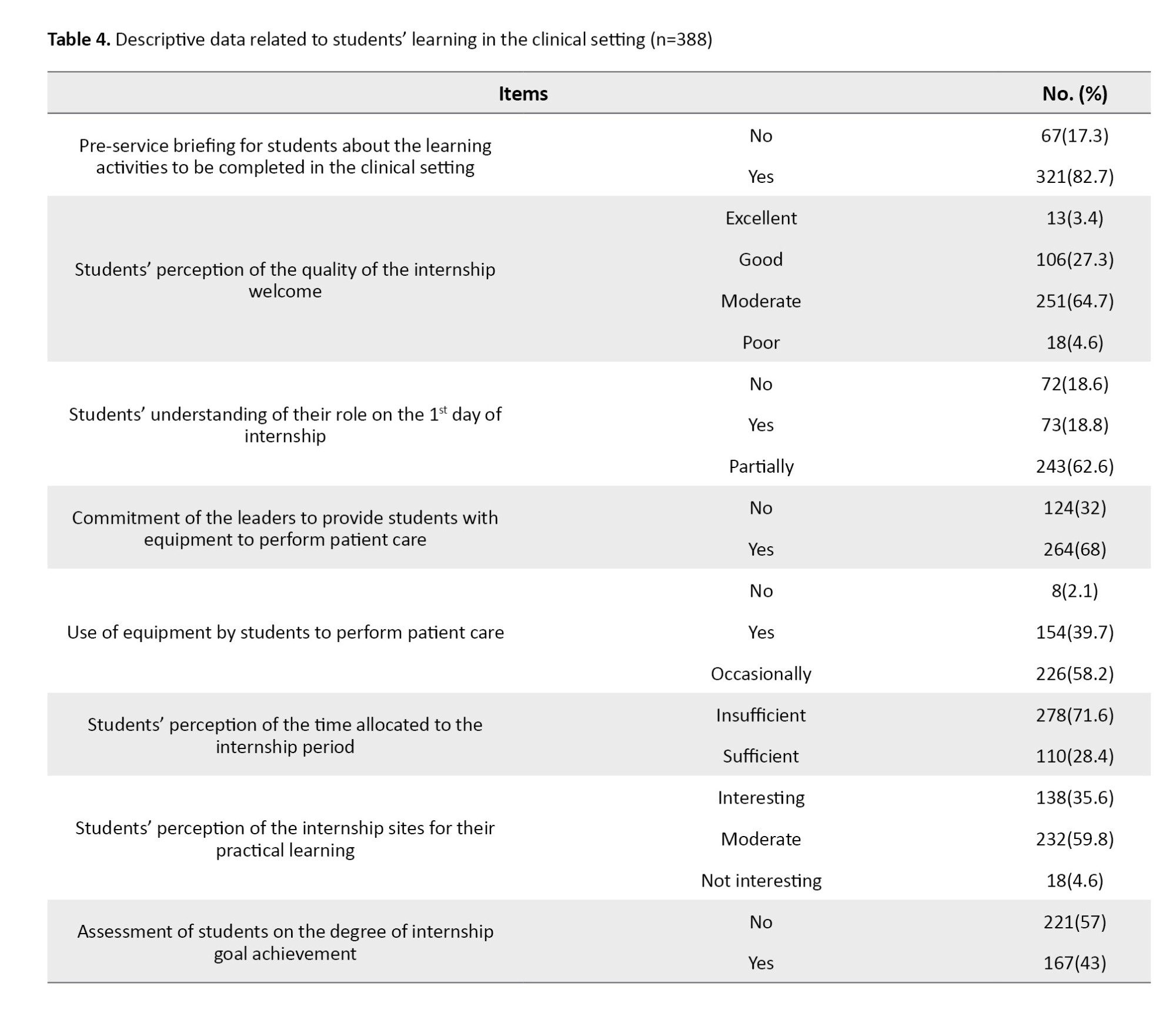

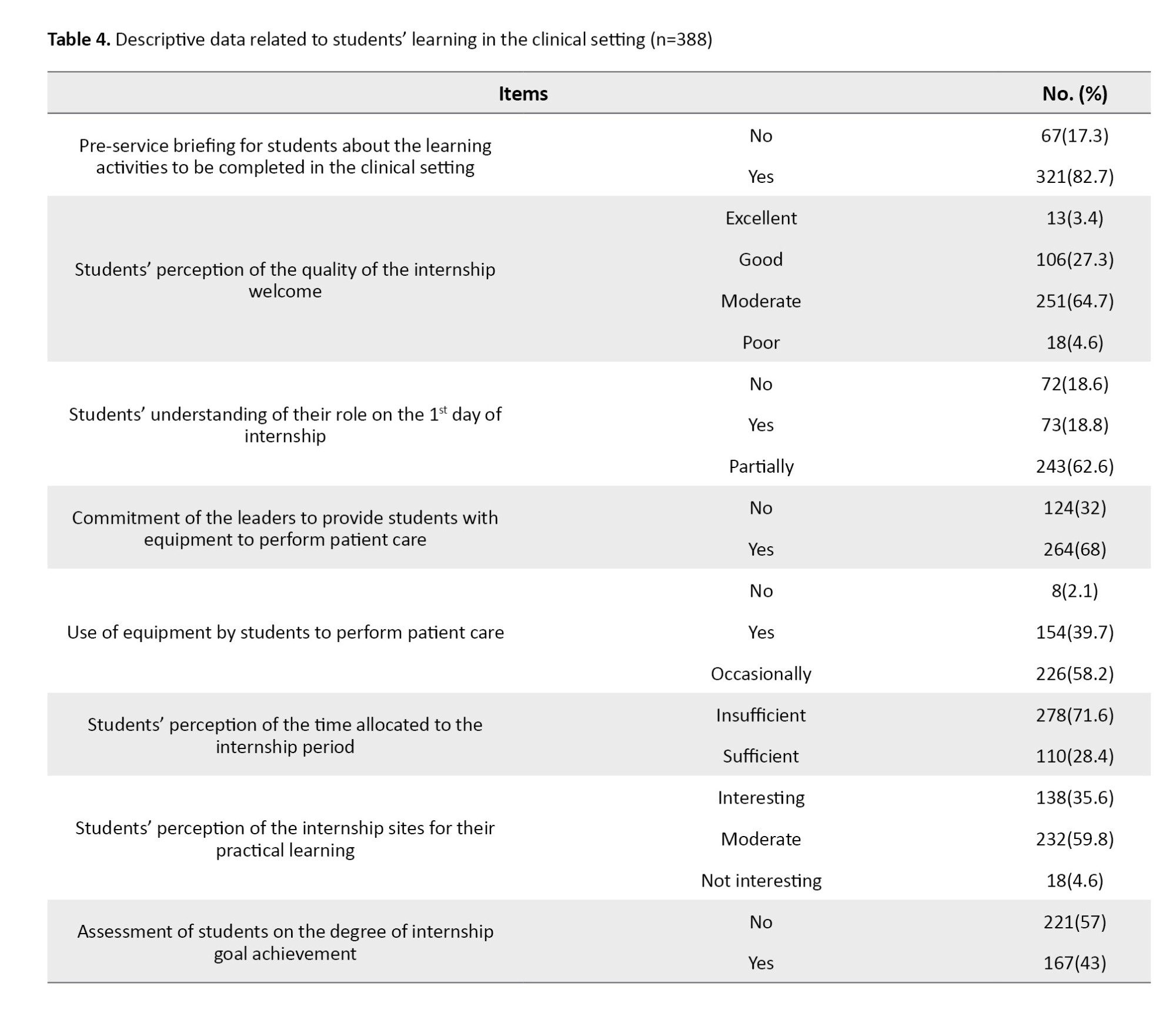

Regarding the data related to learning in clinical settings (Table 4), it was found that 82.7% of students had received a pre-service briefing from different channels, specifically from the program coordinator (48.8%), during a session organized by the educational staff (24.7%), or from the internship guide (15.7%). According to 64.7% of students, the quality of internship welcome was moderate, and 62.6% had a partial understanding of their role during the first days of the internship. Also, 68% stated that the nursing leaders had provided them with the necessary equipment for patient care, and 58.2% mentioned that they occasionally used the provided equipment for their internship activities. Additionally, 71.6% believed that the time dedicated to the internship was insufficient, and almost 60% reported that the internship sites selected for their practical learning were at a moderate level. More than half of the students (57%) reported unmet internship goals. Almost all students (92%) reported a progression in learning when participating in care activities during semesters or the academic year. However, nearly one-third of the students reported not being evaluated during their internship, and the majority (82.2%) encountered constraints in the clinical setting.

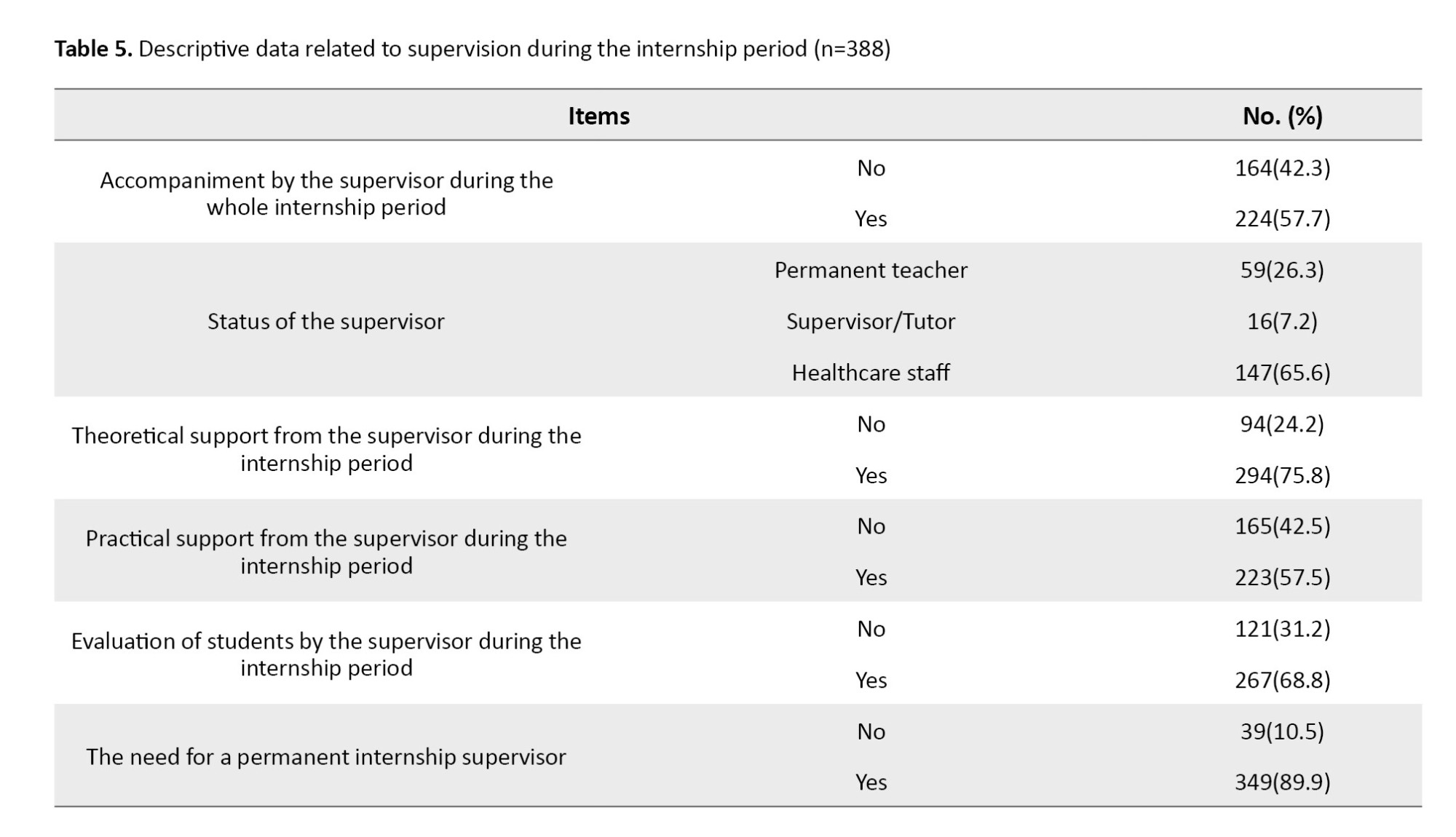

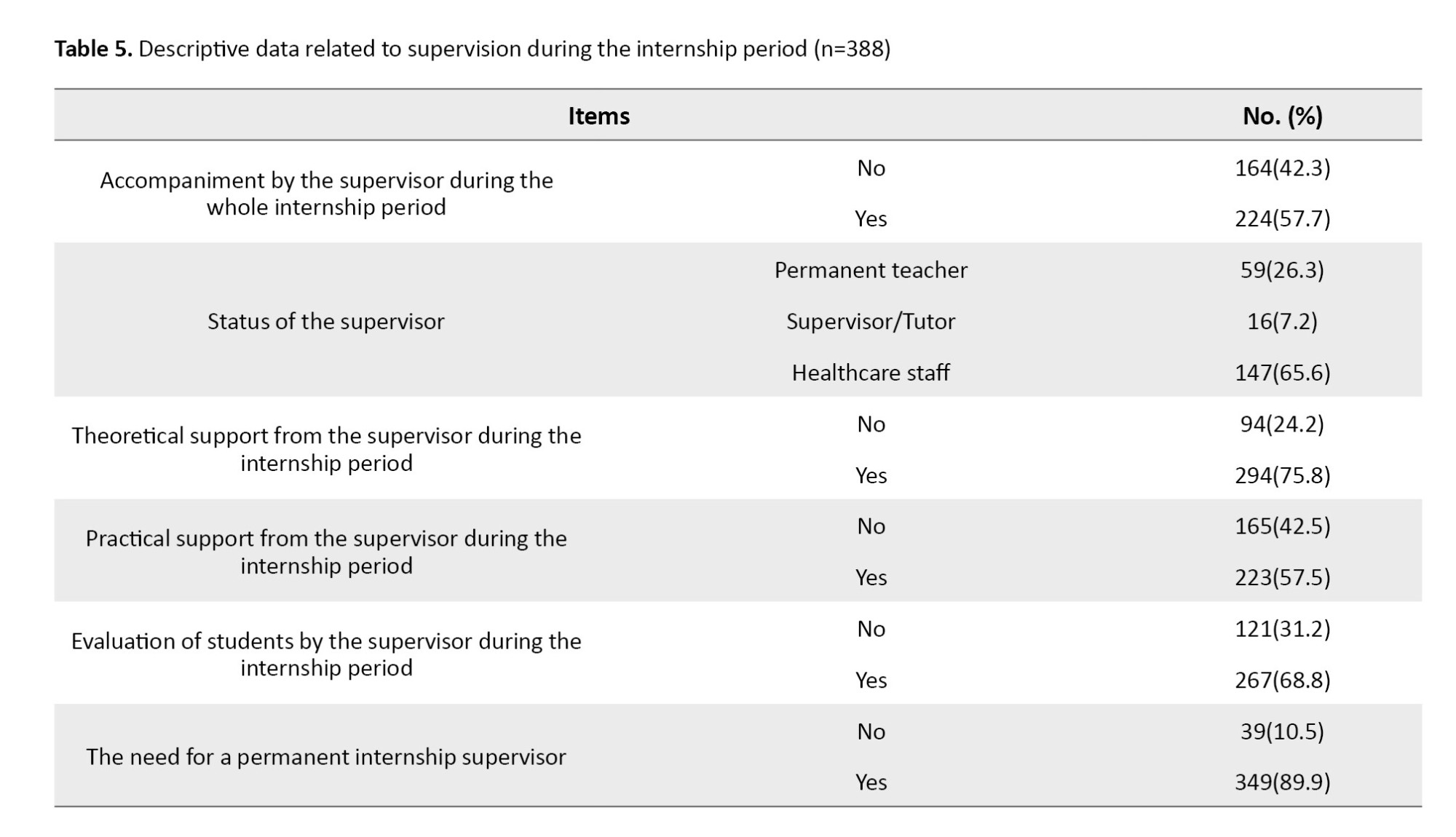

Regarding data related to supervision (Table 5), it was found that 57.7% received continuous supervision during the internship period. Most of the students had received theoretical (75.8%) and practical (57.5%) supports from their supervisors. Additionally, 68.8% had undergone the end-of-course assessments, and 89.9% expressed a need for a permanent internship supervisor.

Discussion

This study investigated the challenges faced by nursing students in Morocco during clinical education. The students reported positive perceptions of clinical placements as effective learning experiences. These findings align with research indicating the clinical setting is valuable for skill application [12, 13] and essential for developing cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills necessary for patient care [14]. Clinical placements also facilitate socialization and competency acquisition among students [15]. Most participants reported positive relationships with the healthcare team during clinical placements, indicating effective communication and collaboration, fostering a supportive learning environment. Also, learning primarily occurred through interaction with patients during the internship period.

Our study examined the concepts of “patient partner” and “care partnership” and revealed that most nursing students had genuine partnership experiences, where patients accepted them as learners. Patients frequently asked for information or explanations about their care from students, emphasizing the central role of patient care in student learning processes. This holistic approach fosters supportive relationships and prepares students for their future profession. Nearly all students reported a noticeable improvement in learning while participating in care activities, aligning with Phaneuf’s perspective on the importance of clinical practice in learners’ competency acquisition [16].

Regarding students’ perceptions of the internship setting, most students described that they were moderately welcomed on the first days of the internship period. This is consistent with the findings of a previous study [17]. It may be due to the negative or unwelcoming behavior of some staff members [18], due to the heavy clinical workload and the presence of students, which adds an extra layer of demand [19]. Most students indicated that the time allocated for the internship was insufficient. This is consistent with the findings of a study that indicated the short duration of internships, hindering students from engaging in meaningful learning experiences [17]. This time shortage deprives students of the opportunity to fully achieve the defined learning objectives, especially in clinical settings with rich learning opportunities, such as emergency, intensive care, and specialized units (oncology, neonatology, transplantation, etc.) [20]. Consequently, students may struggle to identify diverse clinical scenarios and may have limited exposure to appropriate patient management modalities, impeding the development of their nursing practice skills [4]. Regarding the internship goal achievement, more than half of the students believed that the goals were not achieved by them. This is consistent with the findings of Otti [17]. In Maamri et al.’s study [21], a significant number of students did not manage to achieve the assigned internship goals. Assessment in a clinical setting poses a significant challenge for nursing education [6]. It plays a crucial role in the teaching/learning process, affecting both student learning and teacher pedagogy [22-25]. However, our results revealed that almost one-third of students were not evaluated during their internships, despite the importance of assessment providing relevant information for their skill development [9].

The analysis of data related to supervision during the internship, revealed the dissatisfaction of students with their clinical supervisors. Clinical supervision can provide an opportunity for reflective practice and the development of clinical reasoning skills, benefiting both students and supervisors [26]. Regarding support from the healthcare team, the majority of students perceived the support. Support is vital for learning and stress reduction [6, 13, 27]. Support also promotes knowledge transfer, involving the application of different types of knowledge in various contexts [28]. This transfer process involves linking declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge in various situations [29, 30]. Nursing students’ stress varies from fear of patient harm to embarrassment from misunderstanding instructions [19]. In our study, 62.6% of students partially understood their tasks on the first day of the internship, and many of them were informed of learning activities in advance. Many students found that the activities offered in the clinical setting helped fill the gap between theoretical education and practical learning. This is consistent with the findings of a study conducted by Gallas in Tunisia [31], where 72.3% of participants managed to fill the gap between theory and practice. Close supervision is crucial for learning [32]. In our study, only about half of the students received close supervision. Low supervision may be due to the absence of formal regulations. The students expressed a need for the presence of a permanent supervisor for effective learning during the internship.

The findings of this study contribute to enhancing the quality of internship and the delivery of healthcare services in Morocco. We recommend the nursing curriculum reforms that consider the specificities of internship, including the sufficient time for clinical learning, more effective supervision strategies, and the creation of teaching/learning guidelines for clinical settings, and raising awareness among healthcare professionals to actively participate in the clinical supervision of interns. We also recommend further exploration of the internship settings and more related studies to improve nursing education and clinical supervision and educate competent professionals.

In conclusion, the results of our study highlight the existence of some challenges related to clinical education faced by nursing students in Morocco, which can have an impact on the quality of clinical education. Considering these constraints, it is necessary to implement a real strategy to improve the quality of internship in clinical settings. There is a need for supervisors in clinical settings, a sine qua non of effective internship.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research of the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Mohamed V University of Rabat, Morocco (Code: 09/21). All participants were informed that they are free to leave the study at any time. Their anonymity and confidentiality were also respected.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Fatima Zahra Laamiri and Amina Barakat; Data collection: Fatima Zahra Laamiri and Fatima Barich. Data analysis, writing, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their patience and cooperation.

References

In recent decades, nursing education has undergone reforms aligned with the Bologna principles, aimed at addressing issues such as mobility and employment of graduates by standardizing university qualifications [1]. The university curriculums allow students to learn the concepts essential for their professional practice, while facilitating adaptation to evolving contexts and potential transitions to other professional sectors. Morocco has adopted a training model for health education, which includes the reorganization of curriculums at institutions such as the Higher Institute of Health Sciences in Settat and Higher Institutes of Nursing Professions and Health Technique [2]. This paradigm shift was initiated by a decree in 1993 establishing educational institutes for health careers. Education in health sciences involves a combination of theoretical education and practical clinical learning, often referred to as internship or learning in a clinical setting. This hands-on experience exposes students to diverse situations and practices, challenging them to apply academic knowledge in real-world scenarios [3-5]. The primary goal of the internship is to enable learners to apply their acquired knowledge in practice, fostering authentic and complex learning experiences [6-8].

The internship program receives less time compared to academic education, and the reduction in clinical placement days limits learning opportunities for students. This reduction is attributed to guidelines mandating internship modules to span between 80 and 160 hours, which is a significant time gap in education at the national level, with African students in health science experiencing a 1.5-year lag compared to their European counterparts. Consequently, African students often serve as passive observers, lacking opportunities to apply defined learning objectives.

Critical care wards, such as emergency departments, intensive care units, and specialized units, offer rich learning environments [9]. However, the limited exposure may hinder students from identifying various clinical situations and developing essential skills in patient management and technical health practice. By investing in research and fostering collaboration between academic institutions, healthcare organizations, and frontline professionals, we can make strides towards higher-quality and more accessible healthcare for all citizens. This study aims to investigate the constraints that affect clinical learning in nursing students in Morocco.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive study was conducted between September and December 2021 at two academic institutions (the Higher Institute of Health Sciences in Settat and the Higher Institute of Nursing and Health Techniques in Rabat). These institutions were selected due to having a wide range of specialties in the field of nursing science.

For sampling, we employed a purposive sampling method, as a non-probabilistic approach. As a result, the sample size was not predetermined. A total of 400 questionnaires were distributed to nursing students from the two institutions who met the inclusion criteria and were studying at the level of interest. Out of 400, 388 students agreed to participate and returned completed questionnaires, representing a high response rate of 97%. The study included students currently enrolled in nursing programs who had completed one or more clinical internships. Students who did not declare informed consent were not included in the study.

A questionnaire was developed to explore the constraints and challenges encountered by students during their clinical education. The questionnaire had 37 multiple-choice, open-ended, and semi-open-ended questions to assess the following five domains: a) Sociodemographic information (such as age, gender, place of residence, institution name, year of education, field of study, option of training, as well as reasons for choosing the field of study), b) Factors related to students, focusing on their appreciation of the internship, the activities offered in the clinical setting, the transfer of theoretical and practical knowledge taught in the academic setting, satisfaction with clinical training, and reasons for their interest; c) Students’ relationship with the healthcare team and patients during their clinical education: This includes understanding how students interact with the healthcare team and patients, which is crucial for their professional development; d) Factors related to learning in the clinical setting, covering the planning of informational sessions before the internship, the quality of reception by healthcare team, the understanding of the student’s role from the first day, the learning situations proposed by supervisors, the availability and use of materials, the student’s appreciation of the time dedicated to the internship, site selection, and the achievement of objectives; e) The supervision, addressing the presence and guidance of a supervisor during learning activities in the clinical environment, as well as the ongoing assessment of students throughout their internship. The students were given a time of 30 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

To assess the ability of the instrument to represent the constraints of clinical education in nursing students, its content validity was determined. In this regard, the opinions of researchers and healthcare professionals with expertise in the related field were used. The reliability of the instrument was assessed based on internal consistency and reproducibility. The reproducibility was determined by test re-test method [10, 11]. In this regard, 15 participants completed the questionnaire at two different times with a three-week interval. The findings demonstrated an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.85, indicating the questionnaire’s strong test re-test reliability. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s α coefficient, which yielded a value of 0.80, reflecting substantial internal consistency across the items and confirming their relevance and alignment with the measured constructs.

The collected data were analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software, version 20. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the normality of data distribution for the quantitative variables. This test revealed a normal distribution for the variable “student age” and was expressed in Mean±SD. Qualitative variables were expressed in frequency and percentage.

Results

Analysis of the sociodemographic data (Table 1) revealed that most of the students were female (84.5%). The mean age of the students was 20.42±1.37 years, ranging from 19 to 26 years. In terms of specialty, there were four types of participants: General nurses (70.9%), emergency and intensive care nurses (12.9%), anesthesia and resuscitation nurses (9.2%), and pediatrics and neonatal nurses (7%). The majority of the students (69.3%) reported that they chose their field of study based on a personal decision, while for 17.8% it was for the interesting prospects of the nursing profession, and for 12.98% it was because of the human quality of their future profession.

Regarding the data related to students’ involvement in clinical education (Table 2), it was found that more than half of the participants perceived that the clinical setting was effective for clinical learning (67%) and the training activities helped transfer theoretical knowledge (62.1%). Many appreciated the training for its authentic learning context (53.27%), professional team integration (31.37%), or other reasons (15.36%). However, 68.3% were dissatisfied with their clinical supervision, while 15.2% were satisfied or indifferent.

Regarding the data related to students’ relationship with the healthcare team (Table 3), it was found that most of the students had a positive relationship with healthcare team members (90%), received clear instructions (80%), were involved in care activities (76.5%), and perceived the support from the nursing staff (65.7%). Students were generally accepted by patients (72.9%), although some faced difficulties such as language barriers and patient distrust (79.4%). Almost all students (96.4%) reported that participating in care activities was crucial for skill development, and 88.9% felt capable of transferring theoretical knowledge to clinical settings.

Regarding the data related to learning in clinical settings (Table 4), it was found that 82.7% of students had received a pre-service briefing from different channels, specifically from the program coordinator (48.8%), during a session organized by the educational staff (24.7%), or from the internship guide (15.7%). According to 64.7% of students, the quality of internship welcome was moderate, and 62.6% had a partial understanding of their role during the first days of the internship. Also, 68% stated that the nursing leaders had provided them with the necessary equipment for patient care, and 58.2% mentioned that they occasionally used the provided equipment for their internship activities. Additionally, 71.6% believed that the time dedicated to the internship was insufficient, and almost 60% reported that the internship sites selected for their practical learning were at a moderate level. More than half of the students (57%) reported unmet internship goals. Almost all students (92%) reported a progression in learning when participating in care activities during semesters or the academic year. However, nearly one-third of the students reported not being evaluated during their internship, and the majority (82.2%) encountered constraints in the clinical setting.

Regarding data related to supervision (Table 5), it was found that 57.7% received continuous supervision during the internship period. Most of the students had received theoretical (75.8%) and practical (57.5%) supports from their supervisors. Additionally, 68.8% had undergone the end-of-course assessments, and 89.9% expressed a need for a permanent internship supervisor.

Discussion

This study investigated the challenges faced by nursing students in Morocco during clinical education. The students reported positive perceptions of clinical placements as effective learning experiences. These findings align with research indicating the clinical setting is valuable for skill application [12, 13] and essential for developing cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills necessary for patient care [14]. Clinical placements also facilitate socialization and competency acquisition among students [15]. Most participants reported positive relationships with the healthcare team during clinical placements, indicating effective communication and collaboration, fostering a supportive learning environment. Also, learning primarily occurred through interaction with patients during the internship period.

Our study examined the concepts of “patient partner” and “care partnership” and revealed that most nursing students had genuine partnership experiences, where patients accepted them as learners. Patients frequently asked for information or explanations about their care from students, emphasizing the central role of patient care in student learning processes. This holistic approach fosters supportive relationships and prepares students for their future profession. Nearly all students reported a noticeable improvement in learning while participating in care activities, aligning with Phaneuf’s perspective on the importance of clinical practice in learners’ competency acquisition [16].

Regarding students’ perceptions of the internship setting, most students described that they were moderately welcomed on the first days of the internship period. This is consistent with the findings of a previous study [17]. It may be due to the negative or unwelcoming behavior of some staff members [18], due to the heavy clinical workload and the presence of students, which adds an extra layer of demand [19]. Most students indicated that the time allocated for the internship was insufficient. This is consistent with the findings of a study that indicated the short duration of internships, hindering students from engaging in meaningful learning experiences [17]. This time shortage deprives students of the opportunity to fully achieve the defined learning objectives, especially in clinical settings with rich learning opportunities, such as emergency, intensive care, and specialized units (oncology, neonatology, transplantation, etc.) [20]. Consequently, students may struggle to identify diverse clinical scenarios and may have limited exposure to appropriate patient management modalities, impeding the development of their nursing practice skills [4]. Regarding the internship goal achievement, more than half of the students believed that the goals were not achieved by them. This is consistent with the findings of Otti [17]. In Maamri et al.’s study [21], a significant number of students did not manage to achieve the assigned internship goals. Assessment in a clinical setting poses a significant challenge for nursing education [6]. It plays a crucial role in the teaching/learning process, affecting both student learning and teacher pedagogy [22-25]. However, our results revealed that almost one-third of students were not evaluated during their internships, despite the importance of assessment providing relevant information for their skill development [9].

The analysis of data related to supervision during the internship, revealed the dissatisfaction of students with their clinical supervisors. Clinical supervision can provide an opportunity for reflective practice and the development of clinical reasoning skills, benefiting both students and supervisors [26]. Regarding support from the healthcare team, the majority of students perceived the support. Support is vital for learning and stress reduction [6, 13, 27]. Support also promotes knowledge transfer, involving the application of different types of knowledge in various contexts [28]. This transfer process involves linking declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge in various situations [29, 30]. Nursing students’ stress varies from fear of patient harm to embarrassment from misunderstanding instructions [19]. In our study, 62.6% of students partially understood their tasks on the first day of the internship, and many of them were informed of learning activities in advance. Many students found that the activities offered in the clinical setting helped fill the gap between theoretical education and practical learning. This is consistent with the findings of a study conducted by Gallas in Tunisia [31], where 72.3% of participants managed to fill the gap between theory and practice. Close supervision is crucial for learning [32]. In our study, only about half of the students received close supervision. Low supervision may be due to the absence of formal regulations. The students expressed a need for the presence of a permanent supervisor for effective learning during the internship.

The findings of this study contribute to enhancing the quality of internship and the delivery of healthcare services in Morocco. We recommend the nursing curriculum reforms that consider the specificities of internship, including the sufficient time for clinical learning, more effective supervision strategies, and the creation of teaching/learning guidelines for clinical settings, and raising awareness among healthcare professionals to actively participate in the clinical supervision of interns. We also recommend further exploration of the internship settings and more related studies to improve nursing education and clinical supervision and educate competent professionals.

In conclusion, the results of our study highlight the existence of some challenges related to clinical education faced by nursing students in Morocco, which can have an impact on the quality of clinical education. Considering these constraints, it is necessary to implement a real strategy to improve the quality of internship in clinical settings. There is a need for supervisors in clinical settings, a sine qua non of effective internship.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research of the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Mohamed V University of Rabat, Morocco (Code: 09/21). All participants were informed that they are free to leave the study at any time. Their anonymity and confidentiality were also respected.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Fatima Zahra Laamiri and Amina Barakat; Data collection: Fatima Zahra Laamiri and Fatima Barich. Data analysis, writing, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their patience and cooperation.

References

- Hajayandi N. [The reform of the “License Master Doctorate” system of higher education in Burundi: issues and new requirements (French)]. Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review. 2020;23 (54): 1-14. [DOI:10.4000/eastafrica.1186]

- Barich F, Chamkal N, Rezzouk B. [Training in nursing and technical health in the bachelor’s master’s doctorate system in Morocco: Analysis of training descriptions (descriptive analytical study) (French)]. Revue Francophone Internationale de Recherche Infirmière. 2019; 5(4):100183. [DOI:10.1016/j.refiri.2019.100183]

- Zhang J, Shields L, Ma B, Yin Y, Wang J, Zhang R, Hui X. The clinical learning environment, supervision and future intention to work as a nurse in nursing students: A cross-sectional and descriptive study. BMC Medical Education. 2022; 22(1):548. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-022-03609-y] [PMID]

- Sahadevan S, Kurian N, Mani AM, Kishor MR, Menon V. Implementing competency-based medical education curriculum in undergraduate psychiatric training in India: Opportunities and challenges. Asia-Pacific psychiatry: Official Journal of the Pacific Rim College of Psychiatrists. 2021; 13(4):e12491. [PMID]

- Jouquan J. [Comment (mieux) superviser les étudiants en sciences de la santé dans leurs stages et dans leurs activités de recherche ? (French)]. Pédagogie Médicale. 2018; 19:51-2. [Link]

- Saarikoski M. The main elements of clinical learning in healthcare education. The CLES-scale: An evaluation tool for healthcare education. In: Saarikoski M, Strandell-Laine C, editors. The CLES-Scale: An evaluation tool for healthcare education. Cham: Springer; 2018. [Link]

- Rahimi M, Haghani F, Kohan S, Shirani M. The clinical learning environment of a maternity ward: A qualitative study. Women and Birth. 2019; 32(6):e523-9. [PMID]

- Binder JF, Baguley T, Crook C, Miler F. The academic value of internships: Benefits across disciplines and student backgrounds. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2015; 41: 73–82. [DOI: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.12.00]

- Inayat S, Younas A, Sundus A, Khan FH. Nursing students’ preparedness and practice in critical care settings: A scoping review. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2021; 37(1):122-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.06.007] [PMID]

- Fortin MF, Gagnon J. [Foundations and Steps of the Research Process, 4th Edition: Quantitative and qualitative methods (French)]. Montréal: Cheneliere Education; 2016. [Link]

- Hobart JC, Riazi A, Lamping DL, Fitzpatrick R, Thompson AJ. Improving the evaluation of therapeutic interventions in multiple sclerosis: Development of a patient-based measure of outcome. Health Technology Assessment. 2004; 8(9):iii, 1-48. [PMID]

- May Bella J. Teaching: A skill in clinical practice. Physical Therapy. 1983; 63(10):1627–33. [DOI:10.1093/ptj/63.10.1627]

- Houghton CE, Casey D, Shaw D, Murphy K. Students’ experiences of implementing clinical skills in the real world of practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2013; 22(13-14):1961-9. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.12014]

- Birks M, Bagley T, Park T, Burkot C, Mills J. The impact of clinical placement model on learning in nursing: A descriptive exploratory study. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2017; 34(3):16‑23. [Link]

- Lee JJ, Yang SC. Professional socialisation of nursing students in a collectivist culture: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education. 2019; 19(254):1-8. [Link]

- Phaneuf M. [The caregiver-patient relationship, 2nd edition - Therapeutic support (French)]. Montréal : Chenelière Education; 2016. [Link]

- Otti A, Pirson M, et Piette D. Perception of the management and the quality of the clinical pedagogical supervision in nursing and obstetric sciences by INMeS students in Benin, a quantitative and qualitative transversal descriptivestudy. International Francophone Journal of Nursing Research. 2015; 1(3):169-78. [DOI:10.1016/j.refiri.2015.06.001]

- Froneman K, Du Plessis E, Koen MP. Effective educator-student relationships in nursing education to strengthen nursing students’ resilience. Curationis. 2016; 39(1):1595. [PMID]

- Bazrafkan L, Najafi Kalyani M. Nursing students experiences of clinical education: A qualitative study. Investigacion y Educacion en Enfermeria. 2018; 36(3):10.17533/udea.iee.v36n3e04. [DOI:10.17533/udea.iee.v36n3e04] [PMID]

- Lasnier F. [An integrated model for learning a skill (French)]. Proceedings of the 21st AQPC Colloquium. Quebec Association of College Pedagogy. 2001. [Link]

- Maamri A. [Qualité de l'enseignement pratique et théorique des lauréats de l'IFCS d'Oujda, MAROC (French)] [MA thesis]. Normandy: Université de Rouen; 2007. [Link]

- Harsi EL Mahjoub EL, Mouad Aouzal. [Factors influencing the evaluation of learning in a clinical setting of students in a higher institute of nursing and health techniques in Morocco: An exploratory descriptive study (French)]. Revue Francophone Internationale de Recherche Infirmière. 2021; 7(4):100248. [DOI:10.1016/j.refiri.2021.100248]

- Tomas N, Aukelo M, Tomas TN. Factors influencing undergraduate nursing students’ evaluation of teaching effectiveness in a nursing program at a higher education institution in Namibia. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2022; 17:100494. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijans.2022.100494]

- Amoo SA, Aderoju YBG, Sarfo-Walters R, Doe PF, Okantey C, Boso CM, et al. Nursing students’ perception of clinical teaching and learning in Ghana: A descriptive qualitative study. Nursing Research and Practice. 2022; ;2022:7222196. [PMID]

- Oermann MH, Gaberson KB, De Gagne JC. Evaluation and testing in nursing education. Springer Publishing Company; 2025. [Link]

- Otti A, Piette D, Goudreau J, Piette D, Coppieters Y. [Un outil d’analyse de la qualité de la supervision clinique en sciences infirmières (French)]. L’infirmière clinicienne. 2017; 14(1) :30-44. [Link]

- Zheng YX, Jiao JR, Hao WN. Stress levels of nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2022 ; 101(36):e30547. [PMID]

- Lauzier M, Denis D. [Increasing the transfer of learning: Towards new knowledge (French)]. Quebec: Practices and Experiences. 2020. [Link]

- Barbeau D, Montini A, Roy C. [Tracing the Paths of Knowledge (French)]." Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference of the Quebec Association of College Pedagogy. Quebec Association of College Pedagogy. 1997. [Link]

- Yun J, Kim DH, Park Y. The influence of informal learning and learning transfer on nurses’ clinical performance: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Nurse Education Today. 2019; 80:85‑90. [PMID]

- Gallas S. [Perception of nursing students on their training in the field of interpersonal skills (French)]. Revue francophone Internationale de Recherche Infirmière. 2018; 4(1):56-63. [Link]

- Ismail LMN, Aboushady RMN, Eswi A. Clinical instructor’s behavior: Nursing student’s perception toward effective clinical instructor’s characteristics. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice. 2016; 6(2):96. [DOI:10.5430/jnep.v6n2p96]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2023/01/18 | Accepted: 2024/04/30 | Published: 2025/01/7

Received: 2023/01/18 | Accepted: 2024/04/30 | Published: 2025/01/7

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |