Wed, Jan 28, 2026

Volume 36, Issue 1 (1-2026)

JHNM 2026, 36(1): 37-45 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Houshyari khah H, mirhadian L, pourbagheri S, Maroufizadeh S, Shayesteh Fard M. Self-management status and its associated factors among rural patients with type 2 diabetes in Guilan Province, North of Iran. JHNM 2026; 36 (1) :37-45

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2605-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2605-en.html

Hojjat Houshyari khah1

, Leila Mirhadian1

, Leila Mirhadian1

, Sajad Pourbagheri2

, Sajad Pourbagheri2

, Saman Maroufizadeh3

, Saman Maroufizadeh3

, Marzieh Shayesteh Fard *4

, Marzieh Shayesteh Fard *4

, Leila Mirhadian1

, Leila Mirhadian1

, Sajad Pourbagheri2

, Sajad Pourbagheri2

, Saman Maroufizadeh3

, Saman Maroufizadeh3

, Marzieh Shayesteh Fard *4

, Marzieh Shayesteh Fard *4

1- Instructor, Department of nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Nursing (MSN), Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,marziehshayestehfard@gmail.com

2- Nursing (MSN), Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 553 kb]

(50 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (96 Views)

Full-Text: (4 Views)

Introduction

Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) is a chronic and progressively burdensome condition that can significantly affect patients and the health systems [1]. Statistics show that the prevalence of this disease in Iran is 4.11%, and approximately 4 million people are infected [2]. Guilan Province has shown the highest prevalence of T2D (18.9%) in Iran, with a prediabetes prevalence of 18.2% [3]. In Iran, the prevalence is notably higher in rural areas—approximately 17% more than in urban regions [4]. Globally, it is estimated that around 12% of total health expenditures are spent on treating T2D and its complications, with countries allocating between 5-20% of their national health budgets to combating this disease [5]. In Iran, the annual negative economic burden of diabetes has been estimated at over 3.78 billion USD [6, 7].

Effective diabetes management is achievable through self-care behaviours and ongoing self-management [4]. Diabetes self-management encompasses the ongoing, independent practices adopted by individuals with or at risk of diabetes to learn how to live with the disease, effectively manage their conditions, and control the potential complications [8]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) emphasizes that patients should actively participate in self-care [9]. It includes a healthy diet, physical activity, glucose monitoring, appropriate medication, problem-solving beliefs, adaptation skills, and risk-mitigation behaviours [8]. Given the lifelong nature of diabetes management, patient education and self-management support are essential components of diabetes care. To improve clinical outcomes and Quality of Life (QoL), various health systems, including Iran, have implemented comprehensive diabetes self-management programs [9]. Iran’s National Program for Prevention and Control of Diabetes (NPPCD) aligns with this self-management approach, focusing on early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, continuous care, and the prevention of complications [10-12]. This program aims to help patients maintain near-normal blood glucose levels and prevent disease-related complications [7, 13].

The findings of studies on the effectiveness of diabetes self-management programs in rural areas are contradictory. Some studies report inadequate self-care behaviours [7, 8, 13], some showed limited attempts to change unhealthy habits unless severe symptoms are present, and some demonstrated low engagement in overall self-care. Many rural patients fail to meet care objectives [12], underestimate disease severity, exhibit poor treatment adherence, and achieve target Haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in only about half of cases [7, 12]. Given the influence of cultural, social, and economic factors on self-management behaviours and the paucity of research on rural settings in Iran, the present study aimed to investigate the status of diabetes self-management and its associated factors among patients with T2D in rural areas of Guilan Province, north of Iran.

Materials and Methods

This analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in 2023 on 350 patients with T2D residing in rural areas of Guilan Province, Iran. Participants were selected using stratified, cluster, and convenience sampling methods from those enrolled in the NPPCD. Rural comprehensive health centers in Bandar Anzali, Guilan Province, were stratified into western and eastern centers as clusters. Then, 2–4 health centers were randomly selected from each cluster using a random number table. Finally, a convenience sample was used to select participants from the selected health centers. The study was conducted across three rural comprehensive health service centers and 16 affiliated health houses in the county. These centers provide regular care and diabetes education, led by trained community health workers, including periodic health assessments and laboratory tests. Inclusion criteria were age over 30 years, at least six months of diagnosed T2D, receiving training from the community health workers in accordance with NPPCD, regular performance of clinical lab tests including HbA1c and Fasting Blood Sugar (FBS) tests, at least two consecutive face-to-face visits to health houses for follow-up, informed consent, no mental or cognitive disorders, no visual or hearing impairments, no hospitalizations during the study due to diabetes complications, and no gestational diabetes, type 1 diabetes, cancer, or other disabling conditions requiring home care.

Data collection was performed by a structured questionnaire consisting of three sections: (A) a socio-economic/demographic form surveying age, sex, marital status, job, level of education, income, number of family members, diabetes duration, family history, and history of smoking; (B) a clinical profile form measuring anthropometric factors (height, weight, Body Mass Index [BMI]), physiological factors (blood pressure), and biochemical factors (FBS and HbA1c; HbA1c <7% indicating good glycaemic control, and ≥7% representing poor glycaemic control [14]); (C) The Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire - Revised (DSMQ-R), developed by Schmitt et al. [15-17]. We used its Persian version validated by Hosseinzadegan et al [18]. The DSMQ-R evaluates diabetes self-management practices in the past 8 weeks. It has two versions: A 20-item version for patients treated with oral antidiabetic medications and a 27-item version for those on insulin therapy. Both versions were used in this study. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (does not apply to me) to 3 (applies to me very much), assessing self-management in the following domains: Eating behavior, glucose monitoring, physical activity, and cooperation with the diabetes team. Scoring involved summing up the scores for each domain, and then transforming it to a scale range 1-10. Higher scores indicate more favorable self-management practices. In developing countries, 75% of participants score below the desired level of self-management. Consequently, in this study, scores ≥6 indicate favorable self-management, while scores <6 indicate unfavorable self-management [19, 20]. In our study, the reliability of the DSMQ-R was assessed among 30 participants. Cronbach’s α values were 0.844 for the 20-item version and 0.778 for the 27-item version, indicating acceptable internal consistency.

Data collection was carried out from March to June 2023. The researcher completed the socio-economic/demographic and DSMQ-R questionnaires via face-to-face interview. The clinical profile form was completed based on the patients’ registered health records. Statistical analysis was performed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Quantitative data were presented as Mean±SD and qualitative data as frequency (percentage). The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, graphical plots, and skewness and kurtosis indices. For univariate analyses, parametric tests (including independent t-test, one-way ANOVA, and Pearson’s correlation test) or their non-parametric equivalents (Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis, and Spearman’s correlation test) were applied. The multivariate analysis was conducted using multiple linear regression. All analyses were conducted in SPSS software, version 16. The statistically significant level was set at 0.05.

Results

In this study, the majority of participants were female (55.4%), housewives (50.3%), married (70.9%), with lower than high school education (54.9%), low income (74.9%), and with a family history of diabetes (79.7%) (Table 1).

The mean age of participants was 59±6.96 years; their mean BMI, 26.98±2.72 kg/m2; and their mean systolic blood pressure, 131.11±6.47 mm Hg. Most patients had 2-3 comorbid diseases.

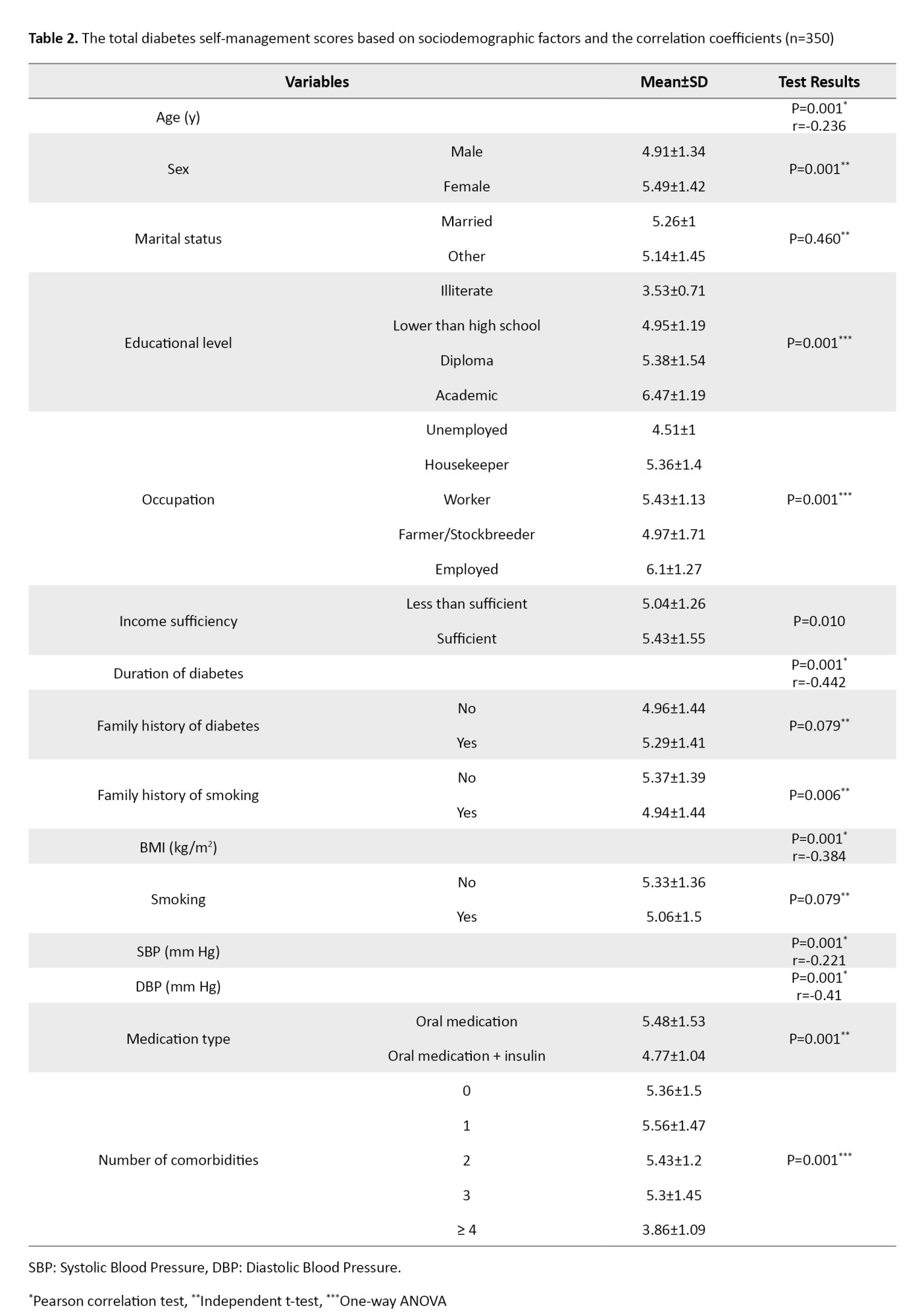

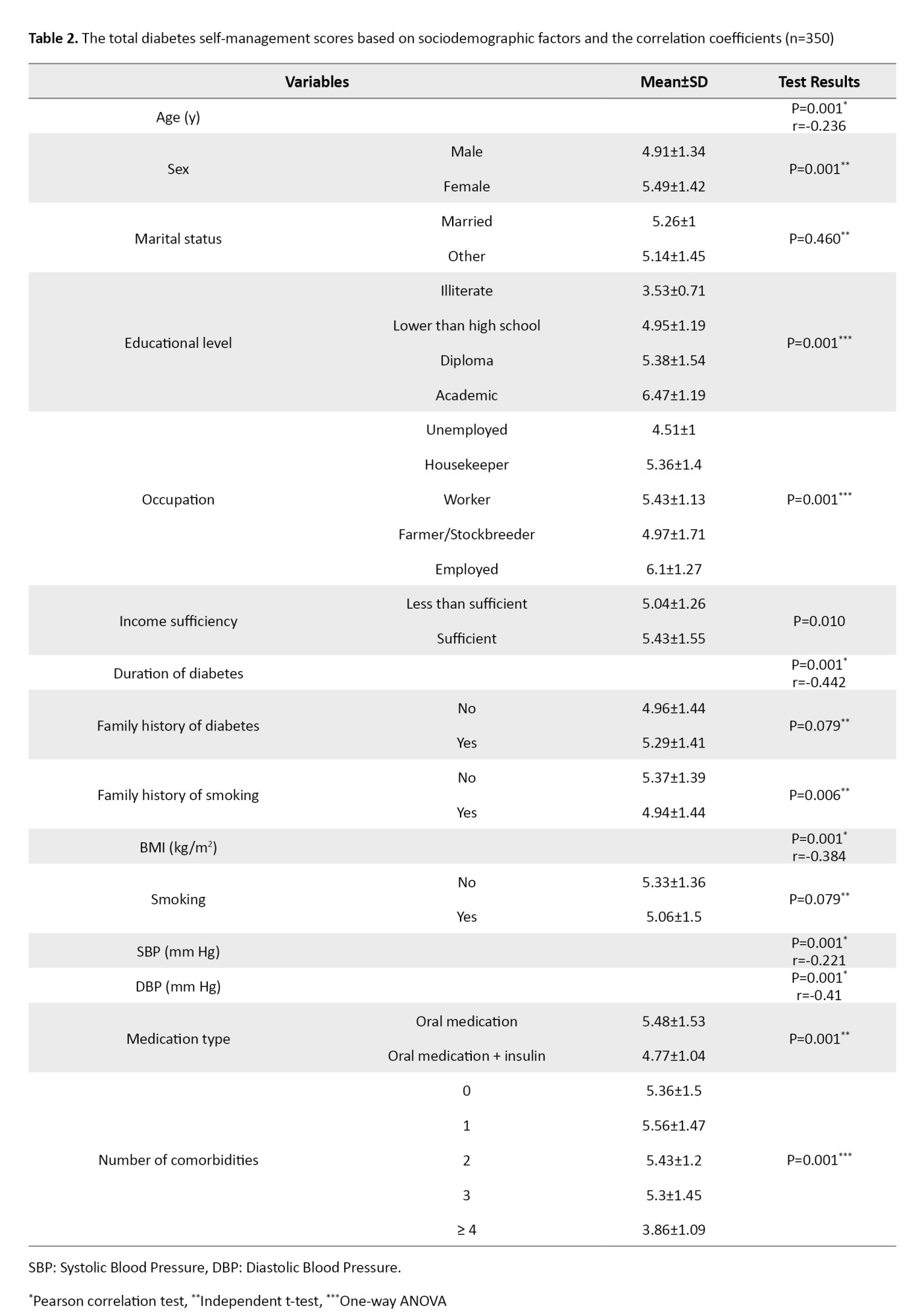

The total mean DSMQ-R score was 5.23±1.42. There was a significant difference in the mean scores of the DSMQ-R domains based on the independent t-test results. The glucose monitoring domain had a score higher than that of other domains (5.99±1.57, P=0.001). The mean scores for eating behavior (5.28±2.05) and cooperation with the diabetes team (5.35±1.55) domains were significantly higher than that of the physical activity domain (3.87±2.06) (P=0.001). The total DSMQ-R score had a significant negative correlation with age (r=-0.23, P=0.001), diabetes duration (r=-0.44, P=0.001), BMI (r=-0.38, P=0.001), systolic blood pressure (r=-0.22, P=0.001), and diastolic blood pressure (r=-0.41, P=0.001) according to the Pearson correlation test results. According to independent t-test results, there were significant differences in total DSMQ-R score based on sex and type of medication (P=0.001), where the scores were higher in females than in males, and lower in those using insulin plus oral medications than in those using only oral medications (P=0.001). Significant differences in total DSMQ-R scores were also observed based on education level (P=0.001) and number of comorbidities (P=0.001), according to one-way ANOVA results. These results were shown in Table 2.

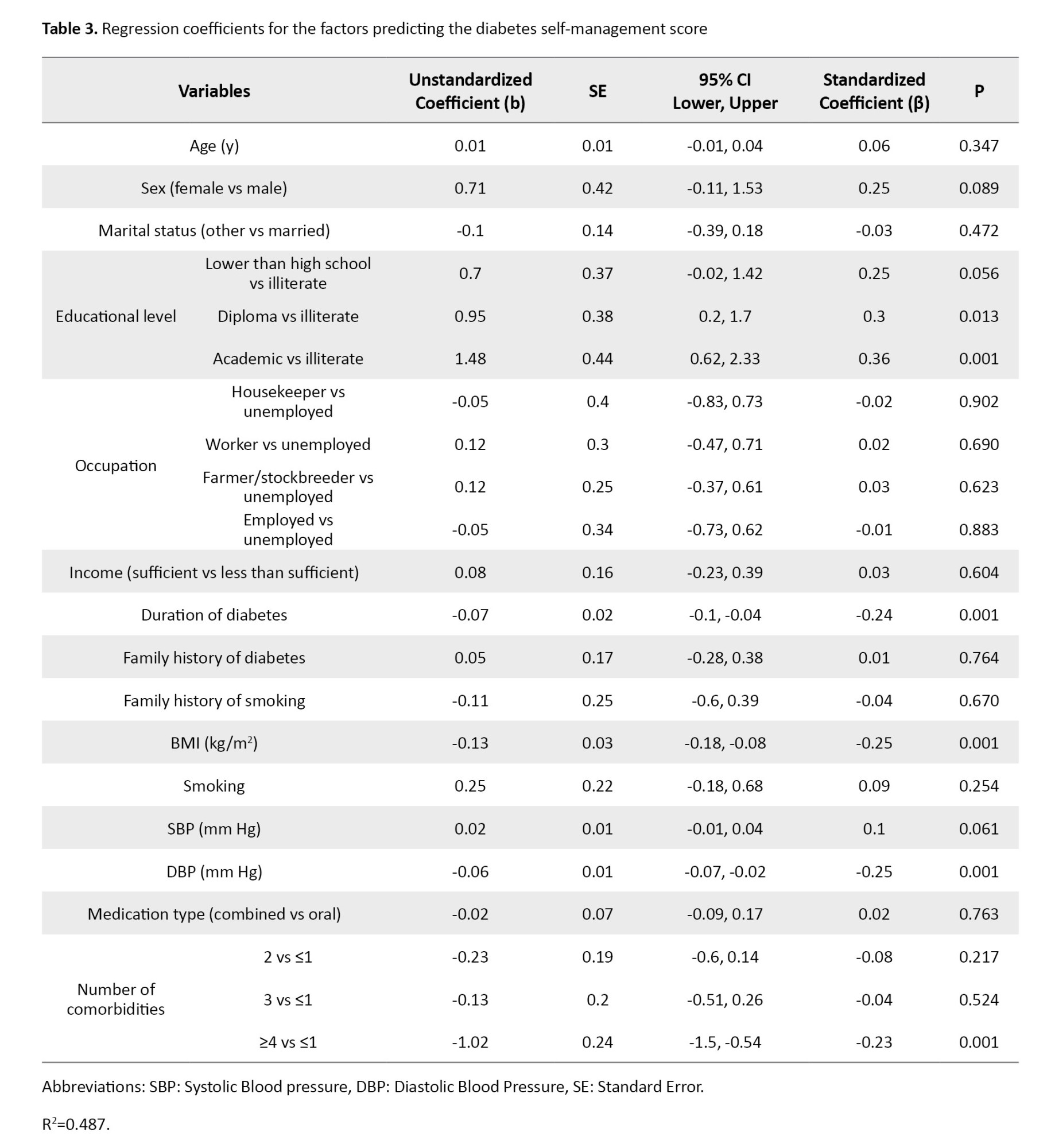

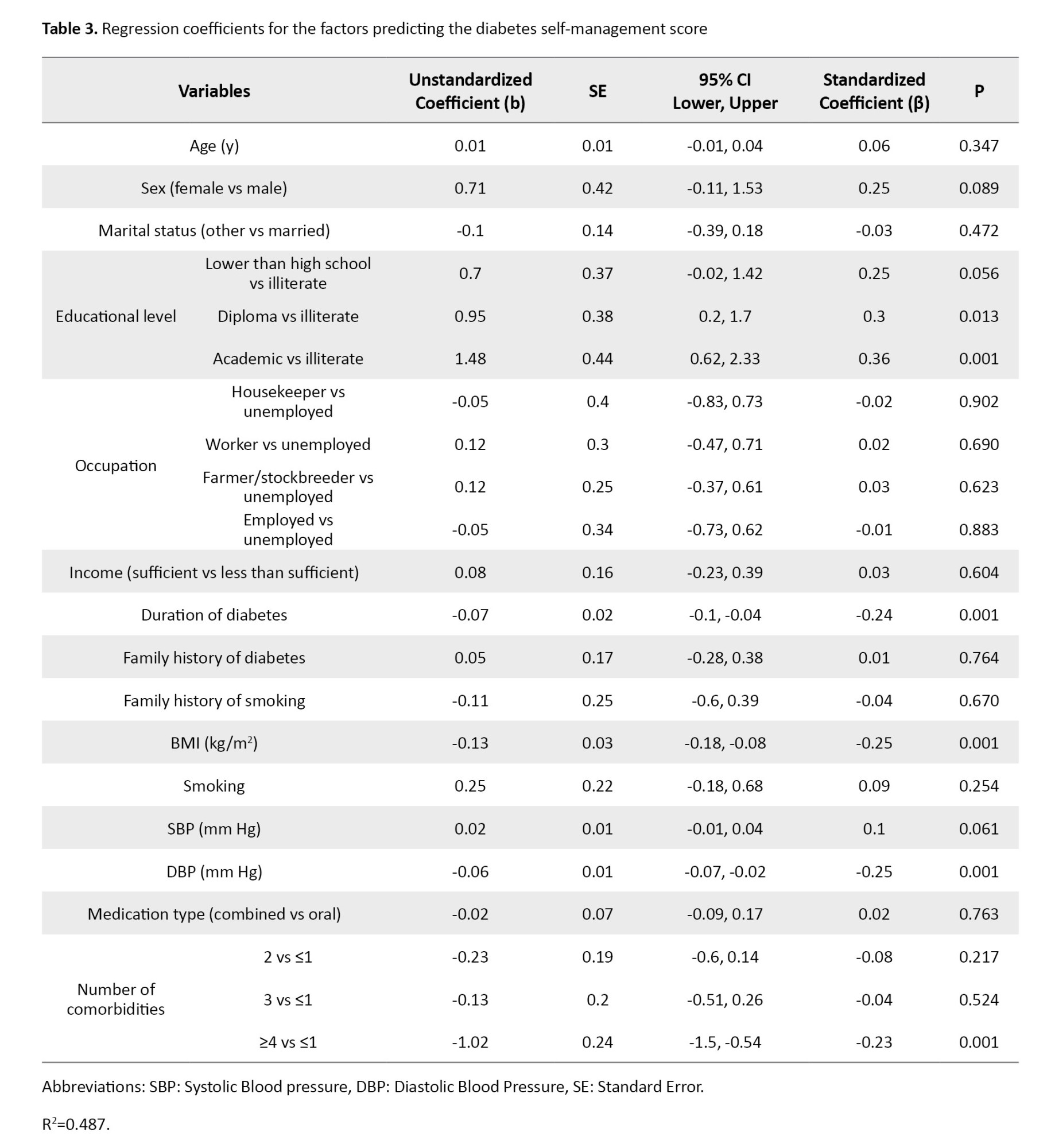

Multivariate analysis revealed that patients with high school education (b=0.95, 95% CI; 0.2%, 1.7%, P=0.013), and university education (b=1.48, 95% CI; 0.62%, 2.33%, P=0.001) had total DSMQ-R scores significantly higher than illiterate individuals by 0.95 and 1.48 units, respectively. However, longer duration of diabetes (b=-0.07, 95% CI; -0.1%, -0.04%, P=0.001) was significantly associated with decreased in DSMQ-R score; for every one-year increase in the disease duration, the score decreases significantly by 0.07 units. Patients with ≥4 comorbid conditions had significantly lower scores than those with only one comorbidity by 1.02 units (b=-1.02, 95% CI; -1.5%, -0.54%, P=0.001). For every one unit increase in BMI, the DSMQ-R score significantly decreases by 0.13 units (b=-0.13, 95% CI; -0.18%, -0.08%, P=0.001). The regression model showed that these factors explained 48.7% of the variance in total DSMQ-R score (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study revealed that most of the rural patients with T2D in Guilan Province had suboptimal self-management behaviors. This finding is consistent with the results of other studies [21-26], where the results indicated poor or inadequate levels of self-management behaviors in diabetic patients. Although different studies may have used different tools to examine self-management behavior and the levels of literacy and health literacy of their samples may have been different, the results of most studies are similar and indicate that patients are weak in self-management of their disease. Self-management education is essential for all diabetic patients. While traditional methods focused mainly on knowledge, modern approaches are patient-centered [27, 28]. For these modern programs to be effective, they should build self-efficacy, be culturally appropriate, and accommodate those with low health literacy [29]. Although appropriate, the NPPCD in Iran is so traditional and inadequately tailored to the specific needs of rural communities. Rural populations face distinct barriers, including marginalization, a shortage of specialists, logistical and transportation challenges, cultural differences, and low health literacy [30, 31].

In this study, physical activity had the lowest score among the self-management domains, consistent with the results of Jordan and Jordan [23]. A key challenge in rural areas is that daily farm labor is often mistaken for exercise. Therefore, rural patient education is needed to help them distinguish between them and promote the incorporation of exercises into daily routines. Effective interventions should offer specific, tailored guidance on the type, duration, intensity, and frequency of exercises, based on the patient’s capacity [32]. Family involvement and healthcare provider support are essential for sustaining this behavior change. Health literacy is also a key facilitator [33]. Blood glucose monitoring had the highest score among the self-management domains. Barriers such as the lack of monitoring devices and personal preferences may hinder its proper practice among some patients [34].

In this study, a higher educational level was significantly associated with higher self-management scores, although findings vary globally [35-38], and programs should be tailored for those with lower educational levels. Also, consistent with similar studies [39, 40], longer diabetes duration was significantly associated with a lower self-management score. In some studies, patients with longer diabetes duration showed greater self-care [41, 42], probably due to experiential learning or fear of complications. Higher BMI, combination therapy (insulin plus oral medications), and multiple comorbidities were also associated with poorer self-management in our study. Individuals with a higher BMI often struggle with physical activity and have unhealthy diet [35-38], and those on medication regimens face treatment burden, psychological stress, fear of hypoglycemia, and barriers to comply with self-management practices [43]; highlighting the need for enhanced education and emotional support.

This study had some limitations, including a small sample size, selection of samples from only rural areas in Guilan Province, and a cross-sectional design reliant on self-reported data, which may lead to response bias. Future research should use longitudinal designs and objective measures to confirm findings and better understand the dynamics of self-management behaviours.

In conclusion, despite over a decade of national self-management programs in Iran, this study found that self-management practices (particularly physical activity) of rural patients with T2D in Guilan Province are not favorable. Therefore, to improve the NPPCD in Iran, a tailored strategy for rural areas is needed, prioritizing patient activation, targeted education, and empowerment, and improving service accessibility and financial support, with continuous evidence-based monitoring. The interventions using the teach-back technique can be effective.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1401.572). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the study objectives to them.

Funding

This study was funded by Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Hojjat Houshyari Khah and Sajjad Pourbagheri; Data collection and interpretation: Sajjad Pourbagheri, Leilla Mirhadian, and Hojjat Houshyari Khah; Statistical analysis: Saman Maroufizadeh; Writing: Marzieh Shayesteh Fard; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, the staff of selected rural comprehensive health centers, and all participants for their support and cooperation in this research.

Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) is a chronic and progressively burdensome condition that can significantly affect patients and the health systems [1]. Statistics show that the prevalence of this disease in Iran is 4.11%, and approximately 4 million people are infected [2]. Guilan Province has shown the highest prevalence of T2D (18.9%) in Iran, with a prediabetes prevalence of 18.2% [3]. In Iran, the prevalence is notably higher in rural areas—approximately 17% more than in urban regions [4]. Globally, it is estimated that around 12% of total health expenditures are spent on treating T2D and its complications, with countries allocating between 5-20% of their national health budgets to combating this disease [5]. In Iran, the annual negative economic burden of diabetes has been estimated at over 3.78 billion USD [6, 7].

Effective diabetes management is achievable through self-care behaviours and ongoing self-management [4]. Diabetes self-management encompasses the ongoing, independent practices adopted by individuals with or at risk of diabetes to learn how to live with the disease, effectively manage their conditions, and control the potential complications [8]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) emphasizes that patients should actively participate in self-care [9]. It includes a healthy diet, physical activity, glucose monitoring, appropriate medication, problem-solving beliefs, adaptation skills, and risk-mitigation behaviours [8]. Given the lifelong nature of diabetes management, patient education and self-management support are essential components of diabetes care. To improve clinical outcomes and Quality of Life (QoL), various health systems, including Iran, have implemented comprehensive diabetes self-management programs [9]. Iran’s National Program for Prevention and Control of Diabetes (NPPCD) aligns with this self-management approach, focusing on early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, continuous care, and the prevention of complications [10-12]. This program aims to help patients maintain near-normal blood glucose levels and prevent disease-related complications [7, 13].

The findings of studies on the effectiveness of diabetes self-management programs in rural areas are contradictory. Some studies report inadequate self-care behaviours [7, 8, 13], some showed limited attempts to change unhealthy habits unless severe symptoms are present, and some demonstrated low engagement in overall self-care. Many rural patients fail to meet care objectives [12], underestimate disease severity, exhibit poor treatment adherence, and achieve target Haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in only about half of cases [7, 12]. Given the influence of cultural, social, and economic factors on self-management behaviours and the paucity of research on rural settings in Iran, the present study aimed to investigate the status of diabetes self-management and its associated factors among patients with T2D in rural areas of Guilan Province, north of Iran.

Materials and Methods

This analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in 2023 on 350 patients with T2D residing in rural areas of Guilan Province, Iran. Participants were selected using stratified, cluster, and convenience sampling methods from those enrolled in the NPPCD. Rural comprehensive health centers in Bandar Anzali, Guilan Province, were stratified into western and eastern centers as clusters. Then, 2–4 health centers were randomly selected from each cluster using a random number table. Finally, a convenience sample was used to select participants from the selected health centers. The study was conducted across three rural comprehensive health service centers and 16 affiliated health houses in the county. These centers provide regular care and diabetes education, led by trained community health workers, including periodic health assessments and laboratory tests. Inclusion criteria were age over 30 years, at least six months of diagnosed T2D, receiving training from the community health workers in accordance with NPPCD, regular performance of clinical lab tests including HbA1c and Fasting Blood Sugar (FBS) tests, at least two consecutive face-to-face visits to health houses for follow-up, informed consent, no mental or cognitive disorders, no visual or hearing impairments, no hospitalizations during the study due to diabetes complications, and no gestational diabetes, type 1 diabetes, cancer, or other disabling conditions requiring home care.

Data collection was performed by a structured questionnaire consisting of three sections: (A) a socio-economic/demographic form surveying age, sex, marital status, job, level of education, income, number of family members, diabetes duration, family history, and history of smoking; (B) a clinical profile form measuring anthropometric factors (height, weight, Body Mass Index [BMI]), physiological factors (blood pressure), and biochemical factors (FBS and HbA1c; HbA1c <7% indicating good glycaemic control, and ≥7% representing poor glycaemic control [14]); (C) The Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire - Revised (DSMQ-R), developed by Schmitt et al. [15-17]. We used its Persian version validated by Hosseinzadegan et al [18]. The DSMQ-R evaluates diabetes self-management practices in the past 8 weeks. It has two versions: A 20-item version for patients treated with oral antidiabetic medications and a 27-item version for those on insulin therapy. Both versions were used in this study. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (does not apply to me) to 3 (applies to me very much), assessing self-management in the following domains: Eating behavior, glucose monitoring, physical activity, and cooperation with the diabetes team. Scoring involved summing up the scores for each domain, and then transforming it to a scale range 1-10. Higher scores indicate more favorable self-management practices. In developing countries, 75% of participants score below the desired level of self-management. Consequently, in this study, scores ≥6 indicate favorable self-management, while scores <6 indicate unfavorable self-management [19, 20]. In our study, the reliability of the DSMQ-R was assessed among 30 participants. Cronbach’s α values were 0.844 for the 20-item version and 0.778 for the 27-item version, indicating acceptable internal consistency.

Data collection was carried out from March to June 2023. The researcher completed the socio-economic/demographic and DSMQ-R questionnaires via face-to-face interview. The clinical profile form was completed based on the patients’ registered health records. Statistical analysis was performed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Quantitative data were presented as Mean±SD and qualitative data as frequency (percentage). The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, graphical plots, and skewness and kurtosis indices. For univariate analyses, parametric tests (including independent t-test, one-way ANOVA, and Pearson’s correlation test) or their non-parametric equivalents (Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis, and Spearman’s correlation test) were applied. The multivariate analysis was conducted using multiple linear regression. All analyses were conducted in SPSS software, version 16. The statistically significant level was set at 0.05.

Results

In this study, the majority of participants were female (55.4%), housewives (50.3%), married (70.9%), with lower than high school education (54.9%), low income (74.9%), and with a family history of diabetes (79.7%) (Table 1).

The mean age of participants was 59±6.96 years; their mean BMI, 26.98±2.72 kg/m2; and their mean systolic blood pressure, 131.11±6.47 mm Hg. Most patients had 2-3 comorbid diseases.

The total mean DSMQ-R score was 5.23±1.42. There was a significant difference in the mean scores of the DSMQ-R domains based on the independent t-test results. The glucose monitoring domain had a score higher than that of other domains (5.99±1.57, P=0.001). The mean scores for eating behavior (5.28±2.05) and cooperation with the diabetes team (5.35±1.55) domains were significantly higher than that of the physical activity domain (3.87±2.06) (P=0.001). The total DSMQ-R score had a significant negative correlation with age (r=-0.23, P=0.001), diabetes duration (r=-0.44, P=0.001), BMI (r=-0.38, P=0.001), systolic blood pressure (r=-0.22, P=0.001), and diastolic blood pressure (r=-0.41, P=0.001) according to the Pearson correlation test results. According to independent t-test results, there were significant differences in total DSMQ-R score based on sex and type of medication (P=0.001), where the scores were higher in females than in males, and lower in those using insulin plus oral medications than in those using only oral medications (P=0.001). Significant differences in total DSMQ-R scores were also observed based on education level (P=0.001) and number of comorbidities (P=0.001), according to one-way ANOVA results. These results were shown in Table 2.

Multivariate analysis revealed that patients with high school education (b=0.95, 95% CI; 0.2%, 1.7%, P=0.013), and university education (b=1.48, 95% CI; 0.62%, 2.33%, P=0.001) had total DSMQ-R scores significantly higher than illiterate individuals by 0.95 and 1.48 units, respectively. However, longer duration of diabetes (b=-0.07, 95% CI; -0.1%, -0.04%, P=0.001) was significantly associated with decreased in DSMQ-R score; for every one-year increase in the disease duration, the score decreases significantly by 0.07 units. Patients with ≥4 comorbid conditions had significantly lower scores than those with only one comorbidity by 1.02 units (b=-1.02, 95% CI; -1.5%, -0.54%, P=0.001). For every one unit increase in BMI, the DSMQ-R score significantly decreases by 0.13 units (b=-0.13, 95% CI; -0.18%, -0.08%, P=0.001). The regression model showed that these factors explained 48.7% of the variance in total DSMQ-R score (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study revealed that most of the rural patients with T2D in Guilan Province had suboptimal self-management behaviors. This finding is consistent with the results of other studies [21-26], where the results indicated poor or inadequate levels of self-management behaviors in diabetic patients. Although different studies may have used different tools to examine self-management behavior and the levels of literacy and health literacy of their samples may have been different, the results of most studies are similar and indicate that patients are weak in self-management of their disease. Self-management education is essential for all diabetic patients. While traditional methods focused mainly on knowledge, modern approaches are patient-centered [27, 28]. For these modern programs to be effective, they should build self-efficacy, be culturally appropriate, and accommodate those with low health literacy [29]. Although appropriate, the NPPCD in Iran is so traditional and inadequately tailored to the specific needs of rural communities. Rural populations face distinct barriers, including marginalization, a shortage of specialists, logistical and transportation challenges, cultural differences, and low health literacy [30, 31].

In this study, physical activity had the lowest score among the self-management domains, consistent with the results of Jordan and Jordan [23]. A key challenge in rural areas is that daily farm labor is often mistaken for exercise. Therefore, rural patient education is needed to help them distinguish between them and promote the incorporation of exercises into daily routines. Effective interventions should offer specific, tailored guidance on the type, duration, intensity, and frequency of exercises, based on the patient’s capacity [32]. Family involvement and healthcare provider support are essential for sustaining this behavior change. Health literacy is also a key facilitator [33]. Blood glucose monitoring had the highest score among the self-management domains. Barriers such as the lack of monitoring devices and personal preferences may hinder its proper practice among some patients [34].

In this study, a higher educational level was significantly associated with higher self-management scores, although findings vary globally [35-38], and programs should be tailored for those with lower educational levels. Also, consistent with similar studies [39, 40], longer diabetes duration was significantly associated with a lower self-management score. In some studies, patients with longer diabetes duration showed greater self-care [41, 42], probably due to experiential learning or fear of complications. Higher BMI, combination therapy (insulin plus oral medications), and multiple comorbidities were also associated with poorer self-management in our study. Individuals with a higher BMI often struggle with physical activity and have unhealthy diet [35-38], and those on medication regimens face treatment burden, psychological stress, fear of hypoglycemia, and barriers to comply with self-management practices [43]; highlighting the need for enhanced education and emotional support.

This study had some limitations, including a small sample size, selection of samples from only rural areas in Guilan Province, and a cross-sectional design reliant on self-reported data, which may lead to response bias. Future research should use longitudinal designs and objective measures to confirm findings and better understand the dynamics of self-management behaviours.

In conclusion, despite over a decade of national self-management programs in Iran, this study found that self-management practices (particularly physical activity) of rural patients with T2D in Guilan Province are not favorable. Therefore, to improve the NPPCD in Iran, a tailored strategy for rural areas is needed, prioritizing patient activation, targeted education, and empowerment, and improving service accessibility and financial support, with continuous evidence-based monitoring. The interventions using the teach-back technique can be effective.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1401.572). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the study objectives to them.

Funding

This study was funded by Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Hojjat Houshyari Khah and Sajjad Pourbagheri; Data collection and interpretation: Sajjad Pourbagheri, Leilla Mirhadian, and Hojjat Houshyari Khah; Statistical analysis: Saman Maroufizadeh; Writing: Marzieh Shayesteh Fard; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, the staff of selected rural comprehensive health centers, and all participants for their support and cooperation in this research.

References

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas, Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2015. [Link]

- Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. Role of self-care in management of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2013; 12(1):14. [DOI:10.1186/2251-6581-12-14] [PMID]

- Khamseh ME, Sepanlou SG, Hashemi-Madani N, Joukar F, Mehrparvar AH, Faramarzi E, et al. Nationwide prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes and associated risk factors among Iranian adults: Analysis of data from PERSIAN cohort study. Diabetes Ther. 2021; 12(11):2921-38. [DOI:10.1007/s13300-021-01152-5]

- Pullyblank K, Scribani M, Wyckoff L, Krupa N, Flynn J, Henderson C, et al. Evaluating the Implementation of the diabetes self-management program in a rural population. Diabetes Spectr. 2022; 35(1):95-101. [DOI:10.2337/ds21-0002] [PMID]

- Abou Hashish EA, Alnajjar H. Digital proficiency: Assessing knowledge, attitudes, and skills in digital transformation, health literacy, and artificial intelligence among university nursing students. BMC Med Educ. 2024; 24(1):508. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-024-05482-3] [PMID]

- Mirzaei M, Rahmaninan M, Mirzaei M, Nadjarzadeh A, Dehghani Tafti AA. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus, pre-diabetes, undiagnosed and uncontrolled diabetes in Central Iran: Results from Yazd health study. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):166. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-8267-y] [PMID]

- Khazaei S, Saatchi O, Mirmoeini R, Bathaei SJ. [Assessing treatment and care in patients with type 2 diabetes in rural regions of Hamadan Province in 2013 (Persian)]. Avicenna J Clin Med. 2015; 21(4):310-8. [Link]

- Scalzo P. From the association of diabetes care & education specialists: The role of the diabetes care and education specialist as a champion of technology integration. Sci Diabetes Self Manag Care. 2021; 47(2):120-3. [DOI:10.1177/0145721721995478] [PMID]

- Hulst SJ. Diabetes self-management education service at a rural Minnesota health clinic [PhD Thesis]. Fargo: North Dakota State Universityof Agriculture and Applied Science; 2019. [Link]

- Alirezaei Shahraki R,. Aliakbari Kamrani A, Sahaf R, Abolfathi Momtaz Y. [Effects of nationwide program for prevention and control of diabetes initiated by the ministry of health on elderly diabetic patients’ knowledge, attitude and practice in Isfahan (Persian)]. Salmand Iran J Ageing. 2019; 14(1):84-95. [DOI:10.32598/SIJA.14.1.84]

- Harrington C, Carter-Templeton HD, Appel SJ. Diabetes self-management education and self-efficacy among African American women living with type 2 diabetes in rural primary care. J Dr Nurs Pract. 2017; 10(1):11-16. [DOI:10.1891/2380-9418.10.1.11] [PMID]

- Solares D. Effect of diabetic self-management education using short message technology [PhD Thesis]. Phoenix: Grand Canyon University; 2021. [Link]

- Cole JB, Florez JC. Genetics of diabetes mellitus and diabetes complications. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020; 16(7):377-90. [DOI:10.1038/s41581-020-0278-5] [PMID]

- Alavi Nia SM, Ghotbi M, Mahdavi Hazaveh A, Jamshidi Kermanchi, A, Noslli Esfahani E, Yarahmadi, Sh. [National program for prevention and control of type 2 diabetes [Persian]. Tehran: Tehran Sepehr Barg Publications; 2012. [Link]

- Schmitt A, Gahr A, Hermanns N, Kulzer B, Huber J, Haak T. The diabetes self-management questionnaire (DSMQ): development and evaluation of an instrument to assess diabetes self-care activities associated with glycaemic control. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013; 11:138. [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-11-138] [PMID]

- Schmit Ag. Diabetes self-management questionnaire (DSMQ) user information and scoring guide [Internet]2012. [Updated 2025 December 30]. Available from: [Link]

- Márkus B, Hargittay C, Iller B, Rinfel J, Bencsik P, Oláh I, et al. Validation of the revised diabetes self-management questionnaire (DSMQ-R) in the primary care setting. BMC Prim. Care. 2022; 23(1):2. [DOI:10.1186/s12875-021-01615-5]

- Hosseinzadegan F, Azimzadeh R, Parizad N, Esmaeili R, Alinejad V, Hemmati Maslakpak M. Psycometric evaluation of the diabetes self-management questionnaire- revised form (DSMQ-R) in patients with diabetes. Nurs Midwifery J. 2021; 19(2):109-18. [Link]

- Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, Duker P, Funnell MM, Fischl AH, et al. Diabetes self-management education and support in type 2 diabetes: A joint position statement of the American Diabetes Association, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Diabetes Educ. 2017; 43(1):40-53. [DOI:10.1177/0145721716689694]

- Mandpe A, Pandit V, Dawane J, Patel H. Correlation of disease knowledge with adherence to drug therapy, blood sugar levels and complications associated with disease among type 2 diabetic patients. J Diabetes Metab. 2023; 5(5):369. [Link]

- Luo H, Bell RA, Winterbauer NL, Xu L, Zeng X, Wu Q, et al. Trends and rural-urban differences in participation in diabetes self-management education among adults in North Carolina: 2012-2017. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022; 28(1):E178-e84. [DOI:10.1097/PHH.0000000000001226]

- Sarabi RE, Mokhtari Z, Tahami AN, Borhaninejad VR, Valinejadi A. Assessment of type 2 diabetes patients’ self-care status learned based on the national diabetes control and prevention program in health centers of a selected city, Iran. Koomesh. 2021; 23(4):465-73.[Link]

- Jordan DN, Jordan JL. Self-care behaviors of Filipino-American adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2010; 24(4):250-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2009.03.006] [PMID]

- Doroodgar M, Doroodgar M, Tofangchiha S. Evaluation of relation between hba1c level with cognitive disorders and depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019; 7(15):2462-6. [DOI:10.3889/oamjms.2019.658] [PMID]

- Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Talaei B, Jalali BA, Najarzadeh A, Mozayan MR. The effect of ginger powder supplementation on insulin resistance and glycemic indices in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2014; 22(1):9-16. [DOI:10.1016/j.ctim.2013.12.017] [PMID]

- Moradi G, Shokri A, Mohamadi-Bolbanabad A, Zareie B, Piroozi B. Evaluating the quality of care for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus based on the HbA1c: A national survey in Iran. Heliyon. 2021; 7(3):e06485. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06485]

- Matteo Ciccone M, Scicchitano P, Cameli M, Cecere A, Mattioli AV. Endothelial function in pre-diabetes, diabetes and diabetic cardiomyopathy: A review. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolism. 2014; 5:1-10. [Link]

- Mahfouz EM, Awadalla HI. Compliance to diabetes self-management in rural El-Mina, Egypt. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2011; 19(1):35-41. [DOI:10.21101/cejph.a3573] [PMID]

- Katsarou A, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Rawshani A, Dabelea D, Bonifacio E, Anderson BJ, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017; 3:17016. [PMID]

- Freeman K, Hanlon M, Denslow S, Hooper V. Patient engagement in type 2 diabetes: A collaborative community health initiative. Diabetes Educ. 2018; 44(4):395-404. [DOI:10.1177/0145721718784262] [PMID]

- Halepian L, Saleh MB, Hallit S, Khabbaz LR. Adherence to insulin, emotional distress, and trust in physician among patients with diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Diabetes Therapy. 2018; 9(2):713-26. [DOI:10.1007/s13300-018-0389-1]

- Ranasinghe P, Pigera AS, Ishara MH, Jayasekara LM, Jayawardena R, Katulanda P. Knowledge and perceptions about diet and physical activity among Sri Lankan adults with diabetes mellitus: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2015; 15(1):1160. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-015-2518-3] [PMID]

- Yamashita T, Bailer AJ, Noe DA. Identifying at-risk subpopulations of canadians with limited health literacy. Epidemiol Res Int. 2013; 2013(1):130263.

- Lycett HJ, Raebel EM, Wildman EK, Guitart J, Kenny T, Sherlock JP, et al. Theory-based digital interventions to improve asthma self-management outcomes: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2018; 20(12):e293. [DOI:10.2196/jmir.9666] [PMID]

- Lambrinou E, Hansen TB, Beulens JW. Lifestyle factors, self-management and patient empowerment in diabetes care. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019; 26(2_suppl):55-63. DOI:10.1177/2047487319885455] [PMID]

- Almomani MH, Al-Tawalbeh S. Glycemic control and its relationship with diabetes self-care behaviors among patients with type 2 diabetes in Northern Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022; 16:449-65. [DOI:10.2147/PPA.S343214] [PMID]

- Dit L, Baban A, Dumitrascu DL. Diabetes’s adherence to treatment: The predictive value of satisfaction with medical care. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012; 33:508-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.173]

- Arrelias CCA, Faria HTG, Teixeira CRdS, Santos MAd, Zanetti ML. Adherence to diabetes mellitus treatment and sociodemographic, clinical and metabolic control variables. Acta Paul Enfermagem. 2015; 28(4):315-22. [DOI:10.1590/1982-0194201500054]

- Ahmad Sharoni SK, Shdaifat EA, Mohd Abd Majid HA, Shohor NA, Ahmad F, Zakaria Z. Social support and self-care activities among the elderly patients with diabetes in Kelantan. Malays Fam Physician. 2015; 10(1):34-43. [PMID]

- Al-Qahtani AM. Frequency and factors associated with inadequate self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Najran, Saudi Arabia: Based on diabetes self-management questionnaire. Saudi Med J. 2020; 41(9):955. [DOI:10.15537/smj.2020.9.25339]

- Abou-Gamel M, Al-Moghamsi E, Jabri G, Alsharif A, Al-Rehaili R, Al-Gabban A, et al. Level of glycemic control and barriers of good compliance among diabetic patients in Al-Madina, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Adv Med Med Res. 2014; 5(6):819-30. [DOI:10.9734/BJMMR/2015/11917]

- Jackson IL, Adibe MO, Okonta MJ, Ukwe CV. Knowledge of self-care among type 2 diabetes patients in two states of Nigeria. Pharm Pract. 2014; 12(3):404. [DOI:10.4321/S1886-36552014000300001]

- Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B, Cryer P, Dagogo-Jack S, Fish L, et al. Hypoglycemia and diabetes: A report of a workgroup of the American diabetes association and the endocrine society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 98(5):1845-59. [DOI:10.1210/jc.2012-4127] [PMID]

Article Type : Applicable |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2025/09/1 | Accepted: 2025/11/5 | Published: 2026/01/11

Received: 2025/09/1 | Accepted: 2025/11/5 | Published: 2026/01/11

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |