Wed, Jan 28, 2026

Volume 36, Issue 1 (1-2026)

JHNM 2026, 36(1): 26-36 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Chatraei R, Bostani Khalesi Z, Rahnavardi M, Maroufizadeh S. Respectful Maternity Care and Associated Factors among Women from North of Iran. JHNM 2026; 36 (1) :26-36

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2481-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2481-en.html

1- Midwifery (MSc), Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Professor, Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,z_bostani@yahoo.com

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- Associated Professor, Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Professor, Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- Associated Professor, Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 523 kb]

(41 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (106 Views)

References

Full-Text: (4 Views)

Introduction

Pregnancy and childbirth are important events in women’s lives [1]. Access to high-quality, Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) is a basic right for women [2]. Over the last few decades, this accessibility has encouraged women to give birth in hospitals [3]. Achieving the sustainable development goals of reducing maternal mortality to less than 70 per 100,000 births and reducing infant mortality to less than 12 per 1,000 live births by 2030 requires providing safe and high-quality RMC to mothers. Despite the emphasis, considerable progress has not been made toward these goals due to inadequate adherence to aspects of RMC [4]. Women still experience disrespect and abuse during labor and birth [5]. The prevalence of this disrespect and abuse has been reported to be 36.3% in the Netherlands [6], 77.6% in Germany [7], 17.3% in America [8], 71% in India [9], and 75.7% in Iran [10].

Lack of observing the principles of high-quality RMC and existence of physical or verbal abuse, discrimination, vaginal examinations without permission, or procedures such as episiotomy and induction of labor can lead to a sense of worthlessness, induces weakness to the woman, and causes an increase in negative and maternal and neonatal outcomes [3], including postpartum depression [11], reduced desire for subsequent pregnancies, and increased intervals between pregnancies [1]. Generally, owing to the extensive negative outcomes of failing to provide RMC, active organizations in the health sector emphasized this aspect of maternity care as one of the most significant factors in high-quality, standard care and proposed it as an objective and measurable quality of maternal and neonatal care [12].

Very limited studies had been conducted in the area of abuse and disrespect towards women in maternity centers in previous decades. Bowser and Hill called for collective action on this issue, which led to greater attention to the mother’s experiences during childbirth and expanded the studies in this area [13]. After that, the White Ribbon Alliance formed a community to develop the RMC charter [14]. The World Health Organization (WHO) presented an RMC-related statement to prevent the disrespect and abuse of mothers during birth [15]. Care with respect for the dignity, privacy, and confidentiality of women provides the conditions for continuous support during labor and birth for the mother, and prevents disrespect and abuse [16].

Autonomy is also a crucial part of RMC and means a woman’s right to decide how to care for herself [17]. In this regard, an interaction between women and healthcare providers is needed [18], which can improve communication, increase the quality of maternity care, and ultimately increase women’s satisfaction with health services [19]. The satisfaction that results from increasing women’s willingness to receive health care can reduce maternal mortality and represent an effective step toward achieving the third goal of sustainable development [20]. The fear of being disrespected by healthcare providers has been mentioned as one of the reasons why many women refuse to receive services; women who experience disrespect in healthcare centers may encourage others not to use these services [21]. Given the significant role of RMC in a positive childbirth experience and the need to identify related factors to improve this experience, this study aimed to determine RMC and its associated factors among women who gave birth in hospitals of Guilan, northern Iran.

Materials and Methods

This analytical cross-sectional study was conducted on 317 women referred to the postpartum department of public hospitals in Guilan Province. As a general rule of thumb for linear regression analysis, at least 10-20 subjects are needed per independent (predictor) variable to conduct the regression analyses [22]. Therefore, the sample size was set at 315, with 15 subjects per independent variable and 21 individual, social, and fertility variables. Multi-stage, non-random sampling was used to select participants. Six hospitals were selected from the east, west, and center of Guilan Province. Sample selection was gradually conducted from each hospital based on the number of childbirths at that hospital The inclusion criteria were consent to participate in the study, normal vaginal delivery, no major abnormalities in the neonate, not taking antidepressants in the last year, not experiencing a stressful event (such as divorce, death of first-degree relatives, or diagnosis of an incurable disease in a family member in the last three months), no mental disability, no deafness, and the ability to speak. These criteria were assessed based on the self-report. Failure to fully answer the questions in the questionnaire was considered an exclusion criterion.

The data collection tools were a questionnaire surveying sociodemographic/obstetric characteristics and the RMC questionnaire [23]. The sociodemographic characteristics included age, educational level, occupation, having a companion during childbirth, ethnicity, place of residence, and household income. The obstetric characteristics included the number of pregnancies, type of pregnancy (planned/unplanned), receiving prenatal care, length of stay in the maternity ward, number of healthcare providers during childbirth, receiving childbirth pain relief medications, the childbirth time (morning, evening, or night shift), and its agent (on-call or resident physician, midwife, midwifery student, gynecological resident). The RMC questionnaire has 15 items and 4 domains, including friendly care (7 items), abuse-free care (3 items), timely care (3 items), and discrimination-free care (2 items). In this study the items are rated as 5 (strongly agree), 4 (agree), 3 (I don’t know), 2 (disagree), and 1 (strongly disagree). The high scores indicate a more positive experience of RMC during childbirth. The scores are reported as percentages. The questionnaires were completed 6-8 hours after childbirth through interviews with the women, after explaining the study objectives to them, and ensuring the confidentiality of their information.

The qualitative variables are described as frequency (percentage), and quantitative variables are described as Mean±SD. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the data distribution. In the univariate analyses, Pearson’s correlation test, independent t-test, and one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used to investigate the relationship between RMC scores and sociodemographic/obstetric characteristics of hospitalized women. Correlation coefficient values of 0.1-0.3, 0.3-0.5, and >0.5 indicate weak, moderate, and strong correlation, respectively. In a multivariate analysis, linear regression was used to identify factors predicting RMC in hospitalized women. The data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 16, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

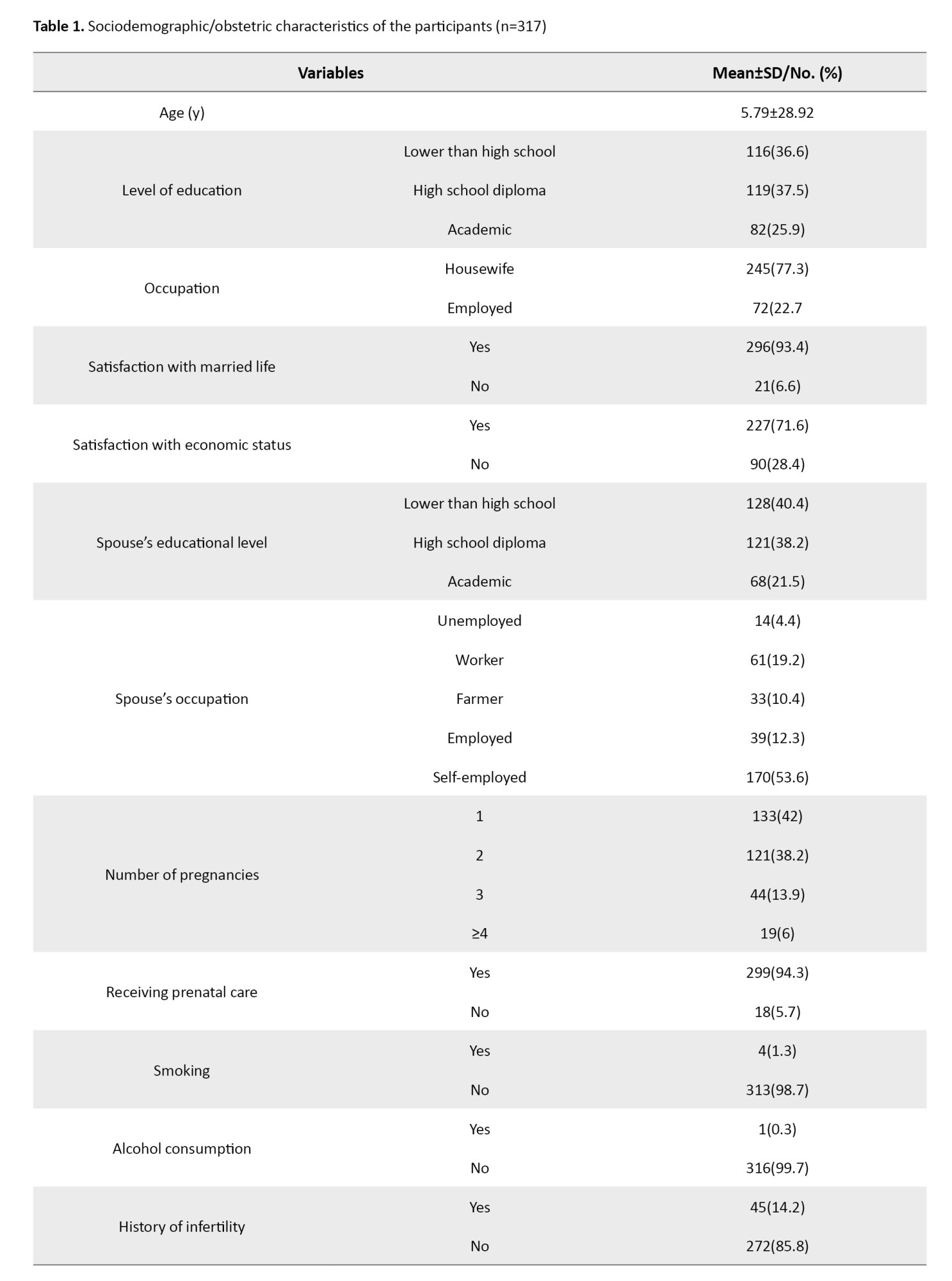

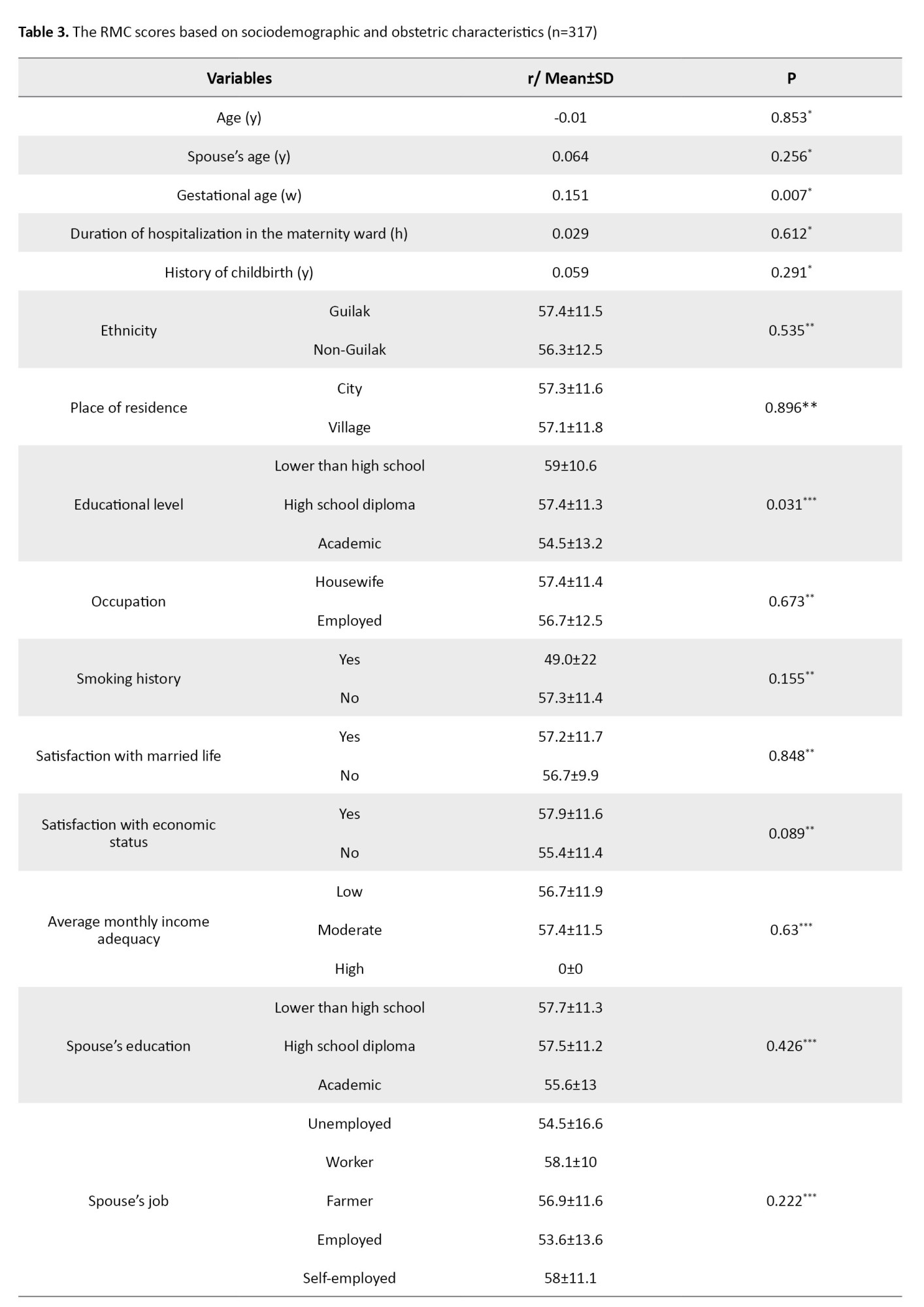

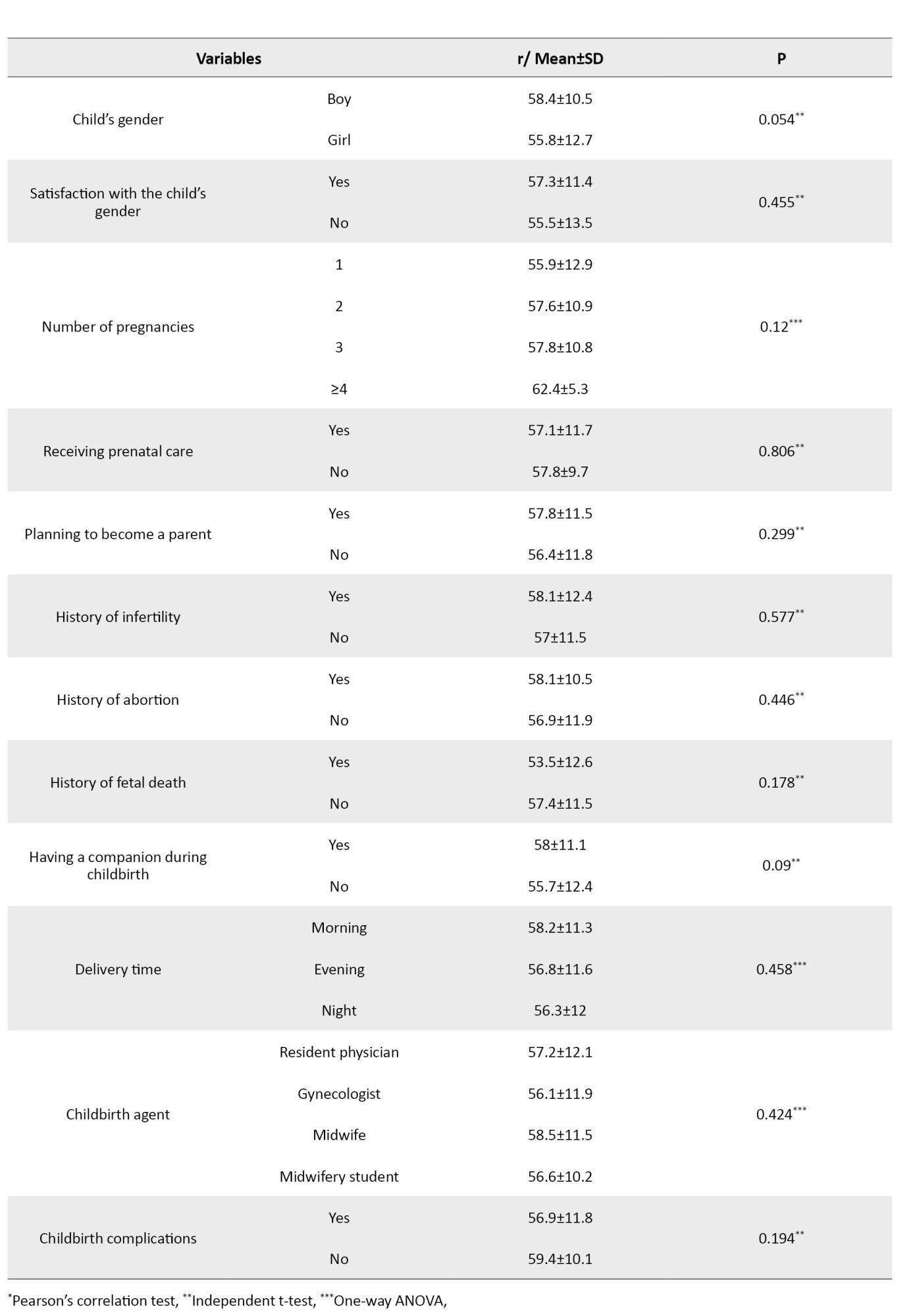

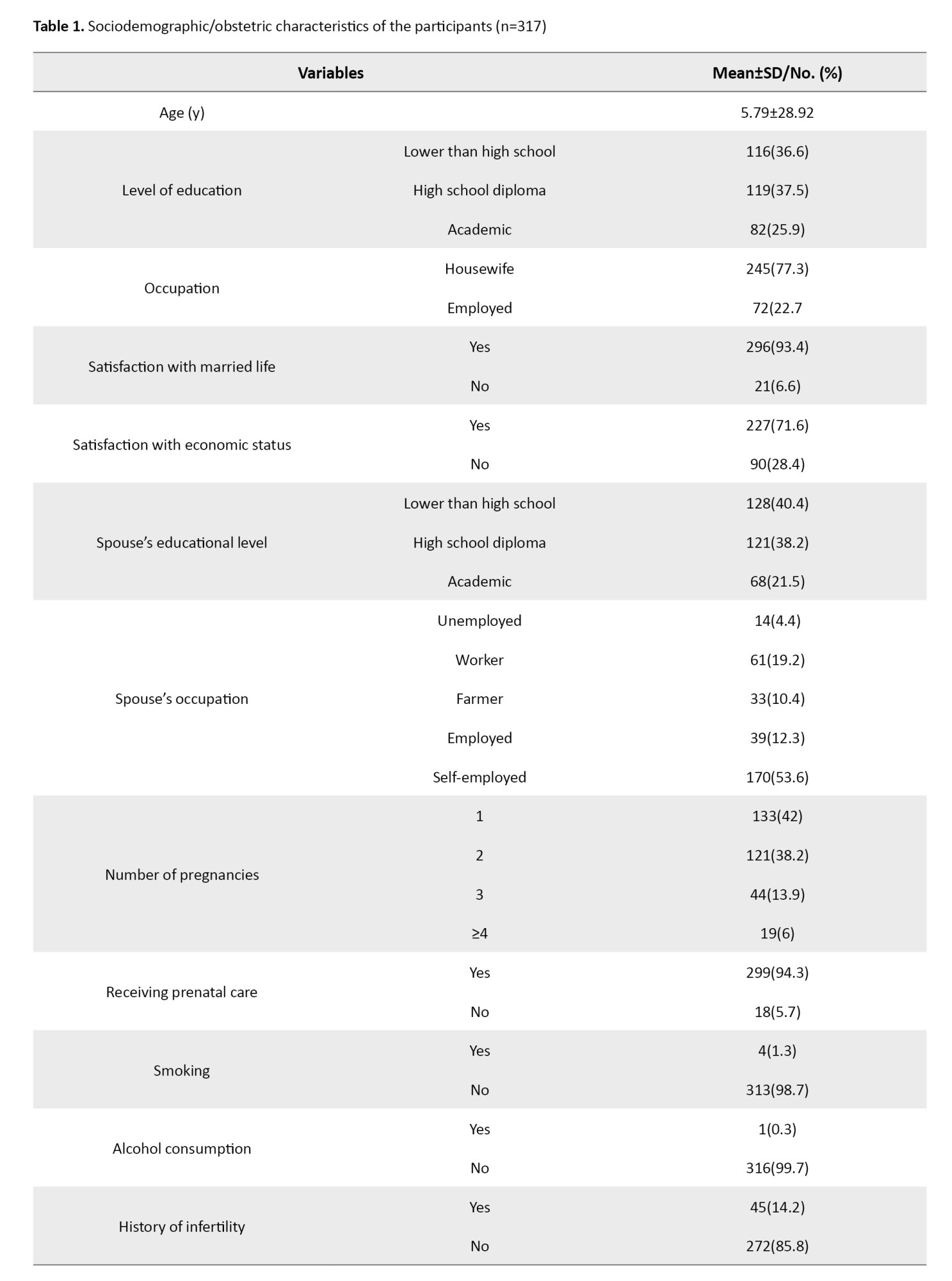

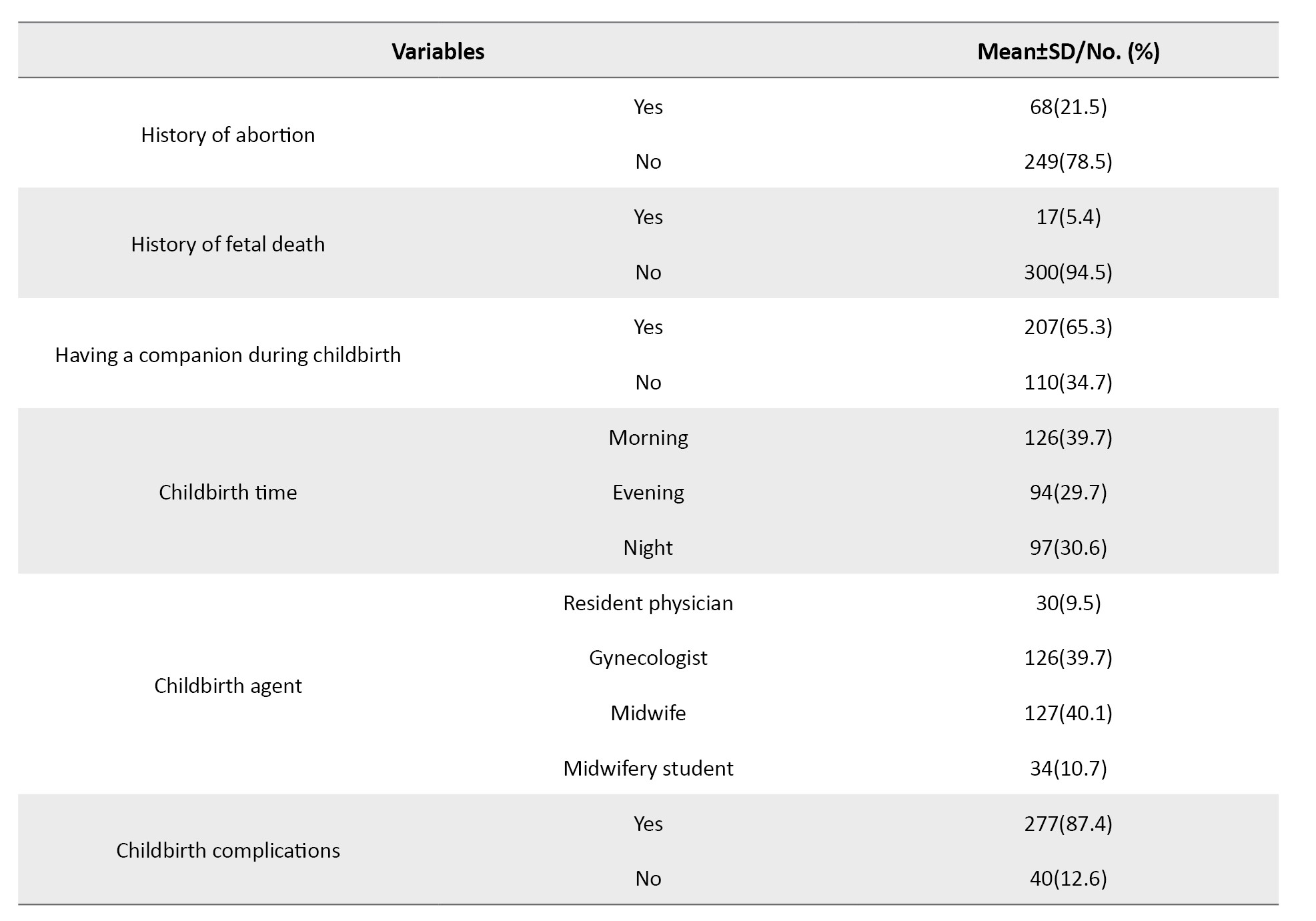

The mean age of women and their husbands was 28.92±5.79 and 33.03±5.63 years, respectively. The educational levels of 82 women (25.9%) and the husbands of 68 women (21.5%) were academic. Also, 22.7% of women were employed, and the husbands of 53.6% of women were self-employed. Moreover, 71% of women reported sufficient income, 84.9% were from the Guilak ethnicity, and 63.4% were living in urban areas. Other characteristics are presented in Table 1.

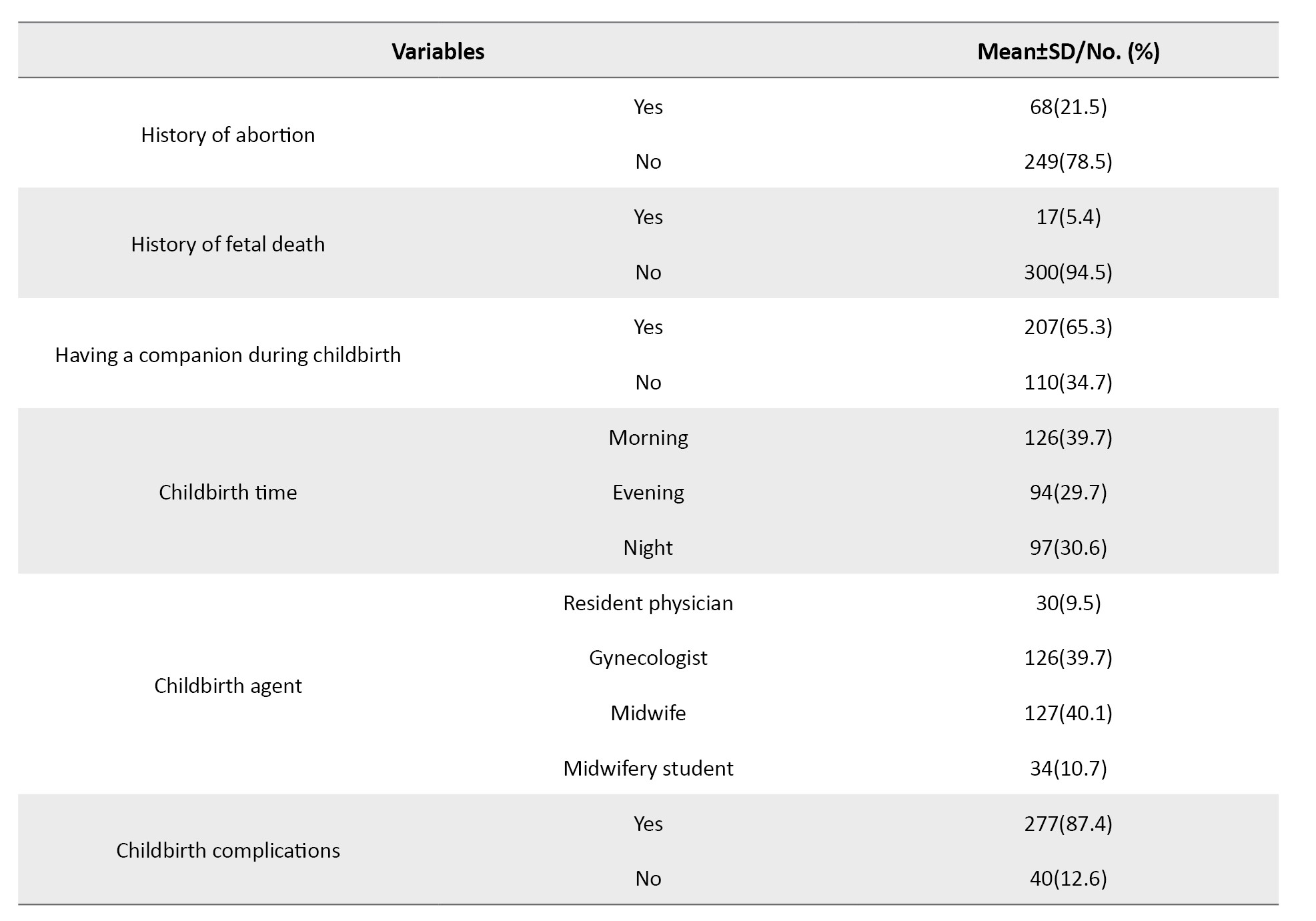

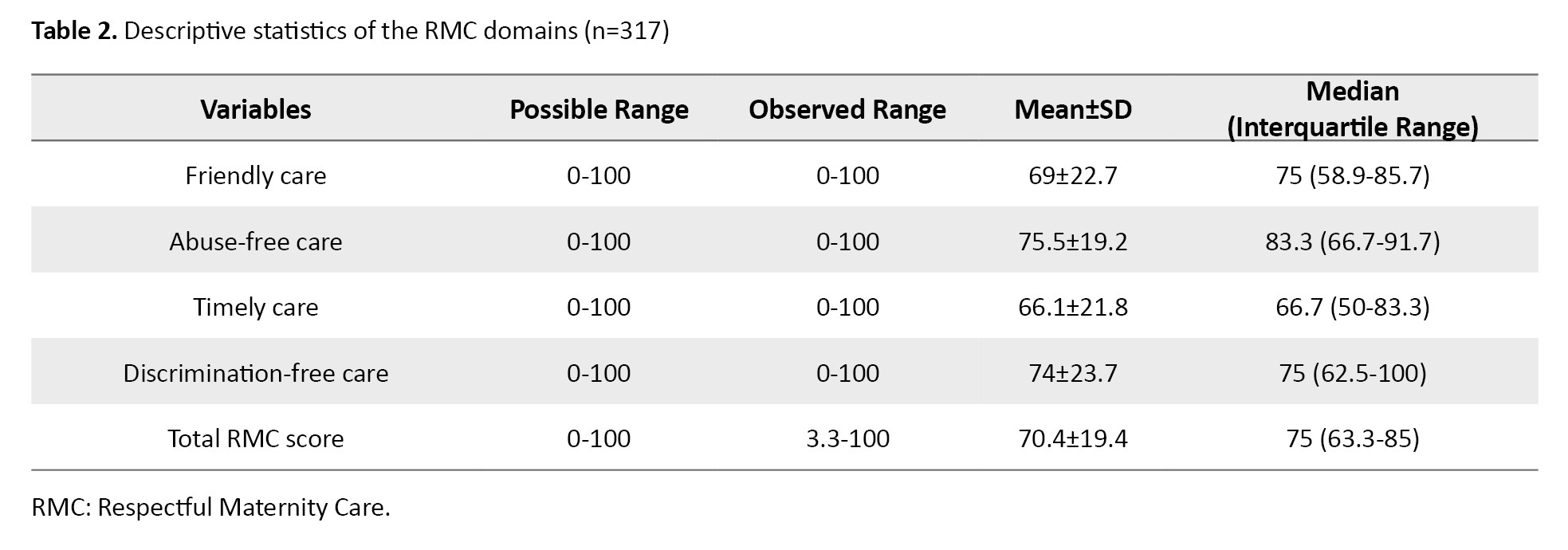

The mean total RMC score was 70.4±19.4, and the median score was 75 (interquartile range: 63.3-85.0). Based on these values, 75% of women reported an RMC score greater than 63.3 (Table 2).

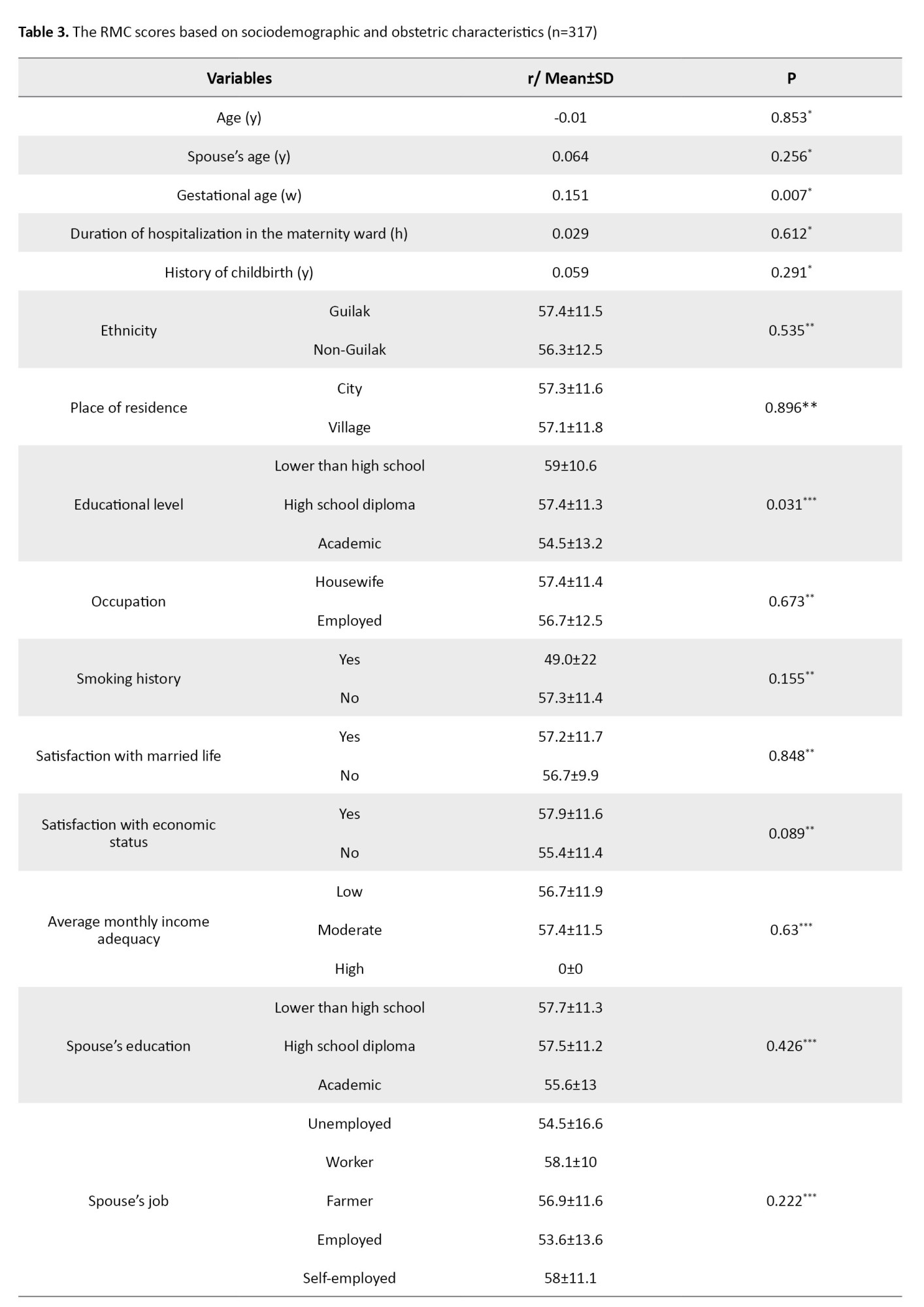

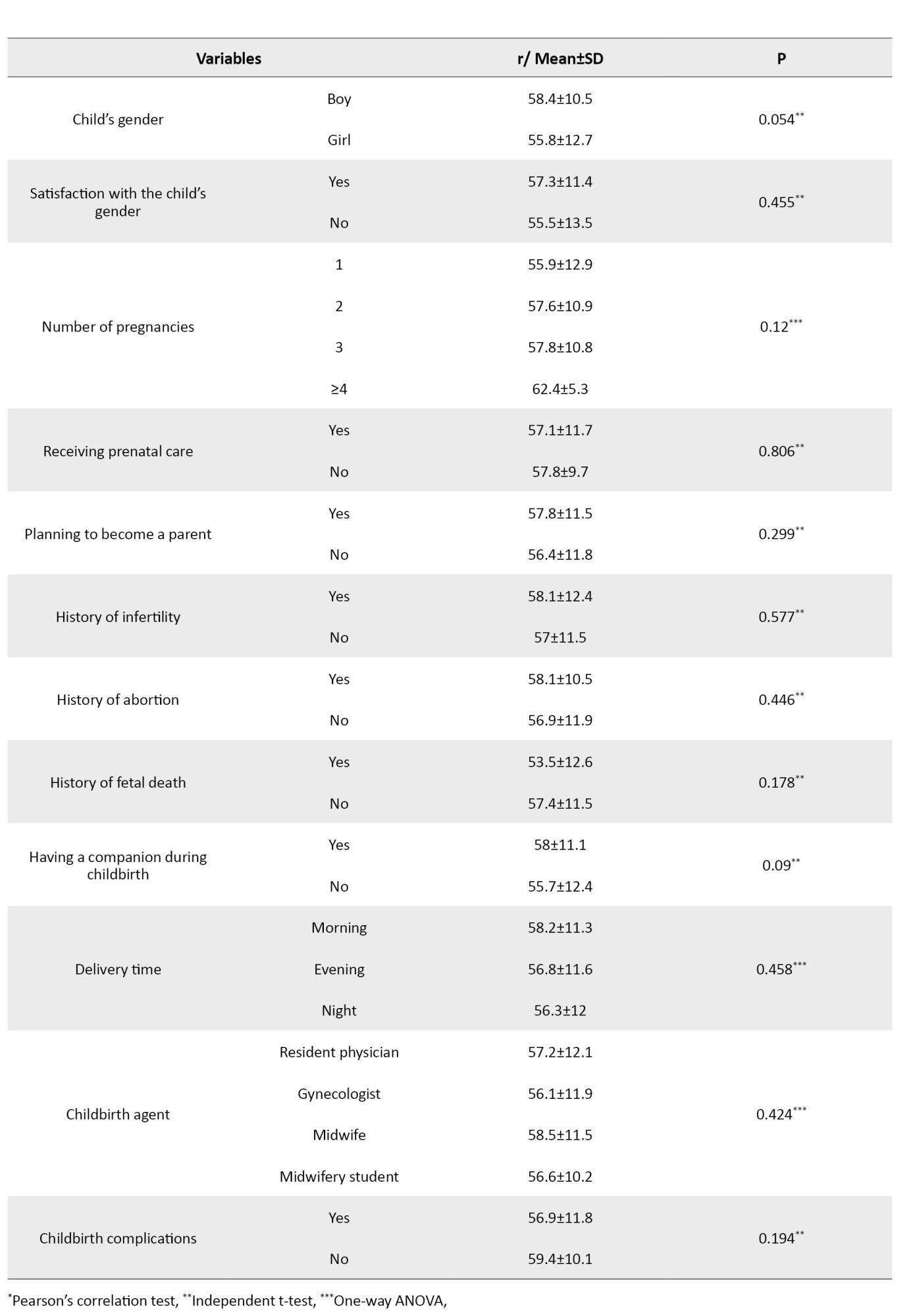

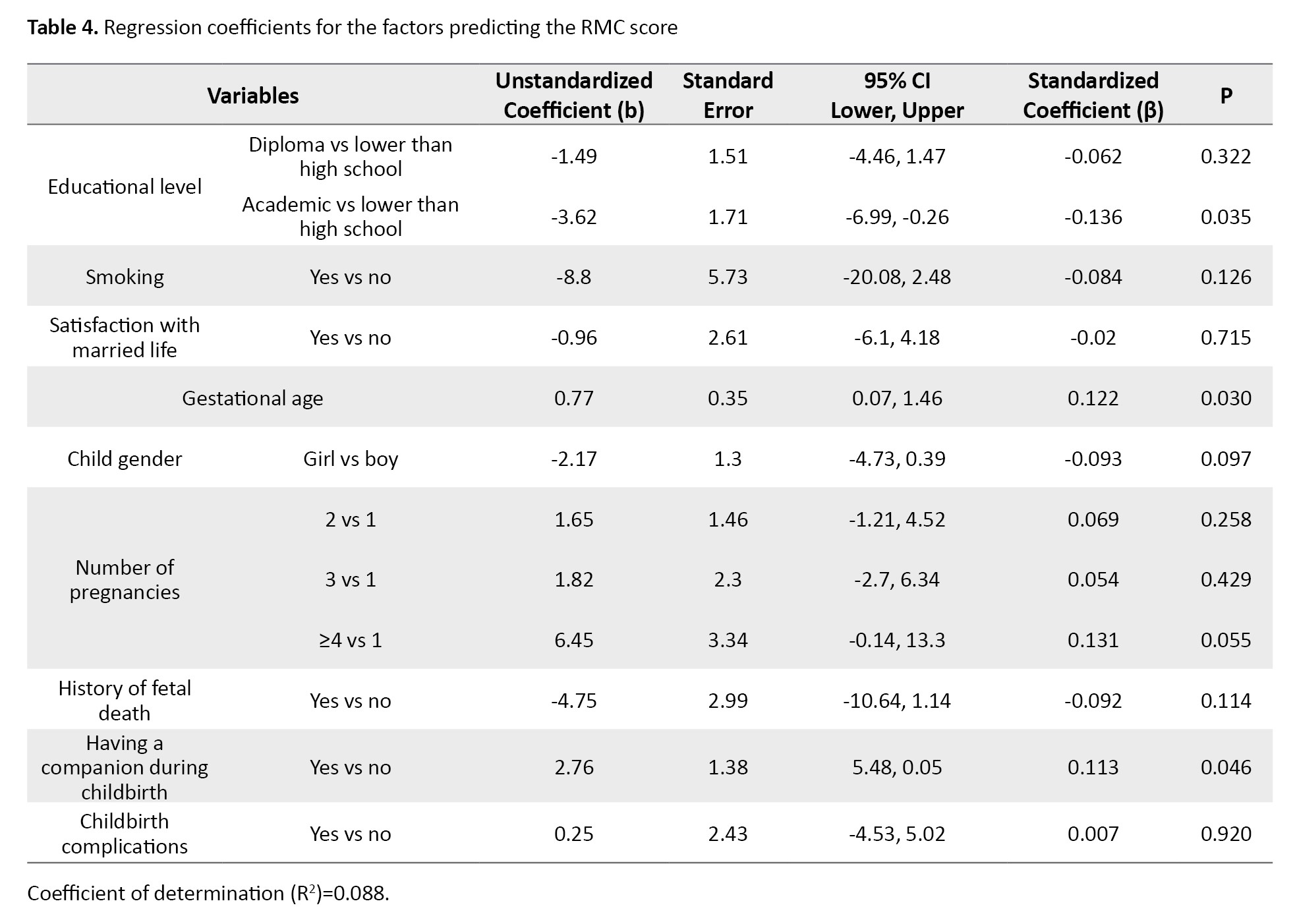

The variables with P<0.2 in the univariate analysis (Table 3) were entered into the multivariate regression model.

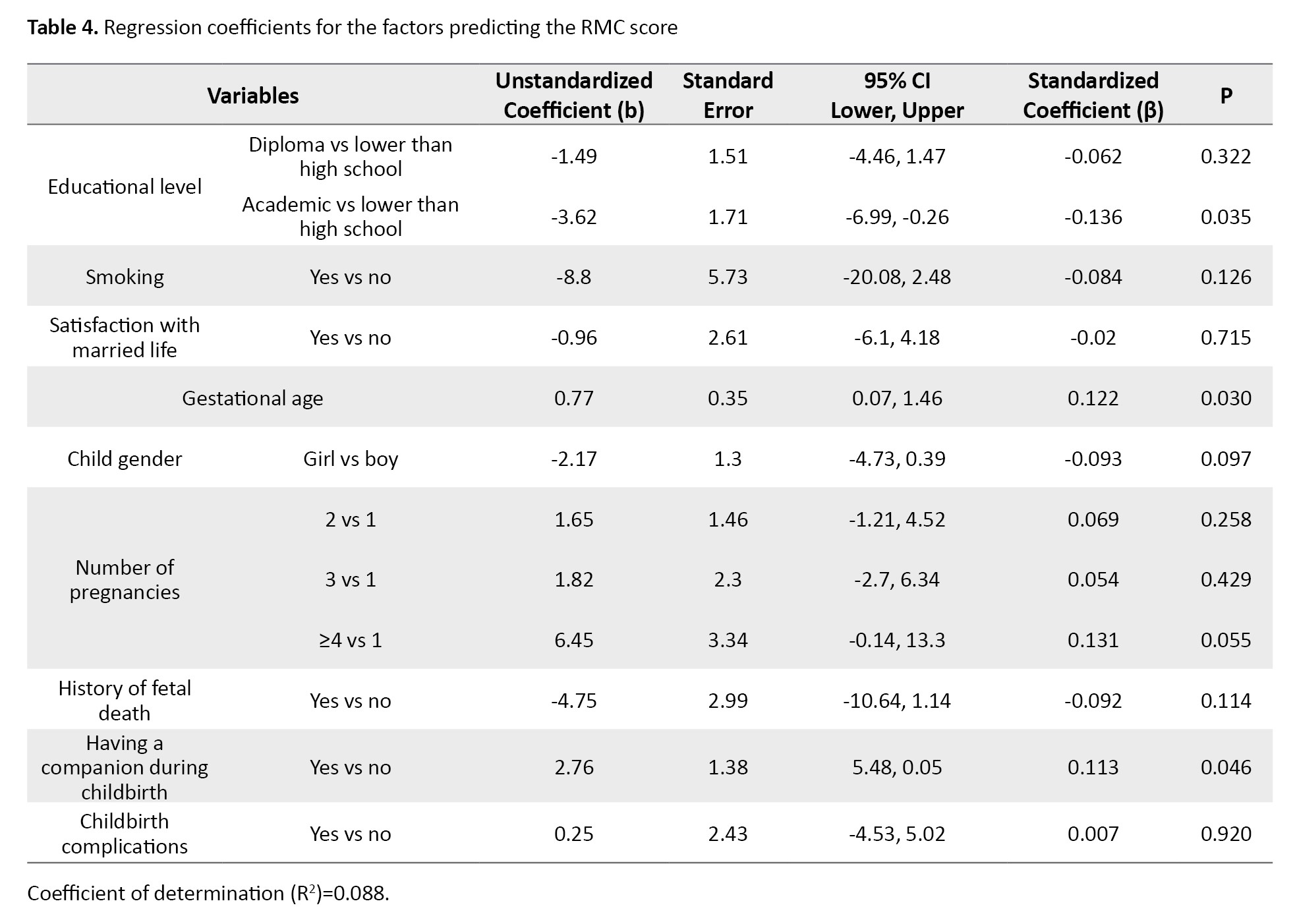

Based on the regression coefficients, the RMC score of women with an academic education was significantly 3.62 units lower than that of women with lower than high school education (b=-3.62, 95% CI; -6.99%, 0.26%, P=0.035). For every one-week increase in gestational age, the RMC score increased by 0.77 units (b=0.77, 95% CI; 0.07%, 1.46%, P=0.030). The RMC score in women with a companion during birth was significantly higher than that of those without a companion by 2.76 units (b=2.76, 95% CI; 0.05%, 5.48%, P=0.046). The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.088, indicating that 8.8% of the variation in the RMC score is explained by the factors mentioned (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, more than half of the women reported receiving respectful care, which is higher than in other similar studies [2, 18, 24]. The higher RMC level in our study may be due to the adoption of recent health and treatment policies and the implementation of the “Mother-Friendly Hospital” plan in Iran, which requires healthcare providers to pay closer attention to Providing high-quality maternal services. One component of the “Mother-Friendly Hospital” plan is to respect mothers’ rights, preserve their self-esteem, and ensure their autonomy. Observing these principles can improve the RMC level [25, 26]. The level of RMC in our study was lower than that in other studies [27-29]. This discrepancy can be attributed to differences in the number of women, sampling methods, tools used, and the culture and socio-economic status of women.

In this study, the highest score was in the domain of abuse-free care, which is consistent with the results of Sethi et al. [30]. Contrary to our results, Yosef et al. [31] reported that abuse-free care had the lowest score. This discrepancy may be due to differences in sample size, inclusion criteria, and demographic characteristics. The need to improve RMC has been emphasized in Iran through training workshops for midwives to enhance their knowledge and practice [32]. It can be one of the reasons for the high level of abuse-free care in our study. In the present study, the lowest score was in the domain of timely care, which includes items related to delays in care or keeping mothers waiting. This result is consistent with the findings of other studies [24, 33, 34]. However, according to the WHO, timely care is one of the standards for achieving high-quality RMC, such that maternal and neonatal outcomes can be improved through it [35].

We found a significant difference in the total RMC score based on maternal education and the presence of a companion during birth, and the gestational age had a significant relationship with the total RMC score. The score of RMC in mothers with an academic education was significantly lower than that in women with lower than high school education. This is in line with the results of other studies [6, 36-38]. A reduction in the RMC score with increasing women’s educational level may be because higher educational attainment raises expectations for service quality. Additionally, women with higher levels of education are more aware of their rights and have a greater capacity to report disrespectful behavior. The results are not consistent with the results of some studies [39, 40]. The possible reason may be differences in the tools used, the number of samples, the sampling method, and environmental and socio-economic factors. In the present study, the RMC score among women with a companion during childbirth was significantly higher than among those without a companion. This result is consistent with findings from similar studies [41-43]. The presence of a companion can reduce the anxiety, fear, and perceived pain of childbirth through emotional support and improve the labor experience [41, 44]. In the study by Mirzania et al. [45], the presence of a companion was associated with increased reports of disrespectful behaviors, attributed to limited knowledge of the childbirth process in the woman and her companion. In the present study, higher gestational age was associated with increased RMC score. As gestational age increases, interactions between women and healthcare providers increase, which can improve their relationships and foster trust in healthcare providers [46]. However, no significant relationship between gestational age and RMC score was found in some studies [24, 28, 47].

This study had some limitations. Since the data collection was done in the hospital, there may be a fear of reporting abusive care and a social desirability bias. Also, because the data were collected in the early postpartum period, some women were too exhausted to answer certain questions.

Based on the results, the pregnant women admitted to the postpartum department of public hospitals in Guilan Province receive a relatively high level of RMC. The effective factors are women’s educational level, the presence of a companion during birth, and gestational age. Hospitals and health centers should provide education to care providers on the rights of pregnant women and the respectful treatment they should receive, with a focus on the key factors identified in this research. More research is needed to assess the quality of RMC services in Iran.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1402.189). Written informed consent was obtained from the respondents to participate in the study.

Funding

This study was extracted from the master’s thesis of Roya Chatraei, approved by the Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design and supervision: Zahra Bostani Khalesi; Data collection: Roya Chatraei; Data analysis: Saman Maroufizadeh; Draft preparation: Roya Chatraei, Zahra Bostani Khalesi, and Mona Rahnavardi; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participating women in this study for their cooperation and time.

Pregnancy and childbirth are important events in women’s lives [1]. Access to high-quality, Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) is a basic right for women [2]. Over the last few decades, this accessibility has encouraged women to give birth in hospitals [3]. Achieving the sustainable development goals of reducing maternal mortality to less than 70 per 100,000 births and reducing infant mortality to less than 12 per 1,000 live births by 2030 requires providing safe and high-quality RMC to mothers. Despite the emphasis, considerable progress has not been made toward these goals due to inadequate adherence to aspects of RMC [4]. Women still experience disrespect and abuse during labor and birth [5]. The prevalence of this disrespect and abuse has been reported to be 36.3% in the Netherlands [6], 77.6% in Germany [7], 17.3% in America [8], 71% in India [9], and 75.7% in Iran [10].

Lack of observing the principles of high-quality RMC and existence of physical or verbal abuse, discrimination, vaginal examinations without permission, or procedures such as episiotomy and induction of labor can lead to a sense of worthlessness, induces weakness to the woman, and causes an increase in negative and maternal and neonatal outcomes [3], including postpartum depression [11], reduced desire for subsequent pregnancies, and increased intervals between pregnancies [1]. Generally, owing to the extensive negative outcomes of failing to provide RMC, active organizations in the health sector emphasized this aspect of maternity care as one of the most significant factors in high-quality, standard care and proposed it as an objective and measurable quality of maternal and neonatal care [12].

Very limited studies had been conducted in the area of abuse and disrespect towards women in maternity centers in previous decades. Bowser and Hill called for collective action on this issue, which led to greater attention to the mother’s experiences during childbirth and expanded the studies in this area [13]. After that, the White Ribbon Alliance formed a community to develop the RMC charter [14]. The World Health Organization (WHO) presented an RMC-related statement to prevent the disrespect and abuse of mothers during birth [15]. Care with respect for the dignity, privacy, and confidentiality of women provides the conditions for continuous support during labor and birth for the mother, and prevents disrespect and abuse [16].

Autonomy is also a crucial part of RMC and means a woman’s right to decide how to care for herself [17]. In this regard, an interaction between women and healthcare providers is needed [18], which can improve communication, increase the quality of maternity care, and ultimately increase women’s satisfaction with health services [19]. The satisfaction that results from increasing women’s willingness to receive health care can reduce maternal mortality and represent an effective step toward achieving the third goal of sustainable development [20]. The fear of being disrespected by healthcare providers has been mentioned as one of the reasons why many women refuse to receive services; women who experience disrespect in healthcare centers may encourage others not to use these services [21]. Given the significant role of RMC in a positive childbirth experience and the need to identify related factors to improve this experience, this study aimed to determine RMC and its associated factors among women who gave birth in hospitals of Guilan, northern Iran.

Materials and Methods

This analytical cross-sectional study was conducted on 317 women referred to the postpartum department of public hospitals in Guilan Province. As a general rule of thumb for linear regression analysis, at least 10-20 subjects are needed per independent (predictor) variable to conduct the regression analyses [22]. Therefore, the sample size was set at 315, with 15 subjects per independent variable and 21 individual, social, and fertility variables. Multi-stage, non-random sampling was used to select participants. Six hospitals were selected from the east, west, and center of Guilan Province. Sample selection was gradually conducted from each hospital based on the number of childbirths at that hospital The inclusion criteria were consent to participate in the study, normal vaginal delivery, no major abnormalities in the neonate, not taking antidepressants in the last year, not experiencing a stressful event (such as divorce, death of first-degree relatives, or diagnosis of an incurable disease in a family member in the last three months), no mental disability, no deafness, and the ability to speak. These criteria were assessed based on the self-report. Failure to fully answer the questions in the questionnaire was considered an exclusion criterion.

The data collection tools were a questionnaire surveying sociodemographic/obstetric characteristics and the RMC questionnaire [23]. The sociodemographic characteristics included age, educational level, occupation, having a companion during childbirth, ethnicity, place of residence, and household income. The obstetric characteristics included the number of pregnancies, type of pregnancy (planned/unplanned), receiving prenatal care, length of stay in the maternity ward, number of healthcare providers during childbirth, receiving childbirth pain relief medications, the childbirth time (morning, evening, or night shift), and its agent (on-call or resident physician, midwife, midwifery student, gynecological resident). The RMC questionnaire has 15 items and 4 domains, including friendly care (7 items), abuse-free care (3 items), timely care (3 items), and discrimination-free care (2 items). In this study the items are rated as 5 (strongly agree), 4 (agree), 3 (I don’t know), 2 (disagree), and 1 (strongly disagree). The high scores indicate a more positive experience of RMC during childbirth. The scores are reported as percentages. The questionnaires were completed 6-8 hours after childbirth through interviews with the women, after explaining the study objectives to them, and ensuring the confidentiality of their information.

The qualitative variables are described as frequency (percentage), and quantitative variables are described as Mean±SD. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the data distribution. In the univariate analyses, Pearson’s correlation test, independent t-test, and one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used to investigate the relationship between RMC scores and sociodemographic/obstetric characteristics of hospitalized women. Correlation coefficient values of 0.1-0.3, 0.3-0.5, and >0.5 indicate weak, moderate, and strong correlation, respectively. In a multivariate analysis, linear regression was used to identify factors predicting RMC in hospitalized women. The data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 16, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

The mean age of women and their husbands was 28.92±5.79 and 33.03±5.63 years, respectively. The educational levels of 82 women (25.9%) and the husbands of 68 women (21.5%) were academic. Also, 22.7% of women were employed, and the husbands of 53.6% of women were self-employed. Moreover, 71% of women reported sufficient income, 84.9% were from the Guilak ethnicity, and 63.4% were living in urban areas. Other characteristics are presented in Table 1.

The mean total RMC score was 70.4±19.4, and the median score was 75 (interquartile range: 63.3-85.0). Based on these values, 75% of women reported an RMC score greater than 63.3 (Table 2).

The variables with P<0.2 in the univariate analysis (Table 3) were entered into the multivariate regression model.

Based on the regression coefficients, the RMC score of women with an academic education was significantly 3.62 units lower than that of women with lower than high school education (b=-3.62, 95% CI; -6.99%, 0.26%, P=0.035). For every one-week increase in gestational age, the RMC score increased by 0.77 units (b=0.77, 95% CI; 0.07%, 1.46%, P=0.030). The RMC score in women with a companion during birth was significantly higher than that of those without a companion by 2.76 units (b=2.76, 95% CI; 0.05%, 5.48%, P=0.046). The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.088, indicating that 8.8% of the variation in the RMC score is explained by the factors mentioned (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, more than half of the women reported receiving respectful care, which is higher than in other similar studies [2, 18, 24]. The higher RMC level in our study may be due to the adoption of recent health and treatment policies and the implementation of the “Mother-Friendly Hospital” plan in Iran, which requires healthcare providers to pay closer attention to Providing high-quality maternal services. One component of the “Mother-Friendly Hospital” plan is to respect mothers’ rights, preserve their self-esteem, and ensure their autonomy. Observing these principles can improve the RMC level [25, 26]. The level of RMC in our study was lower than that in other studies [27-29]. This discrepancy can be attributed to differences in the number of women, sampling methods, tools used, and the culture and socio-economic status of women.

In this study, the highest score was in the domain of abuse-free care, which is consistent with the results of Sethi et al. [30]. Contrary to our results, Yosef et al. [31] reported that abuse-free care had the lowest score. This discrepancy may be due to differences in sample size, inclusion criteria, and demographic characteristics. The need to improve RMC has been emphasized in Iran through training workshops for midwives to enhance their knowledge and practice [32]. It can be one of the reasons for the high level of abuse-free care in our study. In the present study, the lowest score was in the domain of timely care, which includes items related to delays in care or keeping mothers waiting. This result is consistent with the findings of other studies [24, 33, 34]. However, according to the WHO, timely care is one of the standards for achieving high-quality RMC, such that maternal and neonatal outcomes can be improved through it [35].

We found a significant difference in the total RMC score based on maternal education and the presence of a companion during birth, and the gestational age had a significant relationship with the total RMC score. The score of RMC in mothers with an academic education was significantly lower than that in women with lower than high school education. This is in line with the results of other studies [6, 36-38]. A reduction in the RMC score with increasing women’s educational level may be because higher educational attainment raises expectations for service quality. Additionally, women with higher levels of education are more aware of their rights and have a greater capacity to report disrespectful behavior. The results are not consistent with the results of some studies [39, 40]. The possible reason may be differences in the tools used, the number of samples, the sampling method, and environmental and socio-economic factors. In the present study, the RMC score among women with a companion during childbirth was significantly higher than among those without a companion. This result is consistent with findings from similar studies [41-43]. The presence of a companion can reduce the anxiety, fear, and perceived pain of childbirth through emotional support and improve the labor experience [41, 44]. In the study by Mirzania et al. [45], the presence of a companion was associated with increased reports of disrespectful behaviors, attributed to limited knowledge of the childbirth process in the woman and her companion. In the present study, higher gestational age was associated with increased RMC score. As gestational age increases, interactions between women and healthcare providers increase, which can improve their relationships and foster trust in healthcare providers [46]. However, no significant relationship between gestational age and RMC score was found in some studies [24, 28, 47].

This study had some limitations. Since the data collection was done in the hospital, there may be a fear of reporting abusive care and a social desirability bias. Also, because the data were collected in the early postpartum period, some women were too exhausted to answer certain questions.

Based on the results, the pregnant women admitted to the postpartum department of public hospitals in Guilan Province receive a relatively high level of RMC. The effective factors are women’s educational level, the presence of a companion during birth, and gestational age. Hospitals and health centers should provide education to care providers on the rights of pregnant women and the respectful treatment they should receive, with a focus on the key factors identified in this research. More research is needed to assess the quality of RMC services in Iran.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1402.189). Written informed consent was obtained from the respondents to participate in the study.

Funding

This study was extracted from the master’s thesis of Roya Chatraei, approved by the Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design and supervision: Zahra Bostani Khalesi; Data collection: Roya Chatraei; Data analysis: Saman Maroufizadeh; Draft preparation: Roya Chatraei, Zahra Bostani Khalesi, and Mona Rahnavardi; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participating women in this study for their cooperation and time.

References

- Hosseini Tabaghdehi M, Kolahdozan S, Keramat A, Shahhossein Z, Moosazadeh M, Motaghi Z. Prevalence and factors affecting the negative childbirth experiences: A systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020; 33(22):3849-56. [DOI:10.1080/14767058.2019.1583740] [PMID]

- Hughes CS, Kamanga M, Jenny A, Zieman B, Warren C, Walker D, et al. Perceptions and predictors of respectful maternity care in Malawi: A quantitative cross-sectional analysis. Midwifery. 2022; 112:103403. [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2022.103403] [PMID]

- Bohren MA, Tunçalp Ö, Miller S. Transforming intrapartum care: Respectful maternity care. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020; 67:113-26. [DOI:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.02.005] [PMID]

- Ige WB, Cele WB. Barriers to the provision of respectful maternity care during childbirth by midwives in South-West, Nigeria: Findings from semi-structured interviews with midwives. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2022; 17:10044. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijans.2022.100449]

- Sheferaw ED, Mengesha TZ, Wase SB. Development of a tool to measure women’s perception of respectful maternity care in public health facilities. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016; 16:67. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-016-0848-5] [PMID]

- Van der Pijl MSG, Verhoeven CJM, Verweij R, van der Linden T, Kingma E, Hollander MH, et al. Disrespect and abuse during labour and birth amongst 12,239 women in the Netherlands: A national survey. Reprod Health. 2022; 19(1):160. [DOI:10.1186/s12978-022-01460-4] [PMID]

- Limmer C, Stoll K, Vedam S, Leinweber J, Gross MM. Measuring disrespect and abuse during childbirth in a high-resource country: Development and validation of a German self-report tool. Midwifery. 2023; 126:103809. [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2023.103809] [PMID]

- Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, Rubashkin N, Cheyney M, Strauss N, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019; 16(1):77. [DOI:10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2] [PMID]

- Ansari H, Yeravdekar R. Respectful maternity care during childbirth in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Postgrad Med. 2020; 66(3):133-40. [DOI:10.4103/jpgm.JPGM_648_19] [PMID]

- Hajizadeh K, Vaezi M, Meedya S, Mohammad Alizadeh Charandabi S, Mirghafourvand M. Prevalence and predictors of perceived disrespectful maternity care in postpartum Iranian women: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20(1):463. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-03124-2] [PMID]

- Martins ACM, Giugliani ERJ, Nunes LN, Bizon AMBL, de Senna AFK, Paiz JC, et al. Factors associated with a positive childbirth experience in Brazilian women: A cross-sectional study. Women Birth. 2021; 34(4):e337-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.wombi.2020.06.003] [PMID]

- Wilson-Mitchell K, Robinson J, Sharpe M. Teaching respectful maternity care using an intellectual partnership model in Tanzania. Midwifery. 2018; 60:27-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2018.01.019] [PMID]

- Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth: Report of a landscape analysis. USAID-TRAction Project. Boston: Harvard School of Public Health University Research; 2010. [Link]

- Collins B, Hall J, Hundley V, Ireland J. Effective communication: Core to promoting respectful maternity care for disabled women. Midwifery. 2023; 116:103525. [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2022.103525] [PMID]

- Ministry of Public Health of Afghanistan. Respectful maternity care orientation pacage. Kabol: Unsafe. 2017. [Link]

- Reingold RB, Barbosa I, Mishori R. Respectful maternity care in the context of COVID-19: A human rights perspective. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020; 151(3):319-21. [DOI:10.1002/ijgo.13376] [PMID]

- Feijen-de Jong EI, van der Pijl M, Vedam S, Jansen DEMC, Peters LL. Measuring respect and autonomy in Dutch maternity care: Applicability of two measures. Women Birth. 2020; 33(5):e447-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.wombi.2019.10.008] [PMID]

- Bante A, Teji K, Seyoum B, Mersha A. Respectful maternity care and associated factors among women who delivered at Harar hospitals, eastern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20(1):86. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-2757-x] [PMID]

- Mohammadi F, Tabatabaei HS, Mozafari F, Gillespie M. Caregivers’ perception of women’s dignity in the delivery room: A qualitative study. Nurs Ethics. 2020; 27(1):116-26.[DOI:10.1177/0969733019834975] [PMID]

- Moridi M, Pazandeh F, Potrata B. Midwives’ knowledge and practice of respectful maternity care: A survey from Iran. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022; 22(1):752. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-022-05065-4] [PMID]

- Jiru HD, Sendo EG. Promoting compassionate and respectful maternity care during facility-based delivery in Ethiopia: Perspectives of clients and midwives. BMJ Open. 2021; 11(10):e051220. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051220] [PMID]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. London: Pearson; 2007. [Link]

- Taavoni S, Goldani Z, Rostami Gooran N, Haghani H. Development and assessment of respectful maternity care questionnaire in Iran. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2018; 6(4):334-49. [PMID]

- Hajizadeh K, Vaezi M, Meedya S, Mohammad Alizadeh Charandabi S, Mirghafourvand M. Respectful maternity care and its relationship with childbirth experience in Iranian women: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20(1):468. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-03118-0] [PMID]

- Abbasi Khameneh F, Riahi L. [The relationship between clinical leadership competencies of midwives employed in public hospitals of Iran university of medical sciences with mother friendly hospitals indicators (Persian)]. Teb VA Tazkiyeh. 2018; 26(4):323-32. [Link]

- Ministry of Health and Medical Education. [National guide to providing midwifery and delivery services in mother-friendly hospitals (Persian)]. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2006. [Link]

- Adugna A, Kindie K, Abebe GF. Respectful maternity care and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in three hospitals of Southwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2023; 10:1055898. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1055898] [PMID]

- Esan OT, Maswime S, Blaauw D. Directly observed and reported respectful maternity care received during childbirth in public health facilities, Ibadan Metropolis, Nigeria. PLoS One. 2022; 17(10):e0276346. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0276346] [PMID]

- Pathak P, Ghimire B. Perception of women regarding respectful maternity care during facility-based childbirth. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2020; 2020:5142398. [DOI:10.1155/2020/5142398] [PMID]

- Sethi R, Gupta S, Oseni L, Mtimuni A, Rashidi T, Kachale F. The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based maternity care in Malawi: Evidence from direct observations of labor and delivery. Reprod Health. 2017; 14(1):111. [DOI:10.1186/s12978-017-0370-x] [PMID]

- Yosef A, Kebede A, Worku N. Respectful maternity care and associated factors among women who attended delivery services in referral hospitals in northwest Amhara, Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020; 13:1965-73. [DOI:10.2147/JMDH.S286458] [PMID]

- Abdollahpour S, Bayrami R, Ghasem Zadeh N, Alinezhad V. [Investigating the effect of implementation of respecting pregnant women training workshop on knowledge and performance of medwives (Persian)]. Nurs Midwifery J. 2023; 21(4):334-42. [DOI:10.61186/unmf.21.4.334]

- Mousa O, Turingan O. Quality of care in the delivery room: Focusing on respectful maternal care practices. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2018; 9(1):1-5. [DOI:10.5430/jnep.v9n1p1]

- Rosen HE, Lynam PF, Carr C, Reis V, Ricca J, Bazant ES, et al. Direct observation of respectful maternity care in five countries: A cross-sectional study of health facilities in East and Southern Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015; 15:306. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-015-0728-4] [PMID]

- WHO. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. Geneva: WHO; 2016. [Link]

- Kruk ME, Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, Ramsey K, Moyo W, Freedman LP. Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: A facility and community survey. Health Policy Plan. 2018; 33(1):e26-e33. [DOI:10.1093/heapol/czu079] [PMID]

- Leite TH, Pereira APE, Leal MDC, da Silva AAM. Disrespect and abuse towards women during childbirth and postpartum depression: Findings from birth in Brazil study. J Affect Disord. 2020; 273:391-401. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.052] [PMID]

- Siraj A, Teka W, Hebo H. Prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility based child birth and associated factors, Jimma University Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019; 19(1):185.[DOI:10.1186/s12884-019-2332-5] [PMID]

- Ferede WY, Gudayu TW, Gessesse DN, Erega BB. Respectful maternity care and associated factors among mothers who gave birth at public health institutions in South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia 2021. Womens Health (Lond). 2022; 18:17455057221116505. [DOI:10.1177/17455057221116505] [PMID]

- Adane D, Bante A, Wassihun B. Respectful focused antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women who visit Shashemene town public hospitals, Oromia region, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2021; 21(1):92.[DOI:10.1186/s12905-021-01237-0] [PMID]

- Seth I, Sunayana, Singhal S, Seth A, Garg A. The impact of birth companion on respectful maternity care and labor outcomes among Indian women: A prospective comparative study. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2023; 12:3508-14. [DOI:10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20233626]

- Gebremichael MW, Worku A, Medhanyie AA, Berhane Y. Mothers’ experience of disrespect and abuse during maternity care in northern Ethiopia. Glob Health Action. 2018; 11(sup3):1465215. [DOI:10.1080/16549716.2018.1465215] [PMID]

- Maldie M, Egata G, Chanie MG, Muche A, Dewau R, Worku N, et al. Magnitude and associated factors of disrespect and abusive care among laboring mothers at public health facilities in Borena District, South Wollo, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2021; 16(11):e0256951. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0256951] [PMID]

- Wahdan Y, Abu-Rmeileh NME. The association between labor companionship and obstetric violence during childbirth in health facilities in five facilities in the occupied Palestinian territory. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023; 23(1):566. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-023-05811-2] [PMID]

- Mirzania M, Shakibazadeh E, Bohren MA, Hantoushzadeh S, Babaey F, Khajavi A, et al. Mistreatment of women during childbirth and its influencing factors in public maternity hospitals in Tehran, Iran: A multi-stakeholder qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2023; 20(1):79. [DOI:10.1186/s12978-023-01620-0] [PMID]

- Nicoloro-SantaBarbara J, Rosenthal L, Auerbach MV, Kocis C, Busso C, Lobel M. Patient-provider communication, maternal anxiety, and self-care in pregnancy. Soc Sci Med. 2017; 190:133-40. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.011] [PMID]

- Dornelas ACVR, Rodrigues LDS, Penteado MP, Batista RFL, Bettiol H, Cavalli RC, et al. Abuse, disrespect and mistreatment during childbirth care: Contribution of the Ribeirão Preto cohorts, Brazil. Cien Saude Colet. 2022; 27(2):535-44. [DOI:10.1590/1413-81232022272.01672021] [PMID]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2025/01/19 | Accepted: 2025/05/25 | Published: 2026/01/11

Received: 2025/01/19 | Accepted: 2025/05/25 | Published: 2026/01/11

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |