Fri, Apr 26, 2024

Volume 29, Issue 4 (9-2019)

JHNM 2019, 29(4): 243-251 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shaali M, Farajzadegan Z, Turk Nezhad Azerbaijani A, Boroumandfar Z. Self-efficacy and Self-esteem in Wives With Addicted Husbands. JHNM 2019; 29 (4) :243-251

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-994-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-994-en.html

1- Midwifery(MSc), Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

2- Associate Professor, Department of Community Medicine, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Psychiatrist, Imperial College London, England.

4- Assistant Professor, Department of Reproductive Health and Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. , boroumandfar@nm.mui.ac.ir

2- Associate Professor, Department of Community Medicine, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Psychiatrist, Imperial College London, England.

4- Assistant Professor, Department of Reproductive Health and Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. , boroumandfar@nm.mui.ac.ir

Full-Text [PDF 497 kb]

(679 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2587 Views)

Full-Text: (1206 Views)

Introduction

ddiction and substance use disorder is a widespread bio-psychosocial phenomenon that causes many social disorders and abnormalities [1]. Addiction is one of the most significant psychosocial disorders that can easily disrupt the foundation of individual, family, social, and cultural life of a society [2]. Nowadays, addictive disorders are considered as one of the most serious problems for health managers and planners in many parts of the world [3]. It is estimated that one billion people, or about (5%) of the world’s adult population, have used drugs at least once in 2015 [4]. Iran Drug Control Headquarters stated that there are 2.800.000 drug users in Iran and the adverse effects of drug abuse are mainly targeted the husband, parents, and children of the addicted person [5, 6]. Thus, conflict, stress, and disturbing relationships in a family may lead to low self-esteem, lack of independence, and impaired socialization [7]. The father’s addiction to a drug is social harm in these families. The father of the family affects the social relations of the family members, and his addiction leads to the disruption of the family and the deterioration of the relationships among the family members [8].

Since the family is the most vulnerable social institution concerning the adverse effects of drug addiction, and the addicted householder is unable to fulfill his role as the husband and father, the importance of the wife’s role doubles in families with an addicted householder [9]. The presence of such a person who has a substance abuse problem is stressful and can have a damaging effect on the life of family members, especially the husband [10]. The results of some studies confirm a relationship between substance abuse and psychiatric disorders [11, 12]. On the other hand, these damaging behaviors have a significant effect on psychological indices, such as self-efficacy and self-esteem of other family members [9].

Wives of addicted husbands experience some psychological and physical symptoms, such as anxiety about the burden of addiction, concerns about the drug user’s behavior and his condition of physical and mental health, decline in family social communication, adverse effects on the interaction among the family members (importance of family interpersonal relationships), and attitude or mood symptoms. Because addicted people are also more likely to develop personality disorders, anger, and aggression than ordinary people, their wives have lower social support [13-16].

Research also shows that women living with an addicted husband compared to normal women have more behavioral problems such as substance abuse, sexual relations outside of marriage, as well as physical symptoms, including anxiety, insomnia, and ultimately poor quality of life [17]. Another study also confirms that drug abuse in addicted people results in lack of self-esteem, social and behavioral isolation, social problems, financial pressures, feelings of fear and anxiety among other members of the family [18]. In addition, the results of a study also show significant stress, psychological distress, and lower self-esteem in the family members of addicted people compared to the control group [19].

It seems that these women are experiencing challenging lives; thus the present study, with a qualitative approach tries to identify the nature of the problem, presents a profound definition and explanation of the phenomenon and the women’s description of self-efficacy and self-esteem with addicted husbands.

Materials and Methods

The present study is qualitative research using conventional content analysis. The participants consisted of 20 women referring to Social Welfare Center in Isfahan City, Iran, from September to November 2016. The inclusion criteria included being 18-50 years old, providing informed consent to participate in the study, and lacking any physical and mental illness based on their report. The samples were chosen by purposive sampling method until data saturation, which was attained after performing 17 interviews. Three more interviews were also conducted to ensure the accuracy of the data. The sampling was done considering the highest variation in the duration of drug use, type of drugs used, differences in age, education, marital, economic, and social status of the participants.

In-depth, face-to-face, and semi-structured interviews started with some leading vital questions such as: “Did you know about your husband’s addiction when you got married?” “Explain the condition of life while your husband was consuming drugs?” “What effect did these conditions have on your husband?” “What was the effect on you?” “How do you feel about yourself?” “How do others feel about you?” “What conditions do you need to change all these things?” and “What do you need to do to regain self-esteem and manage your work properly?” The next questions were based on the issues recalled and expressed by the participants. In addition, some clarifying questions like “What do you mean?” “Please explain more about this?” or “It is my understanding of your words, am I right?” were asked to go deeper into the interview.

The interviews lasted 30-60 minutes. They were transcribed verbatim 48 hours later and then data were prepared. To analyze the obtained data, the qualitative content analysis of Graneheim and Lundman approach was used in this study [20]. According to this approach, data analysis started from the first interview and continued with other interviews (simultaneous analysis). In this analysis, the texts were read several times to gain an overall understanding of it and then line by line to give a theme to the main concepts of these sentences. By comparing the categories with each other, a list of main categories and subcategories was obtained. The researchers classified and encoded these categories, and then compared them with each other.

Common criteria for acceptance in qualitative research such as verification, reliability, and transferability were considered through techniques such as participants revisions, systematic data collection, early copying, peer reviews, total re-reading, as well as transferability through an interview with different contributors, and providing direct quotes and examples and rich explanations of the data [21].

Results

There were 20 participants in this study. Their Mean±SD age was 33.5±7.6 years. Of them, 65.6% passed elementary school, 96.6% had children, and 87.7% were housewives. The Mean±SD years of drug use of their husbands were 15.5±7 years.

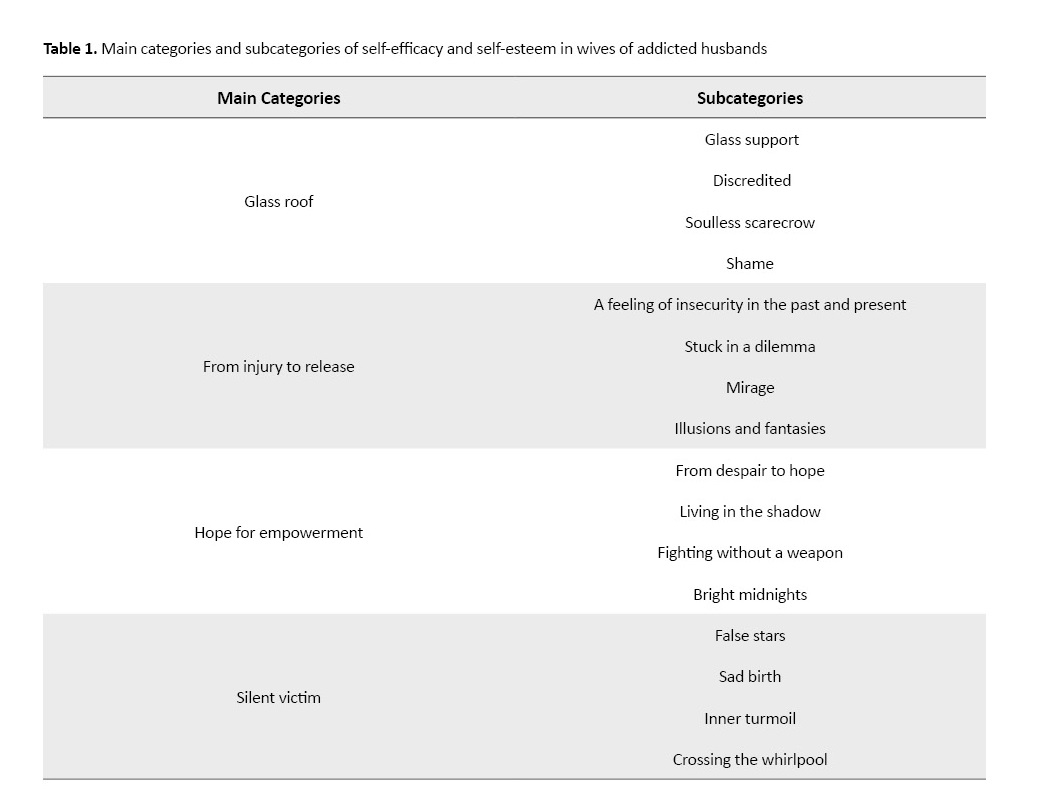

Based on the results of the data analysis on self-efficacy and self-esteem in women with drug-use husbands, there are four main categories of “glass roof”, “from injury to relief”, “hope for empowerment”, and “silent victim”, and 16 subcategories (Table 1).

The first category (Glass roof)

The study women’s thought of their husbands’ support in the family and society burdened with the word “addiction”. The participants described this “glass roof” as a “glass support”, “discredited”, “soulless scarecrow”, and “shame”.

Glass support

The participants mentioned living with an addicted husband as a glass stand whose existence does not feel in facing everyday life problems. They believed that it was not a shelter but a glass roof that may break and fall on the family at any moment.

“... My husband’s conditions affected me, fallen apart, disappointed with my husband, and exhausted. Life seems terrible. I can only rely on myself, so I lost my tranquility because of such a heavy burden (She repeatedly said alas, alas) and I don’t have anyone” (Participant No. 3).

Discredited

It was one of the subcategories that participants felt living under the glass roof. They declared that such feeling of discredit burned the root of beliefs and behaviors of self-efficacy and self-esteem in them.

“... I cannot afford the expense and cost of children’s education. I refused to tell their school authorities that their father is addicted to drugs because they would say how he could afford the drugs but not school fee. So I told their school that their father was sick. In school, all students have books, but my daughter doesn’t. Also, my son has no clothes and goes to school with home clothes” (Participant No. 6).

Soulless scarecrow

Almost all participants acknowledged that their husbands’ addiction was like a soulless scarecrow that drove him out of the position of responsible father and husband. The world means nothing for him but taking the drug. The drug is all his life. He has no feelings for himself and others. Like a scarecrow who steals its eyes from the facts of life.

“... addiction made him beat me. As if he is a body without a soul. As if nothing is going on in this world. Wife and children are not important for him just drug and drowning in his thoughts” (Participant No. 5).

Shame

A great deal of inner shame was felt in the participants. According to them, the shame of not telling the truth, and the shame of having an addicted husband all her life.

“... I feel ashamed and embarrassed wherever I go, and I’m ashamed to say that I have a husband, but he is a drug addict” (Participant No. 10).

The second category (From injury to relief)

The participants suffered from living in the past. They attributed most of the events of today and tomorrow to their past and hurtful experiences. They sometimes preferred another life to escape from that situation and realities. So, it is possible to understand their “feeling of insecurity in the past and present”, “stuck in a dilemma”, “mirages” and “illusions and fantasies”.

Feeling insecure in the past and present

Most participants reported a feeling of insecurity in their childhood. According to them, this feeling did not resolve by escaping from it but worsened by living with an addicted husband.

“... to escape living with my father and brothers and their harassment, I married a man who was beating me from the beginning so that I got injured to the death and fainted. He did not understand that I am a human and not supposed to pay for his sins. If I died under his kicks, no one would give me a hand. I was afraid of him. I always thought death was near me, and when I got pregnant, he was always out with his friends until night. He was not even home for some nights. He did not know himself responsible for anything in life. Sometimes he came home being kicked out and in blood. Every day I blamed myself for being pregnant endangering myself as well as my baby” (Participant No. 13).

Stuck in a dilemma

Most participants said that they were wandering between belief in failure/disability and hoping at success/ability. They thought that having an addicted husband would transfer them the feeling of failure and disability, and they were looking for a way to regain hope:

“... my life is an absolute mess. I can’t go on. I’m lost. I don’t like working. I have a carpet at home to weave, but I can’t work anymore. I’ve no motivation to work. Feel fatigued and heartbroken. But if a way appears or a class to start again and somebody takes my hand. No one listens to me, as if I do not exist” (Participant No. 1).

Mirage

Most of the participants lived in broken families and now believed that because of their adverse life events, including their husbands’ addiction, they received pessimistic views from others and themselves.

“... others have a terrible notion about me. They are cynical. When I walk out, my neighbors and family ask where you were and where you went. I don’t like to go out anymore. I used to be in meetings and among other people a lot, but now I don’t want to. Everyone wants to know about my life” (Participant No. 14).

Illusion and fantasy

The illusion of loving and being loved by the husbands suffered these women. All of them believed that they were being loved.

“... my husband loved me. Maybe he loved me. Perhaps I was dreaming. Always an absurd thought is choking me; a lump in the throat, which I could never believe. Because he betrayed me, he said you are not like others. He humiliated me. That made me lose my life, and I lost” (Participant No. 9).

The third category (Hope for empowerment)

Believing in and ultimately doing some behaviors representing such expressions as “I can’t do”, “I don’t know”, and “I’m tired” are phrases mostly heard from the participants. They described their experiences of self-efficacy and self-esteem in the course of living with an addicted person as “from despair to hope”, “living in the shadow”, “fighting without a weapon”, and “bright midnights”.

From despair to hope

The vast majority of participants believed that hope and children were the only reasons they continue to live:

“... all my life are my kids. There is nothing left for me to think about myself. Things are messed up. I’m just delighted with my kids, hoping they won’t become like their father” (Participant No. 17).

Living in the shadow

In the words of the participants, the days passing by women were foggy and misty because their living environment was on the outskirts of the city, and there were no suitable facilities for them.

“... my brothers were addicted there. People were consuming drugs together. Perhaps a normal action! I accepted that I had to give up in this situation” (Participant No. 10).

Fighting without a weapon

The participants rarely believed that because of having an addicted husband, they are fighting against the challenges of life with no confidence and sense of worthiness.

“... after I worked hard from morning till night to provide a home for the family, my husband and his family tried to take home from me. However, I built it with my life. Now I destroy it myself again, even though the pressures on me are too much, and there are lots of ‘I can’ts’ in my head” (Participant No. 11).

Bright midnights

Most of the participants believed that their good days are gone and whenever they remember them, they feel happy. They thought that despite all fears and troubles of life, a star is shining in the dark.

“... my good days were when my kids were born. We had no fun and still don’t. But when I remember my mom, good childhood days that passed by without difficulties, those days were the best days of my life [crying], I wish those days would come back” (Participant No. 2).

The fourth category (Silent victim)

There was a fire in the eyes and hearts of the wives of addicted men, which suppressed because of severe personal, family, and social vulnerabilities. In the meantime, the participants used “false stars”, “sad birth”, “inner turmoil”, and “crossing the whirlpool” to acknowledge their inefficiency, inadequacy, and low self-esteem in the process of their husband’s addiction.

False stars

The participants analogized their early life with their husbands, a dream man, to a false, dark star like a prince riding a horse.

“... When I saw him, I felt like he was the man for whom I was always waiting. He was the only person who could make me happy, and I felt I was the most beautiful woman on earth. But as the days passed by, I could see the warm days substituting by the cold smoke that darkened my whole life” (Participant No. 16).

Sad birth

Every day, the participants were thinking about the cause of their birth. They often complained about coming into a world that had nothing but constant cries of pain and agony. They consider their inefficiency in their very existence, that means their being born to this world and that feeling made the conditions worse for them every day.

“… I’m always crying. I’m depressed. I don’t want to talk to anyone. It hurts to see people. I wish I hadn’t been born. My mom gave birth to my misery. I hate life. I hate working. I can’t do anything” (Participant No. 12).

Inner turmoil

The participants expressed their indescribable aches and pains in the chaos of their lives and talked about their wishes and longing for prosperity in their lives.

“… my husband’s addiction and his behavior made me mentally ill. I feel jealous of people’s lives. Even my family doesn’t care about me. Because I’m so weak. Beside anyone I sit, he will go and leave away. To everyone, I say hello, he thinks it’s for money. I hate this world and the constantly saying of “why me” bothers me from inside” (Participant No. 7).

Crossing the whirlpool

The participants believed that inaccurate information about life issues, along with an addicted husband, swallowed them like a whirlpool.

“... I did not want to get married. But I got married at my father’s insistence that first the elder sis and then the younger one. I became a miserable person because of my sister. Because he was an addict. But I didn’t know what addiction was. Later, I gave birth to a baby. Because I didn’t know how to prevent it and they told me a child might make your husband act wisely. But it didn’t. Things got worse” (Participant No. 20).

ddiction and substance use disorder is a widespread bio-psychosocial phenomenon that causes many social disorders and abnormalities [1]. Addiction is one of the most significant psychosocial disorders that can easily disrupt the foundation of individual, family, social, and cultural life of a society [2]. Nowadays, addictive disorders are considered as one of the most serious problems for health managers and planners in many parts of the world [3]. It is estimated that one billion people, or about (5%) of the world’s adult population, have used drugs at least once in 2015 [4]. Iran Drug Control Headquarters stated that there are 2.800.000 drug users in Iran and the adverse effects of drug abuse are mainly targeted the husband, parents, and children of the addicted person [5, 6]. Thus, conflict, stress, and disturbing relationships in a family may lead to low self-esteem, lack of independence, and impaired socialization [7]. The father’s addiction to a drug is social harm in these families. The father of the family affects the social relations of the family members, and his addiction leads to the disruption of the family and the deterioration of the relationships among the family members [8].

Since the family is the most vulnerable social institution concerning the adverse effects of drug addiction, and the addicted householder is unable to fulfill his role as the husband and father, the importance of the wife’s role doubles in families with an addicted householder [9]. The presence of such a person who has a substance abuse problem is stressful and can have a damaging effect on the life of family members, especially the husband [10]. The results of some studies confirm a relationship between substance abuse and psychiatric disorders [11, 12]. On the other hand, these damaging behaviors have a significant effect on psychological indices, such as self-efficacy and self-esteem of other family members [9].

Wives of addicted husbands experience some psychological and physical symptoms, such as anxiety about the burden of addiction, concerns about the drug user’s behavior and his condition of physical and mental health, decline in family social communication, adverse effects on the interaction among the family members (importance of family interpersonal relationships), and attitude or mood symptoms. Because addicted people are also more likely to develop personality disorders, anger, and aggression than ordinary people, their wives have lower social support [13-16].

Research also shows that women living with an addicted husband compared to normal women have more behavioral problems such as substance abuse, sexual relations outside of marriage, as well as physical symptoms, including anxiety, insomnia, and ultimately poor quality of life [17]. Another study also confirms that drug abuse in addicted people results in lack of self-esteem, social and behavioral isolation, social problems, financial pressures, feelings of fear and anxiety among other members of the family [18]. In addition, the results of a study also show significant stress, psychological distress, and lower self-esteem in the family members of addicted people compared to the control group [19].

It seems that these women are experiencing challenging lives; thus the present study, with a qualitative approach tries to identify the nature of the problem, presents a profound definition and explanation of the phenomenon and the women’s description of self-efficacy and self-esteem with addicted husbands.

Materials and Methods

The present study is qualitative research using conventional content analysis. The participants consisted of 20 women referring to Social Welfare Center in Isfahan City, Iran, from September to November 2016. The inclusion criteria included being 18-50 years old, providing informed consent to participate in the study, and lacking any physical and mental illness based on their report. The samples were chosen by purposive sampling method until data saturation, which was attained after performing 17 interviews. Three more interviews were also conducted to ensure the accuracy of the data. The sampling was done considering the highest variation in the duration of drug use, type of drugs used, differences in age, education, marital, economic, and social status of the participants.

In-depth, face-to-face, and semi-structured interviews started with some leading vital questions such as: “Did you know about your husband’s addiction when you got married?” “Explain the condition of life while your husband was consuming drugs?” “What effect did these conditions have on your husband?” “What was the effect on you?” “How do you feel about yourself?” “How do others feel about you?” “What conditions do you need to change all these things?” and “What do you need to do to regain self-esteem and manage your work properly?” The next questions were based on the issues recalled and expressed by the participants. In addition, some clarifying questions like “What do you mean?” “Please explain more about this?” or “It is my understanding of your words, am I right?” were asked to go deeper into the interview.

The interviews lasted 30-60 minutes. They were transcribed verbatim 48 hours later and then data were prepared. To analyze the obtained data, the qualitative content analysis of Graneheim and Lundman approach was used in this study [20]. According to this approach, data analysis started from the first interview and continued with other interviews (simultaneous analysis). In this analysis, the texts were read several times to gain an overall understanding of it and then line by line to give a theme to the main concepts of these sentences. By comparing the categories with each other, a list of main categories and subcategories was obtained. The researchers classified and encoded these categories, and then compared them with each other.

Common criteria for acceptance in qualitative research such as verification, reliability, and transferability were considered through techniques such as participants revisions, systematic data collection, early copying, peer reviews, total re-reading, as well as transferability through an interview with different contributors, and providing direct quotes and examples and rich explanations of the data [21].

Results

There were 20 participants in this study. Their Mean±SD age was 33.5±7.6 years. Of them, 65.6% passed elementary school, 96.6% had children, and 87.7% were housewives. The Mean±SD years of drug use of their husbands were 15.5±7 years.

Based on the results of the data analysis on self-efficacy and self-esteem in women with drug-use husbands, there are four main categories of “glass roof”, “from injury to relief”, “hope for empowerment”, and “silent victim”, and 16 subcategories (Table 1).

The first category (Glass roof)

The study women’s thought of their husbands’ support in the family and society burdened with the word “addiction”. The participants described this “glass roof” as a “glass support”, “discredited”, “soulless scarecrow”, and “shame”.

Glass support

The participants mentioned living with an addicted husband as a glass stand whose existence does not feel in facing everyday life problems. They believed that it was not a shelter but a glass roof that may break and fall on the family at any moment.

“... My husband’s conditions affected me, fallen apart, disappointed with my husband, and exhausted. Life seems terrible. I can only rely on myself, so I lost my tranquility because of such a heavy burden (She repeatedly said alas, alas) and I don’t have anyone” (Participant No. 3).

Discredited

It was one of the subcategories that participants felt living under the glass roof. They declared that such feeling of discredit burned the root of beliefs and behaviors of self-efficacy and self-esteem in them.

“... I cannot afford the expense and cost of children’s education. I refused to tell their school authorities that their father is addicted to drugs because they would say how he could afford the drugs but not school fee. So I told their school that their father was sick. In school, all students have books, but my daughter doesn’t. Also, my son has no clothes and goes to school with home clothes” (Participant No. 6).

Soulless scarecrow

Almost all participants acknowledged that their husbands’ addiction was like a soulless scarecrow that drove him out of the position of responsible father and husband. The world means nothing for him but taking the drug. The drug is all his life. He has no feelings for himself and others. Like a scarecrow who steals its eyes from the facts of life.

“... addiction made him beat me. As if he is a body without a soul. As if nothing is going on in this world. Wife and children are not important for him just drug and drowning in his thoughts” (Participant No. 5).

Shame

A great deal of inner shame was felt in the participants. According to them, the shame of not telling the truth, and the shame of having an addicted husband all her life.

“... I feel ashamed and embarrassed wherever I go, and I’m ashamed to say that I have a husband, but he is a drug addict” (Participant No. 10).

The second category (From injury to relief)

The participants suffered from living in the past. They attributed most of the events of today and tomorrow to their past and hurtful experiences. They sometimes preferred another life to escape from that situation and realities. So, it is possible to understand their “feeling of insecurity in the past and present”, “stuck in a dilemma”, “mirages” and “illusions and fantasies”.

Feeling insecure in the past and present

Most participants reported a feeling of insecurity in their childhood. According to them, this feeling did not resolve by escaping from it but worsened by living with an addicted husband.

“... to escape living with my father and brothers and their harassment, I married a man who was beating me from the beginning so that I got injured to the death and fainted. He did not understand that I am a human and not supposed to pay for his sins. If I died under his kicks, no one would give me a hand. I was afraid of him. I always thought death was near me, and when I got pregnant, he was always out with his friends until night. He was not even home for some nights. He did not know himself responsible for anything in life. Sometimes he came home being kicked out and in blood. Every day I blamed myself for being pregnant endangering myself as well as my baby” (Participant No. 13).

Stuck in a dilemma

Most participants said that they were wandering between belief in failure/disability and hoping at success/ability. They thought that having an addicted husband would transfer them the feeling of failure and disability, and they were looking for a way to regain hope:

“... my life is an absolute mess. I can’t go on. I’m lost. I don’t like working. I have a carpet at home to weave, but I can’t work anymore. I’ve no motivation to work. Feel fatigued and heartbroken. But if a way appears or a class to start again and somebody takes my hand. No one listens to me, as if I do not exist” (Participant No. 1).

Mirage

Most of the participants lived in broken families and now believed that because of their adverse life events, including their husbands’ addiction, they received pessimistic views from others and themselves.

“... others have a terrible notion about me. They are cynical. When I walk out, my neighbors and family ask where you were and where you went. I don’t like to go out anymore. I used to be in meetings and among other people a lot, but now I don’t want to. Everyone wants to know about my life” (Participant No. 14).

Illusion and fantasy

The illusion of loving and being loved by the husbands suffered these women. All of them believed that they were being loved.

“... my husband loved me. Maybe he loved me. Perhaps I was dreaming. Always an absurd thought is choking me; a lump in the throat, which I could never believe. Because he betrayed me, he said you are not like others. He humiliated me. That made me lose my life, and I lost” (Participant No. 9).

The third category (Hope for empowerment)

Believing in and ultimately doing some behaviors representing such expressions as “I can’t do”, “I don’t know”, and “I’m tired” are phrases mostly heard from the participants. They described their experiences of self-efficacy and self-esteem in the course of living with an addicted person as “from despair to hope”, “living in the shadow”, “fighting without a weapon”, and “bright midnights”.

From despair to hope

The vast majority of participants believed that hope and children were the only reasons they continue to live:

“... all my life are my kids. There is nothing left for me to think about myself. Things are messed up. I’m just delighted with my kids, hoping they won’t become like their father” (Participant No. 17).

Living in the shadow

In the words of the participants, the days passing by women were foggy and misty because their living environment was on the outskirts of the city, and there were no suitable facilities for them.

“... my brothers were addicted there. People were consuming drugs together. Perhaps a normal action! I accepted that I had to give up in this situation” (Participant No. 10).

Fighting without a weapon

The participants rarely believed that because of having an addicted husband, they are fighting against the challenges of life with no confidence and sense of worthiness.

“... after I worked hard from morning till night to provide a home for the family, my husband and his family tried to take home from me. However, I built it with my life. Now I destroy it myself again, even though the pressures on me are too much, and there are lots of ‘I can’ts’ in my head” (Participant No. 11).

Bright midnights

Most of the participants believed that their good days are gone and whenever they remember them, they feel happy. They thought that despite all fears and troubles of life, a star is shining in the dark.

“... my good days were when my kids were born. We had no fun and still don’t. But when I remember my mom, good childhood days that passed by without difficulties, those days were the best days of my life [crying], I wish those days would come back” (Participant No. 2).

The fourth category (Silent victim)

There was a fire in the eyes and hearts of the wives of addicted men, which suppressed because of severe personal, family, and social vulnerabilities. In the meantime, the participants used “false stars”, “sad birth”, “inner turmoil”, and “crossing the whirlpool” to acknowledge their inefficiency, inadequacy, and low self-esteem in the process of their husband’s addiction.

False stars

The participants analogized their early life with their husbands, a dream man, to a false, dark star like a prince riding a horse.

“... When I saw him, I felt like he was the man for whom I was always waiting. He was the only person who could make me happy, and I felt I was the most beautiful woman on earth. But as the days passed by, I could see the warm days substituting by the cold smoke that darkened my whole life” (Participant No. 16).

Sad birth

Every day, the participants were thinking about the cause of their birth. They often complained about coming into a world that had nothing but constant cries of pain and agony. They consider their inefficiency in their very existence, that means their being born to this world and that feeling made the conditions worse for them every day.

“… I’m always crying. I’m depressed. I don’t want to talk to anyone. It hurts to see people. I wish I hadn’t been born. My mom gave birth to my misery. I hate life. I hate working. I can’t do anything” (Participant No. 12).

Inner turmoil

The participants expressed their indescribable aches and pains in the chaos of their lives and talked about their wishes and longing for prosperity in their lives.

“… my husband’s addiction and his behavior made me mentally ill. I feel jealous of people’s lives. Even my family doesn’t care about me. Because I’m so weak. Beside anyone I sit, he will go and leave away. To everyone, I say hello, he thinks it’s for money. I hate this world and the constantly saying of “why me” bothers me from inside” (Participant No. 7).

Crossing the whirlpool

The participants believed that inaccurate information about life issues, along with an addicted husband, swallowed them like a whirlpool.

“... I did not want to get married. But I got married at my father’s insistence that first the elder sis and then the younger one. I became a miserable person because of my sister. Because he was an addict. But I didn’t know what addiction was. Later, I gave birth to a baby. Because I didn’t know how to prevent it and they told me a child might make your husband act wisely. But it didn’t. Things got worse” (Participant No. 20).

The present study indicated that almost all participants in this study reported a low level of self-efficacy and a sense of worthlessness in living with an addicted husband. They expressed their feelings by terms such as “glass roof”, “from injury to relief”, “hope for empowerment”, and “silent victim”. One of the main categories in this study describes participants’ living with addicted husband as a glass roof (with subcategories of glass support, discredited, soulless scarecrow, and shame).

In this regard, Mahdizadeh, et al. study reports that addicted householders are not capable of fulfilling their roles as husbands and fathers; therefore, the role of women in such families becomes more vital [22]. Also in the study of Razzaghi et al., disruption of spousal and paternal roles and mutual expectations about rights and duties of family members (due to addiction), affect man’s authority, dignity, and his status in the family [23]. So, if a man fails to take his rightful place at home which is at the head of family, he will respond to this failure by abusing his wife and children [24]. According to the study participants, their husbands’ addiction has brought them emotional distress, contention, conflict, and shame.

Another main category is “from injury to relief” which includes subcategories of “feeling of insecurity in the past and present”, “stuck in a dilemma”, “mirages and fantasies” about self-efficacy and self-esteem. Other studies have reported similar results [25-27]. These studies confirm the feeling of insecurity among the participants in this study that is evident in the low self-efficacy and self-esteem of the women participating in the study. One of the concepts discussed in Fathi study was the negative attitude of the community towards these women [28]. This attitude may be due to the labeling; the labeled person may accept the role attributed to her. Besides, the results of Mancheri study show that addiction affects the mental health of family members [29]. In this study, women who may face these challenges because of their husband’s drug addiction may feel inefficient and worthless. The results of the present study support the term “mirage” extracted from the concepts in the subcategories and emphasize that a person with a negative label, suffers more from a sense of worthlessness and inefficiency.

The other main category found in the research is “hope for empowerment”, which includes several subcategories. Similarly, Joolaei study has shown that wives of the addicted husbands, as the most vulnerable members in the family, face numerous consequences of addiction, including hopelessness, improper living environments, and a sense of worthlessness [30]. The results of the Moriarty study indicate a decrease in self-confidence, social and behavioral isolation, social problems, financial pressures, and fear and anxiety in other family members, especially the women [31]. The findings of this study show that hopelessness and fear lead to inefficiency and low self-esteem in women.

Finally, there is the main category of “silent victim”, which included several subcategories of “false stars”, “sad birth”, “inner turmoil”, and “crossing the whirlpool”. The findings of the present study support the conclusions of Noori study reporting that self-harm behaviors, depression, anxiety, and aggressive reactions could be observed among all of the participants and all of these items have been effective on psychological indicators of self-efficacy and self-esteem [9]. Many disorders and injuries are rooted in the inability of individuals to properly analyze their problems, lack of control, inadequacy to deal with difficult situations, and lack of readiness to solve living issues and challenges in an appropriate manner [32, 33]. Quite the same situation was observed in wives of addicted husbands who were experiencing a significant lack of self-efficacy and self-esteem.

The point is that all these challenges provide a significant backdrop to women’s problems and threaten their physical and mental health, while these women expressed their hope to become stronger and able to overcome barriers and obstacles as essential factors in regaining their self-esteem and self-efficacy. Therefore, providing educational and counseling services for these women is valuable and vital.

The common point of the previous studies and the present one is that expressing one’s experiences, as well as the other people’s support, is crucial to facilitate mental health, including self-efficacy and self-esteem [34]. Holding motivational training and counseling sessions can be motivating for these women. Education can promote women’s mental health and self-esteem, help them to gain experience, problem-solving skill, and effective communication that would prevent negative behaviors. Also, there are a set of abilities and skills that enable one to effectively deal with stresses caused by exposure to stressful stimuli. Considering that addiction is a significant risk factor for violence against women and their sense of inadequacy and lack of self-esteem, mental health policies should consider preventive programs to stop violence and its consequences [35].

In this study, the participants mentioned behaviors such as fear, insecurity, mistrust, hopelessness, lack of responsibility in living with an addicted husband. However, the impact of drug addiction of the husbands on their wives is still unclear and hidden from the others. Families and society must understand the prominent role of women in society. In this regard, the most crucial step that can be taken is to understand the needs and feelings of such women to empower them in the fields of education, health, and employment. In this endeavor, the distinguished and prominent people of the society should provide the necessary support.

Wives with addicted husbands need special support, understanding of their conditions, and assistance to improve and manage their lives. Since women play an essential role in shaping the family, attention to them, and their problems seem critical. It is recommended that they are provided sufficient awareness of their psychiatric conditions concerning their husbands’ addiction. Also, they should be assisted with some special supports in terms of education, counseling, referral to specialized centers for vulnerable women, and social support sites to address their complex situation and by using training programs, to enhance their health conditions.

The findings of this study should help authorities to plan and provide the best possible psychological and psychiatric counseling and treatment programs for relieving physical, mental, and social problems of these women.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Ethical principles in the study included obtaining written informed consent from all participants, recording interviews anonymously and confidentially, ensuring confidentiality of the information, and their right to go on or exit from the project. The Research Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved the study (Code of ethics: 395412).

Funding

The present paper was extracted from the MSc thesis of the first author in Midwifery (No. 395412), School of nursing and midwifery approved by the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Another main category is “from injury to relief” which includes subcategories of “feeling of insecurity in the past and present”, “stuck in a dilemma”, “mirages and fantasies” about self-efficacy and self-esteem. Other studies have reported similar results [25-27]. These studies confirm the feeling of insecurity among the participants in this study that is evident in the low self-efficacy and self-esteem of the women participating in the study. One of the concepts discussed in Fathi study was the negative attitude of the community towards these women [28]. This attitude may be due to the labeling; the labeled person may accept the role attributed to her. Besides, the results of Mancheri study show that addiction affects the mental health of family members [29]. In this study, women who may face these challenges because of their husband’s drug addiction may feel inefficient and worthless. The results of the present study support the term “mirage” extracted from the concepts in the subcategories and emphasize that a person with a negative label, suffers more from a sense of worthlessness and inefficiency.

The other main category found in the research is “hope for empowerment”, which includes several subcategories. Similarly, Joolaei study has shown that wives of the addicted husbands, as the most vulnerable members in the family, face numerous consequences of addiction, including hopelessness, improper living environments, and a sense of worthlessness [30]. The results of the Moriarty study indicate a decrease in self-confidence, social and behavioral isolation, social problems, financial pressures, and fear and anxiety in other family members, especially the women [31]. The findings of this study show that hopelessness and fear lead to inefficiency and low self-esteem in women.

Finally, there is the main category of “silent victim”, which included several subcategories of “false stars”, “sad birth”, “inner turmoil”, and “crossing the whirlpool”. The findings of the present study support the conclusions of Noori study reporting that self-harm behaviors, depression, anxiety, and aggressive reactions could be observed among all of the participants and all of these items have been effective on psychological indicators of self-efficacy and self-esteem [9]. Many disorders and injuries are rooted in the inability of individuals to properly analyze their problems, lack of control, inadequacy to deal with difficult situations, and lack of readiness to solve living issues and challenges in an appropriate manner [32, 33]. Quite the same situation was observed in wives of addicted husbands who were experiencing a significant lack of self-efficacy and self-esteem.

The point is that all these challenges provide a significant backdrop to women’s problems and threaten their physical and mental health, while these women expressed their hope to become stronger and able to overcome barriers and obstacles as essential factors in regaining their self-esteem and self-efficacy. Therefore, providing educational and counseling services for these women is valuable and vital.

The common point of the previous studies and the present one is that expressing one’s experiences, as well as the other people’s support, is crucial to facilitate mental health, including self-efficacy and self-esteem [34]. Holding motivational training and counseling sessions can be motivating for these women. Education can promote women’s mental health and self-esteem, help them to gain experience, problem-solving skill, and effective communication that would prevent negative behaviors. Also, there are a set of abilities and skills that enable one to effectively deal with stresses caused by exposure to stressful stimuli. Considering that addiction is a significant risk factor for violence against women and their sense of inadequacy and lack of self-esteem, mental health policies should consider preventive programs to stop violence and its consequences [35].

In this study, the participants mentioned behaviors such as fear, insecurity, mistrust, hopelessness, lack of responsibility in living with an addicted husband. However, the impact of drug addiction of the husbands on their wives is still unclear and hidden from the others. Families and society must understand the prominent role of women in society. In this regard, the most crucial step that can be taken is to understand the needs and feelings of such women to empower them in the fields of education, health, and employment. In this endeavor, the distinguished and prominent people of the society should provide the necessary support.

Wives with addicted husbands need special support, understanding of their conditions, and assistance to improve and manage their lives. Since women play an essential role in shaping the family, attention to them, and their problems seem critical. It is recommended that they are provided sufficient awareness of their psychiatric conditions concerning their husbands’ addiction. Also, they should be assisted with some special supports in terms of education, counseling, referral to specialized centers for vulnerable women, and social support sites to address their complex situation and by using training programs, to enhance their health conditions.

The findings of this study should help authorities to plan and provide the best possible psychological and psychiatric counseling and treatment programs for relieving physical, mental, and social problems of these women.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Ethical principles in the study included obtaining written informed consent from all participants, recording interviews anonymously and confidentially, ensuring confidentiality of the information, and their right to go on or exit from the project. The Research Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved the study (Code of ethics: 395412).

Funding

The present paper was extracted from the MSc thesis of the first author in Midwifery (No. 395412), School of nursing and midwifery approved by the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors contributions

All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975-2008. Maryland: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010.

- DiClemente CC. Addiction and change: How addictions develop and addicted people recover. New York: Guilford Press; 2018.

- Rafiee H, Sajadi H, Narenjiha H, Nouri R. [Inter-disciplinary research methods and problems of addiction and other social deviations (Persian)]. Tehran: Danzheh; 2008.

- Niaz K, Pietchman T, Davis P, Carpentier C, Raithelhuber M. World drug report 2017 [Internet]. 2017 [Last Access: 2019 September 2]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2017/en/exsum.html

- Euronews. [Official statistics of drug users in iran two million and eight hundred thousand (Persian)] [Internet]. 2018 [Updated 2018 June 19]. Available from: https://fa.euronews.com/2018/06/19/official-statistics-of-drug-users-in-iran-two-million-and-eight-hundred-thousand

- Hrušková M, Mrhálek T. Risky behaviour in older school children. Kontakt. 2018; 20(1):e81-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.kontakt.2017.11.001]

- Ray GT, Mertens JR, Weisner C. Family members of people with alcohol or drug dependence: Health problems and medical cost compared to family members of people with diabetes and asthma. Addiction. 2009; 104(2):203-14 [DOI:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02447.x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rahgozar H, Mohammadi A, Yousefi S, Piran P. The impact of father’s addiction on his supportive and economic role in the family and social relations and socialization of the family members: The case of Shiraz, Iran. Asian Social Science. 2012; 8(2):27-33. [DOI:10.5539/ass.v8n2p27]

- Noori R, Jafari F, Moazen B, Vishteh HR, Farhoudian A, Narenjiha H, et al. Evaluation of anxiety and depression among female spouses of Iranian male drug dependents. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors & Addiction. 2015; 4(1):1-6. [DOI:10.5812/ijhrba.21624] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hitchens K. All rights resered addiction is a family problem: The process of addiction for families. Journal of Primary Health Care. 2011; 6(2):12-7.

- Statham DJ, Connor JP, Kavanagh DJ, Feeney GF, Young RM, May J, et al. Measuring alcohol craving: Development of the alcohol craving experience questionnaire. Addiction. 2011; 106(7):1230-8 [DOI:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03442.x] [PMID]

- Hajihasani ME, Shafi Abadi A, Pirsaghi FA, Kiyanipour OM. [Relationship between aggression, assertiveness, depression and addiction potential in female students of Allameh Tabbatabai (Persian)]. Knowledge & Research in Applied Psychology. 2012; 13(3):65-74.

- Satyanarayana VA, Nattala P, Selvam S, Pradeep J, Hebbani S, Hegde S, et al. Integrated cognitive behavioral intervention reduces intimate partner violence among alcohol dependent men, and improves mental health outcomes in their spouses: A clinic based randomized controlled trial from South India. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2016; 64:29-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsat.2016.02.005] [PMID]

- McGilloway A, Hall RE, Lee T, Bhui KS. A systematic review of personality disorder, race and ethnicity: Prevalence, aetiology and treatment. BMC Psychiatry. 2010; 10:33. [DOI:10.1186/1471-244X-10-33] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zarshenas L, Baneshi M, Sharif F, Sarani EM. Anger management in substance abuse based on cognitive behavioral therapy: An interventional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017; 17:375. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-017-1511-z] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Chambers C, Chiu S, Scott AN, Tolomiczenko G, Redelmeier DA, Levinson W, et al. Factors associated with poor mental health status among homeless women with and without dependent children. Community Mental Health Journal. 2014; 50(5):553-9 [DOI:10.1007/s10597-013-9605-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Najafi K, Zarrabi H, Kafi M, Nazifi F. [Compare the quality of life of spouses of addicted men with a control group (Persian)]. Journal of Guilan University of Medical Sciences. 2005; 14(55):35-41.

- Moriarty H, Stubbe M, Bradford S, Tapper S, Lim BT. Exploring resilience in families living with addiction. Journal of Primary Health Care. 2011; 3(3):210-7. [DOI:10.1071/HC11210] [PMID]

- Lee KM, Manning V, Teoh HC, Winslow M, Lee A, Subramaniam M, et al. Stress‐coping morbidity among family members of addiction patients in Singapore. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011; 30(4):441-7. [DOI:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00301.x] [PMID]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005; 15(9):1277-88. [DOI:10.1177/1049732305276687] [PMID]

- Roberts P, Priest H. Reliability and validity in research. Nursing Standard. 2006; 20(44):41-5. [DOI:10.7748/ns2006.07.20.44.41.c6560]

- Mahdizadeh S, Ghoddoosi A, Naji SA. [Investigation of internal tensions of wives of men whom addicted to heroin (Persian)]. Alborz University Medical Journal. 2013; 2(3):128-38.

- Razaghi N, Ramezani M, Tabatabaye Nejad M, Parvizi S. [Social cultural background of domestic violence against women in Mashhad: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. 2013; 17(8):519-9.

- Siapoush A , Ajam Dashtinezhad F. [A study on the effective socio-economic factors of violence against women in Ahvas (Persian)]. The Sociology of the Youth Studies. 2009; 1(3):91-120.

- Mohammad Khani P. The dimensions of personal-communication problems of widowed wives: Perspective on rehabilitation program for widows afflicted with addiction. Journal of Research in Addiction Research. 2009; 3(9):17-36.

- Sen S, Bolsoy N. Violence against women: Prevalence and risk factors in Turkish sample. BMC Women’s Health. 2017; 17(1):100. [DOI:10.1186/s12905-017-0454-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Heise L. Violence against women: The missing agenda. In: Gay J, editor. The Health of Women. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [DOI:10.4324/9780429496455-9]

- Fathi A. Musavi Far B. [Exploring the experiences of addicts regarding social and family supports as facilitators to addiction abstinence: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Research on Addiction. 2016; 10(38):119-36.

- Mancheri H, Sharifi Neyestanak ND, Seyedfatemi N, Heydari M, Ghodoosi M. [Psychosocial problems of families living with an addicted family member (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Nursing. 2013; 26(83):48-56.

- Joolaei S, Fereidooni Z, Fatemi NS, Meshkibaf MH, Mirlashri J. Exploring needs and expectations of spouses of addicted men in Iran: A qualitative study. Global Journal of Health Science. 2014; 6(5):132-41. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v6n5p132] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Moriarty H, Stubbe M. Exploring resilience in families living with addiction. Journal of Primary Health Care. 2011; 3(3):210-7. [DOI:10.1071/HC11210] [PMID]

- Rahimi Movaghar A, Malayerikhah Langroodi Z, Delbarpour Ahmadi S, Amin Esmaeili M. [A qualitative study of specific needs of women for treatment of addiction (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2011; 17(2):116-25.

- Kiss L, Schraiber LB, Heise L, Zimmerman C, Gouveia N, Watts C. Gender-based violence andsocioeconomic inequalities: Does living in more deprived neighbourhoods increase women’s risk of intimatepartner violence? Social Science & Medicine. 2012; 74(8):1172-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.033] [PMID]

- Rodriguez N, Griffin ML. Gender differences in drug market activities: A comparative analysis of men and womens participation in the drug market. Arizona: Arizona State University; 2005.

- Rahnavardi M, Ahmadi Dolabi M, Kiani M, Pur Hoseyn Gholi A, Shayan A. Comparing husbands’ addiction in women with and without exposure to domestic violence. Journal of Holistic Nursing and Midwifery. 2018; 28(4):231-8. [DOI:10.29252/hnmj.28.4.231]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2019/08/2 | Accepted: 2019/09/10 | Published: 2019/10/1

Received: 2019/08/2 | Accepted: 2019/09/10 | Published: 2019/10/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |