Mon, Dec 29, 2025

Volume 35, Issue 3 (6-2025)

JHNM 2025, 35(3): 188-199 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

bazzi A, Pouralizadeh M, ebadi A, Kazemnezhadleyli E. Educational Leadership Styles of Nursing Educators in Clinical Practice: A Qualitative Content Analysis. JHNM 2025; 35 (3) :188-199

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2471-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2471-en.html

1- PhD. Candidate, Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Associate Professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,pouralizadehm@gmail.com

3- Professor, Nursing Care Research Center, Clinical Sciences Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Associate Professor, Department of Biostatistics, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Associate Professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,

3- Professor, Nursing Care Research Center, Clinical Sciences Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Associate Professor, Department of Biostatistics, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 579 kb]

(363 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (628 Views)

Full-Text: (228 Views)

Introduction

Effective leadership in nursing education is critical for fostering student engagement, clinical competence, and evidence-based curricula [1-3]. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated transformative shifts in clinical education, including rapid adoption of virtual technologies (e.g. simulation, virtual reality) and evolving student expectations shaped by digital and social media [4]. While nursing leaders are accustomed to change, these developments demand unprecedented adaptability in pedagogical strategies and leadership styles [5]. Current research emphasizes clinical skill development but overlooks nursing educators model leadership in academic settings [6]. This gap hinders the preparation of future nurse leaders capable of navigating complex and technology-driven healthcare environments. Furthermore, faculty evaluations often informed by student feedback rarely assess leadership approaches, despite their impact on teaching quality and educational outcomes [7, 8].

While quantitative studies on leadership styles prioritize measurable behaviors (e.g. feedback frequency) [9] and identify correlations (e.g. transformational leadership and student satisfaction) [10], they inadequately explain how trust is cultivated or why hierarchical methods conflict with digitally native learners’ expectations [11]. This qualitative study addresses these gaps by synthesizing faculty and student perspectives, revealing leadership as co-constructed through interactions. Faculty narratives expose intentional strategies (e.g. balancing safety and autonomy), while student accounts highlight perceived impacts (e.g. empowerment vs humiliation), offering a holistic view of leadership dynamics [12]. Involving both groups captures the bidirectional nature of educational relationships, aligning educators’ intentions with learners’ experiences [13]. This study aimed to explore the educational leadership styles exhibited by clinical nursing faculties in clinical practice settings.

Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative research design with a conventional content analysis approach, allowing categories and themes to emerge directly from the data. This methodology ensures that the findings are rooted in participants’ experiences and perspectives without relying on pre-established frameworks [13, 14].

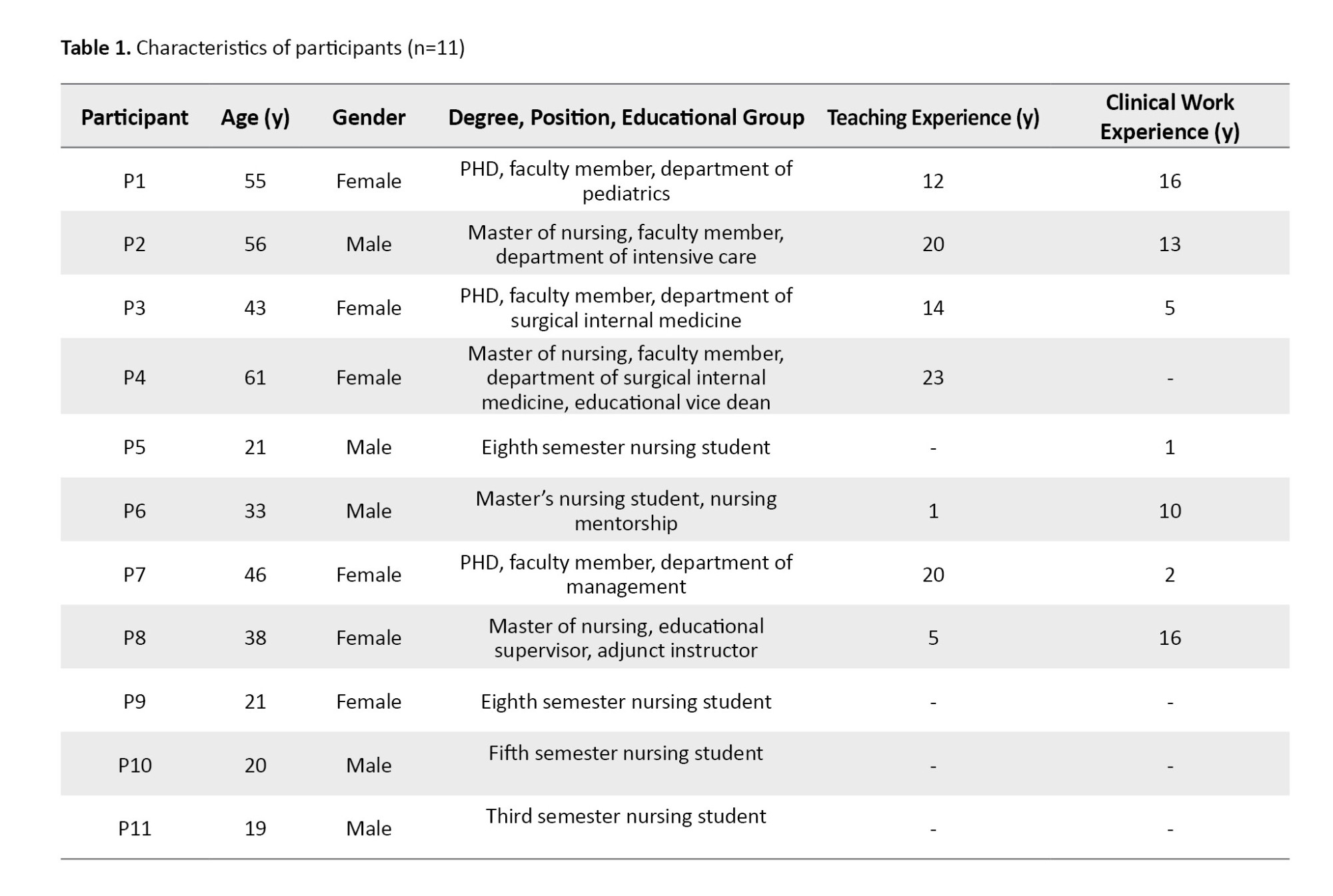

The study included 11 participants, comprising academic and non-academic faculty, educational staff, undergraduate and graduate nursing students, educational supervisors, and deputies. Purposive sampling was used to ensure diversity in age, gender, educational background, work experience, and academic standing, thereby capturing various perspectives on educational leadership in clinical nursing practice.

Participants were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: Experience in educational or clinical nursing activities, a willingness to participate in the study, and the ability to communicate their experiences and perspectives effectively. Individuals were excluded if they lacked direct experience in clinical or educational nursing roles, declined to provide informed consent, had language barriers or scheduling conflicts preventing full participation in interviews, and were currently or recently (within the past six months) in similar studies to avoid response bias. Data collection was primarily done through semi-structured interviews, supplemented by observations and field notes. The analysis followed the conventional content analysis approach, including coding, categorization, theme extraction, and final interpretation.

Interviews were conducted in private, quiet settings within the nursing school or affiliated hospitals, including offices, educational rooms (e.g. classrooms or workshops), and conference rooms. Each interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim. Broad, open-ended questions were initially posed to encourage openness, with more specific questions based on participants’ responses. The interviews began with the broad, open-ended prompt: “Can you share your experiences regarding the leadership styles of nursing educators in clinical practice?” Exploratory prompts such as “Can you elaborate?” or “Could you provide an example?” were used when needed. Participants were encouraged to share experiences related to challenging situations, conflicts, student feedback, and behaviors aimed at achieving educational goals. Techniques like silence, echoing statements, and verbal affirmations facilitated the process.

The final interview questions were developed with input from the research team and a review of relevant qualitative studies. Data collection continued until saturation was reached, meaning no new themes emerged. Interviews typically lasted 40-55 minutes. Transcripts were reviewed multiple times and analyzed following Graneheim and Lundman’s method, which involves transcribing interviews, extracting meaningful essences, labeling them as semantic units, categorizing them, and assigning abstract titles known as codes to create main categories [15]. The study was done during July to October 2024.

To ensure credibility and trustworthiness, several strategies were employed. Member checking was implemented, where participants reviewed preliminary findings for accuracy. Data triangulation was used by incorporating interviews, observations, and field notes, strengthening the consistency and depth of the findings. Peer review by qualitative research experts validated the methodology, ensuring adherence to standards. The data collection and analysis process were meticulously documented, maintaining an audit trail for transparency and verification of decisions. These strategies enhanced the reliability, validity, and depth of the study, providing a nuanced understanding of educational leadership in clinical nursing practice [16]. Data analyses was done by MAXQDA software, version 2020.

Results

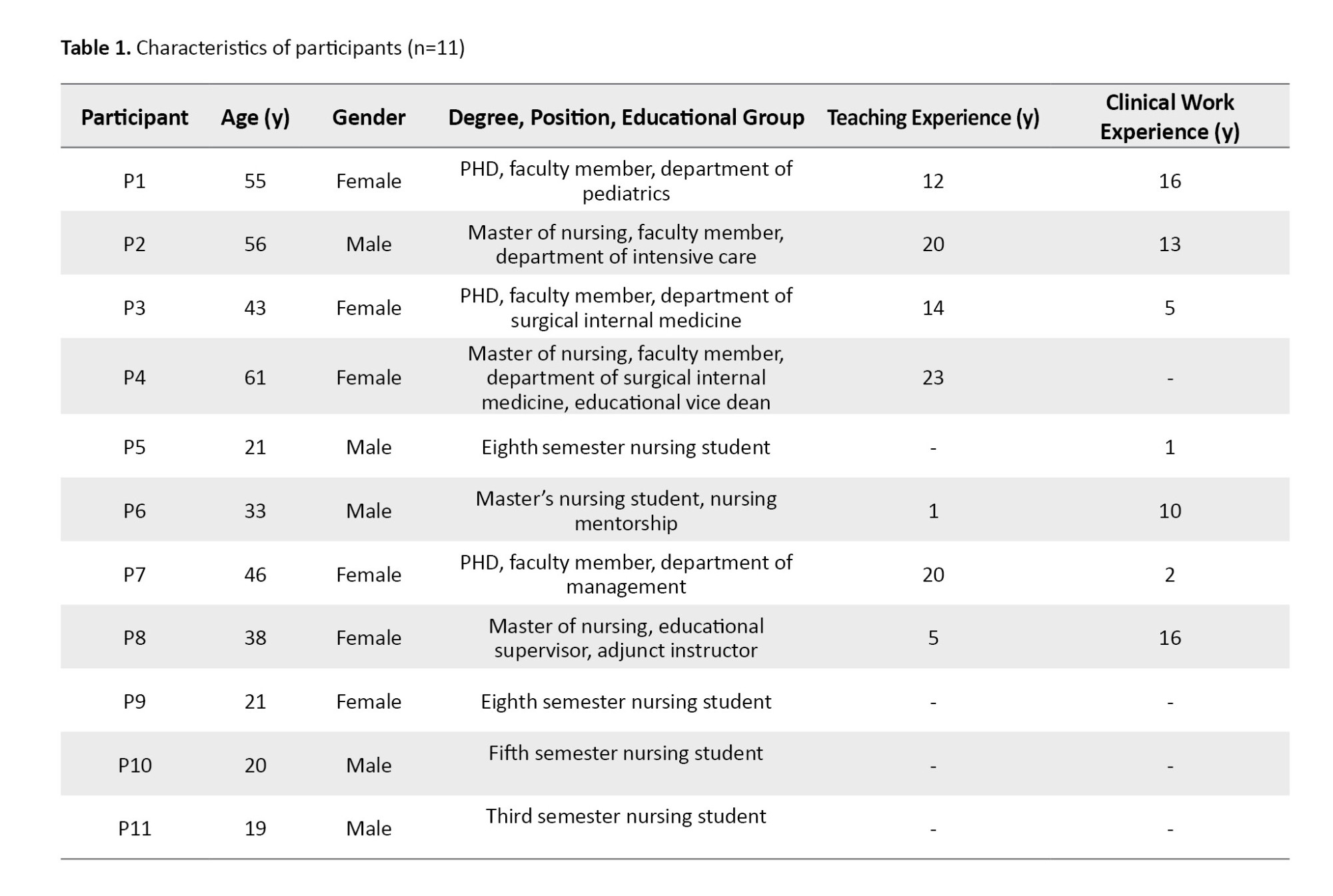

Data saturation was achieved with 11 participants (5 men and 6 women; mean age: 37.54 3.5 years). Participants included nursing faculties, educational supervisors, and undergraduate/graduate students with diverse clinical experience and academic roles. Additional participant characteristics, including work experience, position, and academic department, are presented in Table 1.

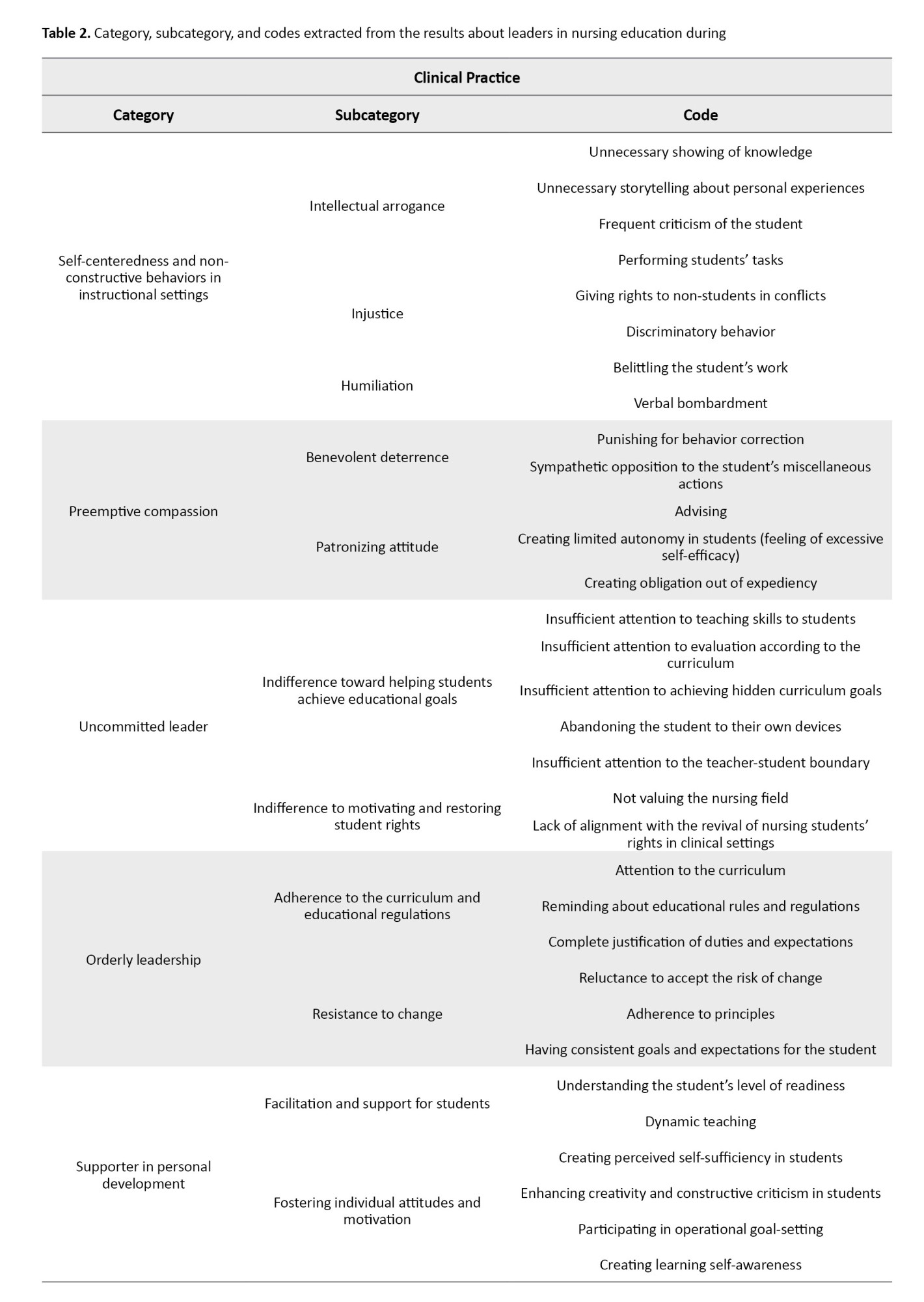

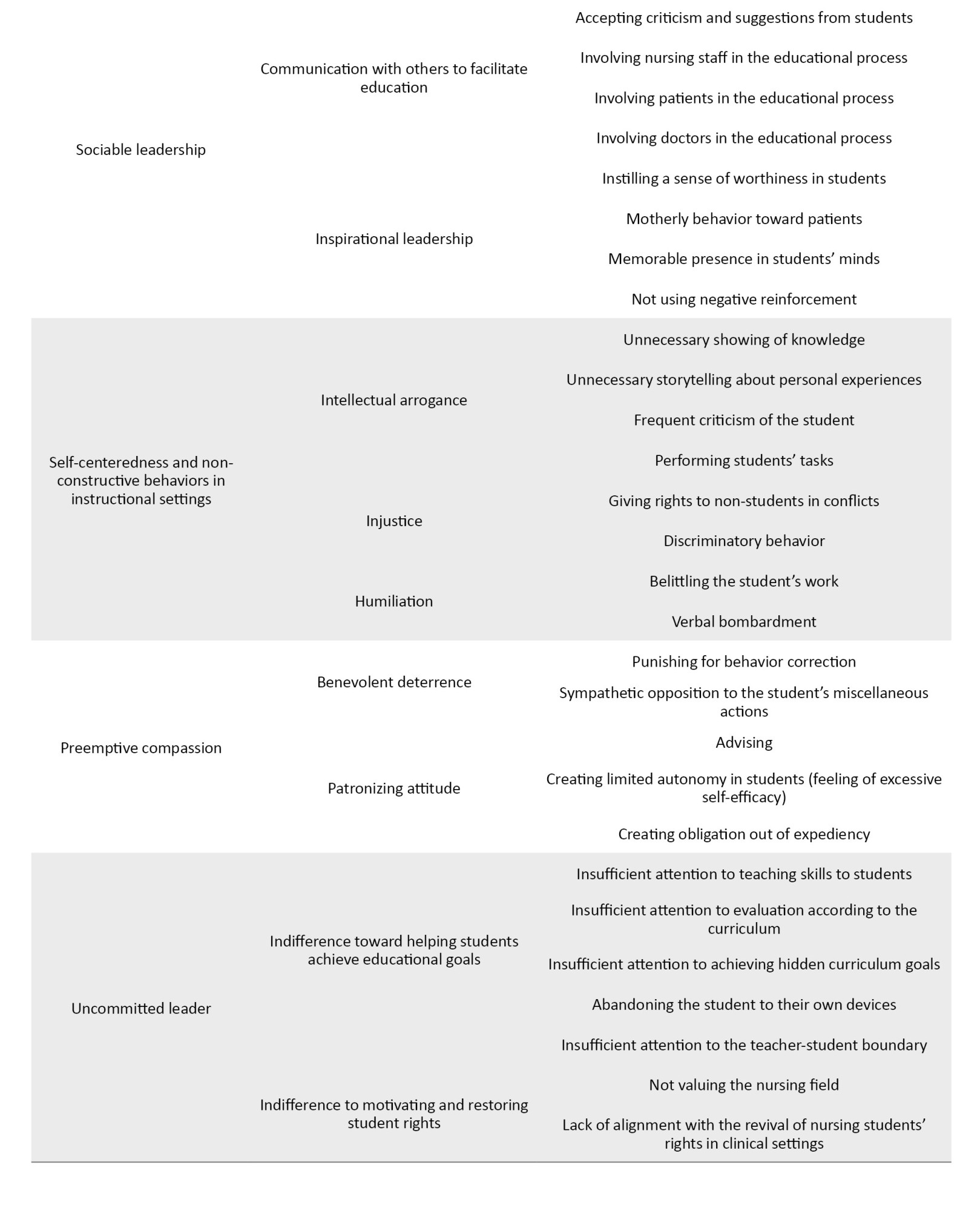

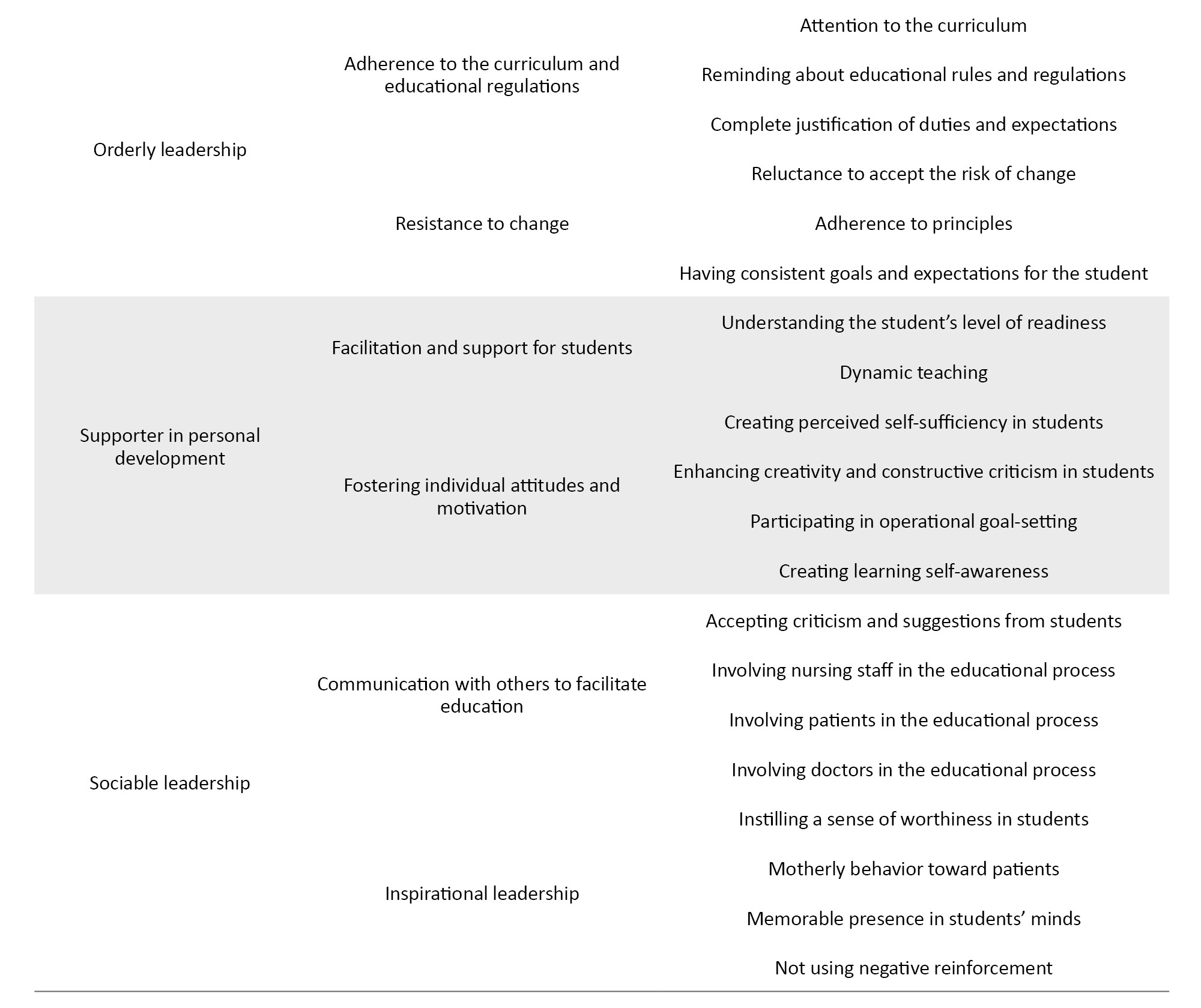

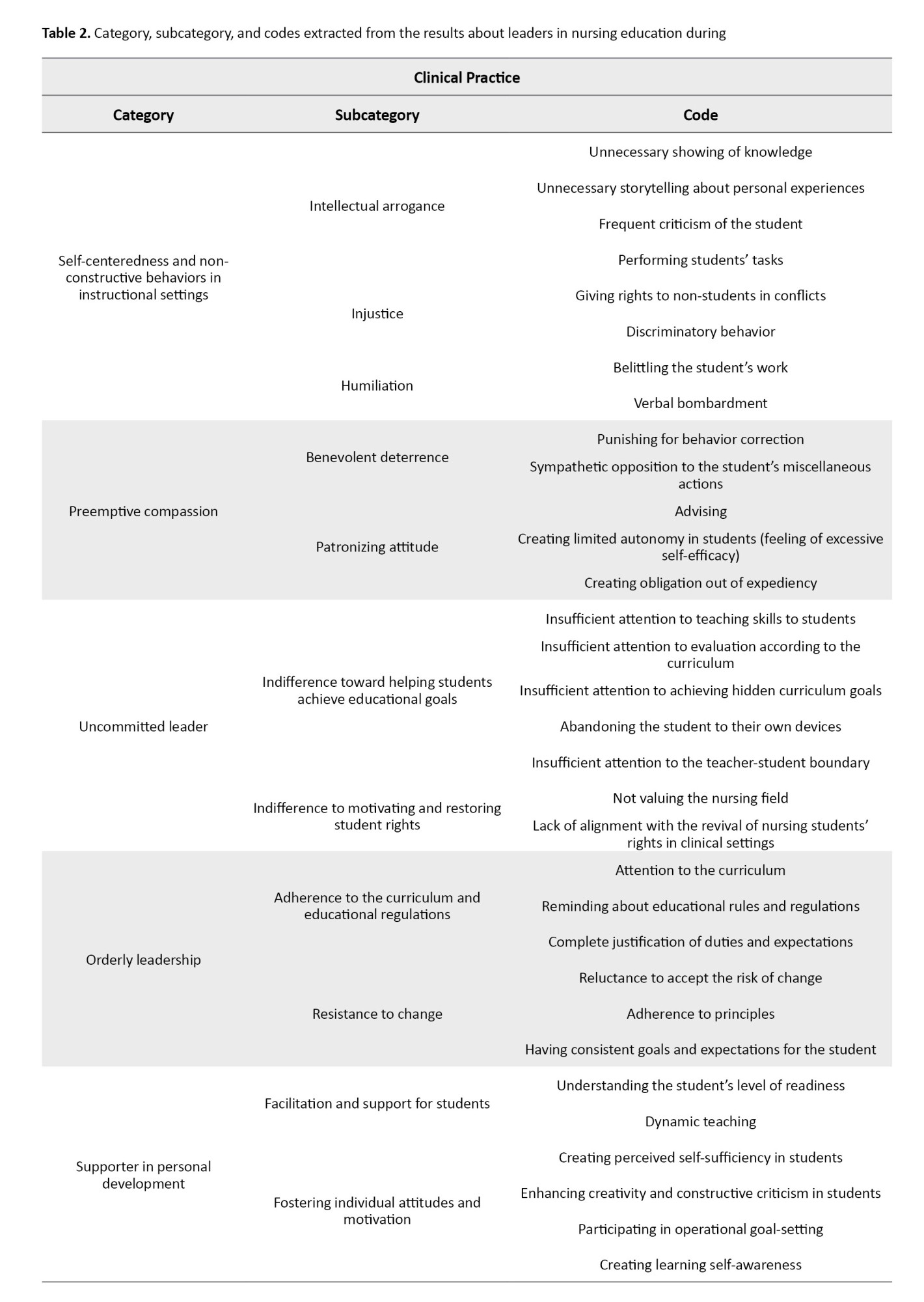

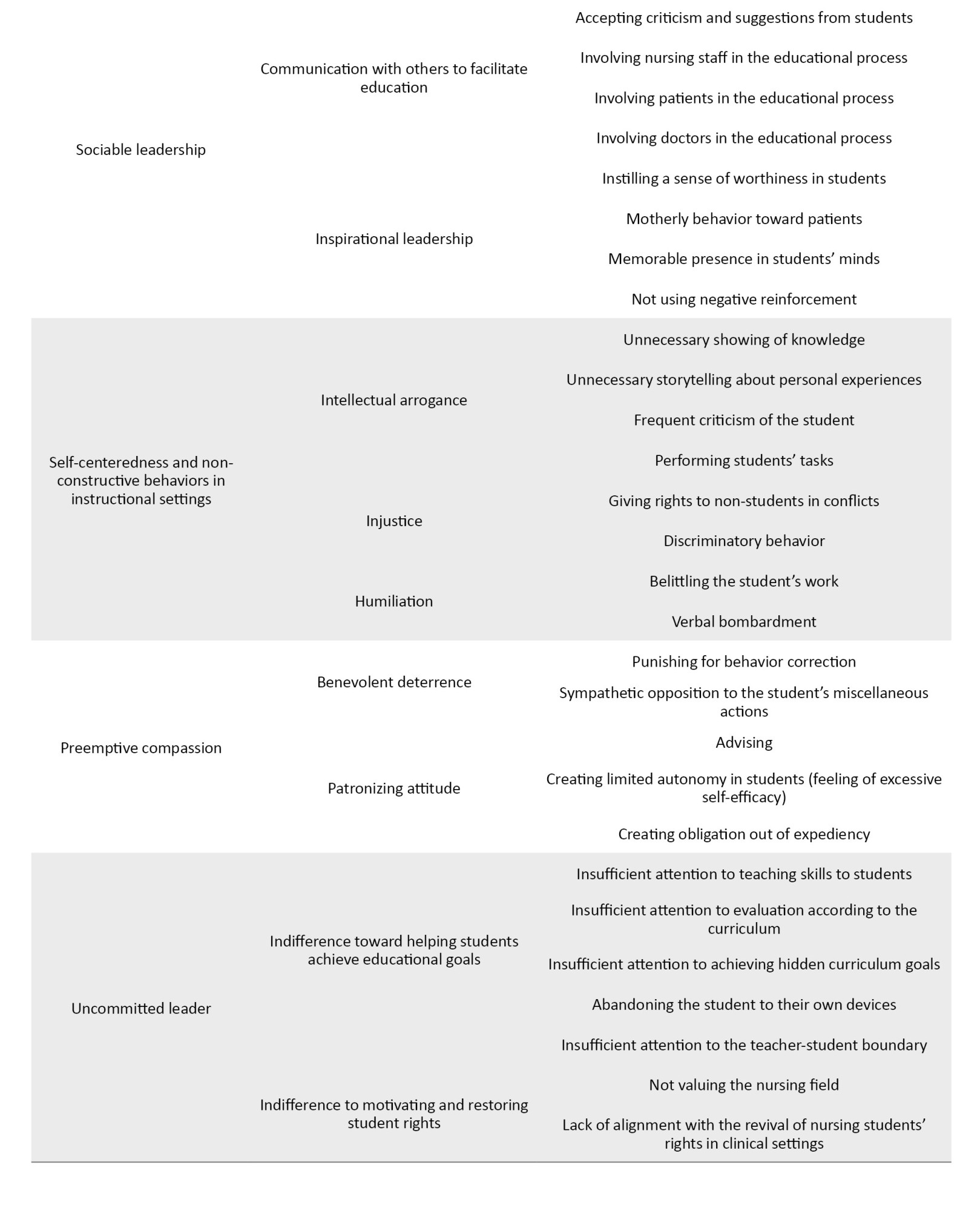

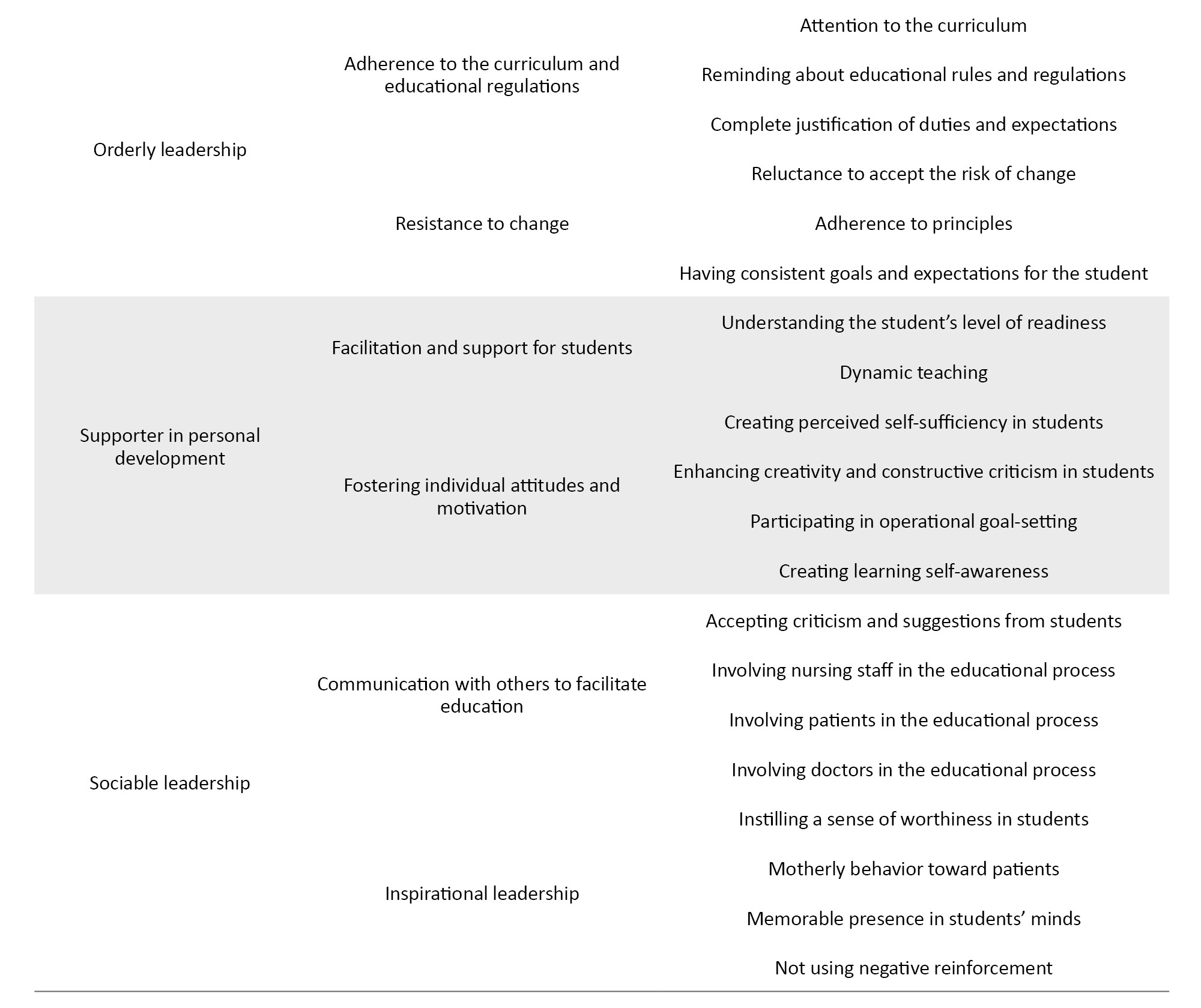

In the initial refinement from the content analysis during fieldwork, 366 codes, 35 subcategories, and 15 categories were extracted. The final refinement from interviews with participants and field notes resulted in the extraction of 6 categories, 13 subcategories, and 40 codes. The main categories included self-centered and non-constructive, preemptive compassion, uncommitted leadership, orderly leadership, supporter in personal development, and sociable leadership (Table 2). The participants’ experiences regarding the extracted codes were categorized separately.

Self-centeredness and non-constructive behaviors” in instructional settings

This category consisted of “intellectual arrogance,” “injustice,” and “humiliation subcategories.”

Intellectual arrogance

Instructors exhibiting intellectual arrogance often prioritize self-display over effective teaching, creating a counterproductive learning environment. This issue manifests in unnecessary displays of knowledge, such as using advanced medical terminology irrelevant to the student’s current level. A participant noted, “We had an instructor who used a lot of medical terminology just to show off. These terms weren’t even related to our semester; they were for higher semesters or maybe even medical school” (participant [P]5). Similarly, one participant explained that excessive personal storytelling detracts from learning: “Instead of teaching what we needed, the instructor would go into lengthy, detailed stories about their own student experiences, which had no connection to our topic” (P11, P6). Frequent, unconstructive criticism further reinforces a hierarchical dynamic, with one student recalling how an instructor repeatedly highlighted a minor clinical error: “From the beginning of the internship until the end, always looking for faults” (P10). Additionally, some instructors undermine student autonomy by performing tasks on their behalf: “Some instructors would perform tasks that were normally our responsibility, just to show they could do them better than us” (P6) or “Instead of letting students practice simple tasks like bandaging, the instructor would do them themselves just to flaunt their skills” (P11). Such behaviors stifle learning by prioritizing the instructor's ego over student development.

Injustice

Discriminatory practices and unfair conflict resolution further erode trust in instructional relationships. Participants reported biased grading, with one stating, “We had an instructor who graded differently based on gender. Once, when grades were released, even the students were surprised and wondered why some got much higher grades” (P5). Task allocation was also inequitable, as “Some instructors would unfairly assign important practical tasks only to certain students, especially in lower semesters” (P9, P11). In conflicts, instructors often sided with senior students or staff without proper investigation: “When a conflict arose between us and a senior student, even though we were in the right, the instructor unjustly sided with the senior student. Their tone and interaction with them were different because they were also their advisor” (P5, P9).

Humiliation

Humiliating tactics, including public correction and verbal intimidation, negatively impact students’ confidence and learning. Some instructors deliberately undermined students perceived as overly confident: “If a student seemed too confident, they would bombard them with questions to put them in their place” (P2). Public shaming was common, with participants describing how “During internships, the instructor would correct our mistakes in front of patients or their families, making us feel insulted and humiliated” (P5, P11, P9). These practices damage self-esteem and discourage active participation in learning environments.

Preemptive compassion

This category consisted of benevolent deterrence and patronizing attitude subcategories.

Benevolent deterrence

Some instructors adopt a disciplinary approach rooted in preemptive compassion, enforcing strict consequences to instill professional behavior. While their intentions may be constructive, their methods sometimes feel excessively punitive. For instance, one participant described an instructor who barred a student from entering the ward for being “30 minutes late, saying, ‘They need to learn that as a nurse, they must arrive on time for shifts. Patient’s life depends on it.’ While the instructor had a point, they were overly strict, like deducting a full grade” (P6). In extreme cases, unprofessional conduct led to significant repercussions, as one participant noted: “A classmate had to repeat the internship or do an extra day with another group due to unprofessional behavior like constant tardiness and unjustified absences” (P5, P9). Though these measures aim to correct behavior, their severity may overshadow their instructive intent.

Patronizing attitude

A well-meaning yet overbearing instructional style can manifest in patronizing behaviors that limit student autonomy. Some instructors adopt an excessively advisory role, constantly reminding students to maximize their learning opportunities: “We had an instructor who would say, ‘Use your time in the ward wisely, don’t waste it on your phone.’ Their intention wasn’t to humiliate us. They genuinely cared” (P5, P9, P11). Others go further, insisting on tightly controlled experiences, as one instructor explained: “I tell students, ‘You may never experience this ward again in your life. Make the most of it.’ I insist we perform diabetic foot dressings, even if we have to coordinate with the head nurse so the intern doesn’t do it” (P4). This lack of trust often stems from past student errors, leading to hypervigilance: “Because students had made medication errors in past internships, they didn’t want the same to happen to us. They’d follow us around or double-check all medications after administration” (P11, P9, P5). Such micromanagement can stifle confidence, as one student lamented: “The instructor wouldn’t let me administer insulin alone” (P11). Another instructor defended their rigid oversight: “I show my seriousness in critical matters concerning patient safety. The student must follow my lead. They can’t act independently. I must check every task” (P3). While these actions arise from a protective instinct, they risk fostering dependency rather than competence.

Uncommitted leadership

The “uncommitted leadership” was another category, and its subcategories consisted of “indifference towards helping students achieve educational goals” and “indifference to motivating and restoring student rights.”

Indifference towards helping students achieve educational goals

Clinical instructors demonstrating uncommitted leadership often fail to provide adequate teaching support, resulting in significant gaps in student skill development and curriculum implementation. Participants reported excessive focus on redundant theoretical content during clinical rotations, with one noting: “We had already covered this theory in previous semesters, yet we still spent excessive time on theoretical issues during internships” (P5, P6, P11). This misalignment between instruction and practical needs left students unprepared for essential assessments, as another participant explained: “For Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCEs), we encountered procedures we had barely practiced, sometimes only once or twice, because instructors prioritized conferences over hands-on training” (P5, P11).

The absence of proper supervision emerged as another critical issue. Students described being left without guidance: “Instructors would simply tell us to handle all the ward’s medications on our own, which was demoralizing without proper oversight” (P5, P9). When students sought clarification, they often received dismissive responses: “Rather than demonstrating techniques, instructors would tell us to refer back to first-semester textbooks or give vague answers like ‘Go read it yourself’” (P6, P11). Furthermore, blurring professional boundaries through excessive personal interactions, such as celebrating birthdays and exchanging gifts, created perceptions of favoritism that compromised the learning environment (field notes).

Indifference to motivating and restoring student rights

This leadership style also manifests inadequate support for students’ basic educational needs and rights. Participants highlighted systemic issues with access to learning spaces: “The conference room was restricted to interns, yet our instructors failed to advocate for our access, even when rooms sat empty” (P9, P11). The consequences were particularly frustrating during peak hours: “While medical students occupied classrooms, we were left wandering the halls searching for study space after 11 AM” (P5).

Even when opportunities existed to support students, instructors frequently acquiesced to administrative barriers without challenge. One participant recalled: “The conference rooms were completely unused during afternoon shifts, but when we tried to access them, our instructor accepted the ward manager’s refusal without question” (P6). Most concerning was instructors’ failure to intervene in student-nurse conflicts, with one admitting: “Students expected me to stand up for them in disputes with nursing staff, but I didn’t fulfill that role” (P8).

Orderly leadership

This category consisted of two subcategories: “Adherence to the curriculum and educational regulations” and “resistance to change.”

Adherence to curriculum and educational regulations

Orderly leadership is characterized by a structured, rule-based approach to teaching, emphasizing curriculum fidelity. Instructors embody this leadership style, prioritizing strict compliance with educational guidelines and ensuring teaching methods align with established standards. One participant noted, “The curriculum is my most important item. I always refer to it, even if another instructor has been teaching the same unit for 10 to 12 years. How they taught doesn’t matter. I follow the curriculum” (P1). Another participant described a colleague who exemplified this approach: “One instructor I worked with strictly followed the rules. Lesson plans, grading, exams, everything was by the book. Even after years, nothing changed, and they retired the same way” (P9). This unwavering commitment to the curriculum provides students with a clear, predictable framework for learning, ensuring consistency in expectations and evaluations.

Resistance to change

A hallmark of orderly leadership is a cautious approach to innovation, favoring proven methods over experimental techniques. Instructors in this category often view repetition and consistency as essential for skill mastery. One participant explained, “Consistency in internships isn’t bad. Repetition helps students master skills. Those who haven’t interned with me prepare in advance. They know I value nursing references, so they come ready to follow protocols” (P4). Others attribute their teaching style to longstanding traditions, as one instructor stated: “I developed this teaching method through experience. My instructors during undergrad influenced me, and I see no need to change it now” (P3). While some acknowledge the potential benefits of new approaches, they emphasize the importance of stability and risk aversion: “Early on, with less experience, I kept changing my approach. But now I know how to manage students. New methods must align with student and ward conditions. You can’t just take risks” (P8, P2). Even in exceptional circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, orderly leaders prioritize practicality over innovation, as one participant recalled: “Even during COVID, we tried holding masked in-person classes because nursing can’t be learned virtually. But we complied when remote learning became mandatory” (P8, P2).

Supporter in personal development

It consisted of two subcategories: “Facilitation and support for students” and “fostering individual attitudes and motivation.”

Facilitation and support for students

Effective nursing instructors adopt a student-centered approach by tailoring their teaching methods to individual readiness levels. This dynamic style of instruction recognizes that learners progress at different paces and require varying degrees of guidance. One participant noted, “Where needed, we guide our colleagues and students; other times, we just consult. It depends on the student’s level” (P2). Some students thrive with minimal supervision: “Some students are self-driven. They seek out learning opportunities and progress with minimal supervision” (P1). While others need structured support, as stated by another participant: “Some students want to perform tasks but lack the ability. You must assess and guide them accordingly” (P3). Instructors employ initial assessments to gauge competencies, including communication skills and prior experience. One explained, “On the first day, I evaluate their communication skills and background, where they’re from, and other factors” (P7). While another described asking, “I ask about their prior experiences, which wards they’ve been in, how many IV insertions they’ve done” (P3). This adaptive teaching ensures that support is appropriately calibrated, fostering gradual independence.

Fostering individual attitudes and motivation

Beyond skill acquisition, supportive instructors cultivate professional attitudes by encouraging critical thinking, self-sufficiency, and reflective practice. They engage students in applying theoretical knowledge to real-world scenarios: “When they taught us the Morse and Braden scales, we had to categorize patients at risk of falls based on dizziness or poor condition” (P11). Students are prompted to analyze discrepancies between textbook protocols and clinical realities, as one participant noted: “The dietary plans for infectious or burn patients in textbooks differ from real practice. Critically analyzing these differences helps us think creatively and find solutions” (P9). Goal setting and self-assessment are also prioritized, with instructors soliciting student feedback to reinforce learning ownership. One instructor explained, “I take feedback from students regarding how close they came to their goals, whether they sought solutions and their impact on the ward. Effectiveness helps them identify strengths and weaknesses” (P2, P3, P7). Such strategies enhance clinical competence while nurturing the problem-solving resilience essential for nursing practice.

Sociable leadership

It consists of “communication with others to facilitate education” and “inspirational leadership is its subcategories.”

Communication with others to facilitate education

Sociable instructors create an inclusive learning environment by actively engaging students, healthcare staff, and patients in the educational process. One participant emphasized that they value open communication and mutual decision-making: “Students have the right to criticize. They have the right to make suggestions, and this decision-making process is entirely mutual. Everyone around me has the right to express their opinions” (P2, P3, P8). This collaborative spirit extends to interdisciplinary teamwork, where instructors negotiate with medical staff: “I tell the resident, ‘Would you allow me to transfer this traction to the center?’ After building trust, the next step is telling them, ‘Look, you need to start amiodarone or catheterize your patient.’ I provide comments” (P4).

Patients become active participants in learning: “I tell the patient, ‘I want to hold a class at your bedside where you will be the teacher...’ The patient feels a sense of pride and says, ‘Oh, I have something to contribute here too” (P4). Institutional stakeholders are involved through strategies like “360-degree evaluations,” where “nine points of a student’s evaluation depend on the head nurse’s assessment” (P2, P7). Nurses become educational allies, ensuring continuity of supervision: “If I am momentarily engaged with another student, that nurse pays attention to the students” (P3, P4). This networked approach enriches learning through diverse perspectives.

Inspirational leadership

These instructors leave lasting impressions through compassion and fostering student self-worth. Their patient interactions model empathy, with participants recalling an instructor who “spoke to patients with motherly kindness. There was a warmth in their demeanor, especially when entering a room” (P9, P10). Such mentors remain influential long after formal instruction ends: “Students still consult me even after I’m no longer teaching them” (P2, P3, P8). Learners internalize their professional ethos: “I’ve adopted behavioral traits from an instructor I once had, and I still apply them in relevant situations” (P3, P6, P10).

Crucially, they cultivate confidence by avoiding punitive correction. Students noted: “When the instructor isn’t watching, we perform IV insertions with more confidence and less anxiety” (P7, P8) and appreciated discretion in error management: “If a patient’s vein is damaged, I don’t embarrass or disrespect them in front of their family” (P3, P8).

Sociable leadership redefines nursing education as a collective endeavor. By democratizing input, humanizing patient care, and inspiring through example, these instructors nurture resilient professionals who value teamwork, empathy, and lifelong learning. Their legacy lies in transferring skills and the cultural shift toward inclusive, dignity-affirming healthcare environments.

Discussion

This study explored the leadership styles of clinical nursing faculty at Guilan University of Medical Sciences, offering key insights into how these styles influence nursing students’ learning experiences. The findings reveal that leadership in nursing education involves a complex mix of constructive and harmful styles, each significantly shaping students’ professional growth and preparedness.

A particularly troubling discovery was the prevalence of self-centered and non-constructive leadership traits, such as intellectual arrogance, unfair treatment, and humiliation. These behaviors foster a toxic learning environment, diminishing student motivation and engagement. Research consistently links authoritarian or belittling leadership in healthcare education to heightened student anxiety, lower self-confidence, and poorer clinical performance [17]. In nursing education, where psychological safety is crucial for skill development, such behaviors can also obstruct the formation of a strong professional identity [18]. These behaviors—intellectual arrogance, injustice, and humiliation—collectively reflect self-centered instructional approaches that hinder student growth, foster resentment, and undermine the educational process. Addressing such tendencies is crucial to cultivating a supportive and equitable learning atmosphere.

Similarly, while well-intentioned, preemptive compassion can prove counterproductive. Paternalistic actions, such as overprotecting students from challenges or offering condescending guidance, may inadvertently suppress critical thinking and clinical decision-making. This aligns with studies showing that overly protective teaching styles hinder nursing students’ resilience and problem-solving abilities [19]. Given that nursing practice requires independent judgment, educators must balance support with experiential learning, a principle central to Benner’s [20] novice-to-expert framework [21]. Preemptive compassion, whether through benevolent deterrence or patronizing oversight, reflects instructors’ attempts to safeguard students and patients. However, excessive strictness or control may inadvertently hinder professional growth. Striking a balance between guidance and autonomy is essential to cultivating confident, competent practitioners.

Conversely, the study highlighted supportive leadership styles that significantly enhance student development. Faculty who fostered personal and academic growth through mentorship, motivation, and tailored guidance helped students build greater confidence and competence. These findings align with transformational leadership theory [22, 23], emphasizing how inspiring and supportive leaders improve engagement and performance. In nursing education, transformational leadership correlates with higher student satisfaction, clinical proficiency, and professional commitment [24]. Uncommitted leadership in clinical instruction creates significant barriers to student learning and professional development. When instructors neglect their teaching responsibilities, provide inadequate supervision, and fail to advocate for students’ needs, they foster an environment of disengagement and inequity. Effective clinical education requires dedicated mentorship that combines structured skill development with strong advocacy to ensure students receive the competence and confidence needed for professional practice. Addressing these leadership deficiencies is essential for creating clinical learning environments supporting nursing students’ growth.

Regarding orderly leadership, it should be said this leadership style offers stability and clarity, ensuring that students receive consistent, curriculum aligned instruction. While this approach minimizes confusion and maintains high standards, its resistance to change may limit adaptability in evolving educational landscapes. Balancing structure with flexibility could enhance this leadership style, allowing for incremental improvements while preserving the reliability that defines it. Ultimately, orderly leadership fosters a disciplined learning environment, preparing students for the rigorous demands of the nursing profession. Personal development support transcends traditional instruction by harmonizing individualized guidance with motivational mentorship. Their focus on readiness assessment, adaptive teaching, and reflective engagement empowers students to transition from supervised learners to autonomous professionals. By fostering self-awareness and critical thinking, these instructors ensure that students become skilled practitioners and adaptive, confident contributors to patient care. This approach exemplifies the transformative potential of nursing education when pedagogy aligns with the developmental needs of future nurses.Additionally, sociable leadership styles such as open communication and inspirational guidance proved vital in fostering a collaborative learning atmosphere. Leaders who build trust and encourage dialogue empower students to engage in reflective practice and teamwork, essential skills in nursing, where interprofessional collaboration is critical to patient care [19]. Cummings et al. further reinforced this, identifying communication and emotional intelligence as key components of effective healthcare leadership [23].

These findings underscore the need for nursing programs to prioritize faculty leadership development. Institutions should implement targeted training in emotional intelligence, conflict resolution, and transformational leadership to reduce harmful styles and reinforce positive practices. Formal mentorship programs pairing new educators with experienced leaders could further model effective teaching strategies. Additionally, integrating leadership competencies into faculty evaluations, as recommended by the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN), would ensure accountability in cultivating inclusive, student-centered learning environments [25].

While this study provides valuable insights, its single-institution focus limits generalizability. Future research should expand to multiple centers to explore cultural and organizational variations in leadership. Longitudinal studies could assess how faculty leadership affects long-term outcomes, such as licensure pass rates, job retention, and clinical performance. Additionally, intervention studies evaluating leadership training programs for nursing faculty would strengthen evidence-based practices in nursing education. This study reveals that supportive clinical nursing faculty leadership styles (mentorship, motivation) and harmful (arrogance, unfairness) significantly shape students’ learning and growth. Nursing programs should prioritize faculty training in emotional intelligence and transformational leadership while implementing mentorship and accountability measures. Further multi-institutional research is needed to assess long-term impacts and cultural influences. Empowering educators is key to developing competent, resilient nurses for future healthcare challenges.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1402.010). Informed consent was obtained from all participants

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Ali Bazzi, approved by the Department of Medical _Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: 9941). This study was financially supported by the Deputy for Research of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, visualization, and writing the original draft: Moluk Pouralizadeh; Methodology and supervision: Abbad Ebadi; Data curation, validation, funding acquisition, and project administration: Moluk Pouralizadeh, Abbad Ebadi, Ali Bazzi, and Ehsan Kazemnejad; Review and editing: All authors

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Deputy for the Research at Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran and the professors and students participating in the research project.

References

Effective leadership in nursing education is critical for fostering student engagement, clinical competence, and evidence-based curricula [1-3]. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated transformative shifts in clinical education, including rapid adoption of virtual technologies (e.g. simulation, virtual reality) and evolving student expectations shaped by digital and social media [4]. While nursing leaders are accustomed to change, these developments demand unprecedented adaptability in pedagogical strategies and leadership styles [5]. Current research emphasizes clinical skill development but overlooks nursing educators model leadership in academic settings [6]. This gap hinders the preparation of future nurse leaders capable of navigating complex and technology-driven healthcare environments. Furthermore, faculty evaluations often informed by student feedback rarely assess leadership approaches, despite their impact on teaching quality and educational outcomes [7, 8].

While quantitative studies on leadership styles prioritize measurable behaviors (e.g. feedback frequency) [9] and identify correlations (e.g. transformational leadership and student satisfaction) [10], they inadequately explain how trust is cultivated or why hierarchical methods conflict with digitally native learners’ expectations [11]. This qualitative study addresses these gaps by synthesizing faculty and student perspectives, revealing leadership as co-constructed through interactions. Faculty narratives expose intentional strategies (e.g. balancing safety and autonomy), while student accounts highlight perceived impacts (e.g. empowerment vs humiliation), offering a holistic view of leadership dynamics [12]. Involving both groups captures the bidirectional nature of educational relationships, aligning educators’ intentions with learners’ experiences [13]. This study aimed to explore the educational leadership styles exhibited by clinical nursing faculties in clinical practice settings.

Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative research design with a conventional content analysis approach, allowing categories and themes to emerge directly from the data. This methodology ensures that the findings are rooted in participants’ experiences and perspectives without relying on pre-established frameworks [13, 14].

The study included 11 participants, comprising academic and non-academic faculty, educational staff, undergraduate and graduate nursing students, educational supervisors, and deputies. Purposive sampling was used to ensure diversity in age, gender, educational background, work experience, and academic standing, thereby capturing various perspectives on educational leadership in clinical nursing practice.

Participants were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: Experience in educational or clinical nursing activities, a willingness to participate in the study, and the ability to communicate their experiences and perspectives effectively. Individuals were excluded if they lacked direct experience in clinical or educational nursing roles, declined to provide informed consent, had language barriers or scheduling conflicts preventing full participation in interviews, and were currently or recently (within the past six months) in similar studies to avoid response bias. Data collection was primarily done through semi-structured interviews, supplemented by observations and field notes. The analysis followed the conventional content analysis approach, including coding, categorization, theme extraction, and final interpretation.

Interviews were conducted in private, quiet settings within the nursing school or affiliated hospitals, including offices, educational rooms (e.g. classrooms or workshops), and conference rooms. Each interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim. Broad, open-ended questions were initially posed to encourage openness, with more specific questions based on participants’ responses. The interviews began with the broad, open-ended prompt: “Can you share your experiences regarding the leadership styles of nursing educators in clinical practice?” Exploratory prompts such as “Can you elaborate?” or “Could you provide an example?” were used when needed. Participants were encouraged to share experiences related to challenging situations, conflicts, student feedback, and behaviors aimed at achieving educational goals. Techniques like silence, echoing statements, and verbal affirmations facilitated the process.

The final interview questions were developed with input from the research team and a review of relevant qualitative studies. Data collection continued until saturation was reached, meaning no new themes emerged. Interviews typically lasted 40-55 minutes. Transcripts were reviewed multiple times and analyzed following Graneheim and Lundman’s method, which involves transcribing interviews, extracting meaningful essences, labeling them as semantic units, categorizing them, and assigning abstract titles known as codes to create main categories [15]. The study was done during July to October 2024.

To ensure credibility and trustworthiness, several strategies were employed. Member checking was implemented, where participants reviewed preliminary findings for accuracy. Data triangulation was used by incorporating interviews, observations, and field notes, strengthening the consistency and depth of the findings. Peer review by qualitative research experts validated the methodology, ensuring adherence to standards. The data collection and analysis process were meticulously documented, maintaining an audit trail for transparency and verification of decisions. These strategies enhanced the reliability, validity, and depth of the study, providing a nuanced understanding of educational leadership in clinical nursing practice [16]. Data analyses was done by MAXQDA software, version 2020.

Results

Data saturation was achieved with 11 participants (5 men and 6 women; mean age: 37.54 3.5 years). Participants included nursing faculties, educational supervisors, and undergraduate/graduate students with diverse clinical experience and academic roles. Additional participant characteristics, including work experience, position, and academic department, are presented in Table 1.

In the initial refinement from the content analysis during fieldwork, 366 codes, 35 subcategories, and 15 categories were extracted. The final refinement from interviews with participants and field notes resulted in the extraction of 6 categories, 13 subcategories, and 40 codes. The main categories included self-centered and non-constructive, preemptive compassion, uncommitted leadership, orderly leadership, supporter in personal development, and sociable leadership (Table 2). The participants’ experiences regarding the extracted codes were categorized separately.

Self-centeredness and non-constructive behaviors” in instructional settings

This category consisted of “intellectual arrogance,” “injustice,” and “humiliation subcategories.”

Intellectual arrogance

Instructors exhibiting intellectual arrogance often prioritize self-display over effective teaching, creating a counterproductive learning environment. This issue manifests in unnecessary displays of knowledge, such as using advanced medical terminology irrelevant to the student’s current level. A participant noted, “We had an instructor who used a lot of medical terminology just to show off. These terms weren’t even related to our semester; they were for higher semesters or maybe even medical school” (participant [P]5). Similarly, one participant explained that excessive personal storytelling detracts from learning: “Instead of teaching what we needed, the instructor would go into lengthy, detailed stories about their own student experiences, which had no connection to our topic” (P11, P6). Frequent, unconstructive criticism further reinforces a hierarchical dynamic, with one student recalling how an instructor repeatedly highlighted a minor clinical error: “From the beginning of the internship until the end, always looking for faults” (P10). Additionally, some instructors undermine student autonomy by performing tasks on their behalf: “Some instructors would perform tasks that were normally our responsibility, just to show they could do them better than us” (P6) or “Instead of letting students practice simple tasks like bandaging, the instructor would do them themselves just to flaunt their skills” (P11). Such behaviors stifle learning by prioritizing the instructor's ego over student development.

Injustice

Discriminatory practices and unfair conflict resolution further erode trust in instructional relationships. Participants reported biased grading, with one stating, “We had an instructor who graded differently based on gender. Once, when grades were released, even the students were surprised and wondered why some got much higher grades” (P5). Task allocation was also inequitable, as “Some instructors would unfairly assign important practical tasks only to certain students, especially in lower semesters” (P9, P11). In conflicts, instructors often sided with senior students or staff without proper investigation: “When a conflict arose between us and a senior student, even though we were in the right, the instructor unjustly sided with the senior student. Their tone and interaction with them were different because they were also their advisor” (P5, P9).

Humiliation

Humiliating tactics, including public correction and verbal intimidation, negatively impact students’ confidence and learning. Some instructors deliberately undermined students perceived as overly confident: “If a student seemed too confident, they would bombard them with questions to put them in their place” (P2). Public shaming was common, with participants describing how “During internships, the instructor would correct our mistakes in front of patients or their families, making us feel insulted and humiliated” (P5, P11, P9). These practices damage self-esteem and discourage active participation in learning environments.

Preemptive compassion

This category consisted of benevolent deterrence and patronizing attitude subcategories.

Benevolent deterrence

Some instructors adopt a disciplinary approach rooted in preemptive compassion, enforcing strict consequences to instill professional behavior. While their intentions may be constructive, their methods sometimes feel excessively punitive. For instance, one participant described an instructor who barred a student from entering the ward for being “30 minutes late, saying, ‘They need to learn that as a nurse, they must arrive on time for shifts. Patient’s life depends on it.’ While the instructor had a point, they were overly strict, like deducting a full grade” (P6). In extreme cases, unprofessional conduct led to significant repercussions, as one participant noted: “A classmate had to repeat the internship or do an extra day with another group due to unprofessional behavior like constant tardiness and unjustified absences” (P5, P9). Though these measures aim to correct behavior, their severity may overshadow their instructive intent.

Patronizing attitude

A well-meaning yet overbearing instructional style can manifest in patronizing behaviors that limit student autonomy. Some instructors adopt an excessively advisory role, constantly reminding students to maximize their learning opportunities: “We had an instructor who would say, ‘Use your time in the ward wisely, don’t waste it on your phone.’ Their intention wasn’t to humiliate us. They genuinely cared” (P5, P9, P11). Others go further, insisting on tightly controlled experiences, as one instructor explained: “I tell students, ‘You may never experience this ward again in your life. Make the most of it.’ I insist we perform diabetic foot dressings, even if we have to coordinate with the head nurse so the intern doesn’t do it” (P4). This lack of trust often stems from past student errors, leading to hypervigilance: “Because students had made medication errors in past internships, they didn’t want the same to happen to us. They’d follow us around or double-check all medications after administration” (P11, P9, P5). Such micromanagement can stifle confidence, as one student lamented: “The instructor wouldn’t let me administer insulin alone” (P11). Another instructor defended their rigid oversight: “I show my seriousness in critical matters concerning patient safety. The student must follow my lead. They can’t act independently. I must check every task” (P3). While these actions arise from a protective instinct, they risk fostering dependency rather than competence.

Uncommitted leadership

The “uncommitted leadership” was another category, and its subcategories consisted of “indifference towards helping students achieve educational goals” and “indifference to motivating and restoring student rights.”

Indifference towards helping students achieve educational goals

Clinical instructors demonstrating uncommitted leadership often fail to provide adequate teaching support, resulting in significant gaps in student skill development and curriculum implementation. Participants reported excessive focus on redundant theoretical content during clinical rotations, with one noting: “We had already covered this theory in previous semesters, yet we still spent excessive time on theoretical issues during internships” (P5, P6, P11). This misalignment between instruction and practical needs left students unprepared for essential assessments, as another participant explained: “For Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCEs), we encountered procedures we had barely practiced, sometimes only once or twice, because instructors prioritized conferences over hands-on training” (P5, P11).

The absence of proper supervision emerged as another critical issue. Students described being left without guidance: “Instructors would simply tell us to handle all the ward’s medications on our own, which was demoralizing without proper oversight” (P5, P9). When students sought clarification, they often received dismissive responses: “Rather than demonstrating techniques, instructors would tell us to refer back to first-semester textbooks or give vague answers like ‘Go read it yourself’” (P6, P11). Furthermore, blurring professional boundaries through excessive personal interactions, such as celebrating birthdays and exchanging gifts, created perceptions of favoritism that compromised the learning environment (field notes).

Indifference to motivating and restoring student rights

This leadership style also manifests inadequate support for students’ basic educational needs and rights. Participants highlighted systemic issues with access to learning spaces: “The conference room was restricted to interns, yet our instructors failed to advocate for our access, even when rooms sat empty” (P9, P11). The consequences were particularly frustrating during peak hours: “While medical students occupied classrooms, we were left wandering the halls searching for study space after 11 AM” (P5).

Even when opportunities existed to support students, instructors frequently acquiesced to administrative barriers without challenge. One participant recalled: “The conference rooms were completely unused during afternoon shifts, but when we tried to access them, our instructor accepted the ward manager’s refusal without question” (P6). Most concerning was instructors’ failure to intervene in student-nurse conflicts, with one admitting: “Students expected me to stand up for them in disputes with nursing staff, but I didn’t fulfill that role” (P8).

Orderly leadership

This category consisted of two subcategories: “Adherence to the curriculum and educational regulations” and “resistance to change.”

Adherence to curriculum and educational regulations

Orderly leadership is characterized by a structured, rule-based approach to teaching, emphasizing curriculum fidelity. Instructors embody this leadership style, prioritizing strict compliance with educational guidelines and ensuring teaching methods align with established standards. One participant noted, “The curriculum is my most important item. I always refer to it, even if another instructor has been teaching the same unit for 10 to 12 years. How they taught doesn’t matter. I follow the curriculum” (P1). Another participant described a colleague who exemplified this approach: “One instructor I worked with strictly followed the rules. Lesson plans, grading, exams, everything was by the book. Even after years, nothing changed, and they retired the same way” (P9). This unwavering commitment to the curriculum provides students with a clear, predictable framework for learning, ensuring consistency in expectations and evaluations.

Resistance to change

A hallmark of orderly leadership is a cautious approach to innovation, favoring proven methods over experimental techniques. Instructors in this category often view repetition and consistency as essential for skill mastery. One participant explained, “Consistency in internships isn’t bad. Repetition helps students master skills. Those who haven’t interned with me prepare in advance. They know I value nursing references, so they come ready to follow protocols” (P4). Others attribute their teaching style to longstanding traditions, as one instructor stated: “I developed this teaching method through experience. My instructors during undergrad influenced me, and I see no need to change it now” (P3). While some acknowledge the potential benefits of new approaches, they emphasize the importance of stability and risk aversion: “Early on, with less experience, I kept changing my approach. But now I know how to manage students. New methods must align with student and ward conditions. You can’t just take risks” (P8, P2). Even in exceptional circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, orderly leaders prioritize practicality over innovation, as one participant recalled: “Even during COVID, we tried holding masked in-person classes because nursing can’t be learned virtually. But we complied when remote learning became mandatory” (P8, P2).

Supporter in personal development

It consisted of two subcategories: “Facilitation and support for students” and “fostering individual attitudes and motivation.”

Facilitation and support for students

Effective nursing instructors adopt a student-centered approach by tailoring their teaching methods to individual readiness levels. This dynamic style of instruction recognizes that learners progress at different paces and require varying degrees of guidance. One participant noted, “Where needed, we guide our colleagues and students; other times, we just consult. It depends on the student’s level” (P2). Some students thrive with minimal supervision: “Some students are self-driven. They seek out learning opportunities and progress with minimal supervision” (P1). While others need structured support, as stated by another participant: “Some students want to perform tasks but lack the ability. You must assess and guide them accordingly” (P3). Instructors employ initial assessments to gauge competencies, including communication skills and prior experience. One explained, “On the first day, I evaluate their communication skills and background, where they’re from, and other factors” (P7). While another described asking, “I ask about their prior experiences, which wards they’ve been in, how many IV insertions they’ve done” (P3). This adaptive teaching ensures that support is appropriately calibrated, fostering gradual independence.

Fostering individual attitudes and motivation

Beyond skill acquisition, supportive instructors cultivate professional attitudes by encouraging critical thinking, self-sufficiency, and reflective practice. They engage students in applying theoretical knowledge to real-world scenarios: “When they taught us the Morse and Braden scales, we had to categorize patients at risk of falls based on dizziness or poor condition” (P11). Students are prompted to analyze discrepancies between textbook protocols and clinical realities, as one participant noted: “The dietary plans for infectious or burn patients in textbooks differ from real practice. Critically analyzing these differences helps us think creatively and find solutions” (P9). Goal setting and self-assessment are also prioritized, with instructors soliciting student feedback to reinforce learning ownership. One instructor explained, “I take feedback from students regarding how close they came to their goals, whether they sought solutions and their impact on the ward. Effectiveness helps them identify strengths and weaknesses” (P2, P3, P7). Such strategies enhance clinical competence while nurturing the problem-solving resilience essential for nursing practice.

Sociable leadership

It consists of “communication with others to facilitate education” and “inspirational leadership is its subcategories.”

Communication with others to facilitate education

Sociable instructors create an inclusive learning environment by actively engaging students, healthcare staff, and patients in the educational process. One participant emphasized that they value open communication and mutual decision-making: “Students have the right to criticize. They have the right to make suggestions, and this decision-making process is entirely mutual. Everyone around me has the right to express their opinions” (P2, P3, P8). This collaborative spirit extends to interdisciplinary teamwork, where instructors negotiate with medical staff: “I tell the resident, ‘Would you allow me to transfer this traction to the center?’ After building trust, the next step is telling them, ‘Look, you need to start amiodarone or catheterize your patient.’ I provide comments” (P4).

Patients become active participants in learning: “I tell the patient, ‘I want to hold a class at your bedside where you will be the teacher...’ The patient feels a sense of pride and says, ‘Oh, I have something to contribute here too” (P4). Institutional stakeholders are involved through strategies like “360-degree evaluations,” where “nine points of a student’s evaluation depend on the head nurse’s assessment” (P2, P7). Nurses become educational allies, ensuring continuity of supervision: “If I am momentarily engaged with another student, that nurse pays attention to the students” (P3, P4). This networked approach enriches learning through diverse perspectives.

Inspirational leadership

These instructors leave lasting impressions through compassion and fostering student self-worth. Their patient interactions model empathy, with participants recalling an instructor who “spoke to patients with motherly kindness. There was a warmth in their demeanor, especially when entering a room” (P9, P10). Such mentors remain influential long after formal instruction ends: “Students still consult me even after I’m no longer teaching them” (P2, P3, P8). Learners internalize their professional ethos: “I’ve adopted behavioral traits from an instructor I once had, and I still apply them in relevant situations” (P3, P6, P10).

Crucially, they cultivate confidence by avoiding punitive correction. Students noted: “When the instructor isn’t watching, we perform IV insertions with more confidence and less anxiety” (P7, P8) and appreciated discretion in error management: “If a patient’s vein is damaged, I don’t embarrass or disrespect them in front of their family” (P3, P8).

Sociable leadership redefines nursing education as a collective endeavor. By democratizing input, humanizing patient care, and inspiring through example, these instructors nurture resilient professionals who value teamwork, empathy, and lifelong learning. Their legacy lies in transferring skills and the cultural shift toward inclusive, dignity-affirming healthcare environments.

Discussion

This study explored the leadership styles of clinical nursing faculty at Guilan University of Medical Sciences, offering key insights into how these styles influence nursing students’ learning experiences. The findings reveal that leadership in nursing education involves a complex mix of constructive and harmful styles, each significantly shaping students’ professional growth and preparedness.

A particularly troubling discovery was the prevalence of self-centered and non-constructive leadership traits, such as intellectual arrogance, unfair treatment, and humiliation. These behaviors foster a toxic learning environment, diminishing student motivation and engagement. Research consistently links authoritarian or belittling leadership in healthcare education to heightened student anxiety, lower self-confidence, and poorer clinical performance [17]. In nursing education, where psychological safety is crucial for skill development, such behaviors can also obstruct the formation of a strong professional identity [18]. These behaviors—intellectual arrogance, injustice, and humiliation—collectively reflect self-centered instructional approaches that hinder student growth, foster resentment, and undermine the educational process. Addressing such tendencies is crucial to cultivating a supportive and equitable learning atmosphere.

Similarly, while well-intentioned, preemptive compassion can prove counterproductive. Paternalistic actions, such as overprotecting students from challenges or offering condescending guidance, may inadvertently suppress critical thinking and clinical decision-making. This aligns with studies showing that overly protective teaching styles hinder nursing students’ resilience and problem-solving abilities [19]. Given that nursing practice requires independent judgment, educators must balance support with experiential learning, a principle central to Benner’s [20] novice-to-expert framework [21]. Preemptive compassion, whether through benevolent deterrence or patronizing oversight, reflects instructors’ attempts to safeguard students and patients. However, excessive strictness or control may inadvertently hinder professional growth. Striking a balance between guidance and autonomy is essential to cultivating confident, competent practitioners.

Conversely, the study highlighted supportive leadership styles that significantly enhance student development. Faculty who fostered personal and academic growth through mentorship, motivation, and tailored guidance helped students build greater confidence and competence. These findings align with transformational leadership theory [22, 23], emphasizing how inspiring and supportive leaders improve engagement and performance. In nursing education, transformational leadership correlates with higher student satisfaction, clinical proficiency, and professional commitment [24]. Uncommitted leadership in clinical instruction creates significant barriers to student learning and professional development. When instructors neglect their teaching responsibilities, provide inadequate supervision, and fail to advocate for students’ needs, they foster an environment of disengagement and inequity. Effective clinical education requires dedicated mentorship that combines structured skill development with strong advocacy to ensure students receive the competence and confidence needed for professional practice. Addressing these leadership deficiencies is essential for creating clinical learning environments supporting nursing students’ growth.

Regarding orderly leadership, it should be said this leadership style offers stability and clarity, ensuring that students receive consistent, curriculum aligned instruction. While this approach minimizes confusion and maintains high standards, its resistance to change may limit adaptability in evolving educational landscapes. Balancing structure with flexibility could enhance this leadership style, allowing for incremental improvements while preserving the reliability that defines it. Ultimately, orderly leadership fosters a disciplined learning environment, preparing students for the rigorous demands of the nursing profession. Personal development support transcends traditional instruction by harmonizing individualized guidance with motivational mentorship. Their focus on readiness assessment, adaptive teaching, and reflective engagement empowers students to transition from supervised learners to autonomous professionals. By fostering self-awareness and critical thinking, these instructors ensure that students become skilled practitioners and adaptive, confident contributors to patient care. This approach exemplifies the transformative potential of nursing education when pedagogy aligns with the developmental needs of future nurses.Additionally, sociable leadership styles such as open communication and inspirational guidance proved vital in fostering a collaborative learning atmosphere. Leaders who build trust and encourage dialogue empower students to engage in reflective practice and teamwork, essential skills in nursing, where interprofessional collaboration is critical to patient care [19]. Cummings et al. further reinforced this, identifying communication and emotional intelligence as key components of effective healthcare leadership [23].

These findings underscore the need for nursing programs to prioritize faculty leadership development. Institutions should implement targeted training in emotional intelligence, conflict resolution, and transformational leadership to reduce harmful styles and reinforce positive practices. Formal mentorship programs pairing new educators with experienced leaders could further model effective teaching strategies. Additionally, integrating leadership competencies into faculty evaluations, as recommended by the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN), would ensure accountability in cultivating inclusive, student-centered learning environments [25].

While this study provides valuable insights, its single-institution focus limits generalizability. Future research should expand to multiple centers to explore cultural and organizational variations in leadership. Longitudinal studies could assess how faculty leadership affects long-term outcomes, such as licensure pass rates, job retention, and clinical performance. Additionally, intervention studies evaluating leadership training programs for nursing faculty would strengthen evidence-based practices in nursing education. This study reveals that supportive clinical nursing faculty leadership styles (mentorship, motivation) and harmful (arrogance, unfairness) significantly shape students’ learning and growth. Nursing programs should prioritize faculty training in emotional intelligence and transformational leadership while implementing mentorship and accountability measures. Further multi-institutional research is needed to assess long-term impacts and cultural influences. Empowering educators is key to developing competent, resilient nurses for future healthcare challenges.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1402.010). Informed consent was obtained from all participants

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Ali Bazzi, approved by the Department of Medical _Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: 9941). This study was financially supported by the Deputy for Research of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, visualization, and writing the original draft: Moluk Pouralizadeh; Methodology and supervision: Abbad Ebadi; Data curation, validation, funding acquisition, and project administration: Moluk Pouralizadeh, Abbad Ebadi, Ali Bazzi, and Ehsan Kazemnejad; Review and editing: All authors

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Deputy for the Research at Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran and the professors and students participating in the research project.

References

- Ferreira TDM, de Mesquita GR, de Melo GC, de Oliveira MS, Bucci AF, Porcari TA, et al. The influence of nursing leadership styles on the outcomes of patients, professionals and institutions: An integrative review. J Nurs Manag. 2022; 30(4):936-53. [PMID]

- Diedrichsen KM. Undergraduate nursing faculty’s lived experience of authentic leadership in nursing education [PhD dissertation]. Texas: Bryan College of Health Sciences; 2021. [Link]

- Laamiri FZ, Barich F, Chafik K, Bouzid J, Chahboune M, Elkhoudri N, et al. Study of the clinical learning challenges of Moroccan nursing students. J Holist Nurs Midwifery. 2024; 35(1):81-9. [Link]

- Özdemir N, Gümüş S, Kılınç AÇ, Bellibaş MŞ. A systematic review of research on school leadership and student achievement: An updated framework and future direction. EducManage Adm Leadersh. 2024; 52(5):1020-46. [DOI:10.1177/17411432221118662]

- Zarpullayev N, Balay-Odao EM, Cruz JP. Experiences of nursing students on the caring behavior of their instructors: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ Today. 2024; 141:106311. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106311] [PMID]

- Prasojo LD, Yuliana L, Akalili A. Dataset on factors affecting social media use among school principals for educational leaderships. Data Brief. 2021; 39:107654. [PMID]

- Mukurunge E, Nyoni CN, Hugo L. Context of assessment in competency-based nursing education: Semi-structured interviews in nursing education institutions in a low-income country. Nurse Educ Today. 2025; 146:106529. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106529] [PMID]

- Sahan FU, Terzioglu F. Transformational leadership practices of nurse managers: The effects on the organizational commitment and job satisfaction of staff nurses. Leadership in Health Services. 2022; 35(4):494-505. [DOI: 10.1108/LHS-11-2021-0091] [PMID]

- Lee H, Song Y. Kirkpatrick model evaluation of accelerated second-degree nursing programs: A scoping review. J Nurs Educ. 2021; 60(5):265-71. [DOI:10.3928/01484834-20210420-05] [PMID]

- Karaman F, KavgaoĞlu D, Yildirim G, Rashidi M, Ünsal Jafarov G, Zahoor H, et al. Development of the educational leadership scale for nursing students: A methodological study. BMC Nurs. 2023; 22(1):110. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-023-01254-4] [PMID]

- Khan HSud, Chughtai MS, Ma Z, Li M, He D. Adaptive leadership and safety citizenship behaviors in Pakistan: The roles of readiness to change, psychosocial safety climate, and proactive personality. Frontiers in Public Health. 2024; 11:1298428. [DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1298428] [PMID]

- Démeh W, Rosengren K. The visualisation of clinical leadership in the content of nursing education--a qualitative study of nursing students' experiences. Nurse Educ Today. 2015; 35(7):888-93. [PMID]

- Karimi Moonaghi H, Ramezani M, Amini S, Khodadadi Hosseini BM, Keykha A. Spiritual challenges of family caregivers of patients in a vegetative state: A qualitative content analysis. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2024; 13(3):124-30. [DOI:10.34172/jqr.2024.18]

- Johnson JL, Adkins D, Chauvin S. A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020; 84(1):7120. [DOI:10.5688/ajpe7120] [PMID]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004; 24(2):105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

- Laschinger HK, Wong CA, Grau AL. Authentic leadership, empowerment and burnout: A comparison in new graduates and experienced nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2013; 21(3):541-52. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01375.x] [PMID]

- Alrobai T. The impact of nurse leaders/managers leadership style on job satisfaction and burnout among qualified nurses: A systematic review. J Nurs Health Sci. 2020; 9(5):17-41. [Link]

- van Diggele C, Burgess A, Roberts C, Mellis C. Leadership in healthcare education. BMC Med Educ. 2020; 20(Suppl 2):456.[DOI:10.1186/s12909-020-02288-x] [PMID]

- Clipper B. The innovation handbook: A nurse leader’s guide to transforming nursing. Indiana: Sigma Theta Tau; 2023. [Link]

- Benner P. From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Am J Nurs. 1984; 84(12):1479. [DOI:10.1097/00000446-198412000-00025]

- Bass BM, Avolio BJ. Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. [Link]

- Hutchinson M, Jackson D. Transformational leadership in nursing: Towards a more critical interpretation. Nurs Inq. 2013; 20(1):11-22.[DOI:10.1111/nin.12006] [PMID]

- Cummings GG, Tate K, Lee S, Wong CA, Paananen T, Micaroni SPM, et al. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018; 85:19-60. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.04.016] [PMID]

- Lee NPM, Chiang VCL. The mentorship experience of students and nurses in pre-registration nursing education: A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Nurs Health Sci. 2021; 23(1):69-86. [DOI: 10.1111/nhs.12794] [PMID]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. AACN essentials [internet]. 2021. [Updated 2025 July 22]. Available from: [Link]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2024/12/21 | Accepted: 2025/04/30 | Published: 2025/06/10

Received: 2024/12/21 | Accepted: 2025/04/30 | Published: 2025/06/10

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |