Fri, Apr 26, 2024

Volume 28, Issue 3 (6-2018)

JHNM 2018, 28(3): 157-162 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Bashirian S, Esmaeilpour-Zanjani S. Assessing the Health Literacy Level of Mothers of Under 5-year-old Children With Malnutrition. JHNM 2018; 28 (3) :157-162

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-614-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-614-en.html

1- Department of Nursing and Midwifery, Bojnourd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bojnourd, Iran.

2- Department of Nursing, Instructor, Islamic Azad University, Tehran Branch, Tehran, Iran. , s_esmaeilpour@yahoo.com

2- Department of Nursing, Instructor, Islamic Azad University, Tehran Branch, Tehran, Iran. , s_esmaeilpour@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 457 kb]

(1098 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4842 Views)

Full-Text: (1653 Views)

Introduction

The term “Health Literacy” refers to a set of skills that individuals need to understand the importance of getting basic health care. These skills include the ability to read, understand and interpret information of some parameters such as food labels, measuring blood glucose levels and compliance with prescription diets [1]. This term was first introduced in 1970, and its importance in the field of public health and health care is increasing day by day [2]. In the United States, low health literacy is one of the main problems in the field of health [3]. In a health literacy study in Kerman City, Iran, it was found that 4.8% people had inadequate health literacy and only 53.8% had adequate literacy levels [4]. Results of a study showed that the parents with low health literacy have lesser ability to interpret information on the food labels [5]. Hence, mothers with lower levels of health literacy seem to lack a clear understanding on the issues of nutrition and malnutrition in their children and thus, unable to meet the nutritional needs of their child [6]. The proper nutrition of the child is essential for their normal growth, resistance to infections, prolonged health in adulthood, neurological and cognitive development [7].

Developing countries have the highest percentage of undernourished children and nearly 60% of deaths of children under the age of 5 in such countries are directly related to malnutrition and subsequent diseases [8]. According to reports, malnutrition is the leading cause of child mortality in the world and accounts for half of their deaths [9]. In Iran, malnutrition of children is one of the nutritional health problems [10]. About 7.4% of children in the whole country have short stature (stunting) 2.5% are underweight at birth and the prevalence of weight loss (wasting) in children under the age of 5 years is 7.3% [11]. Malnutrition rate in Bojnourd City has been reported as 3%, 4.8% and 4.9% based on weight-for-height, height-for-age and head circumference-for-age, respectively [12]. In mothers with a lower level of health literacy, the probability of having a baby with low birth weight is also higher. Moreover, these women are more likely to delay seeking prenatal care. Mothers with a higher level of health literacy were less likely to have anemia due to the higher use of supplements and vitamins during pregnancy. All indicate that in lower-educated mothers, the baby born is of lower health status [13]. Ashraf-Ganjoei et al. [14] in their study showed that women with lower literacy receive less care during pregnancy and they begin their parental care at a higher gestational age. According to Yee and Simon [15], women with lower levels of health literacy are more likely to experience adverse pregnancy complications. The findings from another study suggested that pregnant and lactating women should attend training classes to increase their health literacy and become familiar with the warning signs of pregnancy [16].

Despite the great importance of health literacy for mother and child health as well as the significant rate of malnutrition in Iran and Bojnord, this issue has not been addressed too much. One example for the effects of health literacy can be on the process of raising children by mothers and more generally by the family. The aim of this study was to determine the level of health literacy in mothers of children under the age of 5 years suffering from malnutrition among families supported by health centers in Bojnord City.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional and analytical study conducted on mothers of the children under 5 years of age, supported by the health centers in Bojnord City in 2015.

The sampling process was as following: after explaining the objectives of the study and obtaining written consent from the participants, they were selected based on the inclusion criteria. Then the questionnaire was presented to the subjects, and the research method was explained to them. Also, they were assured of the confidentiality of their personal information. Collected data was analyzed in SPSS 22 using descriptive statistics. Since the distribution of health literacy data was not normal according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to examine the differences between the study groups.

The inclusion criteria were children with malnutrition supported by Bojnord health centers, and the exclusion criteria were mothers who were not able to respond correctly, defective child health records, children with acute and chronic diseases and dehydrated children. To take the maximum sample size, the P value was considered as 50%. To determine the sample size, according to the formula, considering 95% confidence level (α=0.05, z1.96) and maximum acceptable error (d=0.05), the sample size required for this study was obtained as 400. Finally, 448 mothers having malnourished children were evaluated. In this study, cluster sampling method was used in two stages: first Bojnord City was divided into two districts based on local divisions, and each district had five health centers. The area under the supervision of each health center was considered as a cluster. Finally, from each health center (cluster), an average of 45 samples was included in the study depending upon the inclusion criteria.

To assess malnutrition, the height of the children under 2 years of age was measured in lying position; the height of children over 2 years was measured in standing position; the weight was measured with a calibrated scale by the researcher and to be assured these indices were measured twice, and the mean was recorded as the final result. The nutritional status of the children was examined based on the three indicators of weight-for-age, weight-for-height and height-for-age (based on the standard child growth tables) which are used to determine underweight, wasting and stunting statuses [11].

After selecting 448 mothers with malnourished children, the information was collected by two questionnaires from them. The first questionnaire was an inventory related to the demographic characteristics of the child and the mother, and the second was the test for functional health literacy in adults. This tool consists of two sections: a. Reading comprehension; and b. Numerical ability. In the reading section, the subject’s ability for reading authentic texts related to health care was evaluated. This section included three texts related to the instructions for upper gastrointestinal imaging, the patient’s rights and responsibilities in the insurance forms and a consent form. They are provided in 50 questions each with 4 answers. In the numeracy section with 17 items, patients are presented with cue cards containing explanations of some medications, clinic appointments, obtaining financial assistance and an example of a blood glucose test result.

The patients were given 20 minutes to answer reading comprehension questions and 10 minutes for answering numeracy section. After 30 minutes, the questionnaires were collected, even though incomplete. Each of the 50 questions in the reading comprehension section has 1 point score (total score=50), and the score of 17 questions in the numeracy section was factorized by 2.941 to reach 50 (at most), and the total score of the questionnaire was calculated in a range from 0 to 100. The health literacy scores of the patients were then classified into three categories of inadequate (0-59), marginal (60-74) and adequate (above 75) levels [17].

Face and content validity of this tool was confirmed by the faculty professors. Its reliability, through a 10-day retest on 10% of the subjects (N=45) who completed the health literacy questionnaire, was measured using the Spearman test and the results showed appropriate reliability (r=0.91). After receiving the approval letter (code No. 5.1821) from the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University of Tehran Medical Branch, and receiving an introduction letter from the faculty and relevant authorities, the researcher approached to the health centers of Bojnord City and received permission from them.

Results

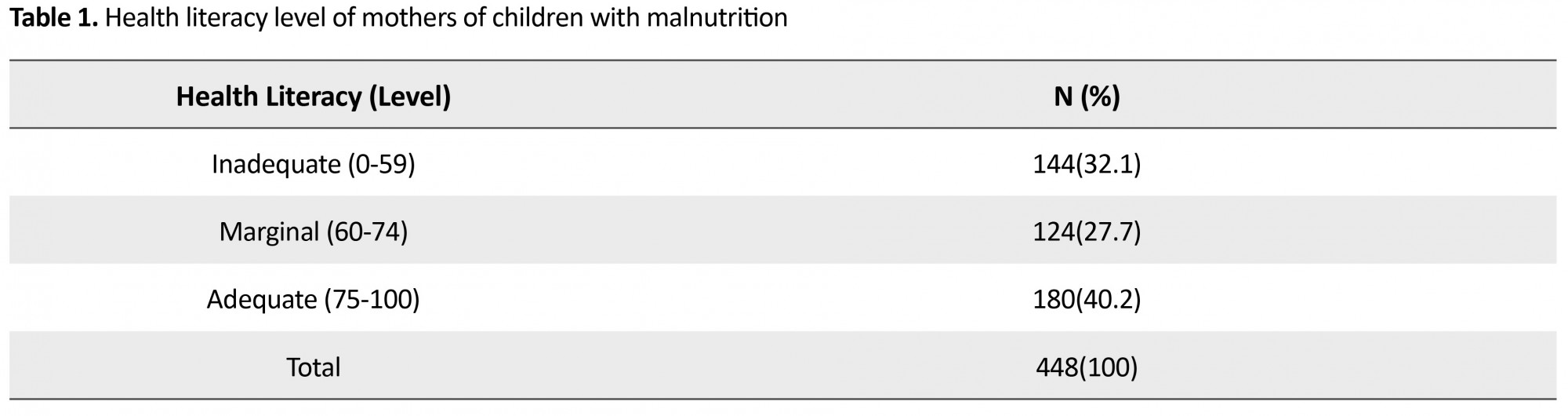

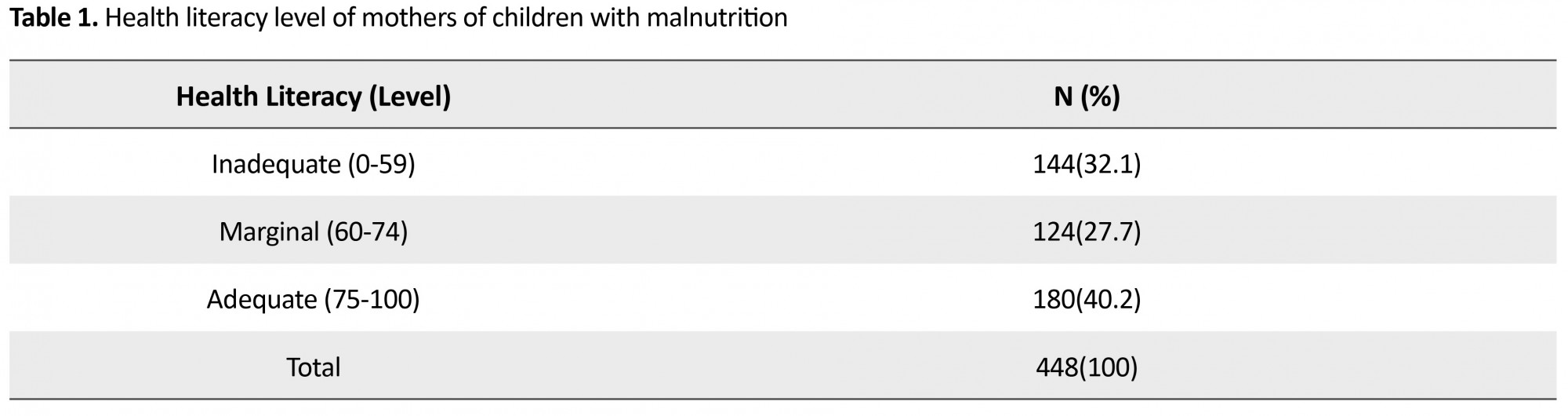

According to the study results, most of the children (58.9%) were girls. About 39.7% of children were second-born child, and most of them (83.9%) had malnutrition in the form of underweight; 45.5% were between 1-10 months old, and 65% had a birth weight of 2.8-3.8 kg. According to the Table 1, most mothers (40.2%) had adequate health literacy (75-100); 27.7% were at marginal level (60-74), and 32.1% had inadequate health literacy level (0-59). Most of the mothers had a university degree (39.7%) and were housewives (72.8%) while many (71.2%) were between the age of 26 and 40 years.

The term “Health Literacy” refers to a set of skills that individuals need to understand the importance of getting basic health care. These skills include the ability to read, understand and interpret information of some parameters such as food labels, measuring blood glucose levels and compliance with prescription diets [1]. This term was first introduced in 1970, and its importance in the field of public health and health care is increasing day by day [2]. In the United States, low health literacy is one of the main problems in the field of health [3]. In a health literacy study in Kerman City, Iran, it was found that 4.8% people had inadequate health literacy and only 53.8% had adequate literacy levels [4]. Results of a study showed that the parents with low health literacy have lesser ability to interpret information on the food labels [5]. Hence, mothers with lower levels of health literacy seem to lack a clear understanding on the issues of nutrition and malnutrition in their children and thus, unable to meet the nutritional needs of their child [6]. The proper nutrition of the child is essential for their normal growth, resistance to infections, prolonged health in adulthood, neurological and cognitive development [7].

Developing countries have the highest percentage of undernourished children and nearly 60% of deaths of children under the age of 5 in such countries are directly related to malnutrition and subsequent diseases [8]. According to reports, malnutrition is the leading cause of child mortality in the world and accounts for half of their deaths [9]. In Iran, malnutrition of children is one of the nutritional health problems [10]. About 7.4% of children in the whole country have short stature (stunting) 2.5% are underweight at birth and the prevalence of weight loss (wasting) in children under the age of 5 years is 7.3% [11]. Malnutrition rate in Bojnourd City has been reported as 3%, 4.8% and 4.9% based on weight-for-height, height-for-age and head circumference-for-age, respectively [12]. In mothers with a lower level of health literacy, the probability of having a baby with low birth weight is also higher. Moreover, these women are more likely to delay seeking prenatal care. Mothers with a higher level of health literacy were less likely to have anemia due to the higher use of supplements and vitamins during pregnancy. All indicate that in lower-educated mothers, the baby born is of lower health status [13]. Ashraf-Ganjoei et al. [14] in their study showed that women with lower literacy receive less care during pregnancy and they begin their parental care at a higher gestational age. According to Yee and Simon [15], women with lower levels of health literacy are more likely to experience adverse pregnancy complications. The findings from another study suggested that pregnant and lactating women should attend training classes to increase their health literacy and become familiar with the warning signs of pregnancy [16].

Despite the great importance of health literacy for mother and child health as well as the significant rate of malnutrition in Iran and Bojnord, this issue has not been addressed too much. One example for the effects of health literacy can be on the process of raising children by mothers and more generally by the family. The aim of this study was to determine the level of health literacy in mothers of children under the age of 5 years suffering from malnutrition among families supported by health centers in Bojnord City.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional and analytical study conducted on mothers of the children under 5 years of age, supported by the health centers in Bojnord City in 2015.

The sampling process was as following: after explaining the objectives of the study and obtaining written consent from the participants, they were selected based on the inclusion criteria. Then the questionnaire was presented to the subjects, and the research method was explained to them. Also, they were assured of the confidentiality of their personal information. Collected data was analyzed in SPSS 22 using descriptive statistics. Since the distribution of health literacy data was not normal according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to examine the differences between the study groups.

The inclusion criteria were children with malnutrition supported by Bojnord health centers, and the exclusion criteria were mothers who were not able to respond correctly, defective child health records, children with acute and chronic diseases and dehydrated children. To take the maximum sample size, the P value was considered as 50%. To determine the sample size, according to the formula, considering 95% confidence level (α=0.05, z1.96) and maximum acceptable error (d=0.05), the sample size required for this study was obtained as 400. Finally, 448 mothers having malnourished children were evaluated. In this study, cluster sampling method was used in two stages: first Bojnord City was divided into two districts based on local divisions, and each district had five health centers. The area under the supervision of each health center was considered as a cluster. Finally, from each health center (cluster), an average of 45 samples was included in the study depending upon the inclusion criteria.

To assess malnutrition, the height of the children under 2 years of age was measured in lying position; the height of children over 2 years was measured in standing position; the weight was measured with a calibrated scale by the researcher and to be assured these indices were measured twice, and the mean was recorded as the final result. The nutritional status of the children was examined based on the three indicators of weight-for-age, weight-for-height and height-for-age (based on the standard child growth tables) which are used to determine underweight, wasting and stunting statuses [11].

After selecting 448 mothers with malnourished children, the information was collected by two questionnaires from them. The first questionnaire was an inventory related to the demographic characteristics of the child and the mother, and the second was the test for functional health literacy in adults. This tool consists of two sections: a. Reading comprehension; and b. Numerical ability. In the reading section, the subject’s ability for reading authentic texts related to health care was evaluated. This section included three texts related to the instructions for upper gastrointestinal imaging, the patient’s rights and responsibilities in the insurance forms and a consent form. They are provided in 50 questions each with 4 answers. In the numeracy section with 17 items, patients are presented with cue cards containing explanations of some medications, clinic appointments, obtaining financial assistance and an example of a blood glucose test result.

The patients were given 20 minutes to answer reading comprehension questions and 10 minutes for answering numeracy section. After 30 minutes, the questionnaires were collected, even though incomplete. Each of the 50 questions in the reading comprehension section has 1 point score (total score=50), and the score of 17 questions in the numeracy section was factorized by 2.941 to reach 50 (at most), and the total score of the questionnaire was calculated in a range from 0 to 100. The health literacy scores of the patients were then classified into three categories of inadequate (0-59), marginal (60-74) and adequate (above 75) levels [17].

Face and content validity of this tool was confirmed by the faculty professors. Its reliability, through a 10-day retest on 10% of the subjects (N=45) who completed the health literacy questionnaire, was measured using the Spearman test and the results showed appropriate reliability (r=0.91). After receiving the approval letter (code No. 5.1821) from the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University of Tehran Medical Branch, and receiving an introduction letter from the faculty and relevant authorities, the researcher approached to the health centers of Bojnord City and received permission from them.

Results

According to the study results, most of the children (58.9%) were girls. About 39.7% of children were second-born child, and most of them (83.9%) had malnutrition in the form of underweight; 45.5% were between 1-10 months old, and 65% had a birth weight of 2.8-3.8 kg. According to the Table 1, most mothers (40.2%) had adequate health literacy (75-100); 27.7% were at marginal level (60-74), and 32.1% had inadequate health literacy level (0-59). Most of the mothers had a university degree (39.7%) and were housewives (72.8%) while many (71.2%) were between the age of 26 and 40 years.

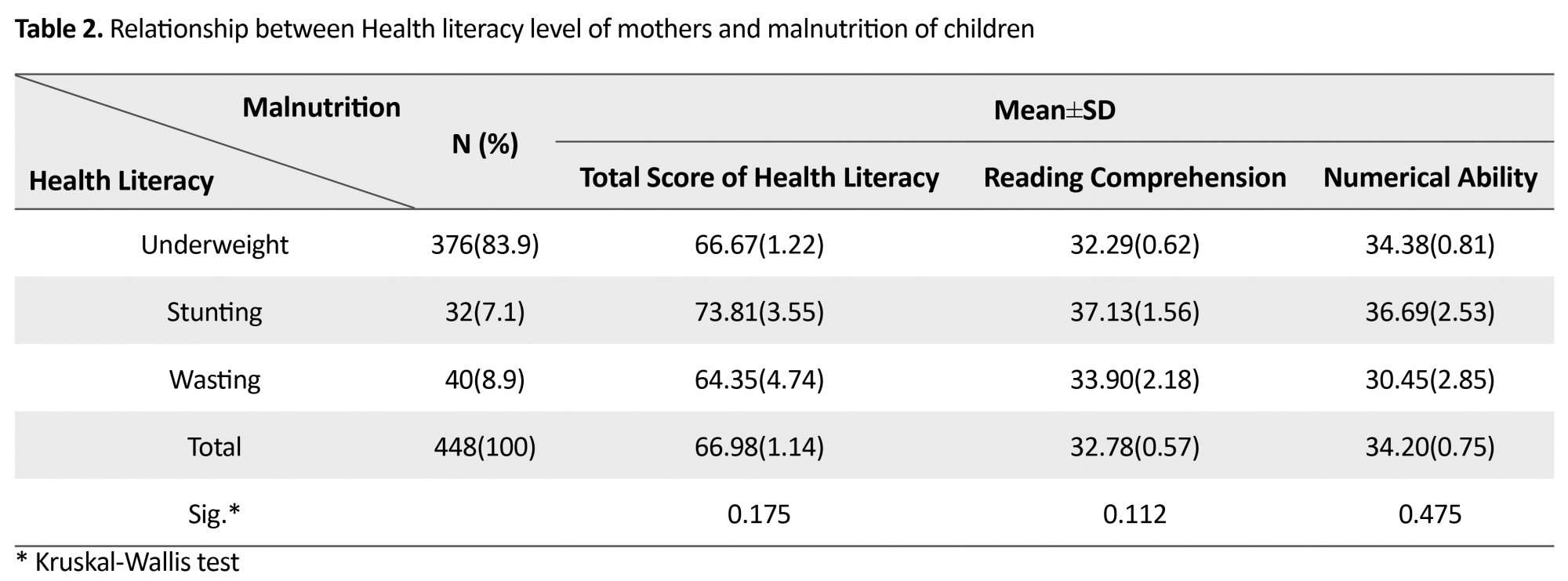

The means for the scores of overall health literacy, reading comprehension, and numerical ability were reported as 66.98±1.14, 32.78±0.57, and 34.20±0.75, respectively (Table 2). Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess the difference in these scores among different malnutrition groups. The scores for these three factors in the three groups of stunted, wasted and underweight children was not statistically significant.

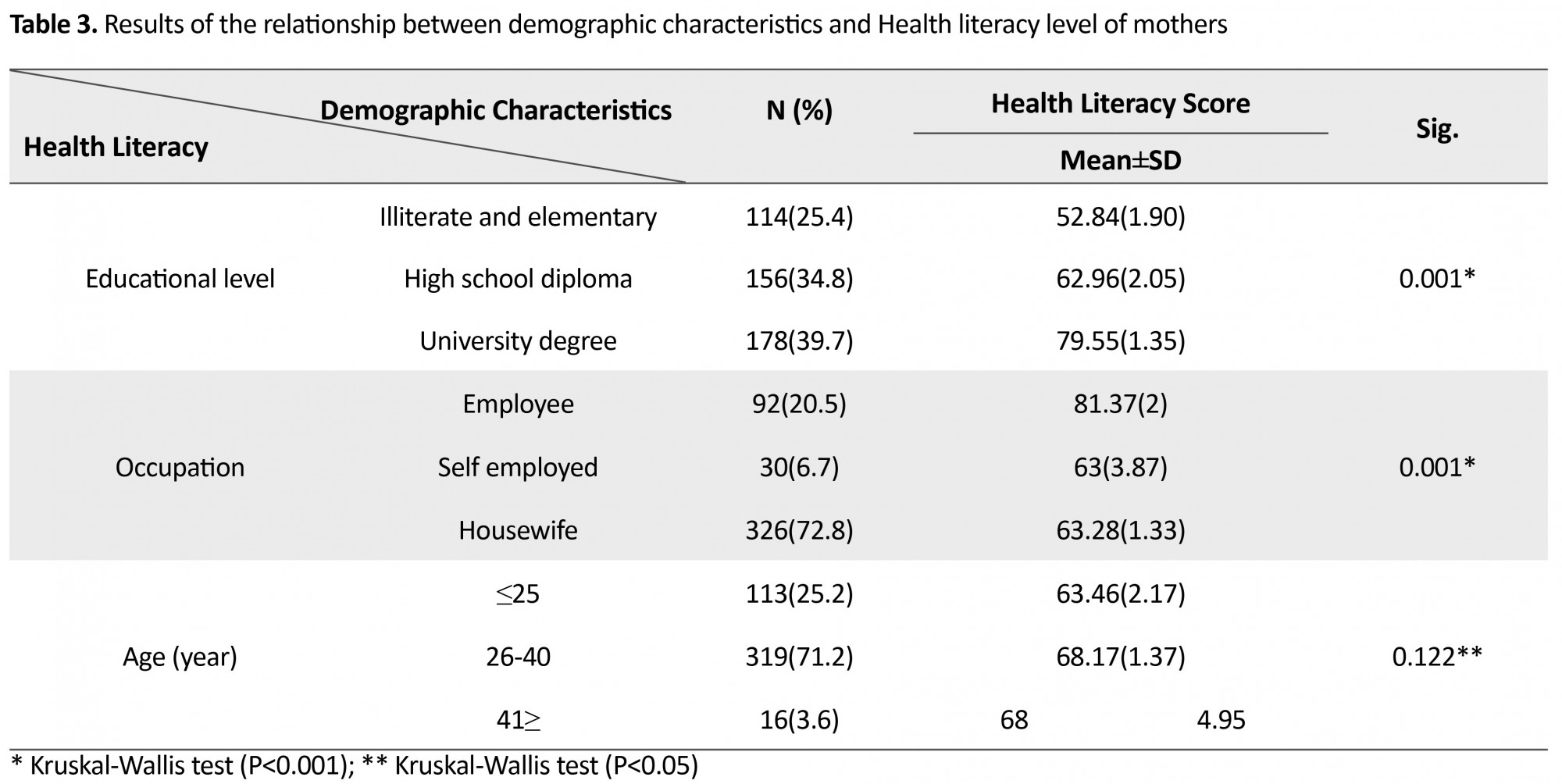

Based on the results presented in Table 3, there was a significant relationship between education and health literacy level where higher educational levels increased the health literacy levels in the mothers (P=0.001). Also, between the job and the health literacy level, there was a significant association; mothers with in-office jobs (employee) had higher levels of health literacy as compared to those with other jobs (P=0.001). About age and its effect on the level of health literacy, no significant relationship was found between mothers of different age groups.

Discussion

The results of the current study showed that most of the mothers of malnourished children had a high level of health literacy, and there was no significant relationship between malnutrition and health literacy level. The relationship between mothers’ demographic characteristics and health literacy level of participants showed that, in terms of education, housewife mothers compared to other occupations, had a higher level of health literacy. With regard to age and its effect on health literacy, no significant relationship was not found between different age groups of mothers.

In Ghaljaei et al. study [18], the most prevalent malnutrition outcomes were underweight, stunting, and wasting. Also, malnutrition in children had a statistically significant association with birth weight, mother’s job and the duration of breastfeeding [18]. Similar to these findings, in the present study, the most prevalent malnourishment symptoms among children were lower weight followed by stunting and wasting. Results of Yin et al. [19] in America showed that health literacy of almost one-third of the people was below the standard level. In the present study, most mothers were at a high level of health literacy; however, a significant proportion of the population had an inadequate level of health literacy. Studies have shown that overall, health literacy in Iran is low and most parents of malnourished children with inadequate health literacy are in need of interventional and educational programs [20].

Carthery-Goulart et al. [21] showed that health literacy was positively correlated with schooling and negatively correlated with age. Education was a significant predictor of health literacy and illiterate people needed special assistance to properly understand the health care directions. La Vonne et al. [22] also pointed out that the health literacy level had a relationship with the education and age. Artinian et al. [23] reported that patients with inadequate health literacy were significantly older, had lower functional literacy and annual income. Adequate health literacy had a significant association with age, race, education, marital status, income, employment status and car ownership which were possible predictors for health literacy. In another study, Reisi et al. [24] found out that adults with inadequate health literacy level tend to be older, had lesser years of schooling, lower household income and were females. Similarly, in the present study there was a significant relationship between mother’s job and health literacy level. Employee mothers had higher level of health literacy than others. Also, there was a significant association between their educational level and health literacy level; with the increase in the educational level, their health literacy level increased.

Other differences such as the individual, social, cultural and economic differences of the subjects also had effect on their responsiveness and consequently the level of health literacy, but they were not examined in this study due to their high complexity. In a similar study, on 319 mothers in Karachi, Pakistan, maximum loss of weight was seen in children whose mothers had low educational level [25]. A review study in 2014, argued that the increase in health literacy level of parents can also improve the health of children [26]. On the other hand, mothers with a higher educational level perform better in vaccination and nutrition of children than the mothers with lower educational level [27]. These studies show that health literacy in parents, especially in mothers, have a direct impact on the health of children and should be improved by various methods.

Regarding the results of this study, mothers’ health literacy played an important role in the nutrition of children and given the fact that the health literacy can be affected by educational level, the mothers can be taught to increase their health literacy. Although the results of the present study showed that mothers in high number had an adequate level of health literacy; however, a significant proportion of them also had marginal or inadequate health literacy level. In this regard, by devising educational programs and materials that are understandable to the public, the level of health literacy in the community can be promoted, and thus the negative effects of low level of the health literacy in the society can be reduced.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The process of the research was explained to all the participants. All the participants signed the consent form.

Funding

This study was extracted from an MS thesis in the field of Child Nursing which was submitted to Islamic Azad University of Tehran Medical Branch.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank health authorities in Bojnord City and those who helped us in conducting this research.

References

The results of the current study showed that most of the mothers of malnourished children had a high level of health literacy, and there was no significant relationship between malnutrition and health literacy level. The relationship between mothers’ demographic characteristics and health literacy level of participants showed that, in terms of education, housewife mothers compared to other occupations, had a higher level of health literacy. With regard to age and its effect on health literacy, no significant relationship was not found between different age groups of mothers.

In Ghaljaei et al. study [18], the most prevalent malnutrition outcomes were underweight, stunting, and wasting. Also, malnutrition in children had a statistically significant association with birth weight, mother’s job and the duration of breastfeeding [18]. Similar to these findings, in the present study, the most prevalent malnourishment symptoms among children were lower weight followed by stunting and wasting. Results of Yin et al. [19] in America showed that health literacy of almost one-third of the people was below the standard level. In the present study, most mothers were at a high level of health literacy; however, a significant proportion of the population had an inadequate level of health literacy. Studies have shown that overall, health literacy in Iran is low and most parents of malnourished children with inadequate health literacy are in need of interventional and educational programs [20].

Carthery-Goulart et al. [21] showed that health literacy was positively correlated with schooling and negatively correlated with age. Education was a significant predictor of health literacy and illiterate people needed special assistance to properly understand the health care directions. La Vonne et al. [22] also pointed out that the health literacy level had a relationship with the education and age. Artinian et al. [23] reported that patients with inadequate health literacy were significantly older, had lower functional literacy and annual income. Adequate health literacy had a significant association with age, race, education, marital status, income, employment status and car ownership which were possible predictors for health literacy. In another study, Reisi et al. [24] found out that adults with inadequate health literacy level tend to be older, had lesser years of schooling, lower household income and were females. Similarly, in the present study there was a significant relationship between mother’s job and health literacy level. Employee mothers had higher level of health literacy than others. Also, there was a significant association between their educational level and health literacy level; with the increase in the educational level, their health literacy level increased.

Other differences such as the individual, social, cultural and economic differences of the subjects also had effect on their responsiveness and consequently the level of health literacy, but they were not examined in this study due to their high complexity. In a similar study, on 319 mothers in Karachi, Pakistan, maximum loss of weight was seen in children whose mothers had low educational level [25]. A review study in 2014, argued that the increase in health literacy level of parents can also improve the health of children [26]. On the other hand, mothers with a higher educational level perform better in vaccination and nutrition of children than the mothers with lower educational level [27]. These studies show that health literacy in parents, especially in mothers, have a direct impact on the health of children and should be improved by various methods.

Regarding the results of this study, mothers’ health literacy played an important role in the nutrition of children and given the fact that the health literacy can be affected by educational level, the mothers can be taught to increase their health literacy. Although the results of the present study showed that mothers in high number had an adequate level of health literacy; however, a significant proportion of them also had marginal or inadequate health literacy level. In this regard, by devising educational programs and materials that are understandable to the public, the level of health literacy in the community can be promoted, and thus the negative effects of low level of the health literacy in the society can be reduced.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The process of the research was explained to all the participants. All the participants signed the consent form.

Funding

This study was extracted from an MS thesis in the field of Child Nursing which was submitted to Islamic Azad University of Tehran Medical Branch.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank health authorities in Bojnord City and those who helped us in conducting this research.

References

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011; 155(2):97-107. [DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005] [PMID]

- Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, et al. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12(1):80. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-12-80] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sheridan SL, Halpern DJ, Viera AJ, Berkman ND, Donahue KE, Crotty K. Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: A systematic review. Journal of Health Communication. 2011; 16(sup3):30-54. [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2011.604391]

- Nekoei-Moghadam M, Parva S, Amiresmaili M, Baneshi M. [Health Literacy and Utilization of health Services in Kerman urban Area 2011 (Persian)]. Toloo-e-Behdasht. 2012; 11(14):123-34.

- Sanders LM, Shaw JS, Guez G, Baur C, Rudd R. Health literacy and child health promotion: Implications for research, clinical care, and public policy. Paediatrics. 2009; 124(Supplement 3):S306-S14. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2009-1162G] [PMID]

- Asgary R, Liu M, Naderi R, Grigoryan Z, Malachovsky M. Malnutrition prevalence and nutrition barriers in children under 5 years: A mixed methods study in Madagascar. International Health. 2015; 7(6):426-32. [DOI:10.1093/inthealth/ihv016] [PMID]

- Marcdante K, Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB. Nelson essentials of pediatrics. New York: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2010.

- Cervantes-Ríos E, Ortiz-Mu-iz R, Martínez-Hernández AL, Cabrera-Rojo L, Graniel-Guerrero J, Rodríguez-Cruz L. Malnutrition and infection influence the peripheral blood reticulocyte micronuclei frequency in children. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2012; 731(1):68-74. [DOI:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.11.006] [PMID]

- Brady JP. Marketing breast milk substitutes: Problems and perils throughout the world. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2012; 97(6):529-32. [DOI:10.1136/archdischild-2011-301299] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Esfahani M, Dorosty-Motlagh AR, Sadrzadeh Yeganeh H, Rahimi Frushani A. [The association of feeding practices in the second six months of life with later under nutrition at 1-year old children: Findings from the Household Food Security Study (HFSS) (Persian)]. 2014; 13(3):301-11.

- Sheikholeslam R, Naghavi M, Abdollahi Z, Zarati M, Vaseghi S, Sadeghi Ghotbabadi F, et al. [Current Status and the 10 Years Trend in the Malnutrition Indexes of Children under 5 years in Iran (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Epidemiology. 2008; 4(1):21-8.

- Khosravi M, Keshavarz SA, Hoseini M. [Newborn nutrintional status using anthropometry method and some effectral factors In Bojnord – 2001 (Persian)]. Tehran University Medical Journal. 2005; 63(1):40-2.

- Kharazi SS, Peyman N, Esmaily H. [Association between maternal health literacy level with pregnancy care and its outcomes (Persian)]. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2016; 19(37):40-50.

- Ashraf-Ganjoei T, Mirzaei F, Anari-Dokht F. Relationship between prenatal care and the outcome of pregnancy in low-risk pregnancies. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2011; 1(03):109. [DOI:10.4236/ojog.2011.13019]

- Yee LM, Simon MA. The role of health literacy and numeracy in contraceptive decision-making for urban Chicago women. Journal of Community Health. 2014; 39(2):394-9. [DOI:10.1007/s10900-013-9777-7] [PMID]

- Mojoyinola J. Influence of maternal health literacy on healthy pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes of women attending public hospitals in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. African Research Review. 2011; 5(3):28-39. [DOI:10.4314/afrrev.v5i3.67336]

- Parikh NS, Parker RM, Nurss JR, Baker DW, Williams MV. Shame and health literacy: The unspoken connection. Patient Education and Counseling. 1996; 27(1):33-9. [DOI:10.1016/0738-3991(95)00787-3]

- Ghaljaei F, Nadrifar M, Ghaljeh M. [Prevalence of malnutrition among 1-36 month old children hospitalized at Imam Ali Hospital in Zahedan (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Nursing. 2009; 22(59):8-14.

- Yin HS, Johnson M, Mendelsohn AL, Abrams MA, Sanders LM, Dreyer BP. The health literacy of parents in the United States: A nationally representative study. Pediatrics. 2009; 124(Supplement 3):S289-S98. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2009-1162E] [PMID]

- Tehrani Banihashemi SA, Amirkhani MA, Haghdoost AA, Alavian S-M, Asgharifard H, Baradaran H, et al. [Health Literacy and the Influencing Factors: A Study in Five Provinces of Iran (Persian)]. Strides in Development of Medical Education. 2007; 4(1):1-9.

- Carthery-Goulart MT, Anghinah R, Areza-Fegyveres R, Bahia VS, Brucki SMD, Damin A, et al. Performance of a Brazilian population on the test of functional health literacy in adults. Revista de Saúde Pública. 2009; 43(4):631-8. [DOI:10.1590/S0034-89102009005000031] [PMID]

- La Vonne A, Zun LS. Assessing adult health literacy in urban healthcare settings. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2008; 100(11):1304. [DOI:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31509-1]

- Artinian NT, Lange MP, Templin T, Stallwood LG, Hermann CE. Functional health literacy in an urban primary care clinic. The Internet Journal of Advanced Nursing Practice .2003; 5(2). [DOI: 10.5580/deb]

- Reisi M, Mostafavi F, Hasanzadeh A, Sharifirad Gr. [The relationship between health literacy, health status and healthy behaviors among elderly in Isfahan, Iran (Persian)]. 2011; 7(4):469-80.

- Ali SS, Karim N, Billoo AG, Haider SS. Association of literacy of mothers with malnutrition among children under three years of age in rural area of district Malir, Karachi. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 2005; 55(12):550-3. [PMID: 16438277]

- Aslam M, Kingdon GG. Parental education and child health—understanding the pathways of impact in Pakistan. World Development. 2012; 40(10):2014-32. [DOI:10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.007]

- Ali S, Tahir C, Qurat-ul-ain N. Effect of maternal literacy on child health: Myth or reality. Annals of Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences. 2011; 7:100-3.

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2016/02/9 | Accepted: 2016/05/18 | Published: 2018/06/15

Received: 2016/02/9 | Accepted: 2016/05/18 | Published: 2018/06/15

References

1. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011; 155(2):97-107. [DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005] [PMID] [DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005]

2. Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, et al. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12(1):80. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-12-80] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-12-80]

3. Sheridan SL, Halpern DJ, Viera AJ, Berkman ND, Donahue KE, Crotty K. Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: A systematic review. Journal of Health Communication. 2011; 16(sup3):30-54. [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2011.604391] [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2011.604391]

4. Nekoei-Moghadam M, Parva S, Amiresmaili M, Baneshi M. [Health Literacy and Utilization of health Services in Kerman urban Area 2011 (Persian)]. Toloo-e-Behdasht. 2012; 11(14):123-34.

5. Sanders LM, Shaw JS, Guez G, Baur C, Rudd R. Health literacy and child health promotion: Implications for research, clinical care, and public policy. Paediatrics. 2009; 124(Supplement 3):S306-S14. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2009-1162G] [PMID] [DOI:10.1542/peds.2009-1162G]

6. Asgary R, Liu M, Naderi R, Grigoryan Z, Malachovsky M. Malnutrition prevalence and nutrition barriers in children under 5 years: A mixed methods study in Madagascar. International Health. 2015; 7(6):426-32. [DOI:10.1093/inthealth/ihv016] [PMID] [DOI:10.1093/inthealth/ihv016]

7. Marcdante K, Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB. Nelson essentials of pediatrics. New York: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2010.

8. Cervantes-Ríos E, Ortiz-Mu-iz R, Martínez-Hernández AL, Cabrera-Rojo L, Graniel-Guerrero J, Rodríguez-Cruz L. Malnutrition and infection influence the peripheral blood reticulocyte micronuclei frequency in children. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2012; 731(1):68-74. [DOI:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.11.006] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.11.006]

9. Brady JP. Marketing breast milk substitutes: Problems and perils throughout the world. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2012; 97(6):529-32. [DOI:10.1136/archdischild-2011-301299] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1136/archdischild-2011-301299]

10. Esfahani M, Dorosty-Motlagh AR, Sadrzadeh Yeganeh H, Rahimi Frushani A. [The association of feeding practices in the second six months of life with later under nutrition at 1-year old children: Findings from the Household Food Security Study (HFSS) (Persian)]. 2014; 13(3):301-11.

11. Sheikholeslam R, Naghavi M, Abdollahi Z, Zarati M, Vaseghi S, Sadeghi Ghotbabadi F, et al. [Current Status and the 10 Years Trend in the Malnutrition Indexes of Children under 5 years in Iran (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Epidemiology. 2008; 4(1):21-8.

12. Khosravi M, Keshavarz SA, Hoseini M. [Newborn nutrintional status using anthropometry method and some effectral factors In Bojnord – 2001 (Persian)]. Tehran University Medical Journal. 2005; 63(1):40-2.

13. Kharazi SS, Peyman N, Esmaily H. [Association between maternal health literacy level with pregnancy care and its outcomes (Persian)]. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2016; 19(37):40-50.

14. Ashraf-Ganjoei T, Mirzaei F, Anari-Dokht F. Relationship between prenatal care and the outcome of pregnancy in low-risk pregnancies. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2011; 1(03):109. [DOI:10.4236/ojog.2011.13019] [DOI:10.4236/ojog.2011.13019]

15. Yee LM, Simon MA. The role of health literacy and numeracy in contraceptive decision-making for urban Chicago women. Journal of Community Health. 2014; 39(2):394-9. [DOI:10.1007/s10900-013-9777-7] [PMID] [DOI:10.1007/s10900-013-9777-7]

16. Mojoyinola J. Influence of maternal health literacy on healthy pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes of women attending public hospitals in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. African Research Review. 2011; 5(3):28-39. [DOI:10.4314/afrrev.v5i3.67336] [DOI:10.4314/afrrev.v5i3.67336]

17. Parikh NS, Parker RM, Nurss JR, Baker DW, Williams MV. Shame and health literacy: The unspoken connection. Patient Education and Counseling. 1996; 27(1):33-9. [DOI:10.1016/0738-3991(95)00787-3] [DOI:10.1016/0738-3991(95)00787-3]

18. Ghaljaei F, Nadrifar M, Ghaljeh M. [Prevalence of malnutrition among 1-36 month old children hospitalized at Imam Ali Hospital in Zahedan (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Nursing. 2009; 22(59):8-14.

19. Yin HS, Johnson M, Mendelsohn AL, Abrams MA, Sanders LM, Dreyer BP. The health literacy of parents in the United States: A nationally representative study. Pediatrics. 2009; 124(Supplement 3):S289-S98. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2009-1162E] [PMID] [DOI:10.1542/peds.2009-1162E]

20. Tehrani Banihashemi SA, Amirkhani MA, Haghdoost AA, Alavian S-M, Asgharifard H, Baradaran H, et al. [Health Literacy and the Influencing Factors: A Study in Five Provinces of Iran (Persian)]. Strides in Development of Medical Education. 2007; 4(1):1-9.

21. Carthery-Goulart MT, Anghinah R, Areza-Fegyveres R, Bahia VS, Brucki SMD, Damin A, et al. Performance of a Brazilian population on the test of functional health literacy in adults. Revista de Saúde Pública. 2009; 43(4):631-8. [DOI:10.1590/S0034-89102009005000031] [PMID] [DOI:10.1590/S0034-89102009005000031]

22. La Vonne A, Zun LS. Assessing adult health literacy in urban healthcare settings. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2008; 100(11):1304. [DOI:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31509-1] [DOI:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31509-1]

23. Artinian NT, Lange MP, Templin T, Stallwood LG, Hermann CE. Functional health literacy in an urban primary care clinic. The Internet Journal of Advanced Nursing Practice .2003; 5(2). [DOI: 10.5580/deb] [DOI:10.5580/deb]

24. Reisi M, Mostafavi F, Hasanzadeh A, Sharifirad Gr. [The relationship between health literacy, health status and healthy behaviors among elderly in Isfahan, Iran (Persian)]. 2011; 7(4):469-80.

25. Ali SS, Karim N, Billoo AG, Haider SS. Association of literacy of mothers with malnutrition among children under three years of age in rural area of district Malir, Karachi. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 2005; 55(12):550-3. [PMID: 16438277] [PMID]

26. Aslam M, Kingdon GG. Parental education and child health—understanding the pathways of impact in Pakistan. World Development. 2012; 40(10):2014-32. [DOI:10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.007] [DOI:10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.007]

27. Ali S, Tahir C, Qurat-ul-ain N. Effect of maternal literacy on child health: Myth or reality. Annals of Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences. 2011; 7:100-3.

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |