Thu, Apr 25, 2024

Volume 29, Issue 1 (1-2019)

JHNM 2019, 29(1): 43-49 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nourani S, Seraj F, Shakeri M T, Mokhber N. The Relationship Between Gender-Role Beliefs, Household Labor Division and Marital Satisfaction in Couples. JHNM 2019; 29 (1) :43-49

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-875-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-875-en.html

1- Instructor, Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

2- Midwifery (MSc.), Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. , serajf901@mums.ac.ir

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Social Medicine, School of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

4- Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatric, School of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

2- Midwifery (MSc.), Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. , serajf901@mums.ac.ir

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Social Medicine, School of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

4- Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatric, School of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 503 kb]

(1443 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4622 Views)

According to our study results, there is no significant relationship between the participation of women in housework and their marital satisfaction. This is in agreement with the results of Ghobadi and Dehghani [18], Frisco and Williams [32], and Greenstein [33] studies, but is not consistent with the findings of Oshio [10], Toth [11], McGovern [24], and Moller and Hwang [31]. Perhaps the reason for this discrepancy, is related to the conditions of transition to parenthood. These studies did not study the women with infant children. Only Moller and Hwang [31] reported a significant correlation between experiences of household workload and the quality of couple relationship for women when they had both their first and their second child.

In the current study, marital satisfaction of women was higher when their husband performed more household tasks. This is consistent with the findings of Moller and Hwang [31] and Tsuya and Bumpass [34] studies. Tsuya and Bumpass in their study in Japan found out that marriage dramatically increased women’s housework time but produced little change in men’s time. In addition, husbands’ housework hours were positively correlated with reported marital satisfaction of both spouses. However, this result is not in agreement with the results of Ghobadi and Dehghani [18] and Polachek [22] studies. According to them, the division of housework is not effective on marital satisfaction of couples, and its perceived fairness has positive correlation with marital relationship and negative relationship with marital conflicts.

In our study, the type of gender-role beliefs in couples was not significantly correlated with the division of household labor. This is not in agreement with the results of McGovern study [24]. In that study, couples’ sex-role beliefs had statistically significant relationship with the division of household tasks. That is, couples with traditional attitudes completed housework tasks traditionally; those with a modern attitude shared tasks equally. Perhaps, cultural issues that govern the community affect the division of household tasks.

The present study was carried out in couples with infants who were in transition to parenthood. That is, when women have babies, they knowingly accept most of their household tasks. In this situation, there are the needs of a newborn baby like breastfeeding and caring on the one hand and economic needs of the family on the other hand. After the delivery and considering the difference in income levels between men and women, the husband prefers to have a breadwinner role and the wife to stay home and do the housework.

According to Katz-Wise, because of the effect of transition to parenthood on gender-role attitudes of couples, the traditional attitudes are observed during this period [30]. In first-time women, the traditional attitudes return to the egalitarian beliefs over time, and because of inexperience and unpreparedness in managing tasks, they become confused. However, in second-time women, the traditional attitude is stable and husband’s participation is not related to marital satisfaction.

Consistent with the findings of Ghobadi and Dehghani [18], McGovern [24], and Stanik and Bryant [35] studies, we found no statistically significant relationship between gender-role beliefs and marital satisfaction of couples. Stanik and Bryant reported that couples had lower marital quality when husbands had relatively more traditional gender role attitudes. Husbands reported lower marital quality when the couple engaged in a relatively more traditional division of household labor, while husbands with more traditional attitudes who also engaged in a traditional division of labor reported lower marital quality compared to other husbands. This inconsistency is probably due to differences in the research samples. Stanik and Bryant evaluated newlywed couples, while we assessed couples with children.

Another reason is the difference in the used assessment tools. McGovern reported that modern husbands had greater marital adjustment than traditional husbands, but the attitudes of wives had no relationship with their marital adjustment. Lachance-Grzela suggested that emotional rewards the mothers receive from their romantic partner influence the way they use gender ideology to evaluate the fairness of the division of family labor in their household [23].

Their results indicate that egalitarian gender ideology is associated with a greater sense of unfairness only when women feel that their partner demonstrates a low level of appreciation toward them. When women with traditional gender ideology feel that their partners demonstrate a low level of appreciation toward them, they perceive that the housework is fair, but when they feel that their partners respect, appreciate, and care for them, egalitarian gender role attitudes are not associated with a perception of unfairness, and is more likely as fair division of household labor [23]. Perhaps it is thought that if both couples have same traditional/modern beliefs and attitudes, they will have more marital satisfaction or vice versa, but the fact is that if they have different attitudes, they can have more marital adjustment [24].

One of the advantages of this study is that it examined both spouses because in most studies only one of the couples completed questionnaires. Low sample size and survey of urban couples with children were the limitations of this study. In urban communities, couples have more access to modern appliances for housework such as washing machines and vacuum cleaners, though the family’s financial status influences their access to these modern appliances. Another limitation of this study was that it did not examine working women or housewives separately and couples were not divided into those with no children, first-time parents, second-time parents, etc. Further studies are recommended with larger sample size on working women, housewives, couples with children, and childless parents in urban and rural communities.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved of the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (Code: 920690).

Funding

This paper was extracted from a master thesis of Fatemeh Seraj in midwifery approved in the Research Council the faculty of nursing and midwifery of Mashhad University ofmedical sciences.

Authors contributions

The authors contributions is as follows: Conceptualization: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Methodology: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Investigation: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Writing-original draft: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Writing-review & editing: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Funding acquisition:sFatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Resources: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; and Supervision: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank for the financial support of Research Deputy, and the cooperation of Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery.

References

Full-Text: (2126 Views)

Introduction

Satisfactory marital relationship is an indicator of positive family function that directly or indirectly facilitates effective parenting, improves the relationships of children with each other and with their parents, and increases children’s the adaptability [1]. Marital satisfaction has been defined as an objective feeling of satisfaction and pleasure experienced by the husband or wife while considering all aspects of life. It is important in various aspects, including the individual and mental health of children, mental health of husband and wife, family health and of course prevention of various physical and mental illnesses [2, 3].

Marital conflicts, in addition to marital dissatisfaction, create an inappropriate environment for the growth and development of children and consequently social harms [4]. Marital satisfaction helps the individual’s overall adaptability and creates more self-esteem and consistency in social relationships [5]. Adaptable people whose marriage are stable generally live longer, are physically healthier and happier, and have less psychological problems [6]. Marital satisfaction is affected by some factors such as personality traits, conflict resolution, family income, duration of marriage, infertility, wife’s education, husband/wife’s occupation, and planned pregnancy [7, 8].

Overall, the main factors affecting marital satisfaction can be categorized into three groups: 1. Intrapersonal factors such as personality traits and individual habits, expectations, ideals, and values; 2. Interpersonal factors such as relationship rules, conflict resolution, sex, interpersonal commitment and rules, and, the division of household labor; and 3. External factors such as relationships with relatives/children/parents/friends, and financial issues [9].

The division of household labor if not agreed upon couples, can lead to their dissatisfaction and if agreed, can increase marital satisfaction and promote their mental health. Couples’ beliefs about the division of household labor are different, and as a result, the degree of their participation in these tasks as an objective and behavioral aspect of perceived justice can have a direct effect on marital satisfaction [10-12]. The employment of women outside the home in paid jobs was the beginning of questioning the fairness of dividing household tasks between husband and wife, and then housekeeping tasks of women were considered as tedious, erosive, and undesirable activities. In other words, increasing the participation of women in the labor force and paid works in industrial societies is a key variable in the concept of the division of household labor [13-17].

There are three perspectives on division of household labor between couples: relative resource theory, time constraints, and gender ideology about the division of family work [10]. Various studies have investigated the fairness of the division of household labor and quality of marital relationships using these approaches. For example, a study used relative resource theory to evaluate quality of marital relationships, and suggested that individuals with higher levels of education have higher marital stability [18-20]. According to time constraints, when husbands and wives spend more time in paid work, they have less time to spend performing household labor. This condition may put pressure on them and reduce marital satisfaction.

Faulkner found out that in the US, marital satisfaction decreases with increased time spent in housework [21]. In the study of Polachek, results indicated that time spent for housework was harmful for mental and physical health of couples when it interferes with weekends relax or when individuals feel that the division of housework is unfair [22]. Lachance-Grzela found out that gender ideology of women affects their perceived fairness of the division of family labor in the household [23]. McGovern reported that spouses had greater marital adjustment when husbands completed traditionally male household labor, but when spouses completed male labor, it had no effect on marital adjustment of husbands [24].

Although some studies have shown that modern gender-role beliefs may have a negative effect on marital satisfaction of women [24], the similarity or differences in these beliefs between couples is more important than their support of traditional or modern beliefs. It means that wives probably have less satisfaction when their beliefs are different from those of their husbands [25]. People with traditional beliefs believe that women should stay at home and be responsible for housework and child care, but people with modern beliefs expect that both husband and wife can have paid works and housekeeping tasks should be equally divided between them [18, 24, 26].

In Iran, few studies have been conducted on the relationship between the division of household labor and marital satisfaction and the beliefs of each spouse in the division of housework. In this regard and considering the importance of marital satisfaction, especially in couples having babies, this study attempts to investigate the association between gender-role beliefs, household labor division and marital satisfaction in couples referred to health care centers in Mashhad City, Iran.

Materials and Methods

This is an analytical study with correlational design conducted on 120 couples having infant children. Sampling was conducted in three phases of stratifying, clustering, and convenience in health care centers located in Mashhad, Iran in 2013. The samples were selected from the study population consisted of all couples with infant children referred to 14 health care centers in Mashhad (n=200). At first the five health centers, according to the division policy of health centers in Mashhad, were selected as strata. Then, according to the population covered by each, the centers providing health services were randomly selected as clusters. Then those who were eligible to enter the study were selected using convenience sampling technique.

Considering the correlation coefficient of 0.7 between the two variables of marital satisfaction and participation in household labor obtained from the preliminary study, the sample size for examining the variables of marital satisfaction and household labor division was calculated as 20, and for examining gender-role beliefs, as 19. Given test power as 80% and significant level of 0.05, the total sample size was 120.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: having literacy, living with wife/husband at the time of study, lacking mental and physical illness (self-report), not having twins or multiple children, lacking history of drug abuse or alcohol consumption, having a healthy baby who is not adopted, and having signed the informed consent form. Returning incomplete questionnaires results in exclusion from the study. The data collection tools were a demographic form, Persian version of ENRICH (Evaluation and Nurturing Relationship Issues, Communication, and Happiness) marital satisfaction scale, a researcher-designed Household Labor Division (HLD) questionnaire, and a researcher-designed Gender-Role Belief (GRB) questionnaire.

ENRICH was developed by Fowers and Olson [27]. It has 47 items with 12 subscales rated based on 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=moderately disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=moderately agree, 5=strongly agree). Items 4, 6, 8, 11-16, 18-24, 30-33, 37-42, and 45-47 have reverse scoring. Scores 47-84 indicate very low Marital Satisfaction (MS); 85-122 low MS; 123-160 moderate MS; 161-198 high MS; and 199-235 indicates very high level of MS between couples [27, 28]. In the present study, the ENRICH reliability was calculated with Cronbach alpha as 0.78.

HLD was designed in Persian based on Ghobadi and Dehghani [18] designed tool and other tools such as Krause Household Task scale according to the Iranian culture [10, 11, 18, 29]. To determine the content validity of the questionnaire, 10 faculty members of the midwifery department and 3 faculty members of sociology Department reviewed and modified it. HLD has 15 items which assess the level of participation in the housework tasks scored based on 5-point Likert-type scale (1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often, 5=always). The total score ranges from 15 to 75 and divided into three levels: 15-34 indicates low participation; 35-54 shows moderate participation, and 55-75 indicates high participation in division of household labor. Its reliability with Cronbach alpha was obtained as 0.75.

GRB was designed in Persian according to a similar questionnaire by Ghobadi and Dehghani [18], Osmond-Martin Sex Role Attitude Scale (Osmond & Martin, 1975) [24], Traditional-Egalitarian Sex Role (TESR) scale [30], and Gender Role Attitude Traditionalism Scale [23]. This questionnaire assesses the gender role attitudes of couples toward household labor division. It has 15 items answered using three options: 1. Wife’s task; 2. husband’s task; and 3. Both. Options 1 and 2 has 1 point, and option 3 which indicates modern belief and scores 2 points. The total score ranges between 15 and 30 and is divided into two levels: scores 15-22 indicates traditional beliefs of couples and scores ≥23 shows modern attitude toward household labor division. To examine the content validity of the questionnaire, it was sent to 10 faculty members of the midwifery department and 3 faculty members of sociology department, and after modifications, its validity was verified. Its reliability with Cronbach alpha was obtained as 0.81.

After obtaining a Letter of Permission from the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of the university and its Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, as well as receiving permission from the health centers, the researcher referred to these centers every morning in the office hours for collecting data after introducing himself, giving details about the research objectives to the couples, assuring them about the confidentiality of their information, and obtaining their written informed consent. The couples were asked to complete the questionnaires independently and deliver them to the researcher separately. The time required to complete the questionnaires was about 30 minutes.

After collecting data, they were analyzed in SPSS V. 16 using descriptive (mean, standard deviation) and inferential statistics (the Spearman correlation test). In addition, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the normality of data distribution. P<0.05 was considered the significant level for all tests.

Results

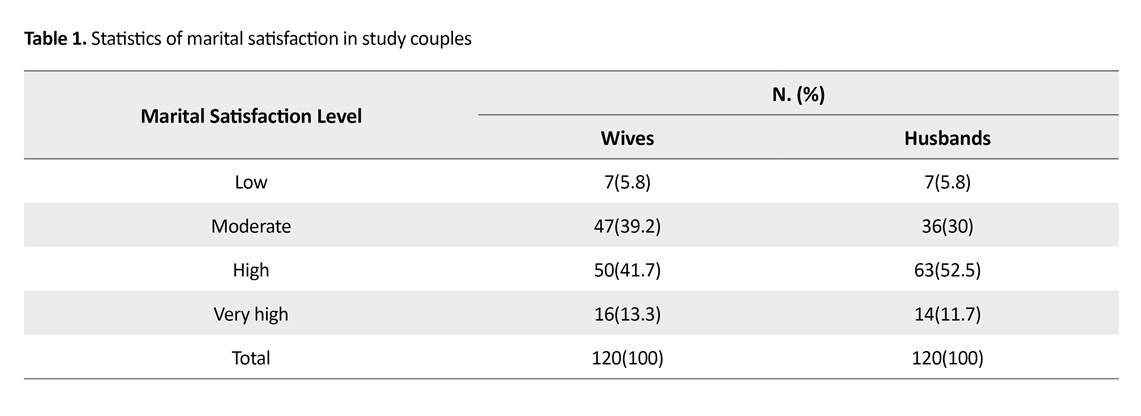

The age of the female samples ranged between 16 and 43 years (30±5.28), and the age of male samples ranged between 21 and 52 years (33±51). A total of 75 (62.5%) wives and 64 (53.3%) husbands had academic education. Also, 65 (54.2%) wives had modern beliefs and 55 (45.8%) traditional beliefs, while 50 (41.7%) husbands had modern beliefs and 70 (58.3%) traditional beliefs. In 41 (34.16%) couples, gender-role beliefs were traditional, while in 36 (30%), the beliefs were modern and 43 (35.83%) had different gender-role beliefs (i.e. they did not agree with the beliefs of each other). Statistics about marital satisfaction of samples are presented in Table 1.

Couples’ beliefs had no significant relationship with their marital satisfaction (P=0.07 for wives, and P=0.32 for husbands). There was not a significant relationship between couples’ beliefs and their level of participation in household labor (P=0.10 for wives, and P=0.52 for husbands). In addition, couples’ agreement on gender beliefs did not show a significant relationship with their marital satisfaction.

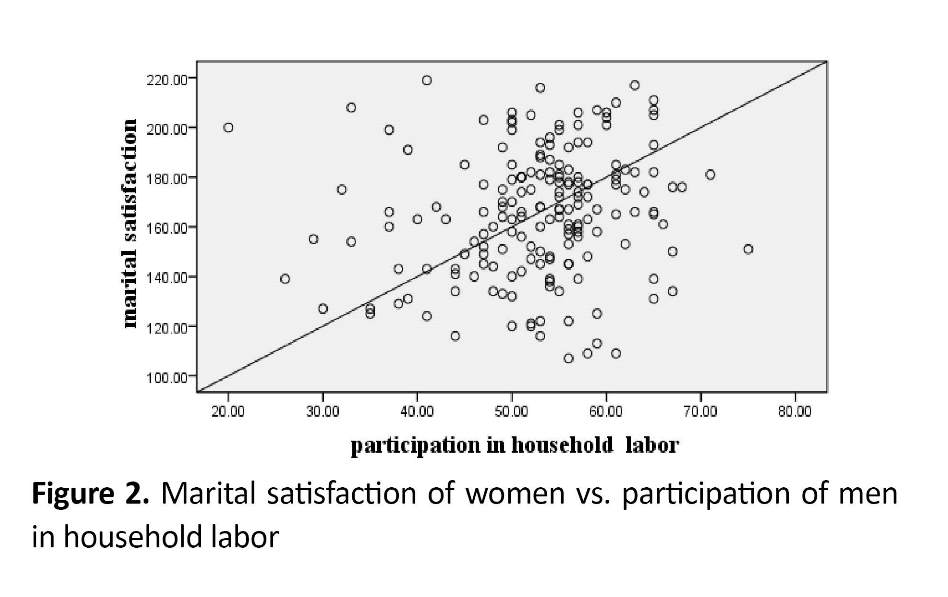

The Spearman correlation test results indicate that the participation of husbands in household labor significantly correlates to their marital satisfaction (P=0.025, r=0.204), and as their marital satisfaction increases, their participation increases, too (Figure 1). Wives’ participation has no significant relationship with their marital satisfaction (P=0.90, r=-0.01). Marital satisfaction between men and women has significant relationship with each other (P<0.55, r =0.55) such that with the increase of satisfaction in men, the marital satisfaction of women also increases. Moreover, women’s marital satisfaction increases with the increased participation of men in housework (P=0.04, r=0.18) (Figure 2).

To investigate the relationship of demographic variables with study variables, the Spearman test was used because of the qualitative distribution of data. Based on the results, husband’s income had significant association with marital satisfaction of women (P<0.05). Husband’s educational level was not associated with any of the study variables, but wife’s educational level had a statistically significant relationship with her gender-role beliefs (P<0.01) such that those with higher education had more egalitarian and modern beliefs.

The type of gender-role beliefs in wives had statistically significant association with social status of the husbands (P =0.01), i.e. women whose husbands had higher social class, had more gender equitable and modern attitudes. Wives with higher social class also reported more gender equitable and modern attitudes (P=0.001). Gender-role beliefs of wives and husbands had significant relationship with each other, i.e. women with gender equitable attitudes had husbands with similar attitudes and vice versa (P=0.002). Age of men had a statistically significant relationship with their gender-role beliefs (P=0.019), and with the increase of age, they tend to have more gender equitable and modern attitudes.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate a significant relationship between participation of men in household labor and their marital satisfaction. This is consistent with the results of Oshio [10], Toth [11], McGovern [24], and Moller and Hwang [31] studies. In these studies, different tools were used to investigate the participation of spouses in household labor, because there is no standardized tool in this area. Some of them measured the hours spent on housework and others considered the way couples divide the housework tasks. Perhaps, the reason for our study result is that, by increased marital satisfaction of men (due to affection to their wives), they get more involved in housework for the comfort of their wives.

Satisfactory marital relationship is an indicator of positive family function that directly or indirectly facilitates effective parenting, improves the relationships of children with each other and with their parents, and increases children’s the adaptability [1]. Marital satisfaction has been defined as an objective feeling of satisfaction and pleasure experienced by the husband or wife while considering all aspects of life. It is important in various aspects, including the individual and mental health of children, mental health of husband and wife, family health and of course prevention of various physical and mental illnesses [2, 3].

Marital conflicts, in addition to marital dissatisfaction, create an inappropriate environment for the growth and development of children and consequently social harms [4]. Marital satisfaction helps the individual’s overall adaptability and creates more self-esteem and consistency in social relationships [5]. Adaptable people whose marriage are stable generally live longer, are physically healthier and happier, and have less psychological problems [6]. Marital satisfaction is affected by some factors such as personality traits, conflict resolution, family income, duration of marriage, infertility, wife’s education, husband/wife’s occupation, and planned pregnancy [7, 8].

Overall, the main factors affecting marital satisfaction can be categorized into three groups: 1. Intrapersonal factors such as personality traits and individual habits, expectations, ideals, and values; 2. Interpersonal factors such as relationship rules, conflict resolution, sex, interpersonal commitment and rules, and, the division of household labor; and 3. External factors such as relationships with relatives/children/parents/friends, and financial issues [9].

The division of household labor if not agreed upon couples, can lead to their dissatisfaction and if agreed, can increase marital satisfaction and promote their mental health. Couples’ beliefs about the division of household labor are different, and as a result, the degree of their participation in these tasks as an objective and behavioral aspect of perceived justice can have a direct effect on marital satisfaction [10-12]. The employment of women outside the home in paid jobs was the beginning of questioning the fairness of dividing household tasks between husband and wife, and then housekeeping tasks of women were considered as tedious, erosive, and undesirable activities. In other words, increasing the participation of women in the labor force and paid works in industrial societies is a key variable in the concept of the division of household labor [13-17].

There are three perspectives on division of household labor between couples: relative resource theory, time constraints, and gender ideology about the division of family work [10]. Various studies have investigated the fairness of the division of household labor and quality of marital relationships using these approaches. For example, a study used relative resource theory to evaluate quality of marital relationships, and suggested that individuals with higher levels of education have higher marital stability [18-20]. According to time constraints, when husbands and wives spend more time in paid work, they have less time to spend performing household labor. This condition may put pressure on them and reduce marital satisfaction.

Faulkner found out that in the US, marital satisfaction decreases with increased time spent in housework [21]. In the study of Polachek, results indicated that time spent for housework was harmful for mental and physical health of couples when it interferes with weekends relax or when individuals feel that the division of housework is unfair [22]. Lachance-Grzela found out that gender ideology of women affects their perceived fairness of the division of family labor in the household [23]. McGovern reported that spouses had greater marital adjustment when husbands completed traditionally male household labor, but when spouses completed male labor, it had no effect on marital adjustment of husbands [24].

Although some studies have shown that modern gender-role beliefs may have a negative effect on marital satisfaction of women [24], the similarity or differences in these beliefs between couples is more important than their support of traditional or modern beliefs. It means that wives probably have less satisfaction when their beliefs are different from those of their husbands [25]. People with traditional beliefs believe that women should stay at home and be responsible for housework and child care, but people with modern beliefs expect that both husband and wife can have paid works and housekeeping tasks should be equally divided between them [18, 24, 26].

In Iran, few studies have been conducted on the relationship between the division of household labor and marital satisfaction and the beliefs of each spouse in the division of housework. In this regard and considering the importance of marital satisfaction, especially in couples having babies, this study attempts to investigate the association between gender-role beliefs, household labor division and marital satisfaction in couples referred to health care centers in Mashhad City, Iran.

Materials and Methods

This is an analytical study with correlational design conducted on 120 couples having infant children. Sampling was conducted in three phases of stratifying, clustering, and convenience in health care centers located in Mashhad, Iran in 2013. The samples were selected from the study population consisted of all couples with infant children referred to 14 health care centers in Mashhad (n=200). At first the five health centers, according to the division policy of health centers in Mashhad, were selected as strata. Then, according to the population covered by each, the centers providing health services were randomly selected as clusters. Then those who were eligible to enter the study were selected using convenience sampling technique.

Considering the correlation coefficient of 0.7 between the two variables of marital satisfaction and participation in household labor obtained from the preliminary study, the sample size for examining the variables of marital satisfaction and household labor division was calculated as 20, and for examining gender-role beliefs, as 19. Given test power as 80% and significant level of 0.05, the total sample size was 120.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: having literacy, living with wife/husband at the time of study, lacking mental and physical illness (self-report), not having twins or multiple children, lacking history of drug abuse or alcohol consumption, having a healthy baby who is not adopted, and having signed the informed consent form. Returning incomplete questionnaires results in exclusion from the study. The data collection tools were a demographic form, Persian version of ENRICH (Evaluation and Nurturing Relationship Issues, Communication, and Happiness) marital satisfaction scale, a researcher-designed Household Labor Division (HLD) questionnaire, and a researcher-designed Gender-Role Belief (GRB) questionnaire.

ENRICH was developed by Fowers and Olson [27]. It has 47 items with 12 subscales rated based on 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=moderately disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=moderately agree, 5=strongly agree). Items 4, 6, 8, 11-16, 18-24, 30-33, 37-42, and 45-47 have reverse scoring. Scores 47-84 indicate very low Marital Satisfaction (MS); 85-122 low MS; 123-160 moderate MS; 161-198 high MS; and 199-235 indicates very high level of MS between couples [27, 28]. In the present study, the ENRICH reliability was calculated with Cronbach alpha as 0.78.

HLD was designed in Persian based on Ghobadi and Dehghani [18] designed tool and other tools such as Krause Household Task scale according to the Iranian culture [10, 11, 18, 29]. To determine the content validity of the questionnaire, 10 faculty members of the midwifery department and 3 faculty members of sociology Department reviewed and modified it. HLD has 15 items which assess the level of participation in the housework tasks scored based on 5-point Likert-type scale (1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often, 5=always). The total score ranges from 15 to 75 and divided into three levels: 15-34 indicates low participation; 35-54 shows moderate participation, and 55-75 indicates high participation in division of household labor. Its reliability with Cronbach alpha was obtained as 0.75.

GRB was designed in Persian according to a similar questionnaire by Ghobadi and Dehghani [18], Osmond-Martin Sex Role Attitude Scale (Osmond & Martin, 1975) [24], Traditional-Egalitarian Sex Role (TESR) scale [30], and Gender Role Attitude Traditionalism Scale [23]. This questionnaire assesses the gender role attitudes of couples toward household labor division. It has 15 items answered using three options: 1. Wife’s task; 2. husband’s task; and 3. Both. Options 1 and 2 has 1 point, and option 3 which indicates modern belief and scores 2 points. The total score ranges between 15 and 30 and is divided into two levels: scores 15-22 indicates traditional beliefs of couples and scores ≥23 shows modern attitude toward household labor division. To examine the content validity of the questionnaire, it was sent to 10 faculty members of the midwifery department and 3 faculty members of sociology department, and after modifications, its validity was verified. Its reliability with Cronbach alpha was obtained as 0.81.

After obtaining a Letter of Permission from the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of the university and its Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, as well as receiving permission from the health centers, the researcher referred to these centers every morning in the office hours for collecting data after introducing himself, giving details about the research objectives to the couples, assuring them about the confidentiality of their information, and obtaining their written informed consent. The couples were asked to complete the questionnaires independently and deliver them to the researcher separately. The time required to complete the questionnaires was about 30 minutes.

After collecting data, they were analyzed in SPSS V. 16 using descriptive (mean, standard deviation) and inferential statistics (the Spearman correlation test). In addition, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the normality of data distribution. P<0.05 was considered the significant level for all tests.

Results

The age of the female samples ranged between 16 and 43 years (30±5.28), and the age of male samples ranged between 21 and 52 years (33±51). A total of 75 (62.5%) wives and 64 (53.3%) husbands had academic education. Also, 65 (54.2%) wives had modern beliefs and 55 (45.8%) traditional beliefs, while 50 (41.7%) husbands had modern beliefs and 70 (58.3%) traditional beliefs. In 41 (34.16%) couples, gender-role beliefs were traditional, while in 36 (30%), the beliefs were modern and 43 (35.83%) had different gender-role beliefs (i.e. they did not agree with the beliefs of each other). Statistics about marital satisfaction of samples are presented in Table 1.

Couples’ beliefs had no significant relationship with their marital satisfaction (P=0.07 for wives, and P=0.32 for husbands). There was not a significant relationship between couples’ beliefs and their level of participation in household labor (P=0.10 for wives, and P=0.52 for husbands). In addition, couples’ agreement on gender beliefs did not show a significant relationship with their marital satisfaction.

The Spearman correlation test results indicate that the participation of husbands in household labor significantly correlates to their marital satisfaction (P=0.025, r=0.204), and as their marital satisfaction increases, their participation increases, too (Figure 1). Wives’ participation has no significant relationship with their marital satisfaction (P=0.90, r=-0.01). Marital satisfaction between men and women has significant relationship with each other (P<0.55, r =0.55) such that with the increase of satisfaction in men, the marital satisfaction of women also increases. Moreover, women’s marital satisfaction increases with the increased participation of men in housework (P=0.04, r=0.18) (Figure 2).

To investigate the relationship of demographic variables with study variables, the Spearman test was used because of the qualitative distribution of data. Based on the results, husband’s income had significant association with marital satisfaction of women (P<0.05). Husband’s educational level was not associated with any of the study variables, but wife’s educational level had a statistically significant relationship with her gender-role beliefs (P<0.01) such that those with higher education had more egalitarian and modern beliefs.

The type of gender-role beliefs in wives had statistically significant association with social status of the husbands (P =0.01), i.e. women whose husbands had higher social class, had more gender equitable and modern attitudes. Wives with higher social class also reported more gender equitable and modern attitudes (P=0.001). Gender-role beliefs of wives and husbands had significant relationship with each other, i.e. women with gender equitable attitudes had husbands with similar attitudes and vice versa (P=0.002). Age of men had a statistically significant relationship with their gender-role beliefs (P=0.019), and with the increase of age, they tend to have more gender equitable and modern attitudes.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate a significant relationship between participation of men in household labor and their marital satisfaction. This is consistent with the results of Oshio [10], Toth [11], McGovern [24], and Moller and Hwang [31] studies. In these studies, different tools were used to investigate the participation of spouses in household labor, because there is no standardized tool in this area. Some of them measured the hours spent on housework and others considered the way couples divide the housework tasks. Perhaps, the reason for our study result is that, by increased marital satisfaction of men (due to affection to their wives), they get more involved in housework for the comfort of their wives.

According to our study results, there is no significant relationship between the participation of women in housework and their marital satisfaction. This is in agreement with the results of Ghobadi and Dehghani [18], Frisco and Williams [32], and Greenstein [33] studies, but is not consistent with the findings of Oshio [10], Toth [11], McGovern [24], and Moller and Hwang [31]. Perhaps the reason for this discrepancy, is related to the conditions of transition to parenthood. These studies did not study the women with infant children. Only Moller and Hwang [31] reported a significant correlation between experiences of household workload and the quality of couple relationship for women when they had both their first and their second child.

In the current study, marital satisfaction of women was higher when their husband performed more household tasks. This is consistent with the findings of Moller and Hwang [31] and Tsuya and Bumpass [34] studies. Tsuya and Bumpass in their study in Japan found out that marriage dramatically increased women’s housework time but produced little change in men’s time. In addition, husbands’ housework hours were positively correlated with reported marital satisfaction of both spouses. However, this result is not in agreement with the results of Ghobadi and Dehghani [18] and Polachek [22] studies. According to them, the division of housework is not effective on marital satisfaction of couples, and its perceived fairness has positive correlation with marital relationship and negative relationship with marital conflicts.

In our study, the type of gender-role beliefs in couples was not significantly correlated with the division of household labor. This is not in agreement with the results of McGovern study [24]. In that study, couples’ sex-role beliefs had statistically significant relationship with the division of household tasks. That is, couples with traditional attitudes completed housework tasks traditionally; those with a modern attitude shared tasks equally. Perhaps, cultural issues that govern the community affect the division of household tasks.

The present study was carried out in couples with infants who were in transition to parenthood. That is, when women have babies, they knowingly accept most of their household tasks. In this situation, there are the needs of a newborn baby like breastfeeding and caring on the one hand and economic needs of the family on the other hand. After the delivery and considering the difference in income levels between men and women, the husband prefers to have a breadwinner role and the wife to stay home and do the housework.

According to Katz-Wise, because of the effect of transition to parenthood on gender-role attitudes of couples, the traditional attitudes are observed during this period [30]. In first-time women, the traditional attitudes return to the egalitarian beliefs over time, and because of inexperience and unpreparedness in managing tasks, they become confused. However, in second-time women, the traditional attitude is stable and husband’s participation is not related to marital satisfaction.

Consistent with the findings of Ghobadi and Dehghani [18], McGovern [24], and Stanik and Bryant [35] studies, we found no statistically significant relationship between gender-role beliefs and marital satisfaction of couples. Stanik and Bryant reported that couples had lower marital quality when husbands had relatively more traditional gender role attitudes. Husbands reported lower marital quality when the couple engaged in a relatively more traditional division of household labor, while husbands with more traditional attitudes who also engaged in a traditional division of labor reported lower marital quality compared to other husbands. This inconsistency is probably due to differences in the research samples. Stanik and Bryant evaluated newlywed couples, while we assessed couples with children.

Another reason is the difference in the used assessment tools. McGovern reported that modern husbands had greater marital adjustment than traditional husbands, but the attitudes of wives had no relationship with their marital adjustment. Lachance-Grzela suggested that emotional rewards the mothers receive from their romantic partner influence the way they use gender ideology to evaluate the fairness of the division of family labor in their household [23].

Their results indicate that egalitarian gender ideology is associated with a greater sense of unfairness only when women feel that their partner demonstrates a low level of appreciation toward them. When women with traditional gender ideology feel that their partners demonstrate a low level of appreciation toward them, they perceive that the housework is fair, but when they feel that their partners respect, appreciate, and care for them, egalitarian gender role attitudes are not associated with a perception of unfairness, and is more likely as fair division of household labor [23]. Perhaps it is thought that if both couples have same traditional/modern beliefs and attitudes, they will have more marital satisfaction or vice versa, but the fact is that if they have different attitudes, they can have more marital adjustment [24].

One of the advantages of this study is that it examined both spouses because in most studies only one of the couples completed questionnaires. Low sample size and survey of urban couples with children were the limitations of this study. In urban communities, couples have more access to modern appliances for housework such as washing machines and vacuum cleaners, though the family’s financial status influences their access to these modern appliances. Another limitation of this study was that it did not examine working women or housewives separately and couples were not divided into those with no children, first-time parents, second-time parents, etc. Further studies are recommended with larger sample size on working women, housewives, couples with children, and childless parents in urban and rural communities.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved of the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (Code: 920690).

Funding

This paper was extracted from a master thesis of Fatemeh Seraj in midwifery approved in the Research Council the faculty of nursing and midwifery of Mashhad University ofmedical sciences.

Authors contributions

The authors contributions is as follows: Conceptualization: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Methodology: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Investigation: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Writing-original draft: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Writing-review & editing: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Funding acquisition:sFatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; Resources: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri; and Supervision: Fatemeh Seraj, Shahla Nourani and Mohammad Taghi Shakeri.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank for the financial support of Research Deputy, and the cooperation of Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery.

References

- Wagheiy Y, Miri M. [A survey about effective factors on the marital satisfaction in employees of two Birjand universities (Persian)]. Journal of Birjand University of Medical Sciences. 2010; 16(4):43-50.

- Askarian Omran S, Sheikholeslami F, Tabari R, Kazemnejhad Leili E, Paryad E. [Role of career factors on marital satisfaction of nurses (Persian)]. Journal of Holistic Nursing and Midwifery. 2015; 25(4):102-9.

- baneian S, parvin N, kazemian A. [Marital satisfaction of women referring to health care centers in Brojen (Persian)]. Journal of Holistic Nursing and Midwifery. 2006; 16(1):1-5.

- Shakeriyan A. [Personality role in prediction of marital adjustment (Persian)]. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Science. 2011; 16(1):16-22.

- Kluwer ES. From partnership to parenthood: A review of marital change across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2010; 2(2):105-25. [DOI:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00045.x]

- Soleymanian A. [Investigating effect of unreasonable thought on marital unsatisfaction (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Tarbiat Moddares University; 2004.

- khodakarami B, Masoumi SZ, Asadi R. [The status and marital satisfaction factors in nulliparous pregnant females attending clinics in Asadabad city during years 2015 and 2016 (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of Hamadan Nursing & Midwifery Faculty. 2017; 25(1):52-9.

- Khezri Kh. Arjmand E. [The comparison of marital satisfaction level of working and householder women and affecting factors on them in Izeh city (Persian)]. Journal of Iranian Social Development Studies. 2014; 6(4):97-105.

- Perry Jenkins M, Goldberg WE, Pierce CP, Sayer AG. Shift work, role overload, and the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007; 69(1):123-38. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00349.x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Oshio T. Division of Household Labor and Marital Satisfaction in China, Japan, and Korea [MSc. thesis]. Kunitachi: Hitotsubashi University; 2006.

- Toth K. Division of domestic labor and marital satisfaction: A cross-cultural analysis [PhD. dissertation]. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada; 2008.

- Jacobs JA, Gerson K. The time divide: Work, family, and gender inequality (The family and public policy). Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2009.

- Jackson J, Miller R, Oka M, Henry R. Gender differences in marital satisfaction: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014; 76(1):105-29. [DOI:10.1111/jomf.12077]

- Lavner JA, Karney BR, Williamson HC, Bradbury TN. Bidirectional associations between newlyweds’ marital satisfaction and marital problems over time. Family Process. 2017; 56(4):869-82. [DOI:10.1111/famp.12264]

- Newkirk K, Perry Jenkins M, Sayer A. Division of household and childcare labor and relationship conflict among low-income new parents. Journal of Sex Roles. 2017; 76(5):319-33. [DOI:10.1007/s11199-016-0604-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kubricht BC, Miller R, Yang K, Harpe J, Sandberg J. Division of household labor and marital satisfaction in China: Urban and rural comparisons. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2017; 48(2):261-74.

- Carlson MW, Hans JD. Maximizing benefits and minimizing impacts: Dual-earner couples’ perceived division of household labor decision-making process. Journal of Family Studies. 2017:1-8. [DOI:10.1080/13229400.2017.1367712]

- Ghobadi K, Dehghani M. [Division of household labor, perceived justice (fairness), and marital satisfaction (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2011; 7(2):207-22.

- Nagase N, Brinton MC. The gender division of labor and second births: Labor market institutions and fertility in Japan. Demographic Research Journal. 2017; 36:339-70. [DOI:10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.11]

- Maas MK, McDaniel BT, Feinberg ME, Jones DE. Division of labor and multiple domains of sexual satisfaction among first-time parents. Journal of Family Issues. 2018; 39(1):104-27. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X15604343]

- Faulkner RA, Davey M, Davey A. Gender-related predictors of change in marital satisfaction and marital conflict. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2005; 33(1):61-83. [DOI:10.1080/01926180590889211]

- Polachek A. Gender and the division of household labor: An analysis of the implications for mental and physical health [PhD. dissertation]. Calgary: University of Calgary; 2012.

- Lachance Grzela M. Mattering moderates the link between gender ideology and perceived fairness of the division of household labor. Interpersonal. 2012; 6(2):163-75. [DOI:10.5964/ijpr.v6i2.98]

- McGovern J, Meyers S. Relationships between sex-role attitudes, division of household tasks, and marital adjustment. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2002; 24(4):601-18. [DOI:10.1023/A:1021225313735]

- Fuller TD, Edwards JN, Vorakitphokatorn S, Sermsri S. Gender differences in the psychological well-being of married men and women: An Asian case. Sociological Quarterly. 2004; 45(2):355-78. [DOI:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2004.tb00016.x]

- Hoseni SV, Jafari N. [Lankster public health nursing: population- centered health care in the community (Persian)]. Tehran: Jameeh Negar; 2009.

- Fowers BJ, Olson DH. ENRICH marital inventory: A discriminant validity and cross‐validation assessment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1989; 15(1):65-79. [DOI:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1989.tb00777.x] [PMID]

- Saatchi M, Kamkari K, Asgarian M. [Psychological tests (Persian)]. Tehran: Virayesh; 2010.

- Kroska A. Division of domestic work. Journal of Family Issues. 2004; 25(7):900-32. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X04267149]

- Katz Wise S. Gender-role attitudes and behavior across the transition to parenthood. Developmental Psychology. 2010; 46(1):18-28. [DOI:10.1037/a0017820] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Moller K, Hwang PC. Couple relationship and transition to parenthood: Does workload at home matter? Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2008; 26(1):57-68. [DOI:10.1080/02646830701355782]

- Frisco ML, Williams K. Perceived housework equity, marital happiness and divorce in dual-earner households. Journal of Family Issues. 2003; (24):51-72. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X02238520]

- Greenstein T. National context, family satisfaction, and fairness in the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009; 71(4):1039-51. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00651.x]

- Tsuya N, Bumpass L. Employment and household tasks of Japanese couples 1994-2009. Demographic Research. 2012; 20(27):705-18. [DOI:10.4054/DemRes.2012.27.24] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Stanik CE, Bryant CM. Marital quality of newlywed African American couples: Implications of egalitarian gender role dynamics. Sex Roles. 2012; 66(3-4):256-67. [DOI:10.1007/s11199-012-0117-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

Article Type : Applicable |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2018/04/12 | Accepted: 2018/08/14 | Published: 2019/01/1

Received: 2018/04/12 | Accepted: 2018/08/14 | Published: 2019/01/1

References

1. Wagheiy Y, Miri M. [A survey about effective factors on the marital satisfaction in employees of two Birjand universities (Persian)]. Journal of Birjand University of Medical Sciences. 2010; 16(4):43-50.

2. Askarian Omran S, Sheikholeslami F, Tabari R, Kazemnejhad Leili E, Paryad E. [Role of career factors on marital satisfaction of nurses (Persian)]. Journal of Holistic Nursing and Midwifery. 2015; 25(4):102-9.

3. baneian S, parvin N, kazemian A. [Marital satisfaction of women referring to health care centers in Brojen (Persian)]. Journal of Holistic Nursing and Midwifery. 2006; 16(1):1-5.

4. Shakeriyan A. [Personality role in prediction of marital adjustment (Persian)]. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Science. 2011; 16(1):16-22.

5. Kluwer ES. From partnership to parenthood: A review of marital change across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2010; 2(2):105-25. [DOI:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00045.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00045.x]

6. Soleymanian A. [Investigating effect of unreasonable thought on marital unsatisfaction (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Tarbiat Moddares University; 2004.

7. khodakarami B, Masoumi SZ, Asadi R. [The status and marital satisfaction factors in nulliparous pregnant females attending clinics in Asadabad city during years 2015 and 2016 (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of Hamadan Nursing & Midwifery Faculty. 2017; 25(1):52-9.

8. Khezri Kh. Arjmand E. [The comparison of marital satisfaction level of working and householder women and affecting factors on them in Izeh city (Persian)]. Journal of Iranian Social Development Studies. 2014; 6(4):97-105.

9. Perry Jenkins M, Goldberg WE, Pierce CP, Sayer AG. Shift work, role overload, and the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007; 69(1):123-38. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00349.x] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00349.x]

10. Oshio T. Division of Household Labor and Marital Satisfaction in China, Japan, and Korea [MSc. thesis]. Kunitachi: Hitotsubashi University; 2006.

11. Toth K. Division of domestic labor and marital satisfaction: A cross-cultural analysis [PhD. dissertation]. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada; 2008.

12. Jacobs JA, Gerson K. The time divide: Work, family, and gender inequality (The family and public policy). Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2009.

13. Jackson J, Miller R, Oka M, Henry R. Gender differences in marital satisfaction: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014; 76(1):105-29. [DOI:10.1111/jomf.12077] [DOI:10.1111/jomf.12077]

14. Lavner JA, Karney BR, Williamson HC, Bradbury TN. Bidirectional associations between newlyweds' marital satisfaction and marital problems over time. Family Process. 2017; 56(4):869-82. [DOI:10.1111/famp.12264] [DOI:10.1111/famp.12264]

15. Newkirk K, Perry Jenkins M, Sayer A. Division of household and childcare labor and relationship conflict among low-income new parents. Journal of Sex Roles. 2017; 76(5):319-33. [DOI:10.1007/s11199-016-0604-3] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1007/s11199-016-0604-3]

16. Kubricht BC, Miller R, Yang K, Harpe J, Sandberg J. Division of household labor and marital satisfaction in China: Urban and rural comparisons. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2017; 48(2):261-74.

17. Carlson MW, Hans JD. Maximizing benefits and minimizing impacts: Dual-earner couples' perceived division of household labor decision-making process. Journal of Family Studies. 2017:1-8. [DOI:10.1080/13229400.2017.1367712] [DOI:10.1080/13229400.2017.1367712]

18. Ghobadi K, Dehghani M. [Division of household labor, perceived justice (fairness), and marital satisfaction (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2011; 7(2):207-22.

19. Nagase N, Brinton MC. The gender division of labor and second births: Labor market institutions and fertility in Japan. Demographic Research Journal. 2017; 36:339-70. [DOI:10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.11] [DOI:10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.11]

20. Maas MK, McDaniel BT, Feinberg ME, Jones DE. Division of labor and multiple domains of sexual satisfaction among first-time parents. Journal of Family Issues. 2018; 39(1):104-27. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X15604343] [DOI:10.1177/0192513X15604343]

21. Faulkner RA, Davey M, Davey A. Gender-related predictors of change in marital satisfaction and marital conflict. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2005; 33(1):61-83. [DOI:10.1080/01926180590889211] [DOI:10.1080/01926180590889211]

22. Polachek A. Gender and the division of household labor: An analysis of the implications for mental and physical health [PhD. dissertation]. Calgary: University of Calgary; 2012.

23. Lachance Grzela M. Mattering moderates the link between gender ideology and perceived fairness of the division of household labor. Interpersonal. 2012; 6(2):163-75. [DOI:10.5964/ijpr.v6i2.98] [DOI:10.5964/ijpr.v6i2.98]

24. McGovern J, Meyers S. Relationships between sex-role attitudes, division of household tasks, and marital adjustment. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2002; 24(4):601-18. [DOI:10.1023/A:1021225313735] [DOI:10.1023/A:1021225313735]

25. Fuller TD, Edwards JN, Vorakitphokatorn S, Sermsri S. Gender differences in the psychological well-being of married men and women: An Asian case. Sociological Quarterly. 2004; 45(2):355-78. [DOI:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2004.tb00016.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2004.tb00016.x]

26. Hoseni SV, Jafari N. [Lankster public health nursing: population- centered health care in the community (Persian)]. Tehran: Jameeh Negar; 2009.

27. Fowers BJ, Olson DH. ENRICH marital inventory: A discriminant validity and cross‐validation assessment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1989; 15(1):65-79. [DOI:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1989.tb00777.x] [PMID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1989.tb00777.x]

28. Saatchi M, Kamkari K, Asgarian M. [Psychological tests (Persian)]. Tehran: Virayesh; 2010.

29. Kroska A. Division of domestic work. Journal of Family Issues. 2004; 25(7):900-32. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X04267149] [DOI:10.1177/0192513X04267149]

30. Katz Wise S. Gender-role attitudes and behavior across the transition to parenthood. Developmental Psychology. 2010; 46(1):18-28. [DOI:10.1037/a0017820] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1037/a0017820]

31. Moller K, Hwang PC. Couple relationship and transition to parenthood: Does workload at home matter? Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2008; 26(1):57-68. [DOI:10.1080/02646830701355782] [DOI:10.1080/02646830701355782]

32. Frisco ML, Williams K. Perceived housework equity, marital happiness and divorce in dual-earner households. Journal of Family Issues. 2003; (24):51-72. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X02238520] [DOI:10.1177/0192513X02238520]

33. Greenstein T. National context, family satisfaction, and fairness in the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009; 71(4):1039-51. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00651.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00651.x]

34. Tsuya N, Bumpass L. Employment and household tasks of Japanese couples 1994-2009. Demographic Research. 2012; 20(27):705-18. [DOI:10.4054/DemRes.2012.27.24] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.4054/DemRes.2012.27.24]

35. Stanik CE, Bryant CM. Marital quality of newlywed African American couples: Implications of egalitarian gender role dynamics. Sex Roles. 2012; 66(3-4):256-67. [DOI:10.1007/s11199-012-0117-7] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1007/s11199-012-0117-7]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |