Wed, Jan 28, 2026

Volume 36, Issue 1 (1-2026)

JHNM 2026, 36(1): 54-62 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

yadegari M A, Emami-Sigaroudi A, Jamshidi M, masaebi F, shirvani Y. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Team Performance, Outcomes, and Associated Factors in Iran. JHNM 2026; 36 (1) :54-62

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2564-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2564-en.html

Mohammad Ali Yadegari1

, Abdolhossein Emami-Sigaroudi2

, Abdolhossein Emami-Sigaroudi2

, Mohammadreza Jamshidi3

, Mohammadreza Jamshidi3

, Fatemeh Masaebi4

, Fatemeh Masaebi4

, Yadolah Shirvani *5

, Yadolah Shirvani *5

, Abdolhossein Emami-Sigaroudi2

, Abdolhossein Emami-Sigaroudi2

, Mohammadreza Jamshidi3

, Mohammadreza Jamshidi3

, Fatemeh Masaebi4

, Fatemeh Masaebi4

, Yadolah Shirvani *5

, Yadolah Shirvani *5

1- Assistant Professor, Department of Operating Room, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran.

2- Professor, Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Health and Metabolic Diseases Research Institute, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran.

5- PhD Candidate, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,yadolah.shirvani@gmail.com

2- Professor, Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Health and Metabolic Diseases Research Institute, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran.

5- PhD Candidate, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 565 kb]

(47 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (102 Views)

References

Full-Text: (4 Views)

Introduction

Cardiac Arrest (CA) is a leading cause of death worldwide. It refers to the sudden cessation of systemic blood circulation and spontaneous breathing. It usually occurs without significant warning signs [1-3] and is accompanied by a cardiac dysrhythmia. The mean age of individuals with CA is around 65 years, with at least 40% under 65 years of age [4]. Each year, 350000–450000 individuals in the United States and 700000 in Europe experience CA [5, 6]. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) is the most important measure for CA management, and its outcomes depend on the timely performance of basic and advanced life support measures [7], CPR duration, underlying disease, the timely use of a cardiac defibrillator, and the CPR team members’ knowledge and skillfulness [8]. Despite continuous revisions and improvements of CPR guidelines, only 6–9% of patients survive after CPR [9]. The CPR success rate in Iran for in-hospital CA varies from 2% to 27% across different studies [10-12]. CPR is a team-based measure, and its quality and success rely not only on team members’ technical skills, but also on their non-technical skills [13] such as coordination, collaboration, communication, leadership, and teamwork [14] that allow team members to effectively work together and attain their common goals [15]. It is a determining factor of emergency condition management, and its ineffectiveness may negatively affect patient and public safety [16, 17].

The leader of the CPR team is usually a competent physician who determines the CPR plan [18]. According to the European Resuscitation Council (ERC), team structure, dynamics, and leadership significantly influence the performance of the interdisciplinary healthcare team during resuscitation [19]. Poor teamwork during CPR endangers patient safety, negatively affects CPR outcomes [20, 21], and may lead to lifelong disabilities or death in patients [22]. Several factors can affect the CPR team’s performance, including culture, resources, education, guidelines, and team communication [23-25]. Although CPR guidelines emphasize non-technical skills, they lack strategies for improving teamwork, leadership, and communication [24]. Some studies reported that 70–80% of medical errors are due to poor communication and teamwork [25, 26]. Moreover, the conditions of patients and their companions, as well as intra- and extra-organizational factors, can affect teamwork [27]. Other effective factors include CPR onset delay, members’ limited experience and skills, equipment shortages, environmental conditions, patients’ conditions, and family actions [28].

To the best of our knowledge, there is scant research that has evaluated the performance of the in-hospital CPR team in Iran. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the performance of the CPR team in teaching hospitals of Zanjan, Iran, and find its influential factors.

Materials and Methods

This observational descriptive-analytical study was conducted from June 2024 to February 2025 in two teaching hospitals affiliated with Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran. There were CPR teams working for 24 hours in these two hospitals with a predetermined monthly schedule and CPR announcement equipment. The team leaders were clinically competent, either physicians or specialty residents (e.g. emergency medicine, cardiology, anesthesiology, or internal medicine). The study population consisted of all CPR events performed in the hospitals. Using a census sampling method, all eligible CPR events during the study period were included. The sample size was determined to be at least 50 CPRs, based on a previous study reporting a Standard Deviation (SD) of 3.6 for teamwork scores, and considering a 5% significance level and a precision of 1 [29]. Inclusion criteria were CPRs for patients >18 years, CPR team size >3, and CPR duration >5 minutes. Incomplete documentation of CPR measures (the cases where the assessor could not determine the exact time and method of initiation because they were not present for direct observation from the very beginning) was the exclusion criterion.

The data collection instrument was the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM), supplemented by a demographic form designed to record relevant information of both patients and CPR team members. The TEAM was developed by Cooper et al. for the assessment of teamwork in emergency conditions [30]. It has 11 items measuring three non-technical teamwork skills, including leadership (n=2), teamwork (n=7), and task management (n=2), and one item measuring global teamwork performance. The items are rated on a scale from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“almost always”). The total score of the instrument ranges from 0 to 44. Scores ≤33, 34–39, and 40–44 indicate poor, good, and excellent team performance, respectively. The total score of the global teamwork performance rating is 0–10; scores <7 and 9–10 indicate poor and excellent global performance, respectively [31]. Previous studies have confirmed the psychometric properties of the TEAM [32-34]. In our study, it was first translated into Persian and culturally adapted using a standard forward–backward method by two bilingual experts. Face and content validity were then evaluated by a panel of experts (n=10), including specialists in emergency medicine and cardiology. Both the Scale-Content Validity Index (S-CVI) and the average of Item-Content Validity Indices (S-CVI/Ave) were 0.92. Reliability was assessed in a pilot study on 10 CPR events. Two independent raters scored each event simultaneously. Inter-rater reliability was 0.87, indicating strong agreement, and internal consistency, measured by Cronbach’s α, was 0.90.

For data collection, an independent rater visited the wards where CPRs were conducted during different work shifts. To minimize observer bias, the rater was introduced to the CPR team as a helping assistant to the supervisor, concealing their primary role as a research assessor. The rater observed eligible CPRs and completed the TEAM questionnaire immediately after each CPR concluded, ensuring the team remained unaware of the formal evaluation. SPSS software, version 27 was employed for data analysis. Categorical variables were described using frequency and percentage measures, and numerical variables were described using Mean±SD, median, and interquartile range. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test revealed that some variables did not follow a normal distribution (P<0.05). Therefore, non-parametric methods, including Spearman’s correlation test and Mann-Whitney U test, were used for data analysis.

Results

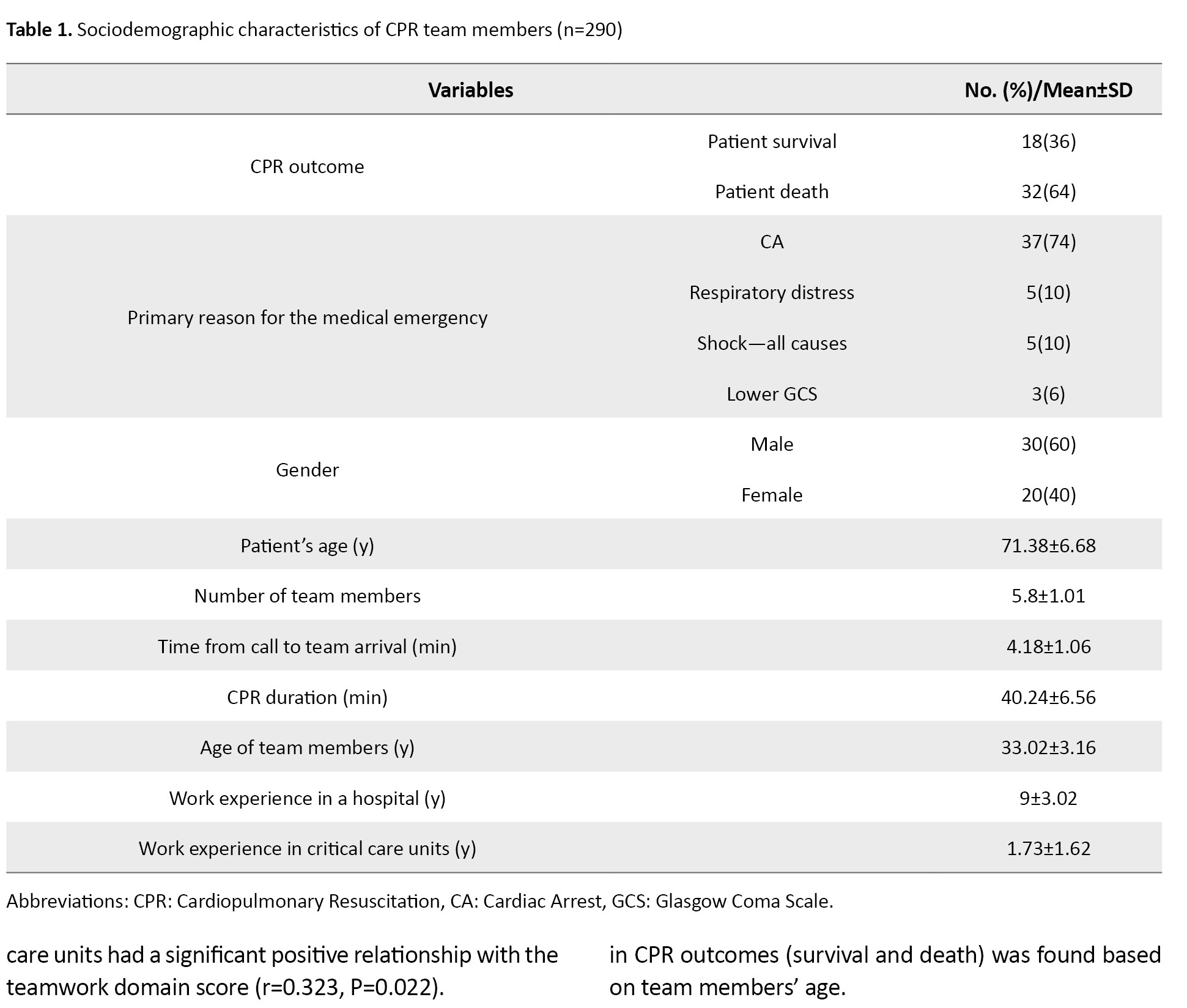

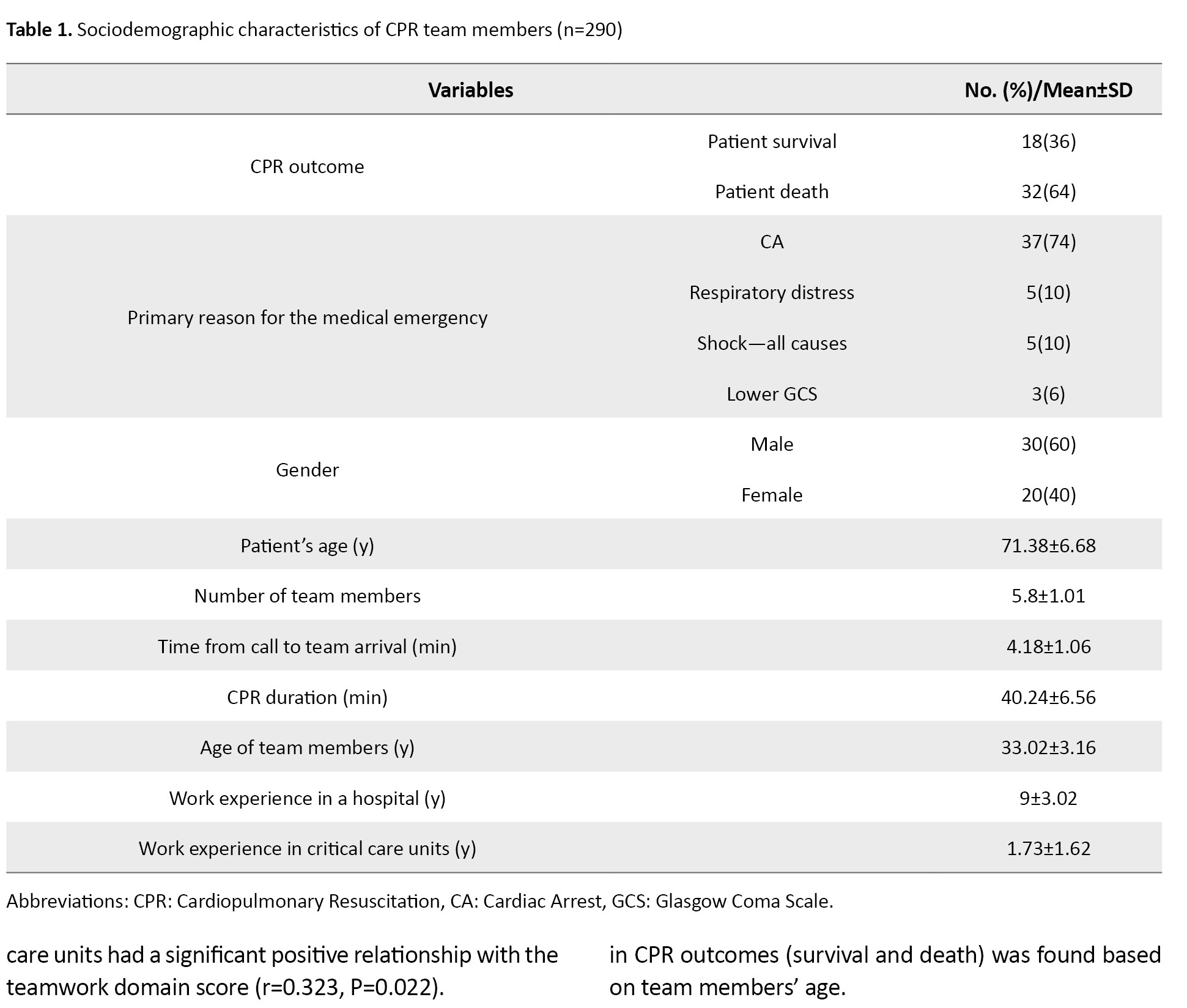

This study evaluated the non-technical skills of 290 CPR team members across 50 in-hospital CA events. The resuscitated patients were aged 57–82 years with a mean age of 71.38±6.68 years. Most patients were male (60%), and the most common leading cause of CPR was cardiac disease (74%). Their other characteristics are presented in Table 1.

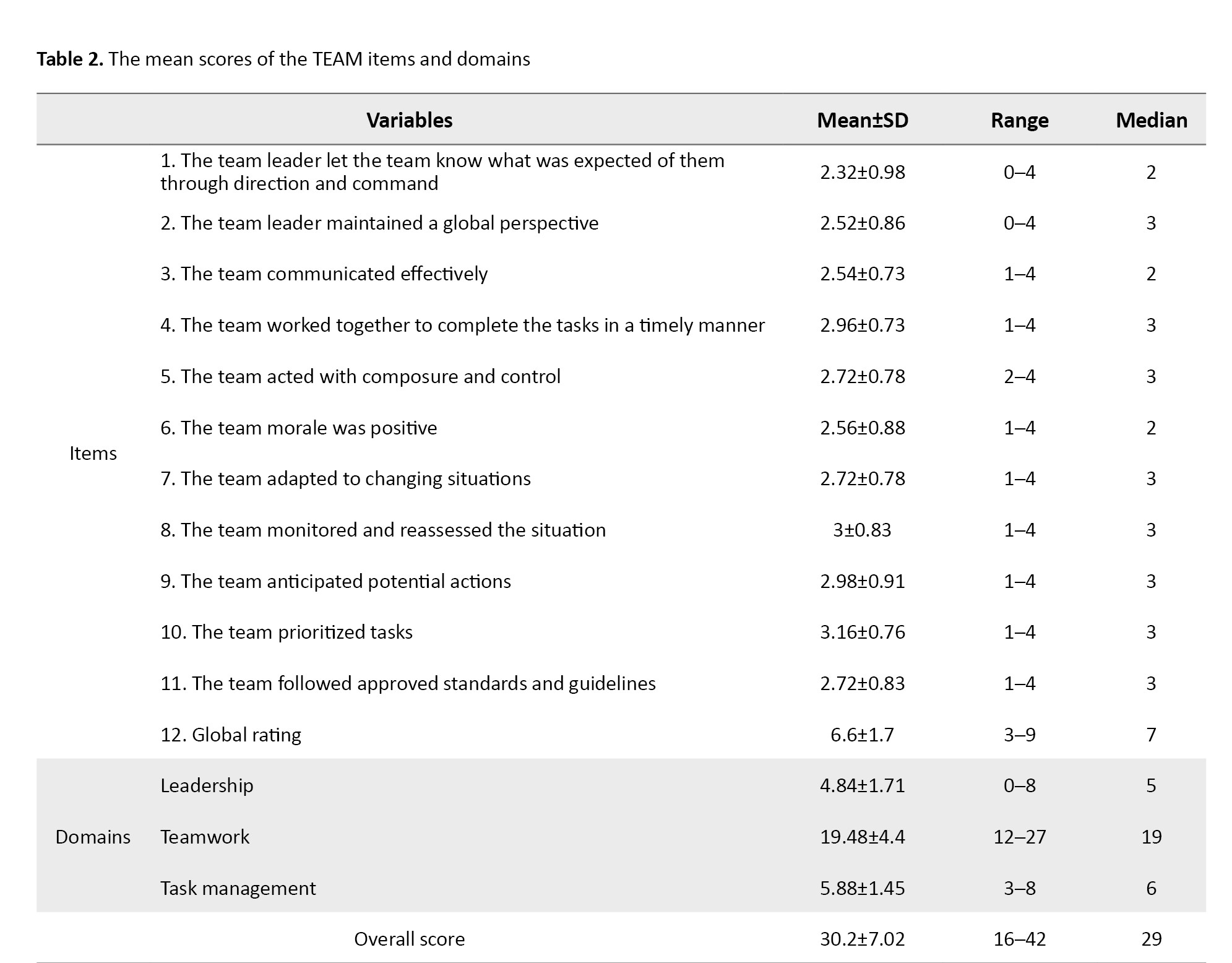

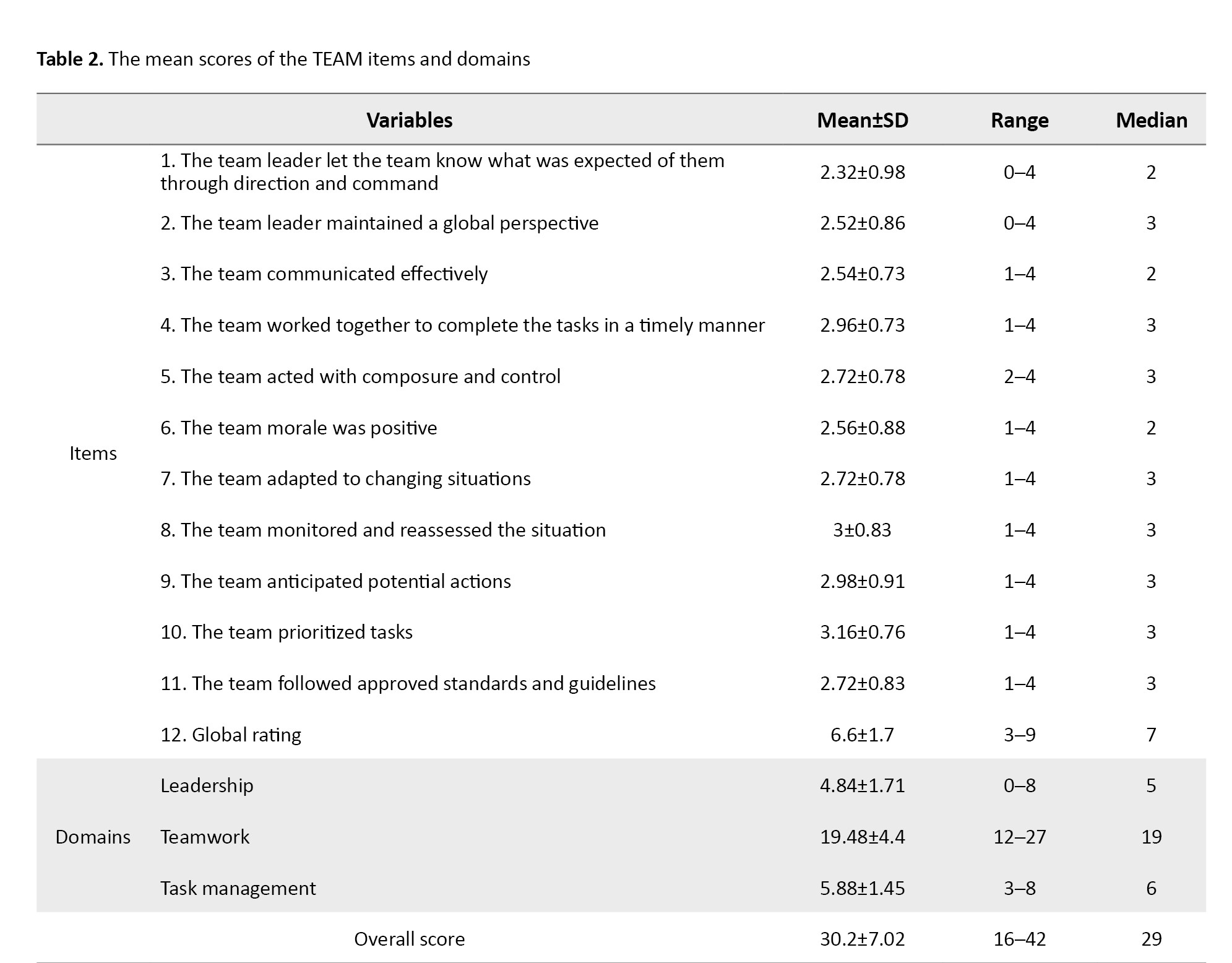

The total TEAM score of the CPR team was 30.2±7.02. The domain with the highest mean score was task management (5.88±1.45), while the lowest was leadership (4.84±1.71). The mean teamwork score was 19.48±4.4. Among the items, the lowest mean score was for item No.1 (2.32±0.98) and the highest mean score was for item No.10 (3.16±0.76) (Table 2).

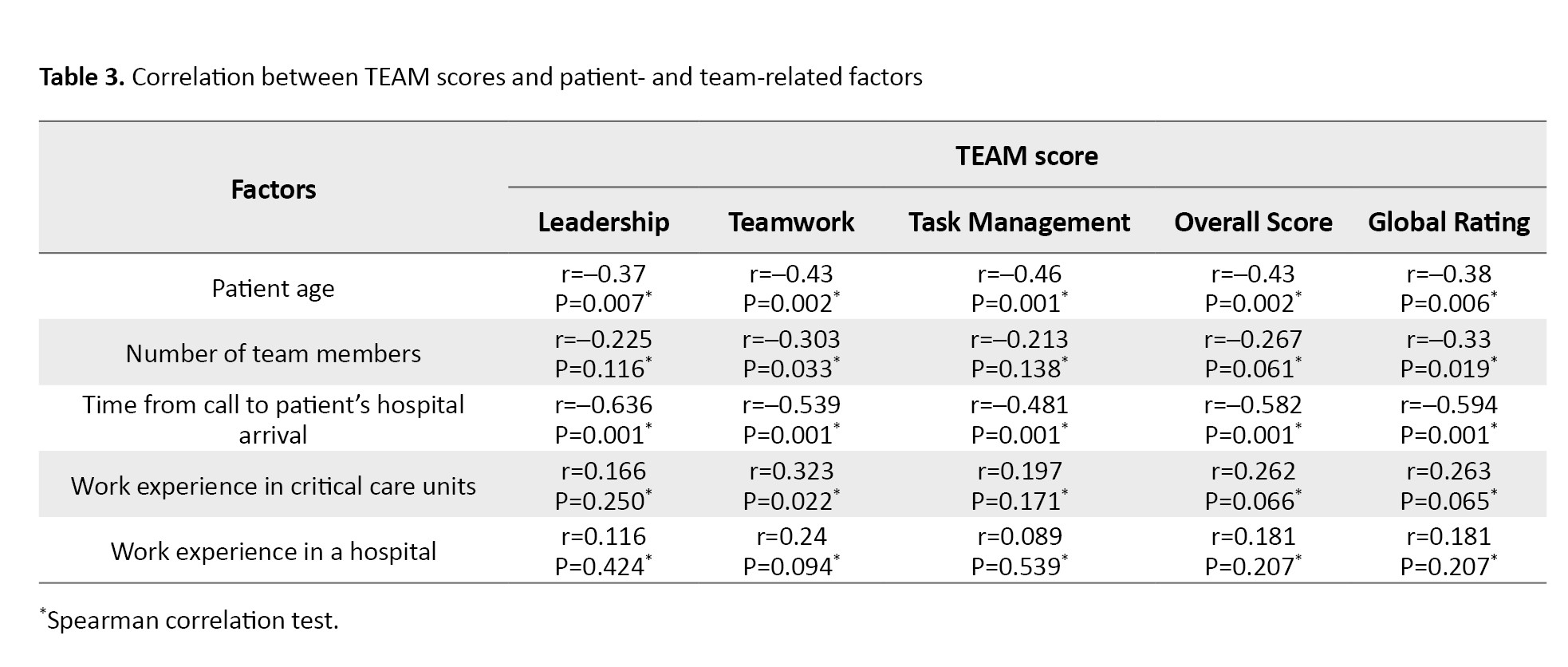

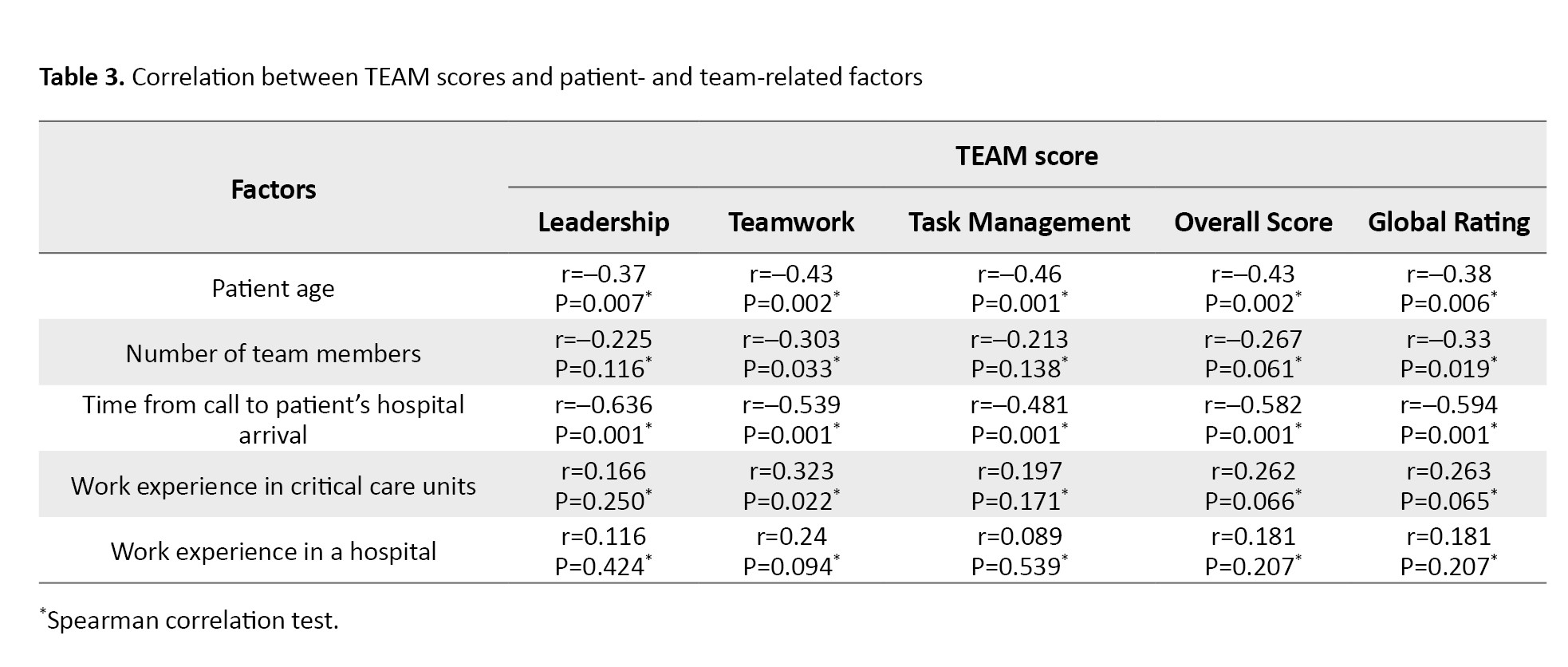

As shown in Table 3, the total TEAM score had a significant negative relationship with patient age (r=–0.43, P=0.002), denoting poorer team performance for elderly patients.

Moreover, the teamwork domain of TEAM showed a significant negative relationship with the number of team members (r=–0.303, P=0.033), suggesting poorer performance by larger CPR teams. The call-to-arrival interval also had a significant negative relationship with the total TEAM score (r=–0.582, P=0.001), indicating that longer intervals were associated with poorer CPR team performance. On the other hand, CPR team members’ work experience in critical care units had a significant positive relationship with the teamwork domain score (r=0.323, P=0.022).

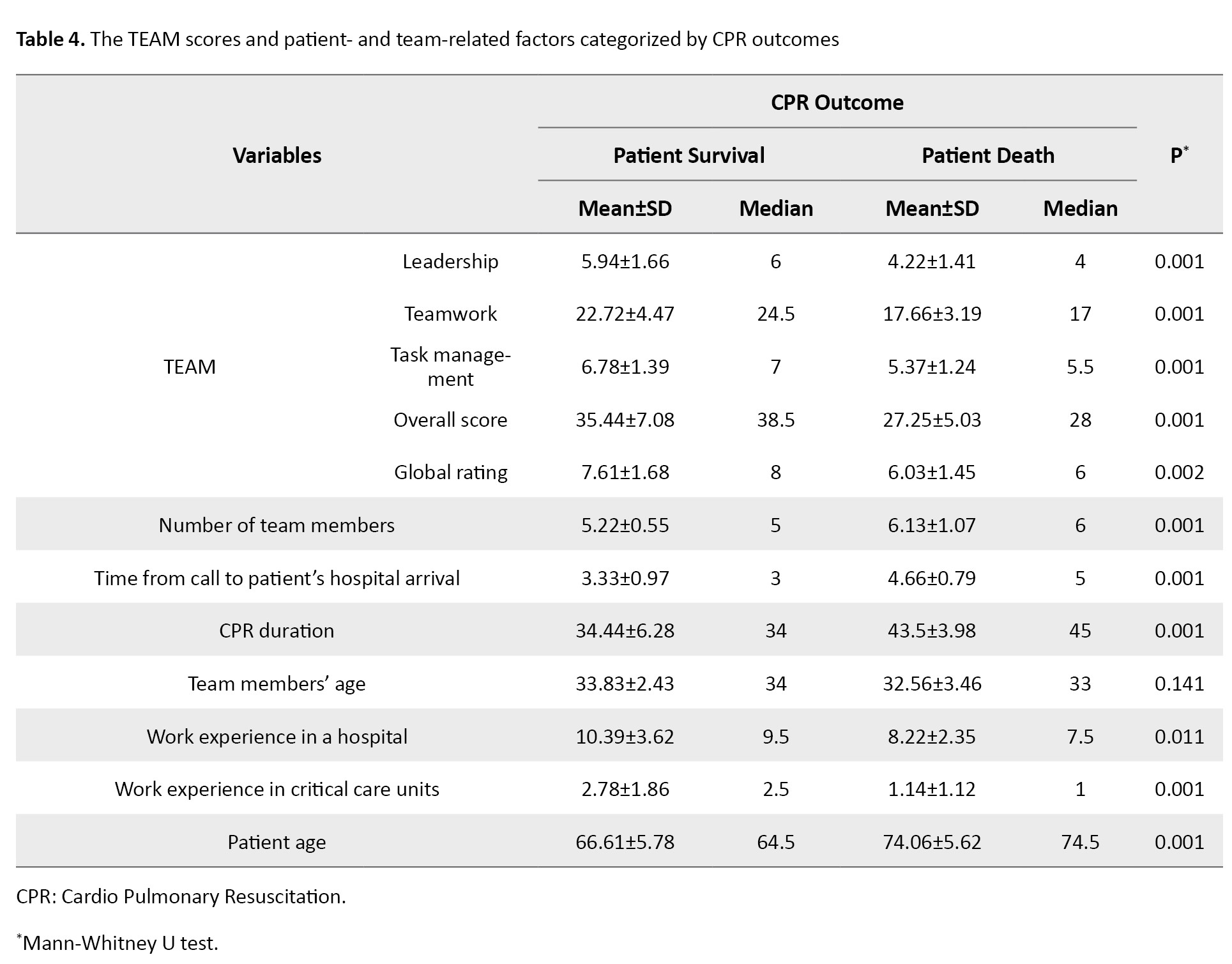

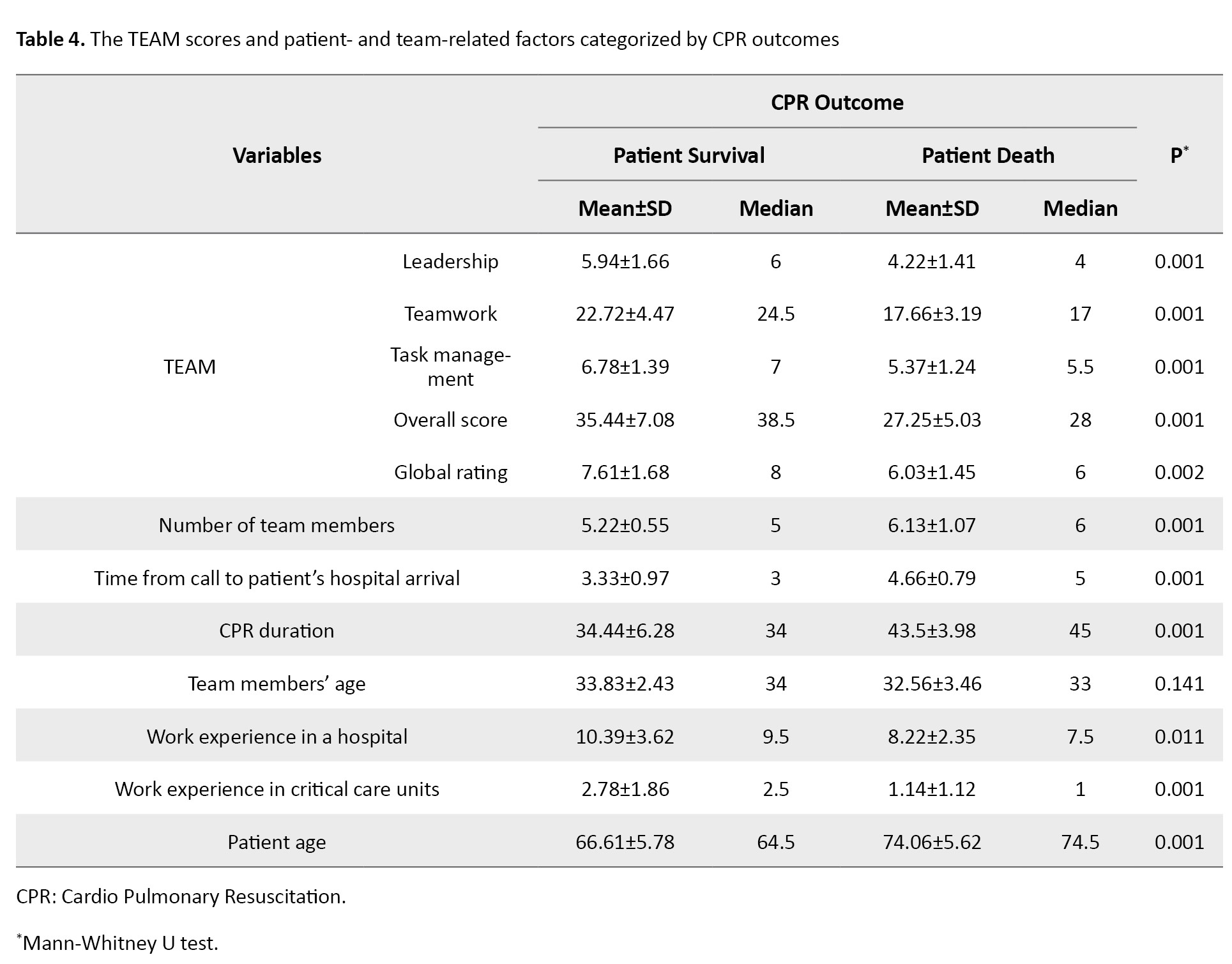

According to the Mann–Whitney U test results (Table 4), the TEAM score was significantly different based on CPR outcomes (patient survival/death).

Those with patient survival outcome had significantly higher scores in leadership (P=0.001), teamwork (P=0.001), task management (P=0.001), overall performance (P=0.001), and global rating (P=0.002), indicating that better team performance was related to more favorable CPR outcomes. Furthermore, clinicians who contributed to patient survival had significantly more extensive work experience, both in critical care units (P=0.001) and in hospitals (P=0.011). This indicates that greater clinical experience may be a critical factor contributing to effective team performance and, consequently, successful CPR. In contrast, for the CPR events with patient death outcome, there was a larger team size (P=0.001), longer call-to-arrival interval (P=0.001), longer CPR durations (P=0.001), and older patients (P=0.001). These findings imply that delays in response, extended resuscitation, larger team sizes, and high patient age may be negatively associated with CPR success. No statistically significant difference in CPR outcomes (survival and death) was found based on team members’ age.

Discussion

This study evaluated the performance of the CPR team in teaching hospitals of Zanjan, the CPR outcomes, and influential factors for 50 in-hospital CPRs. The lowest performance score was found in the leadership domain, underscoring significant challenges in CPR team leadership, particularly in the absence of a designated team leader. CPR leadership is one of the most important factors in efficient CPR team performance [35]; CPR teams with better leadership deliver higher-quality CPR and faster defibrillation [15]. The American Heart Association (AHA) and the ERC recommend incorporating teamwork and leadership education into educational programs on advanced life support and resuscitation [36, 37]. For the item “the team prioritized tasks”, the highest score was reported. The AHA guideline also emphasizes the importance of teamwork and task prioritization [36].

Study findings revealed that a larger CPR team size was associated with poorer non-technical skills. Therefore, it seems that large CPR team size negatively affects team performance, leadership, and communication. This may be due to the poorer communication clarity and poorer team coordination in larger CPR teams. The AHA recommends that CPR teams should include at least two members, while larger teams consisting of 3-5 members may have better performance [38]. In agreement with our findings, a study reported a significant negative relationship between CPR team size and CPR team performance, indicating that larger teams have poorer team performance [31]. Moreover, we found a significant negative relationship between CPR team size and patient survival, suggesting that larger teams are associated with lower patient survival. Coordination and collaboration among members are probably more difficult in larger teams; medium-sized teams consisting of 3-5 members may produce the best outcomes.

An inverse relationship was also observed between patient age and CPR team performance, suggesting that teams may perform less effectively when resuscitating older patients. This finding is consistent with those of previous reports [37, 39]. The lower survival rates among older adults likely reflect the greater burden of comorbid conditions in this population [40, 41]. There was a significant negative relationship between CPR team performance and the time from call to patient arrival. The recorded time in our study generally fell within the critical golden period for initiating CPR following CA. Maintaining intervention within this crucial window is vital for preserving neurological function and preventing irreversible damage to vital organs. Timely CPR onset and defibrillation are important to reduce the rates of post-CA complications and death. This is supported by evidence indicating a marked decline in survival likelihood with progressively delayed resuscitation efforts [21]. Nurses’ long delays in starting CPR and using a defibrillator may indicate that they, as the first responders to CA, may fail to transform their knowledge and skills into timely and effective measures. In our study, the call–hospital arrival interval also had a significant relationship with survival rate, denoting that a shorter interval was associated with greater CPR success. Similarly, a previous study reported that call–arrival time had a significant effect on CPR success [42]. It seems that the timely arrival of CPR team members is associated with greater coherence, coordination, motivation, and self-confidence, thereby increasing the CPR success rate.

The findings demonstrated that CPR team performance was higher among team members with greater work experience in critical care units. The CPR team members’ knowledge and skills can affect CPR outcomes [43]. A study found that the survival rate after CPR performed by CPR specialists was higher than that performed by non-specialized staff [44]. Another study demonstrated that implementation of CPR by specialized skilled teams significantly improved patient survival rates [45]. We also found that the survival rate was higher when CPR was done by team members with experience in critical care units. It seems that care provision to critically-ill patients and great experience of CPR in critical care units improve the competence of critical care staff in CPR and thereby improve the post-CPR survival rate. In the present study, the survival rate was lower when the CPR duration was longer. The CAs that need shorter CPRs are usually due to reversible causes, while the CAs that need longer CPRs are generally due to the hypoperfusion and hypoxic injury of the tissues and, hence, have poorer outcomes [6, 46]. We also found a significant difference in CPR team performance based on CPR outcomes. Non-technical skills such as communication, leadership, and teamwork significantly influence CPR quality [17, 18]. Poor leadership, communication, and teamwork in CPR teams may lead to permanent disabilities and even death in patients [22].

This study had some limitations. It was conducted only in teaching hospitals of Zanjan City with a relatively small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. The potential for observer bias should also be acknowledged, as team members were aware of the observer’s presence.

In conclusion, the CPR team members in teaching hospitals in Zanjan have relatively poor non-technical skills, particularly in leadership. Strategies such as reducing the time between call and arrival, ensuring adequate experience of team members, field monitoring of team performance, and appointing competent team leaders can be used to improve CPR team performance and thus CPR outcomes. Educational programs and workshops on teamwork and leadership as well as environmental improvements such as dedicated elevators for CPR team are also recommended. The findings of this study can be used to restructure in-hospital CPR teams and develop interventions for teamwork improvement.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study WAS approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran (Code: IR.ZUMS.REC.1403.057). Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all the participants before enrolment.

Funding

This research was funded by Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Study design, data analysis, and writing the initial draft: All authors; Data collection: Yadolah Shirvani; Review and editing: Yadolah Shirvani, Mohammad Ali Yadegari, Abdolhossein Emami-Sigaroudi, and Fatemeh Masaebi. Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and the management of the selected hospitals for their cooperation, and the Deputy for Research of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences for the financial support.

Cardiac Arrest (CA) is a leading cause of death worldwide. It refers to the sudden cessation of systemic blood circulation and spontaneous breathing. It usually occurs without significant warning signs [1-3] and is accompanied by a cardiac dysrhythmia. The mean age of individuals with CA is around 65 years, with at least 40% under 65 years of age [4]. Each year, 350000–450000 individuals in the United States and 700000 in Europe experience CA [5, 6]. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) is the most important measure for CA management, and its outcomes depend on the timely performance of basic and advanced life support measures [7], CPR duration, underlying disease, the timely use of a cardiac defibrillator, and the CPR team members’ knowledge and skillfulness [8]. Despite continuous revisions and improvements of CPR guidelines, only 6–9% of patients survive after CPR [9]. The CPR success rate in Iran for in-hospital CA varies from 2% to 27% across different studies [10-12]. CPR is a team-based measure, and its quality and success rely not only on team members’ technical skills, but also on their non-technical skills [13] such as coordination, collaboration, communication, leadership, and teamwork [14] that allow team members to effectively work together and attain their common goals [15]. It is a determining factor of emergency condition management, and its ineffectiveness may negatively affect patient and public safety [16, 17].

The leader of the CPR team is usually a competent physician who determines the CPR plan [18]. According to the European Resuscitation Council (ERC), team structure, dynamics, and leadership significantly influence the performance of the interdisciplinary healthcare team during resuscitation [19]. Poor teamwork during CPR endangers patient safety, negatively affects CPR outcomes [20, 21], and may lead to lifelong disabilities or death in patients [22]. Several factors can affect the CPR team’s performance, including culture, resources, education, guidelines, and team communication [23-25]. Although CPR guidelines emphasize non-technical skills, they lack strategies for improving teamwork, leadership, and communication [24]. Some studies reported that 70–80% of medical errors are due to poor communication and teamwork [25, 26]. Moreover, the conditions of patients and their companions, as well as intra- and extra-organizational factors, can affect teamwork [27]. Other effective factors include CPR onset delay, members’ limited experience and skills, equipment shortages, environmental conditions, patients’ conditions, and family actions [28].

To the best of our knowledge, there is scant research that has evaluated the performance of the in-hospital CPR team in Iran. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the performance of the CPR team in teaching hospitals of Zanjan, Iran, and find its influential factors.

Materials and Methods

This observational descriptive-analytical study was conducted from June 2024 to February 2025 in two teaching hospitals affiliated with Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran. There were CPR teams working for 24 hours in these two hospitals with a predetermined monthly schedule and CPR announcement equipment. The team leaders were clinically competent, either physicians or specialty residents (e.g. emergency medicine, cardiology, anesthesiology, or internal medicine). The study population consisted of all CPR events performed in the hospitals. Using a census sampling method, all eligible CPR events during the study period were included. The sample size was determined to be at least 50 CPRs, based on a previous study reporting a Standard Deviation (SD) of 3.6 for teamwork scores, and considering a 5% significance level and a precision of 1 [29]. Inclusion criteria were CPRs for patients >18 years, CPR team size >3, and CPR duration >5 minutes. Incomplete documentation of CPR measures (the cases where the assessor could not determine the exact time and method of initiation because they were not present for direct observation from the very beginning) was the exclusion criterion.

The data collection instrument was the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM), supplemented by a demographic form designed to record relevant information of both patients and CPR team members. The TEAM was developed by Cooper et al. for the assessment of teamwork in emergency conditions [30]. It has 11 items measuring three non-technical teamwork skills, including leadership (n=2), teamwork (n=7), and task management (n=2), and one item measuring global teamwork performance. The items are rated on a scale from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“almost always”). The total score of the instrument ranges from 0 to 44. Scores ≤33, 34–39, and 40–44 indicate poor, good, and excellent team performance, respectively. The total score of the global teamwork performance rating is 0–10; scores <7 and 9–10 indicate poor and excellent global performance, respectively [31]. Previous studies have confirmed the psychometric properties of the TEAM [32-34]. In our study, it was first translated into Persian and culturally adapted using a standard forward–backward method by two bilingual experts. Face and content validity were then evaluated by a panel of experts (n=10), including specialists in emergency medicine and cardiology. Both the Scale-Content Validity Index (S-CVI) and the average of Item-Content Validity Indices (S-CVI/Ave) were 0.92. Reliability was assessed in a pilot study on 10 CPR events. Two independent raters scored each event simultaneously. Inter-rater reliability was 0.87, indicating strong agreement, and internal consistency, measured by Cronbach’s α, was 0.90.

For data collection, an independent rater visited the wards where CPRs were conducted during different work shifts. To minimize observer bias, the rater was introduced to the CPR team as a helping assistant to the supervisor, concealing their primary role as a research assessor. The rater observed eligible CPRs and completed the TEAM questionnaire immediately after each CPR concluded, ensuring the team remained unaware of the formal evaluation. SPSS software, version 27 was employed for data analysis. Categorical variables were described using frequency and percentage measures, and numerical variables were described using Mean±SD, median, and interquartile range. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test revealed that some variables did not follow a normal distribution (P<0.05). Therefore, non-parametric methods, including Spearman’s correlation test and Mann-Whitney U test, were used for data analysis.

Results

This study evaluated the non-technical skills of 290 CPR team members across 50 in-hospital CA events. The resuscitated patients were aged 57–82 years with a mean age of 71.38±6.68 years. Most patients were male (60%), and the most common leading cause of CPR was cardiac disease (74%). Their other characteristics are presented in Table 1.

The total TEAM score of the CPR team was 30.2±7.02. The domain with the highest mean score was task management (5.88±1.45), while the lowest was leadership (4.84±1.71). The mean teamwork score was 19.48±4.4. Among the items, the lowest mean score was for item No.1 (2.32±0.98) and the highest mean score was for item No.10 (3.16±0.76) (Table 2).

As shown in Table 3, the total TEAM score had a significant negative relationship with patient age (r=–0.43, P=0.002), denoting poorer team performance for elderly patients.

Moreover, the teamwork domain of TEAM showed a significant negative relationship with the number of team members (r=–0.303, P=0.033), suggesting poorer performance by larger CPR teams. The call-to-arrival interval also had a significant negative relationship with the total TEAM score (r=–0.582, P=0.001), indicating that longer intervals were associated with poorer CPR team performance. On the other hand, CPR team members’ work experience in critical care units had a significant positive relationship with the teamwork domain score (r=0.323, P=0.022).

According to the Mann–Whitney U test results (Table 4), the TEAM score was significantly different based on CPR outcomes (patient survival/death).

Those with patient survival outcome had significantly higher scores in leadership (P=0.001), teamwork (P=0.001), task management (P=0.001), overall performance (P=0.001), and global rating (P=0.002), indicating that better team performance was related to more favorable CPR outcomes. Furthermore, clinicians who contributed to patient survival had significantly more extensive work experience, both in critical care units (P=0.001) and in hospitals (P=0.011). This indicates that greater clinical experience may be a critical factor contributing to effective team performance and, consequently, successful CPR. In contrast, for the CPR events with patient death outcome, there was a larger team size (P=0.001), longer call-to-arrival interval (P=0.001), longer CPR durations (P=0.001), and older patients (P=0.001). These findings imply that delays in response, extended resuscitation, larger team sizes, and high patient age may be negatively associated with CPR success. No statistically significant difference in CPR outcomes (survival and death) was found based on team members’ age.

Discussion

This study evaluated the performance of the CPR team in teaching hospitals of Zanjan, the CPR outcomes, and influential factors for 50 in-hospital CPRs. The lowest performance score was found in the leadership domain, underscoring significant challenges in CPR team leadership, particularly in the absence of a designated team leader. CPR leadership is one of the most important factors in efficient CPR team performance [35]; CPR teams with better leadership deliver higher-quality CPR and faster defibrillation [15]. The American Heart Association (AHA) and the ERC recommend incorporating teamwork and leadership education into educational programs on advanced life support and resuscitation [36, 37]. For the item “the team prioritized tasks”, the highest score was reported. The AHA guideline also emphasizes the importance of teamwork and task prioritization [36].

Study findings revealed that a larger CPR team size was associated with poorer non-technical skills. Therefore, it seems that large CPR team size negatively affects team performance, leadership, and communication. This may be due to the poorer communication clarity and poorer team coordination in larger CPR teams. The AHA recommends that CPR teams should include at least two members, while larger teams consisting of 3-5 members may have better performance [38]. In agreement with our findings, a study reported a significant negative relationship between CPR team size and CPR team performance, indicating that larger teams have poorer team performance [31]. Moreover, we found a significant negative relationship between CPR team size and patient survival, suggesting that larger teams are associated with lower patient survival. Coordination and collaboration among members are probably more difficult in larger teams; medium-sized teams consisting of 3-5 members may produce the best outcomes.

An inverse relationship was also observed between patient age and CPR team performance, suggesting that teams may perform less effectively when resuscitating older patients. This finding is consistent with those of previous reports [37, 39]. The lower survival rates among older adults likely reflect the greater burden of comorbid conditions in this population [40, 41]. There was a significant negative relationship between CPR team performance and the time from call to patient arrival. The recorded time in our study generally fell within the critical golden period for initiating CPR following CA. Maintaining intervention within this crucial window is vital for preserving neurological function and preventing irreversible damage to vital organs. Timely CPR onset and defibrillation are important to reduce the rates of post-CA complications and death. This is supported by evidence indicating a marked decline in survival likelihood with progressively delayed resuscitation efforts [21]. Nurses’ long delays in starting CPR and using a defibrillator may indicate that they, as the first responders to CA, may fail to transform their knowledge and skills into timely and effective measures. In our study, the call–hospital arrival interval also had a significant relationship with survival rate, denoting that a shorter interval was associated with greater CPR success. Similarly, a previous study reported that call–arrival time had a significant effect on CPR success [42]. It seems that the timely arrival of CPR team members is associated with greater coherence, coordination, motivation, and self-confidence, thereby increasing the CPR success rate.

The findings demonstrated that CPR team performance was higher among team members with greater work experience in critical care units. The CPR team members’ knowledge and skills can affect CPR outcomes [43]. A study found that the survival rate after CPR performed by CPR specialists was higher than that performed by non-specialized staff [44]. Another study demonstrated that implementation of CPR by specialized skilled teams significantly improved patient survival rates [45]. We also found that the survival rate was higher when CPR was done by team members with experience in critical care units. It seems that care provision to critically-ill patients and great experience of CPR in critical care units improve the competence of critical care staff in CPR and thereby improve the post-CPR survival rate. In the present study, the survival rate was lower when the CPR duration was longer. The CAs that need shorter CPRs are usually due to reversible causes, while the CAs that need longer CPRs are generally due to the hypoperfusion and hypoxic injury of the tissues and, hence, have poorer outcomes [6, 46]. We also found a significant difference in CPR team performance based on CPR outcomes. Non-technical skills such as communication, leadership, and teamwork significantly influence CPR quality [17, 18]. Poor leadership, communication, and teamwork in CPR teams may lead to permanent disabilities and even death in patients [22].

This study had some limitations. It was conducted only in teaching hospitals of Zanjan City with a relatively small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. The potential for observer bias should also be acknowledged, as team members were aware of the observer’s presence.

In conclusion, the CPR team members in teaching hospitals in Zanjan have relatively poor non-technical skills, particularly in leadership. Strategies such as reducing the time between call and arrival, ensuring adequate experience of team members, field monitoring of team performance, and appointing competent team leaders can be used to improve CPR team performance and thus CPR outcomes. Educational programs and workshops on teamwork and leadership as well as environmental improvements such as dedicated elevators for CPR team are also recommended. The findings of this study can be used to restructure in-hospital CPR teams and develop interventions for teamwork improvement.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study WAS approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran (Code: IR.ZUMS.REC.1403.057). Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all the participants before enrolment.

Funding

This research was funded by Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Study design, data analysis, and writing the initial draft: All authors; Data collection: Yadolah Shirvani; Review and editing: Yadolah Shirvani, Mohammad Ali Yadegari, Abdolhossein Emami-Sigaroudi, and Fatemeh Masaebi. Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and the management of the selected hospitals for their cooperation, and the Deputy for Research of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences for the financial support.

References

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2022 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022; 145(8):e153-e639. [DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052] [PMID]

- Dinavari MF, Paknezhad SP, Sheikhalipour Z, Yousefi F, Beheshtirouy S, Jafarinodeh B, et al. Evaluation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation for patient outcomes in Imam Reza General Hospital Tabriz, Iran. J Res Clin Med. 2024; 12:23. [DOI:10.34172/jrcm.33373]

- Kabiri N, Hajebrahimi S, Soleimanpour M, Ardebili RA, Kashgsaray NH, Soleimanpour H. Basic life support training for intensive care unit nurses at a general hospital in Tabriz, Iran: A best practice implementation project. JBI Evid Implement. 2025; 23(2):153-62. [DOI:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000434] [PMID]

- Soleimanpour H, Behringer W, Tabrizi JS, Sarahrudi K, Golzari S, Hajdu S, et al. An analytical comparison of the opinions of physicians working in emergency and trauma surgery departments at Tabriz and Vienna medical universities regarding family presence during resuscitation. PLoS One. 2015; 10(4):e0123765. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0123765] [PMID]

- Khoshbaten M, Soleimanpour H, Ala A, Shams Vahdati S, Ebrahimian K, Safari S, et al. Which form of medical training is the best in improving Interns’ knowledge related to advanced cardiac life support drugs pharmacology? An educational analytical intervention study between electronic learning and lecture-based education. Anesth Pain Med. 2014; 4(1):e15546. [DOI:10.5812/aapm.15546] [PMID]

- Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabañas JG, Donnino MW, Drennan IR, Hirsch KG, et al. Part 3: Adult basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020; 142(16_suppl_2):S366-S468. [PMID]

- Perkins GD, Gräsner JT, Semeraro F, Olasveengen T, Soar J, Lott C, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: Executive summary. Resuscitation. 2021; 161:1-60. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.003] [PMID]

- Dyson K, Bray J, Smith K, Bernard S, Finn JJR. A systematic review of the effect of emergency medical service practitioners’ experience and exposure to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest on patient survival and procedural performance. Resuscitation. 2014; 85(9):1134-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.05.020] [PMID]

- Finke SR, Schroeder DC, Ecker H, Wingen S, Hinkelbein J, Wetsch WA, et al. Gender aspects in cardiopulmonary resuscitation by schoolchildren: A systematic review. Resuscitation. 2018; 125:70-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.01.025] [PMID]

- Citolino CM, Santos ES, Silva Rde C, Nogueira Lde S. [Factors affecting the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in inpatient units: Perception of nurses (Portuguese)]. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2015; 49(6):908-14. [DOI:10.1590/S0080-623420150000600005] [PMID]

- Fishman GI, Chugh SS, DiMarco JP, Albert CM, Anderson ME, Bonow RO, et al. Sudden cardiac death prediction and prevention: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Heart Rhythm Society Workshop. Circulation. 2010; 122(22):2335-48. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976092] [PMID]

- Giacoppo D. Impact of bystander-initiated cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: where would you be happy to have a cardiac arrest?. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40(3):319-21. [DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy911] [PMID]

- Dirks JL. Effective strategies for teaching teamwork. Crit Care Nurse. 2019; 39(4):40-7. [DOI:10.4037/ccn2019704] [PMID]

- Lauridsen KG, Watanabe I, Løfgren B, Cheng A, Duval-Arnould J, Hunt EA, et al. Standardising communication to improve in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2020; 147:73-80. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.12.013] [PMID]

- Weaver SJ, Dy SM, Rosen MA. Team-training in healthcare: A narrative synthesis of the literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014; 23(5):359-72.[DOI:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001848] [PMID]

- Johnson SL, Haerling KA, Yuwen W, Huynh V, Le C. Incivility and clinical performance, teamwork, and emotions: A randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Care Qual. 2020; 35(1):70-6. [DOI:10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000407] [PMID]

- Hosseini M, Heydari A, Reihani H, Kareshki H. Elements of teamwork in resuscitation: An integrative review. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2022; 10(3):95-102. [DOI:10.30476/BEAT.2021.91963.1291] [PMID]

- Soar J, Böttiger BW, Carli P, Couper K, Deakin CD, Djärv T, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2021; 161:115-51. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.010] [PMID]

- Greif R, Lockey A, Breckwoldt J, Carmona F, Conaghan P, Kuzovlev A, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: Education for resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2021; 161:388-407. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.016] [PMID]

- Freytag J, Stroben F, Hautz WE, Schauber SK, Kämmer JE. Rating the quality of teamwork-a comparison of novice and expert ratings using the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM) in simulated emergencies. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019; 27(1):12. [DOI:10.1186/s13049-019-0591-9] [PMID]

- Hunziker S, Johansson AC, Tschan F, Semmer NK, Rock L, Howell MD, et al. Teamwork and leadership in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57(24):2381-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.017] [PMID]

- Boet S, Etherington C, Larrigan S, Yin L, Khan H, Sullivan K, et al. Measuring the teamwork performance of teams in crisis situations: A systematic review of assessment tools and their measurement properties. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019; 28(4):327-37. [DOI:10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008260] [PMID]

- Perry MF, Seto TL, Vasquez JC, Josyula S, Rule ARL, Rule DW, et al. The influence of culture on teamwork and communication in a simulation-based resuscitation training at a community hospital in Honduras. Simul Healthc. 2018; 13(5):363-370. [DOI:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000323] [PMID]

- Lauridsen KG, Krogh K, Müller SD, Schmidt AS, Nadkarni VM, Berg RA, et al. Barriers and facilitators for in-hospital resuscitation: A prospective clinical study. Resuscitation. 2021; 164:70-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.05.007] [PMID]

- Cheng A, Nadkarni VM, Mancini MB, Hunt EA, Sinz EH, Merchant RM, et al. Resuscitation education science: educational strategies to improve outcomes from cardiac arrest: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018; 138(6):e82-122. [DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000583]

- Verspuy M, Van Bogaert P. Interprofessional collaboration and communication. In: Van Bogaert P, Clarke S, editors. The Organizational Context of Nursing Practice. Cham: Springer; 2018. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-71042-6_12]

- Dehghan-Nayeri N, Nouri-Sari H, Bahramnezhad F, Hajibabaee F, Senmar M. Barriers and facilitators to cardiopulmonary resuscitation within pre-hospital emergency medical services: A qualitative study. BMC Emerg Med. 2021; 21(1):120. [DOI:10.1186/s12873-021-00514-3] [PMID]

- Janatolmakan M, Nouri R, Soroush A, Andayeshgar B, Khatony A. Barriers to the success of cardiopulmonary resuscitation from the perspective of Iranian nurses: A qualitative content analysis. Int Emerg Nurs. 2021; 54:100954. [DOI:10.1016/j.ienj.2020.100954] [PMID]

- Saunders R, Wood E, Coleman A, Gullick K, Graham R, Seaman K. Emergencies within hospital wards: An observational study of the non-technical skills of medical emergency teams. Australas Emerg Care. 2021; 24(2):89-95. [DOI:10.1016/j.auec.2020.07.003] [PMID]

- Cooper S, Cant R, Porter J, Sellick K, Somers G, Kinsman L, et al. Rating medical emergency teamwork performance: Development of the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM). Resuscitation. 2010 ;81(4):446-52. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.11.027] [PMID]

- Cooper S, Cant R, Connell C, Sims L, Porter JE, Symmons M, et al. Measuring teamwork performance: validity testing of the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM) with clinical resuscitation teams. Resuscitation. 2016; 101:97-101. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.01.026] [PMID]

- Cant RP, Porter JE, Cooper SJ, Roberts K, Wilson I, Gartside C. Improving the non-technical skills of hospital medical emergency teams: The Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM™). Emerg Med Australas. 2016; 28(6):641-6. [DOI:10.1111/1742-6723.12643] [PMID]

- Hultin M, Jonsson K, Härgestam M, Lindkvist M, Brulin C. Reliability of instruments that measure situation awareness, team performance and task performance in a simulation setting with medical students. BMJ Open. 2019; 9(9):e029412. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029412] [PMID]

- Morian H, Härgestam M, Hultin M, Jonsson H, Jonsson K, Nordahl Amorøe T, et al. Reliability and validity testing of team emergency assessment measure in a distributed team context. Front Psychol. 2023; 14:1110306. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1110306] [PMID]

- Porter JE, Cant RP, Cooper SJ. Rating teams’ non-technical skills in the emergency department: A qualitative study of nurses’ experience. Int Emerg Nurs. 2018; 38:15-20. [DOI:10.1016/j.ienj.2017.12.006] [PMID]

- Magid DJ, Aziz K, Cheng A, Hazinski MF, Hoover AV, Mahgoub M, et al. Part 2: Evidence evaluation and guidelines development: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020; 142(16_Suppl_2):S358-65. [DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000898]

- Hunziker S, O’Connell KJ, Ranniger C, Su L, Hochstrasser S, Becker C, et al. Effects of designated leadership and team-size on cardiopulmonary resuscitation: The Basel-Washington SIMulation (BaWaSim) trial. J Crit Care. 2018; 48:72-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.08.001] [PMID]

- Merchant RM, Topjian AA, Panchal AR, Cheng A, Aziz K, Berg KM, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020; 142(16_Suppl_2):S337-57. [DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000918]

- Montazar SH, Amooei M, Sheyoei M, Bahari M. [Results of CPR and contributing factor in emergency department of sari imam Khomeini hospital, 2011-2013 (Persian)]. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2014; 24(111):53-8. [Link]

- Hiemstra B, Bergman R, Absalom AR, van der Naalt J, van der Harst P, de Vos R, et al. Long-term outcome of elderly out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors as compared with their younger counterparts and the general population. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2018; 12(12):341-9. [DOI:10.1177/1753944718792420] [PMID]

- Girotra S, Tang Y, Chan PS, Nallamothu BK, American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigators. Survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest in critically ill patients: Implications for COVID-19 outbreak? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020; 13(7):e006837. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006837] [PMID]

- Andersen LW, Holmberg MJ, Berg KM, Donnino MW, Granfeldt A. In-hospital cardiac arrest: A review. JAMA. 2019; 321(12):1200-10. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2019.1696] [PMID]

- Shams A, Raad M, Chams N, Chams S, Bachir R, El Sayed MJ. Community involvement in out of hospital cardiac arrest: A cross-sectional study assessing cardiopulmonary resuscitation awareness and barriers among the Lebanese youth. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95(43):e5091. [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000005091] [PMID]

- Abu Fraiha Y, Shafat T, Codish S, Frenkel A, Dolfin D, Dreiher J, et al. Outcomes of in-hospital cardiac arrest managed with and without a specialized code team: A retrospective observational study. PLoS One. 2024; 19(9):e0309376. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0309376] [PMID]

- Konrad D, Jäderling G, Bell M, Granath F, Ekbom A, Martling CR. Reducing in-hospital cardiac arrests and hospital mortality by introducing a medical emergency team. Intensive Care Med. 2010; 36(1):100-6. [DOI:10.1007/s00134-009-1634-x] [PMID]

- Amacher SA, Bohren C, Blatter R, Becker C, Beck K, Mueller J, et al. Long-term survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2022; 7(6):633-43. [DOI:10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0795] [PMID]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2025/07/8 | Accepted: 2026/01/11 | Published: 2026/01/11

Received: 2025/07/8 | Accepted: 2026/01/11 | Published: 2026/01/11

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |