Mon, May 6, 2024

Volume 28, Issue 3 (6-2018)

JHNM 2018, 28(3): 171-178 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Heidarzadeh M, Chookalayi H, Jabrailzadeh S, Hashemi M, Kiani M, Kohi F. Determination of Psychometric Properties of Non-Verbal Pain Scale in Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilation. JHNM 2018; 28 (3) :171-178

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-563-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-563-en.html

Mehdi Heidarzadeh1

, Hoda Chookalayi *

, Hoda Chookalayi *

2, Sajjad Jabrailzadeh3

2, Sajjad Jabrailzadeh3

, Morteza Hashemi3

, Morteza Hashemi3

, Mehrdad Kiani3

, Mehrdad Kiani3

, Farzad Kohi3

, Farzad Kohi3

, Hoda Chookalayi *

, Hoda Chookalayi *

2, Sajjad Jabrailzadeh3

2, Sajjad Jabrailzadeh3

, Morteza Hashemi3

, Morteza Hashemi3

, Mehrdad Kiani3

, Mehrdad Kiani3

, Farzad Kohi3

, Farzad Kohi3

1- Department of Nursing, Assistant Professor, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran.

2- Nursing (MSN), School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran. , yaminfaresw@yahoo.co

3- Nursing (BSN), School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran.

2- Nursing (MSN), School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran. , yaminfaresw@yahoo.co

3- Nursing (BSN), School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 468 kb]

(1029 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3483 Views)

Full-Text: (1730 Views)

Introduction

Patients admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICUs) frequently experience pain and discomfort during their stay [1]. Pain continues to be a major stressor in ICUs [2], where it is difficult to assess pain given the presence of illness and life-threatening injuries [3]. Pain assessment is not only the first step in the proper relief of pain but also one of the most important goals in patient care [4]. Since pain is a subjective phenomenon, the most reliable tool for pain assessment is the patient’s own report [5], but most patients in the ICU are under sedation, mechanical ventilation, changes in consciousness [4], or cognitive problems [6] and are hence not able to communicate verbally [7]. Therefore, it is difficult to assess pain in these patients [8]. On the other hand, in the absence of the patient’s own report, change in behavioral and physiological indices can be an important measure for assessing pain [4]. In this regard, three important scales of pain assessment in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in ICUs have been considered in different countries: Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT), Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS), and Non-Verbal Pain Scale (NVPS) [8-19]. While CPOT and BPS scales use behavioral indicators for pain assessment, NVPS uses physiological indicators in addition to behavioral indices [4, 20, 21].

NVPS was introduced in 2003 by Odhner et al. to assess pain in patients admitted to the burn ICU [20]. Their scale had three dimensions: behavioral (facial expression, movement rate, muscle contraction), physiological I (vital signs, heart rate, blood pressure and respiratory rate), and physiological II (dilation of pupils, diaphoretic, flushing, or pallor) [20]. However, later studies have shown that the Autonomic Index (Physiological II) lacks a proper correlation with other dimensions and the whole scale [22-25]. In this regard, NVPS was revised by Kabes et al. in 2009. In the revised version, the autonomic indexes were removed, and the respiratory assessment was replaced by mechanical ventilation and arterial oxygen saturation [22]. The revised NVPS consists of 5 items that are divided into two categories of behavioral (facial expression, movement rate, muscle contraction) and physiological (change in vital signs and respiratory changes) assessment. There are three different modes for each item with a score of 0 to 2, and the total range is between 0 and 10 (in this study, the revised version of NVPS is considered).

Studies have shown that there are ambiguities in some dimensions of NVPS including the physiological I, where vital signs as an indicator for assessing pain lack the necessary validity and reliability [12, 21, 26]. Therefore, due to ambiguities, especially in physiological aspect, more studies are needed to evaluate the validity and reliability of this scale (revised NVPS). On the other hand, any scale that enters a community requires validation of the samples and observations because cultural, social and religious factors can affect pain and suffering [27-30]. In this regard, this study aimed to determine the psychometric properties of revised NVPS in ICUs.

Materials and Methods

This research is a methodological study conducted for NVPS translation and psychometric study. After obtaining permission from the NVPS designer, the scale was first translated to Persian by two English language experts. Then the two translations were compared by the third translator to review and revise the ambiguous cases. The final translation was done by another English language expert, and after verifying the appropriateness of the two translations and confirmation of the final translation, the other stages of the study began. The content validity index was used to measure content validity. For this purpose, ten experts comprising professors in nursing, anesthetists, and nurses working in ICUs were asked to specify the relevance, vividness and simplicity of all five dimensions of NVPS using a point from 1 to 4 [31]. The results showed that content validity index for the whole scale was 0.92.

The study population comprised patients hospitalized in ICUs of three 35-bed hospitals in Ardebil, Iran. Inclusion criteria were being at least 18 years old, being mechanically ventilated for more than 24 hours, having the ability to hear and respond by pointing the head, eyes or eyebrows, gaining scores between -3 to +1 based on the Richmond scale, having a consciousness score of 8 or higher based on the Glasgow Coma Scale, no quadruple paralysis, no extensive damage to the face and arms, no muscle dysfunction, no neuromuscular blocking drug consumption, and non-addiction to alcohol or drugs (based on biography taken from the patient’s family and medical records). During a period of four months, 86 patients entered the study, of which 26 were excluded (9 patients due to extubation of the trachea, 10 patients due to sudden loss of consciousness, and 7 patients due to death or transfer to other centers). Given that at least 5 to 20 subjects per item are required for the analysis of NVPS, 60 patients were sufficient for the assessment.

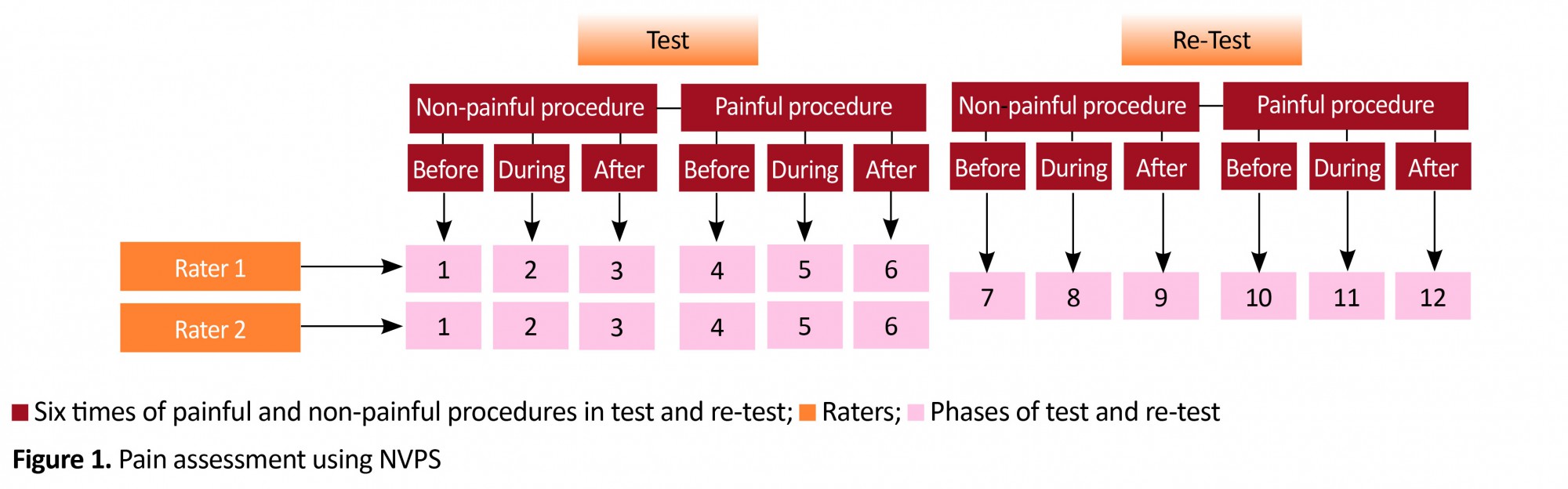

For observing and collecting data, two nurses were determined as raters after receiving six hours of theoretical and two days of practical training on how to complete the questionnaire and research objectives. In each patient, NVPS was evaluated six times by two raters. In each patient, two painful (changing positions) and non-painful procedures (eye wash with normal saline) were used. To assess pain, each patient was observed by two nurses simultaneously but independently. First, the patient was observed three times during non-painful procedures: 15 minutes before (Time 1), during (Time 2), and 15 minutes after the intervention (Time 3). Then, after 20 minutes, the patient was observed three times undergoing painful procedure: 15 minutes before (Time 4), during (Time 5), and 15 minutes after the intervention (Time 6). Due to the complexity of the situation for patients in ICUs, providing the same conditions for the retest is hardly under the control of the raters. Therefore, the test-retest was performed for the second time 8-12 hours later by the main researcher only on 37 participants in the same order. Therefore, 23 patients did not undergo retesting due to lack of proper conditions (Figure 1).

Patients admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICUs) frequently experience pain and discomfort during their stay [1]. Pain continues to be a major stressor in ICUs [2], where it is difficult to assess pain given the presence of illness and life-threatening injuries [3]. Pain assessment is not only the first step in the proper relief of pain but also one of the most important goals in patient care [4]. Since pain is a subjective phenomenon, the most reliable tool for pain assessment is the patient’s own report [5], but most patients in the ICU are under sedation, mechanical ventilation, changes in consciousness [4], or cognitive problems [6] and are hence not able to communicate verbally [7]. Therefore, it is difficult to assess pain in these patients [8]. On the other hand, in the absence of the patient’s own report, change in behavioral and physiological indices can be an important measure for assessing pain [4]. In this regard, three important scales of pain assessment in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in ICUs have been considered in different countries: Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT), Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS), and Non-Verbal Pain Scale (NVPS) [8-19]. While CPOT and BPS scales use behavioral indicators for pain assessment, NVPS uses physiological indicators in addition to behavioral indices [4, 20, 21].

NVPS was introduced in 2003 by Odhner et al. to assess pain in patients admitted to the burn ICU [20]. Their scale had three dimensions: behavioral (facial expression, movement rate, muscle contraction), physiological I (vital signs, heart rate, blood pressure and respiratory rate), and physiological II (dilation of pupils, diaphoretic, flushing, or pallor) [20]. However, later studies have shown that the Autonomic Index (Physiological II) lacks a proper correlation with other dimensions and the whole scale [22-25]. In this regard, NVPS was revised by Kabes et al. in 2009. In the revised version, the autonomic indexes were removed, and the respiratory assessment was replaced by mechanical ventilation and arterial oxygen saturation [22]. The revised NVPS consists of 5 items that are divided into two categories of behavioral (facial expression, movement rate, muscle contraction) and physiological (change in vital signs and respiratory changes) assessment. There are three different modes for each item with a score of 0 to 2, and the total range is between 0 and 10 (in this study, the revised version of NVPS is considered).

Studies have shown that there are ambiguities in some dimensions of NVPS including the physiological I, where vital signs as an indicator for assessing pain lack the necessary validity and reliability [12, 21, 26]. Therefore, due to ambiguities, especially in physiological aspect, more studies are needed to evaluate the validity and reliability of this scale (revised NVPS). On the other hand, any scale that enters a community requires validation of the samples and observations because cultural, social and religious factors can affect pain and suffering [27-30]. In this regard, this study aimed to determine the psychometric properties of revised NVPS in ICUs.

Materials and Methods

This research is a methodological study conducted for NVPS translation and psychometric study. After obtaining permission from the NVPS designer, the scale was first translated to Persian by two English language experts. Then the two translations were compared by the third translator to review and revise the ambiguous cases. The final translation was done by another English language expert, and after verifying the appropriateness of the two translations and confirmation of the final translation, the other stages of the study began. The content validity index was used to measure content validity. For this purpose, ten experts comprising professors in nursing, anesthetists, and nurses working in ICUs were asked to specify the relevance, vividness and simplicity of all five dimensions of NVPS using a point from 1 to 4 [31]. The results showed that content validity index for the whole scale was 0.92.

The study population comprised patients hospitalized in ICUs of three 35-bed hospitals in Ardebil, Iran. Inclusion criteria were being at least 18 years old, being mechanically ventilated for more than 24 hours, having the ability to hear and respond by pointing the head, eyes or eyebrows, gaining scores between -3 to +1 based on the Richmond scale, having a consciousness score of 8 or higher based on the Glasgow Coma Scale, no quadruple paralysis, no extensive damage to the face and arms, no muscle dysfunction, no neuromuscular blocking drug consumption, and non-addiction to alcohol or drugs (based on biography taken from the patient’s family and medical records). During a period of four months, 86 patients entered the study, of which 26 were excluded (9 patients due to extubation of the trachea, 10 patients due to sudden loss of consciousness, and 7 patients due to death or transfer to other centers). Given that at least 5 to 20 subjects per item are required for the analysis of NVPS, 60 patients were sufficient for the assessment.

For observing and collecting data, two nurses were determined as raters after receiving six hours of theoretical and two days of practical training on how to complete the questionnaire and research objectives. In each patient, NVPS was evaluated six times by two raters. In each patient, two painful (changing positions) and non-painful procedures (eye wash with normal saline) were used. To assess pain, each patient was observed by two nurses simultaneously but independently. First, the patient was observed three times during non-painful procedures: 15 minutes before (Time 1), during (Time 2), and 15 minutes after the intervention (Time 3). Then, after 20 minutes, the patient was observed three times undergoing painful procedure: 15 minutes before (Time 4), during (Time 5), and 15 minutes after the intervention (Time 6). Due to the complexity of the situation for patients in ICUs, providing the same conditions for the retest is hardly under the control of the raters. Therefore, the test-retest was performed for the second time 8-12 hours later by the main researcher only on 37 participants in the same order. Therefore, 23 patients did not undergo retesting due to lack of proper conditions (Figure 1).

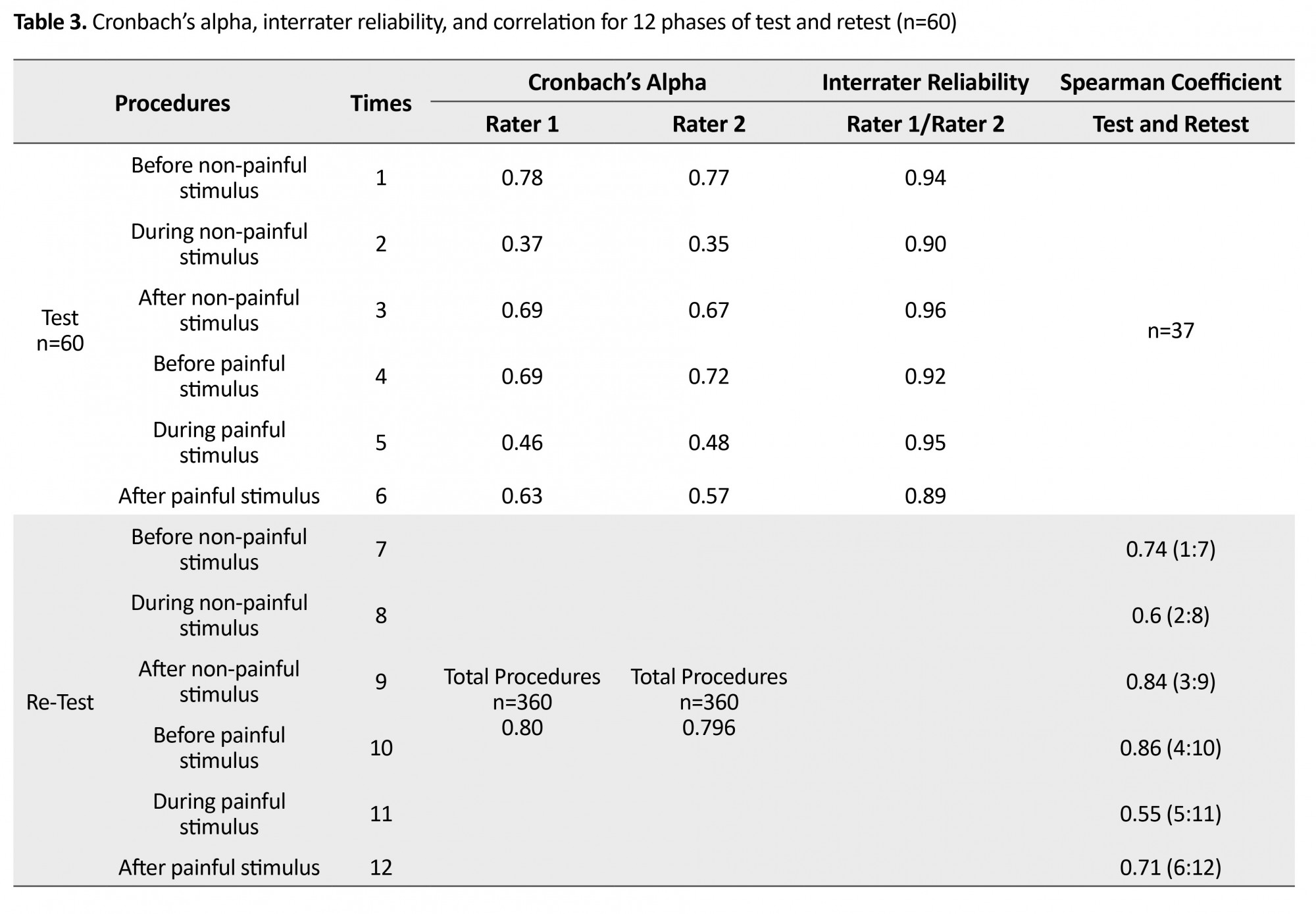

To analyze the data in each case, some proper tests were conducted. To determine discriminant validity, the scores obtained from the observations of first rater were compared in six phases using the Mann-Whitney test (Time 1 compared with Time 4, Time 2 with Time 5, and Time 3 with Time 6). To assess the criterion validity, the standard technique was head and eyebrow movements of patients in response to the presence or absence of pain. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the pain scores in those who had pain with those who reported no pain, and it was expected that if the scale had criterion validity, the pain score in those who had pain was higher than those who did not confirm the presence of pain. The Cronbach's α coefficient was used to determine the internal consistency. Also, to determine the inter-rater reliability of the correlation between scores obtained from two nurses’ observations (raters), Spearman Rho test was used. To determine the test reliability, the Spearman Rho test was used again to check the correlation between test (Time 1 to 6) and retest (Time 7 to 12) scores. It should be mentioned that since the patients were unable to talk, the written consent was received from the patients’ companions.

Results

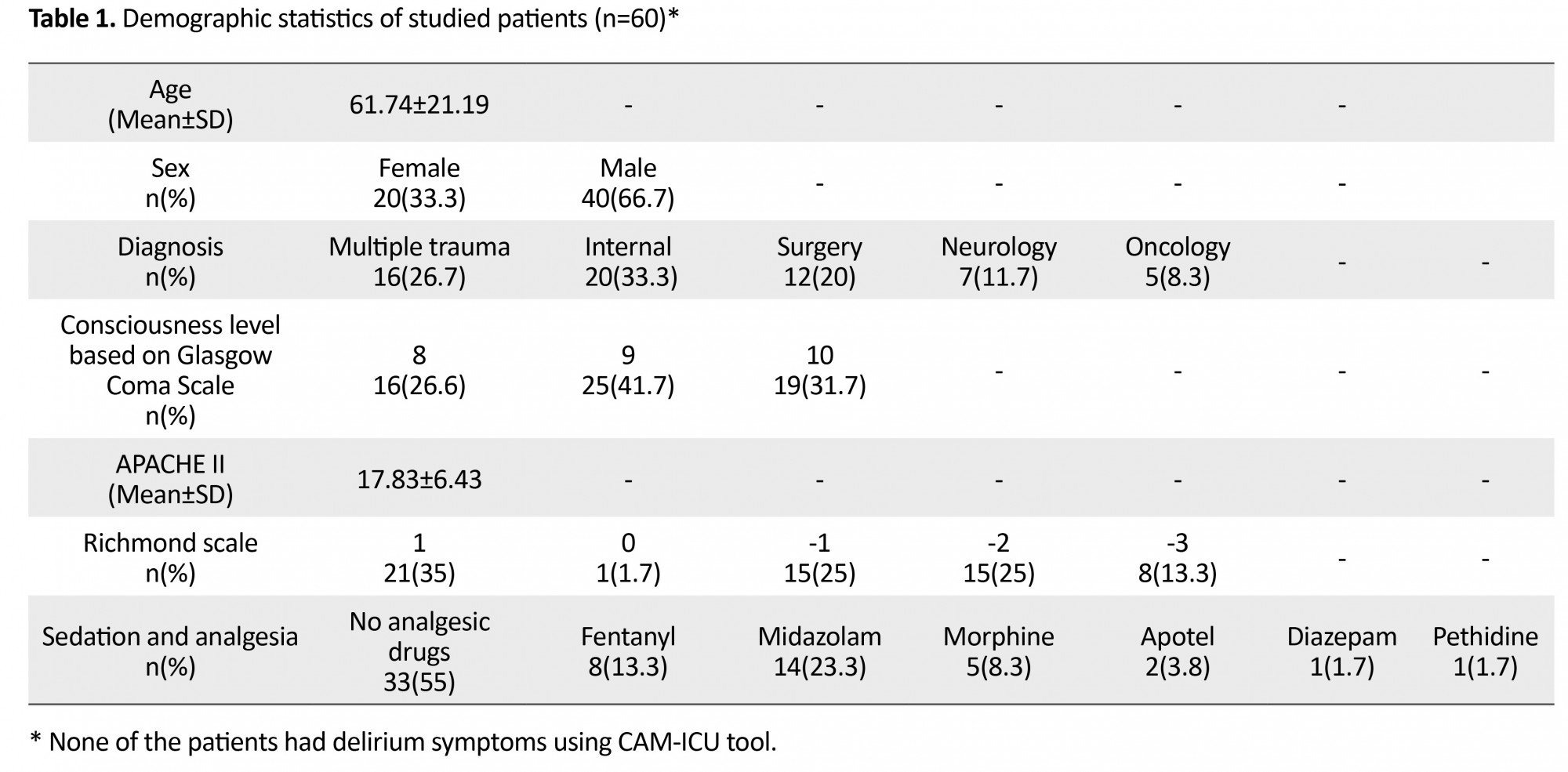

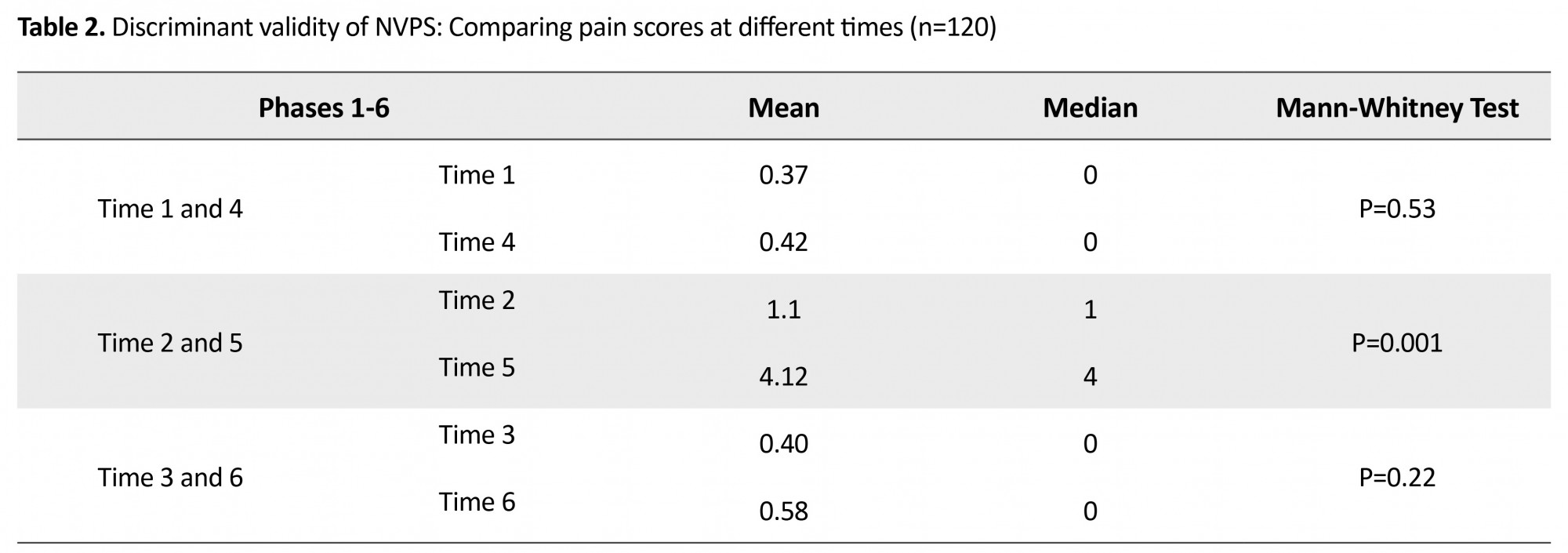

The patients’ demographic data including age, sex, mechanical ventilation, vital signs, APACHE II, and delirium probability were recorded using the CAM-ICU (Confusion Assessment Method for ICU) tool (Table 1). In this study, 360 pairs (720 times) of observation were performed to determine discriminant validity, criterion validity, and interrater reliability, and 222 observations were performed in order to retest (a total of 942 pain observations from 60 patients). With regard to discriminant validity, the Mann-Whitney test results showed that between pain score at Time 1 with Time 4 (before painful and non-painful procedures) and at Time 3 with Time 6 (15 minutes after painful and non-painful procedures), there was no significant difference (P=0.53 and P=0.22, n=120). However, there was a significant difference in pain score during non-painful (Time 2) and painful procedures (Time 5) (P<0.001, n=120). This indicates that the NVPS at the time of painful procedure achieved a higher score than when it was under non-painful procedure (Table 2).

Results

The patients’ demographic data including age, sex, mechanical ventilation, vital signs, APACHE II, and delirium probability were recorded using the CAM-ICU (Confusion Assessment Method for ICU) tool (Table 1). In this study, 360 pairs (720 times) of observation were performed to determine discriminant validity, criterion validity, and interrater reliability, and 222 observations were performed in order to retest (a total of 942 pain observations from 60 patients). With regard to discriminant validity, the Mann-Whitney test results showed that between pain score at Time 1 with Time 4 (before painful and non-painful procedures) and at Time 3 with Time 6 (15 minutes after painful and non-painful procedures), there was no significant difference (P=0.53 and P=0.22, n=120). However, there was a significant difference in pain score during non-painful (Time 2) and painful procedures (Time 5) (P<0.001, n=120). This indicates that the NVPS at the time of painful procedure achieved a higher score than when it was under non-painful procedure (Table 2).

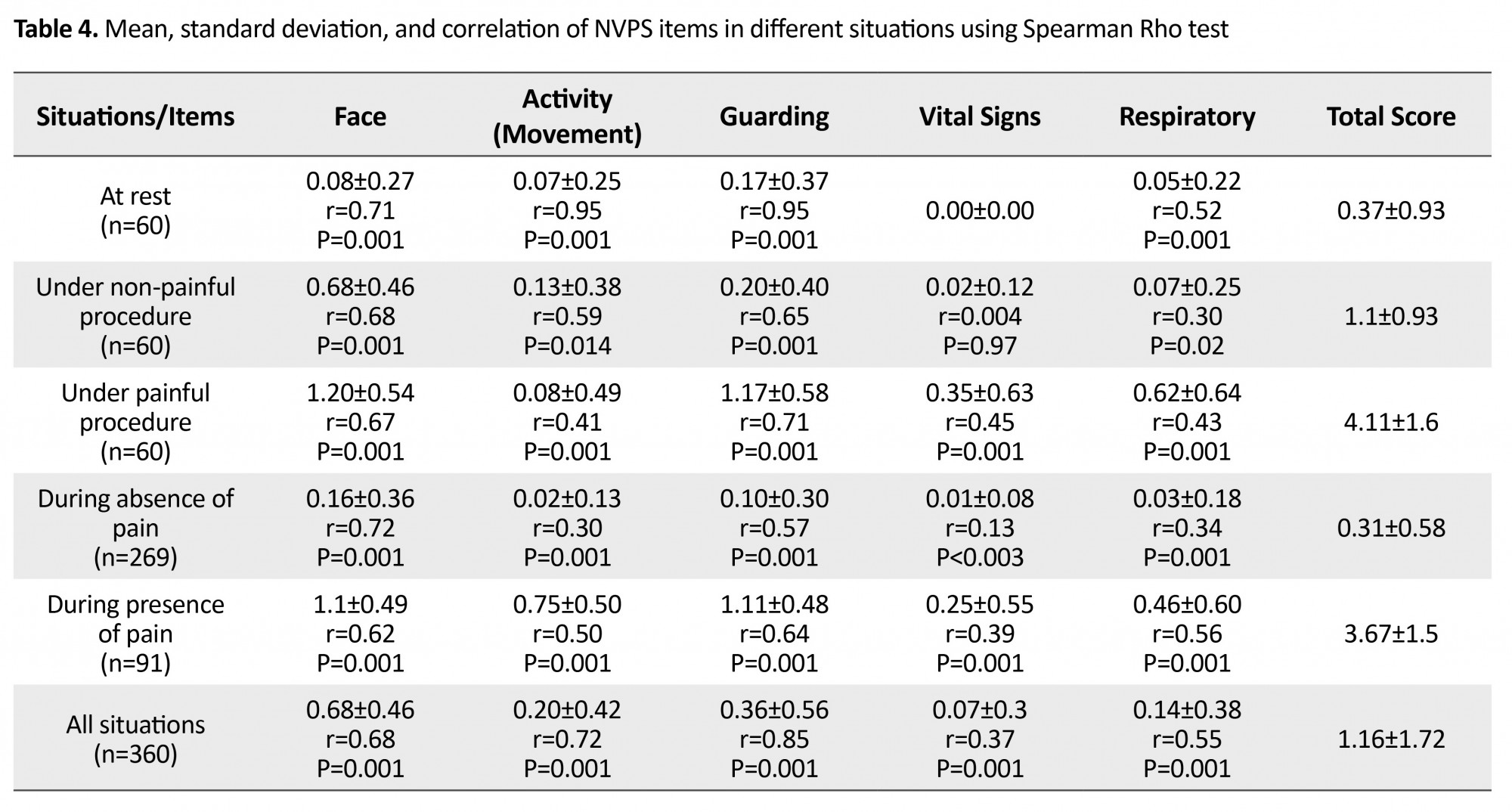

Regarding the evaluation of criterion validity, the patients reported no pain in 269 different situations (mean=0.31, median=0), while in 91 situations, they confirmed the presence of pain (mean=3.67, median=3). The Mann-Whitney test results showed that there was a significant difference in the pain score of the two groups (P=0.001). Among the various items of NVPS, “vital signs” received the lowest change during painful procedure compared to non-painful procedure. The Cronbach's α coefficient for the six different times was reported as 0.80 by the first rater and 0.796 by the second rater (Table 3). The interrater reliability during 6 times of observation as well as correlation results of test and retest are presented in Table 3. In examining the correlation between total and individual item scores of NVPS, the highest and lowest correlations were related to the items of face and vital signs, respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

This research was conducted to study psychometric properties of the revised NVPS among patients admitted to ICUs who could not communicate verbally. Unlike the initial version of NVPS, which was designed and developed based on evaluating burn patients [20], this study was conducted on different patients with maximum variance including internal, surgical, neurological and trauma [10-12, 20, 22]. Criterion validity results showed that those patients who reported pain by head and eyebrow movements had significantly higher pain score in the revised NVPS than those who did not report pain. In their study on trauma and neurosurgical patients, Topolovec-Vranic et al. [12] found out that pain scores were significantly higher for patients who had indicated that they were in pain versus those who were not. This reveals that the revised NVPS has acceptable criterion validity. The results of this study also showed that the total score of revised NVPS was significantly higher during painful nursing procedure (changing positions) compared to when non-painful procedure (eye wash with normal saline) was applied. One of the challenging issues in this study was that during the touch of patients’ face for performing non-painful procedure, the score for the item of facial expression increased significantly but patients did not indicate pain. Other studies also reported the increase in facial expression under non-painful procedure (eye care) [1]. Facial expressions seem to be due to an individual’s defensive response when a foreign object approaches or contacts the eye. In other words, the increase in facial expression during non-painful procedure is an automatic response to the touch, not to the pain.

In measuring the internal consistency of the revised NVPS, an appropriate α coefficient was obtained, but at different situations, especially during painful and non-painful procedures, weak internal consistency was reported. In studies that calculated the Cronbach's α coefficient for the whole scale, α values were reported as “moderate” to “good” [11, 32, 33], but in the study of Kabes et al. [22], α coefficient of revised NVPS was reported as “low” at rest, and “moderate” under painful procedure. One of the reasons that can separately affect the low internal consistency in different situations is the low sample size; in a previous study [22], the sample size was 64, while in the current study, it was 60. The low sample size increases the items’ average variance and, therefore, reduces the Cronbach's α coefficient. On the other hand, the lack of correlation between items in the mentioned situations can also be involved in the low α coefficient. For instance, in the current study, it was found out that the two items of “face expression” and “vital signs” under non-painful nursing procedure and the item “respiratory” under painful procedure had the lowest correlation with other items of NVPS such that by eliminating these items in the mentioned situations, the alpha coefficient increased considerably. Also, in comparing correlation of total and individual item scores of NVPS, the item “vital signs” had the lowest correlation with a total score of NVPS.

Vital signs during rest and non-painful nursing procedure did not change considerably, but under painful procedure and in those patients who indicated pain, these signs increased slightly. One of the most prominent features of NVPS not found in other pain assessment scales is the use of vital signs (including systolic blood pressure changes, heart rate and respiration rate) as a measure of assessment, which makes it easier for nurses to assess pain. However, this item has some challenges, and although vital signs change in the event of pain, they can also be affected by factors other than pain. It seems that the “respiratory” item is also affected in a painful situation by factors other than pain like secretions, hypoxia, ventilation, etc. So further studies are suggested in this regard. Moreover, the results of inter‑rater reliability in this study indicated a good correlation between raters. Some studies in this area show different results. For example, Topolovec-Vranic et al. [12] reported low inter‑rater reliability in all situations except during painful procedure. Others have confirmed our results [10, 11]. Therefore, it can be said that people’s perception of the symptoms of pain in the NVPS is the same, and there is no different interpretation.

Furthermore, the reliability of test‑retest procedure in this study was reported as “good” in all situations except during painful procedure where moderate correlation coefficient was obtained. In this study, a retest was performed 8 to 12 hours later (evening), when patients received higher scores under painful procedure than in the morning test. According to Jankowski [34], due to emotional disturbances and low mood, low cortisol levels and sleep deprivation, patients report more pain in the evening than in the morning. In the field of test reliability in foreign studies, no similar research was found to compare their results; therefore, more studies are needed to test the stability of the test.

In this research, restless patients, those who received neuromuscular blocking drug, or patients with quadruple paralysis were excluded from the study. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to this population, and hence, further studies are needed to assess the pain in these patients. The results of this study showed that the Iranian version of revised NVPS has good and reliable psychometric properties for examining pain in patients admitted to ICUs. However, in using this scale, attention should be paid to several important points, and necessary precautions should be taken in this regard. First, sometimes during the non-painful procedure with a skin or eye touch, the item of facial expression may change, but this does not necessarily indicate pain. In this situation, changes in other items should also be considered. Secondly, the score of the item of vital signs in various actions, especially in cases where pain is reported, does not coincide with other items and shows less variation. In addition, under certain conditions, even without pain, vital signs may be affected by anxiety or fear; in these circumstances, caution should be exercised and the score of other items should be considered.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Since the patients were unable to talk, the written informed consent was received from the patients’ companions.

Funding

This paper was extracted from a MSN thesis in Nursing submitted to Ardabil University of Medical Sciences (IRCTID: IRCT2015062322881NN1). The paper was financially supported by Vice Chancellor for Research of AUMS.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank all patients and their families, personnel of ICUs, and the authorities of Imam Khomeini, Fatemi and Alavi hospitals of Ardebil, the Vice Chancellor for Research of AUMS for financial support, and finally the library staff, and others who helped us with this study.

References

This research was conducted to study psychometric properties of the revised NVPS among patients admitted to ICUs who could not communicate verbally. Unlike the initial version of NVPS, which was designed and developed based on evaluating burn patients [20], this study was conducted on different patients with maximum variance including internal, surgical, neurological and trauma [10-12, 20, 22]. Criterion validity results showed that those patients who reported pain by head and eyebrow movements had significantly higher pain score in the revised NVPS than those who did not report pain. In their study on trauma and neurosurgical patients, Topolovec-Vranic et al. [12] found out that pain scores were significantly higher for patients who had indicated that they were in pain versus those who were not. This reveals that the revised NVPS has acceptable criterion validity. The results of this study also showed that the total score of revised NVPS was significantly higher during painful nursing procedure (changing positions) compared to when non-painful procedure (eye wash with normal saline) was applied. One of the challenging issues in this study was that during the touch of patients’ face for performing non-painful procedure, the score for the item of facial expression increased significantly but patients did not indicate pain. Other studies also reported the increase in facial expression under non-painful procedure (eye care) [1]. Facial expressions seem to be due to an individual’s defensive response when a foreign object approaches or contacts the eye. In other words, the increase in facial expression during non-painful procedure is an automatic response to the touch, not to the pain.

In measuring the internal consistency of the revised NVPS, an appropriate α coefficient was obtained, but at different situations, especially during painful and non-painful procedures, weak internal consistency was reported. In studies that calculated the Cronbach's α coefficient for the whole scale, α values were reported as “moderate” to “good” [11, 32, 33], but in the study of Kabes et al. [22], α coefficient of revised NVPS was reported as “low” at rest, and “moderate” under painful procedure. One of the reasons that can separately affect the low internal consistency in different situations is the low sample size; in a previous study [22], the sample size was 64, while in the current study, it was 60. The low sample size increases the items’ average variance and, therefore, reduces the Cronbach's α coefficient. On the other hand, the lack of correlation between items in the mentioned situations can also be involved in the low α coefficient. For instance, in the current study, it was found out that the two items of “face expression” and “vital signs” under non-painful nursing procedure and the item “respiratory” under painful procedure had the lowest correlation with other items of NVPS such that by eliminating these items in the mentioned situations, the alpha coefficient increased considerably. Also, in comparing correlation of total and individual item scores of NVPS, the item “vital signs” had the lowest correlation with a total score of NVPS.

Vital signs during rest and non-painful nursing procedure did not change considerably, but under painful procedure and in those patients who indicated pain, these signs increased slightly. One of the most prominent features of NVPS not found in other pain assessment scales is the use of vital signs (including systolic blood pressure changes, heart rate and respiration rate) as a measure of assessment, which makes it easier for nurses to assess pain. However, this item has some challenges, and although vital signs change in the event of pain, they can also be affected by factors other than pain. It seems that the “respiratory” item is also affected in a painful situation by factors other than pain like secretions, hypoxia, ventilation, etc. So further studies are suggested in this regard. Moreover, the results of inter‑rater reliability in this study indicated a good correlation between raters. Some studies in this area show different results. For example, Topolovec-Vranic et al. [12] reported low inter‑rater reliability in all situations except during painful procedure. Others have confirmed our results [10, 11]. Therefore, it can be said that people’s perception of the symptoms of pain in the NVPS is the same, and there is no different interpretation.

Furthermore, the reliability of test‑retest procedure in this study was reported as “good” in all situations except during painful procedure where moderate correlation coefficient was obtained. In this study, a retest was performed 8 to 12 hours later (evening), when patients received higher scores under painful procedure than in the morning test. According to Jankowski [34], due to emotional disturbances and low mood, low cortisol levels and sleep deprivation, patients report more pain in the evening than in the morning. In the field of test reliability in foreign studies, no similar research was found to compare their results; therefore, more studies are needed to test the stability of the test.

In this research, restless patients, those who received neuromuscular blocking drug, or patients with quadruple paralysis were excluded from the study. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to this population, and hence, further studies are needed to assess the pain in these patients. The results of this study showed that the Iranian version of revised NVPS has good and reliable psychometric properties for examining pain in patients admitted to ICUs. However, in using this scale, attention should be paid to several important points, and necessary precautions should be taken in this regard. First, sometimes during the non-painful procedure with a skin or eye touch, the item of facial expression may change, but this does not necessarily indicate pain. In this situation, changes in other items should also be considered. Secondly, the score of the item of vital signs in various actions, especially in cases where pain is reported, does not coincide with other items and shows less variation. In addition, under certain conditions, even without pain, vital signs may be affected by anxiety or fear; in these circumstances, caution should be exercised and the score of other items should be considered.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Since the patients were unable to talk, the written informed consent was received from the patients’ companions.

Funding

This paper was extracted from a MSN thesis in Nursing submitted to Ardabil University of Medical Sciences (IRCTID: IRCT2015062322881NN1). The paper was financially supported by Vice Chancellor for Research of AUMS.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank all patients and their families, personnel of ICUs, and the authorities of Imam Khomeini, Fatemi and Alavi hospitals of Ardebil, the Vice Chancellor for Research of AUMS for financial support, and finally the library staff, and others who helped us with this study.

References

- Young J, Siffleet J, Nikoletti S, Shaw T. Use of a Behavioural Pain Scale to assess pain in ventilated, unconscious and/or sedated patients. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2006; 22(1):32-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2005.04.004]

- Urden LD, Stacy KM, Lough ME. Critical care nursing, diagnosis and management: Critical care nursing. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013. [PMID]

- Topolovec-Vranic J, Canzian S, Innis J, Pollmann-Mudryj MA, McFarlan AW, Baker AJ. Patient satisfaction and documentation of pain assessments and management after implementing the adult nonverbal pain scale. American Journal of Critical Care. 2010; 19(4):345-54. [DOI:10.4037/ajcc2010247]

- Gélinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, Viens C, Fortier M. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. American Journal of Critical Care. 2006; 15(4):420-7. [DOI:10.1037/t33641-000]

- Arbour C, Gélinas C, Michaud C. Impact of the implementation of the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) on pain management and clinical outcomes in mechanically ventilated trauma intensive care unit patients: A pilot study. Journal of Trauma Nursing. 2011; 18(1):52-60. [DOI:10.1097/JTN.0b013e3181ff2675]

- Gélinas C, Ross M, Boitor M, Desjardins S, Vaillant F, Michaud C. Nurses’ evaluations of the CPOT use at 12-month post-implementation in the intensive care unit. Nursing in Critical Care. 2014; 19(6):272-80. [DOI:10.1111/nicc.12084]

- Herr K, Coyne PJ, Key T, Manworren R, McCaffery M, Merkel S, et al. Pain assessment in the nonverbal patient: Position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Management Nursing. 2006; 7(2):44-52. [DOI:10.1016/j.pmn.2006.02.003] [PMID]

- Rijkenberg S, Stilma W, Endeman H, Bosman R, Oudemans-van Straaten H. Pain measurement in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: Behavioral Pain Scale versus Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool. Journal of Critical Care. 2015; 30(1):167-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.007] [PMID]

- Chookalayia H, Heidarzadeh M, Hassanpour-Darghah M, Aghamohammadi-Kalkhoran M, Karimollahi M. The critical care pain observation tool is reliable in non-agitated but not in agitated intubated patients. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2018; 44:123-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2017.07.012] [PMID]

- Chanques G, Pohlman A, Kress JP, Molinari N, De Jong A, Jaber S, et al. Psychometric comparison of three behavioural scales for the assessment of pain in critically ill patients unable to self-report. Critical Care. 2014; 18:R160. [DOI:10.1186/cc14000] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Juarez P, Bach A, Baker M, Duey D, Durkin S, Gulczynski B, et al. Comparison of two pain scales for the assessment of pain in the ventilated adult patient. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2010; 29(6):307-15. [DOI:10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181f0c48f] [PMID]

- Topolovec-Vranic J, Gélinas C, Li Y, Pollmann-Mudryj MA, Innis J, McFarlan A, et al. Validation and evaluation of two observational pain assessment tools in a trauma and neurosurgical intensive care unit. Pain Research & Management: The Journal of the Canadian Pain Society. 2013; 18(6):e107.

- Chen YY, Lai YH, Shun SC, Chi NH, Tsai PS, Liao YM. The Chinese behavior pain scale for critically ill patients: Translation and psychometric testing. International Journal of nursing studies. 2011; 48(4):438-48. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.07.016] [PMID]

- Aïssaoui Y, Zeggwagh AA, Zekraoui A, Abidi K, Abouqal R. Validation of a behavioral pain scale in critically ill, sedated, and mechanically ventilated patients. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2005; 101(5):1470-6. [DOI:10.1213/01.ANE.0000182331.68722.FF] [PMID]

- Ahlers SJ, van der Veen AM, van Dijk M, Tibboel D, Knibbe CA. The use of the behavioral pain scale to assess pain in conscious sedated patients. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2010; 110(1):127-33. [DOI:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c3119e] [PMID]

- Keane KM. Validity and reliability of the critical care pain observation tool: A replication study. Pain Management Nursing. 2013; 14(4):e216-e25. [DOI:10.1016/j.pmn.2012.01.002] [PMID]

- Li Q, Wan X, Gu C, Yu Y, Huang W, Li S, et al. Pain assessment using the critical-care pain observation tool in Chinese critically ill ventilated adults. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2014; 48(5):975-82. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.01.014] [PMID]

- Nürnberg Damström D, Saboonchi F, Sackey P, Björling G. A preliminary validation of the Swedish version of the critical-care pain observation tool in adults. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2011; 55(4):379-86. [DOI:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02376.x] [PMID]

- Heidarzadeh M, Jabrailzadeh S, Chookalayi H, Kohi F. [Translation and psychometrics of the "behavioral pain scale" in mechanically ventilated patients in medical and surgical intensive care units (Persian)]. Journal of Urmia Nursing And Midwifery Faculty. 2017; 15(3):176-86.

- Odhner M, Wegman D, Freeland N, Steinmetz A, Ingersoll GL. Assessing pain control in nonverbal critically ill adults. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2003; 22(6):260-7. [DOI:10.1097/00003465-200311000-00010] [PMID]

- Payen JF, Bru O, Bosson JL, Lagrasta A, Novel E, Deschaux I, et al. Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Critical Care Medicine. 2001; 29(12):2258-63. [DOI:10.1097/00003246-200112000-00004]

- Kabes AM, Graves JK, Norris J. Further validation of the nonverbal pain scale in intensive care patients. Critical Care Nurse. 2009; 29(1):59-66. [DOI:10.4037/ccn2009992] [PMID]

- Odhner M, Wegman D, Freeland N, Ingersoll G. Evaluation of a newly developed non-verbal pain scale (NVPS) for assessment of pain in sedated critically ill patients [Internet]. 2004 [Accessed 22 November 2004]. Available from: http://www.aacn.org/AACN/NTIPoster.nsf/vwdoc/2004NTI

- Wegman DA. Tool for pain assessment. Critical Care Nurse. 2005; 25(1):14-5. [PMID]

- Chookalayi H, Heidarzadeh M, Hasanpour M, Jabrailzadeh S, Sadeghpour F. A study on the psychometric properties of revised-nonverbal pain scale and original-nonverbal pain scale in Iranian nonverbal-ventilated patients. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 2017; 21(7):429–435. [DOI:10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_114_17] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Arbour C, Gélinas C. Are vital signs valid indicators for the assessment of pain in postoperative cardiac surgery ICU adults. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2010; 26(2):83-90. [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2009.11.003] [PMID]

- Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P, Speck P, Higginson I. Cultural meanings of pain: A qualitative study of Black Caribbean and White British patients with advanced cancer. Palliative Medicine. 2008; 22(4):350-9. [DOI:10.1177/0269216308090168] [PMID]

- Perez JE, Forero-Puerta T, Palesh O, Lubega S, Thoresen C, Bowman E, et al. Pain, distress, and social support in relation to spiritual beliefs and experiences among persons living with HIV/AIDS. In: Upton JC, editors. Religion and Psychology: New Research. New York: Nova Science; 2008.

- Delgado-Guay MO, Hui D, Parsons HA, Govan K, De la Cruz M, Thorney S, et al. Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011; 41(6):986-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.017] [PMID]

- Chen LM, Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Pantilat S. Concepts within the Chinese culture that influence the cancer pain experience. Cancer Nursing. 2008; 31(2):103-8. [DOI:10.1097/01.NCC.0000305702.07035.4d] [PMID]

- Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007; 30(4):459-67. [DOI:10.1002/nur.20199] [PMID]

- Marmo L, Fowler S. Pain assessment tool in the critically ill post–open heart surgery patient population. Pain Management Nursing. 2010; 11(3):134-40. [DOI:10.1016/j.pmn.2009.05.007] [PMID]

- Wibbenmeyer L, Sevier A, Liao J, Williams I, Latenser B, Robert Lewis I, et al. Evaluation of the usefulness of two established pain assessment tools in a burn population. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2011; 32(1):52-60. [DOI:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182033359] [PMID]

- Jankowski K. Morning types are less sensitive to pain than evening types all day long. European Journal of Pain. 2013; 17(7):1068-73. [DOI:10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00274.x] [PMID]

Article Type : Applicable |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2015/11/23 | Accepted: 2018/06/30 | Published: 2018/06/15

Received: 2015/11/23 | Accepted: 2018/06/30 | Published: 2018/06/15

References

1. Young J, Siffleet J, Nikoletti S, Shaw T. Use of a Behavioural Pain Scale to assess pain in ventilated, unconscious and/or sedated patients. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2006; 22(1):32-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2005.04.004] [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2005.04.004]

2. Urden LD, Stacy KM, Lough ME. Critical care nursing, diagnosis and management: Critical care nursing. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013. [PMID] [PMID]

3. Topolovec-Vranic J, Canzian S, Innis J, Pollmann-Mudryj MA, McFarlan AW, Baker AJ. Patient satisfaction and documentation of pain assessments and management after implementing the adult nonverbal pain scale. American Journal of Critical Care. 2010; 19(4):345-54. [DOI:10.4037/ajcc2010247] [DOI:10.4037/ajcc2010247]

4. Gélinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, Viens C, Fortier M. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. American Journal of Critical Care. 2006; 15(4):420-7. [DOI:10.1037/t33641-000] [DOI:10.1037/t33641-000]

5. Arbour C, Gélinas C, Michaud C. Impact of the implementation of the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) on pain management and clinical outcomes in mechanically ventilated trauma intensive care unit patients: A pilot study. Journal of Trauma Nursing. 2011; 18(1):52-60. [DOI:10.1097/JTN.0b013e3181ff2675] [DOI:10.1097/JTN.0b013e3181ff2675]

6. Gélinas C, Ross M, Boitor M, Desjardins S, Vaillant F, Michaud C. Nurses' evaluations of the CPOT use at 12-month post-implementation in the intensive care unit. Nursing in Critical Care. 2014; 19(6):272-80. [DOI:10.1111/nicc.12084] [DOI:10.1111/nicc.12084]

7. Herr K, Coyne PJ, Key T, Manworren R, McCaffery M, Merkel S, et al. Pain assessment in the nonverbal patient: Position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Management Nursing. 2006; 7(2):44-52. [DOI:10.1016/j.pmn.2006.02.003] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.pmn.2006.02.003]

8. Rijkenberg S, Stilma W, Endeman H, Bosman R, Oudemans-van Straaten H. Pain measurement in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: Behavioral Pain Scale versus Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool. Journal of Critical Care. 2015; 30(1):167-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.007] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.007]

9. Chookalayia H, Heidarzadeh M, Hassanpour-Darghah M, Aghamohammadi-Kalkhoran M, Karimollahi M. The critical care pain observation tool is reliable in non-agitated but not in agitated intubated patients. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2018; 44:123-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2017.07.012] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2017.07.012]

10. Chanques G, Pohlman A, Kress JP, Molinari N, De Jong A, Jaber S, et al. Psychometric comparison of three behavioural scales for the assessment of pain in critically ill patients unable to self-report. Critical Care. 2014; 18:R160. [DOI:10.1186/cc14000] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1186/cc14000]

11. Juarez P, Bach A, Baker M, Duey D, Durkin S, Gulczynski B, et al. Comparison of two pain scales for the assessment of pain in the ventilated adult patient. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2010; 29(6):307-15. [DOI:10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181f0c48f] [PMID] [DOI:10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181f0c48f]

12. Topolovec-Vranic J, Gélinas C, Li Y, Pollmann-Mudryj MA, Innis J, McFarlan A, et al. Validation and evaluation of two observational pain assessment tools in a trauma and neurosurgical intensive care unit. Pain Research & Management: The Journal of the Canadian Pain Society. 2013; 18(6):e107.

13. Chen YY, Lai YH, Shun SC, Chi NH, Tsai PS, Liao YM. The Chinese behavior pain scale for critically ill patients: Translation and psychometric testing. International Journal of nursing studies. 2011; 48(4):438-48. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.07.016] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.07.016]

14. Aïssaoui Y, Zeggwagh AA, Zekraoui A, Abidi K, Abouqal R. Validation of a behavioral pain scale in critically ill, sedated, and mechanically ventilated patients. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2005; 101(5):1470-6. [DOI:10.1213/01.ANE.0000182331.68722.FF] [PMID] [DOI:10.1213/01.ANE.0000182331.68722.FF]

15. Ahlers SJ, van der Veen AM, van Dijk M, Tibboel D, Knibbe CA. The use of the behavioral pain scale to assess pain in conscious sedated patients. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2010; 110(1):127-33. [DOI:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c3119e] [PMID] [DOI:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c3119e]

16. Keane KM. Validity and reliability of the critical care pain observation tool: A replication study. Pain Management Nursing. 2013; 14(4):e216-e25. [DOI:10.1016/j.pmn.2012.01.002] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.pmn.2012.01.002]

17. Li Q, Wan X, Gu C, Yu Y, Huang W, Li S, et al. Pain assessment using the critical-care pain observation tool in Chinese critically ill ventilated adults. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2014; 48(5):975-82. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.01.014] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.01.014]

18. Nürnberg Damström D, Saboonchi F, Sackey P, Björling G. A preliminary validation of the Swedish version of the critical-care pain observation tool in adults. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2011; 55(4):379-86. [DOI:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02376.x] [PMID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02376.x]

19. Heidarzadeh M, Jabrailzadeh S, Chookalayi H, Kohi F. [Translation and psychometrics of the "behavioral pain scale" in mechanically ventilated patients in medical and surgical intensive care units (Persian)]. Journal of Urmia Nursing And Midwifery Faculty. 2017; 15(3):176-86.

20. Odhner M, Wegman D, Freeland N, Steinmetz A, Ingersoll GL. Assessing pain control in nonverbal critically ill adults. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2003; 22(6):260-7. [DOI:10.1097/00003465-200311000-00010] [PMID] [DOI:10.1097/00003465-200311000-00010]

21. Payen JF, Bru O, Bosson JL, Lagrasta A, Novel E, Deschaux I, et al. Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Critical Care Medicine. 2001; 29(12):2258-63. [DOI:10.1097/00003246-200112000-00004] [DOI:10.1097/00003246-200112000-00004]

22. Kabes AM, Graves JK, Norris J. Further validation of the nonverbal pain scale in intensive care patients. Critical Care Nurse. 2009; 29(1):59-66. [DOI:10.4037/ccn2009992] [PMID] [DOI:10.4037/ccn2009992]

23. Odhner M, Wegman D, Freeland N, Ingersoll G. Evaluation of a newly developed non-verbal pain scale (NVPS) for assessment of pain in sedated critically ill patients [Internet]. 2004 [Accessed 22 November 2004]. Available from: http://www.aacn.org/AACN/NTIPoster.nsf/vwdoc/2004NTI

24. Wegman DA. Tool for pain assessment. Critical Care Nurse. 2005; 25(1):14-5. [PMID] [PMID]

25. Chookalayi H, Heidarzadeh M, Hasanpour M, Jabrailzadeh S, Sadeghpour F. A study on the psychometric properties of revised-nonverbal pain scale and original-nonverbal pain scale in Iranian nonverbal-ventilated patients. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 2017; 21(7):429–435. [DOI:10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_114_17] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_114_17]

26. Arbour C, Gélinas C. Are vital signs valid indicators for the assessment of pain in postoperative cardiac surgery ICU adults. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2010; 26(2):83-90. [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2009.11.003] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2009.11.003]

27. Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P, Speck P, Higginson I. Cultural meanings of pain: A qualitative study of Black Caribbean and White British patients with advanced cancer. Palliative Medicine. 2008; 22(4):350-9. [DOI:10.1177/0269216308090168] [PMID] [DOI:10.1177/0269216308090168]

28. Perez JE, Forero-Puerta T, Palesh O, Lubega S, Thoresen C, Bowman E, et al. Pain, distress, and social support in relation to spiritual beliefs and experiences among persons living with HIV/AIDS. In: Upton JC, editors. Religion and Psychology: New Research. New York: Nova Science; 2008.

29. Delgado-Guay MO, Hui D, Parsons HA, Govan K, De la Cruz M, Thorney S, et al. Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011; 41(6):986-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.017] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.017]

30. Chen LM, Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Pantilat S. Concepts within the Chinese culture that influence the cancer pain experience. Cancer Nursing. 2008; 31(2):103-8. [DOI:10.1097/01.NCC.0000305702.07035.4d] [PMID] [DOI:10.1097/01.NCC.0000305702.07035.4d]

31. Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007; 30(4):459-67. [DOI:10.1002/nur.20199] [PMID] [DOI:10.1002/nur.20199]

32. Marmo L, Fowler S. Pain assessment tool in the critically ill post–open heart surgery patient population. Pain Management Nursing. 2010; 11(3):134-40. [DOI:10.1016/j.pmn.2009.05.007] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.pmn.2009.05.007]

33. Wibbenmeyer L, Sevier A, Liao J, Williams I, Latenser B, Robert Lewis I, et al. Evaluation of the usefulness of two established pain assessment tools in a burn population. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2011; 32(1):52-60. [DOI:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182033359] [PMID] [DOI:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182033359]

34. Jankowski K. Morning types are less sensitive to pain than evening types all day long. European Journal of Pain. 2013; 17(7):1068-73. [DOI:10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00274.x] [PMID] [DOI:10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00274.x]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |