Sat, Nov 22, 2025

Volume 35, Issue 4 (9-2025)

JHNM 2025, 35(4): 286-294 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hasankhani H, Ghanbari Khanghah A, Nasiri K, Javadi-Pashaki N. Migration Intention and Its Reasons Among Nursing Students: A Systematic Revie. JHNM 2025; 35 (4) :286-294

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2466-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2466-en.html

1- Nursing (Msn), Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- PhD Candidate, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- Professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,n.javadip@gmail.com

2- Professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- PhD Candidate, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- Professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 575 kb]

(351 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (222 Views)

Full-Text: (244 Views)

Introduction

In today’s dynamic world, human resource is a key factor in driving organizational change and achieving its goals [1]. Skilled and well-equipped workers are essential to the success of organizations [2]. Managing an organization requires staffing it with competent personnel [3]. The organization’s reliance on human capital for success and survival is growing due to the increasing complexity of the organizational environment in the 21st century [4]. Nurses, as the backbone of the healthcare system, provide essential services, continuity of care, and health promotion. The shortage of nursing staff around the world is affected by several factors, such as poor work environment, job burnout, lack of professional identity, and migration. Nurses need higher wages, a desire for professional experience [5, 6], and better and more specialized education [5].

Migration is expected to be inevitable, leading to a global shortage of nurses and the increasing demand for health care worldwide [7]. Thousands of nurses migrate every year, but there is little information about their reasons for migration [8]. The nurses’ migration may be explained by the favorable and attractive living conditions in foreign countries [9]. Favorable perceptions of brain drain among nursing students are likely to shape their post-graduation migration choices [10]. With greater attractions and repulsions from foreign countries, elites are more likely to migrate and perceive the benefits of migration [11]. Thus, various factors play a role in the intention for brain drain [12]. Identifying these factors is crucial for promoting long-term commitment and retention among nurses. By understanding these factors, policymakers can develop effective strategies to recruit and retain nurses in the workforce. Therefore, this study aims to review the reasons for migration in nursing students by examining push and pull factors. This study can help better understand the challenges and opportunities faced by nursing students.

Materials and Methods

This is a systematic review study. In order to identify relevant studies from 2000 to 2023, a search was conducted in databases, including PubMed-Medline, Scopus, EMBASE, the Web of Science (WoS), CINHAL, EBSCO, and the Google Scholar search engine. English-language observational or quantitative studies in which the target population was nursing students (not nurses) and whose full text was available were included. The review articles, letters to the editors, short reports, conference abstracts, dissertations, or studies with no available full‐texts were excluded. The search strategy is shown in Table 1.

Data extraction and assessment of the methodological quality of studies were carried out independently by two researchers. The disagreements were resolved through consensus discussion with the third researcher. The data were reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist [13].

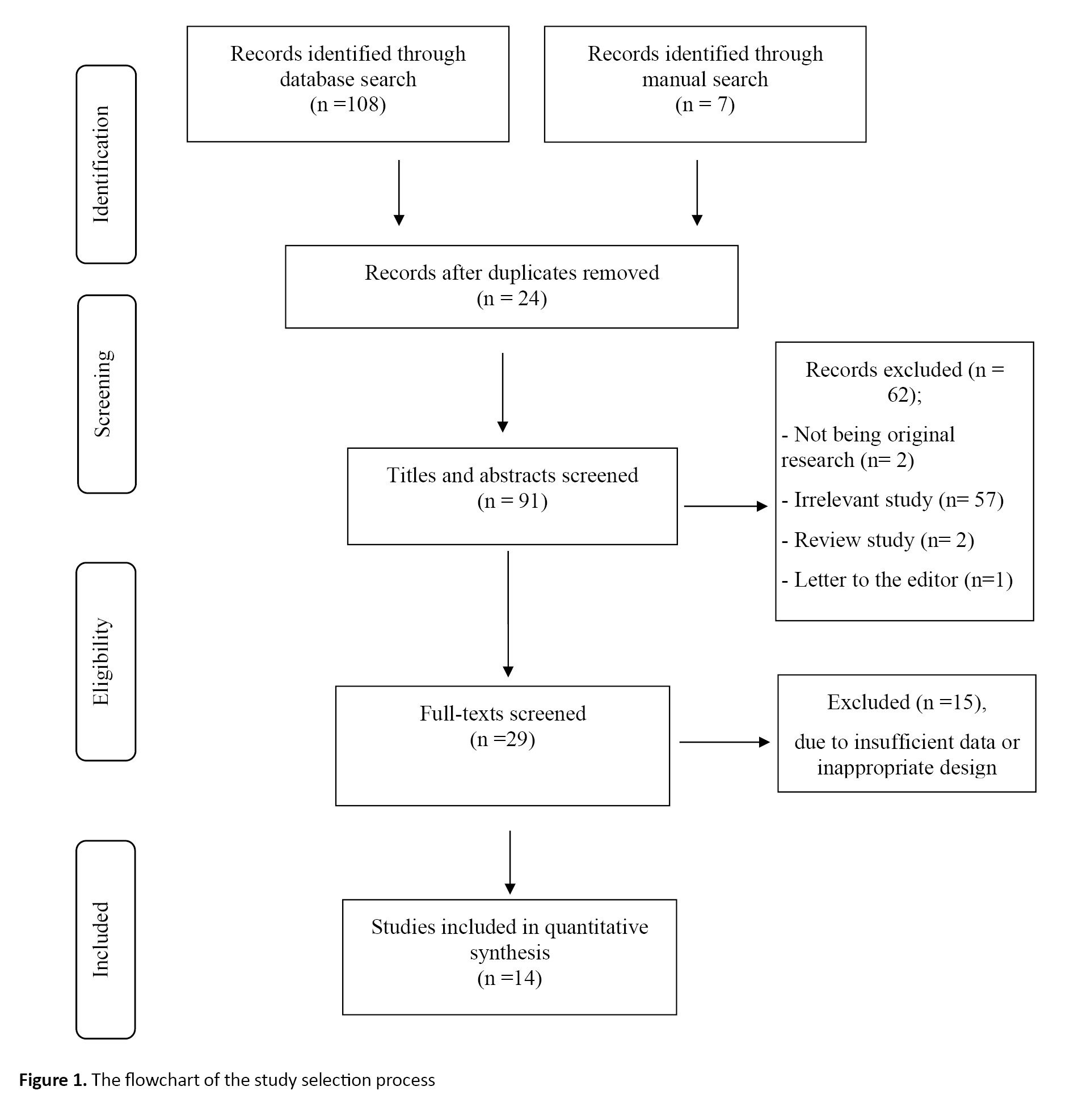

The initial search yielded 115 documents, of which 24 duplicates were removed; the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were then screened. Due to not meeting the inclusion criteria, 62 articles were excluded. The full texts of the remaining 29 articles were read, which led to the exclusion of 15 articles due to insufficient data or inappropriate study design. Finally, 14 articles were selected for the review. Figure 1 shows the diagram of the study selection process. The 22-item Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist was for the evaluation of different parts of observational studies, including: Title, abstract, objectives, statement of the problem, type of study, sampling method, study population, sample size, definition of variables, study data collection tool, statistical analysis, findings and discussion. If the item was mentioned in the appropriate section of the article, it received one point, and if not, a zero point was given. The checklist’s total score ranges from 0 to 32. A score of 16 or above indicates a high or moderate quality, while a score <16 indicates low quality. All studies that scored 16 or higher were included. The authors’ names, study year, study country, sample size, male-to-female ratio (M/F), age of participants, educational level of participants, pull factors, push factors, intentions to migrate, and key findings of selected articles were extracted.

Results

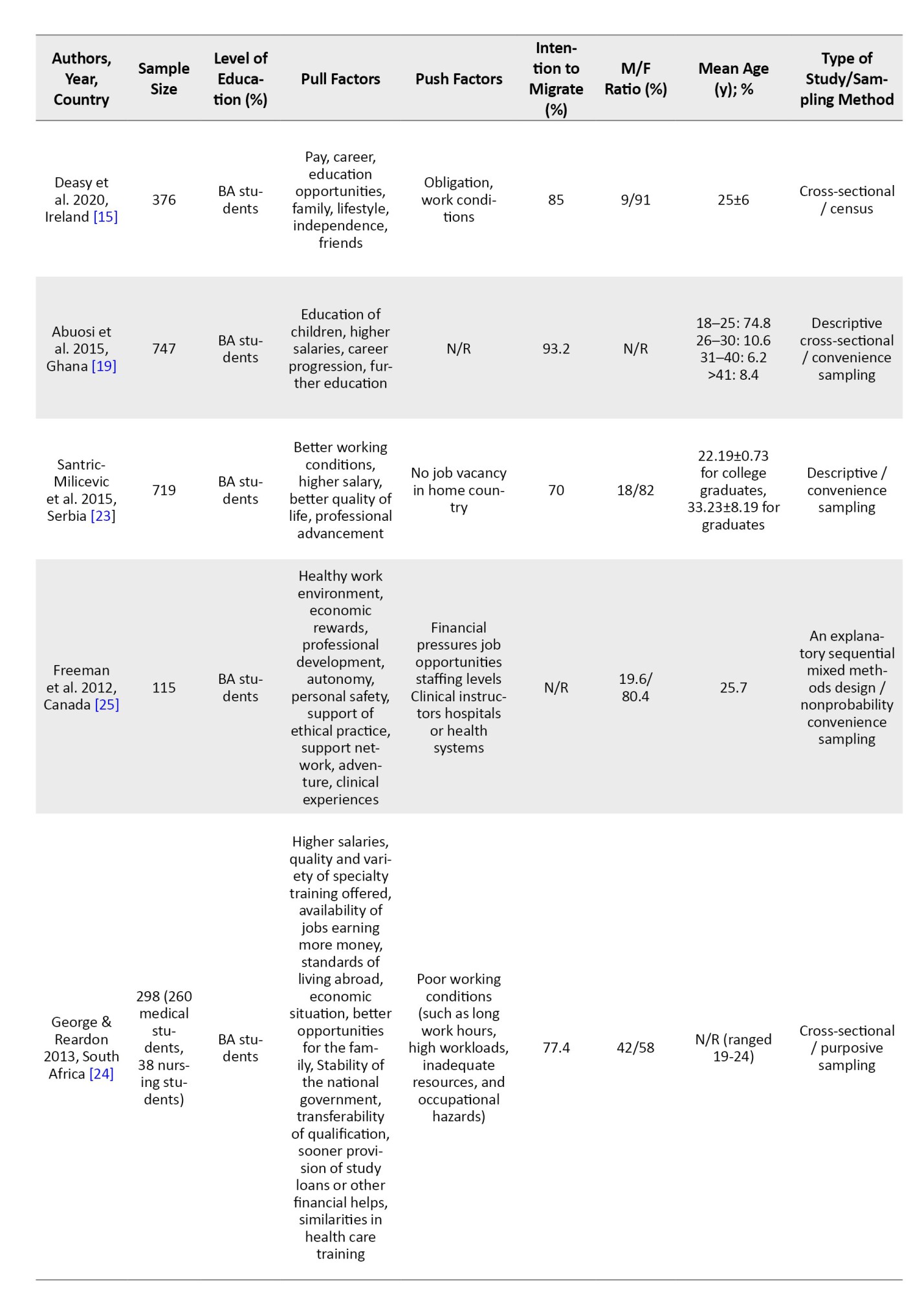

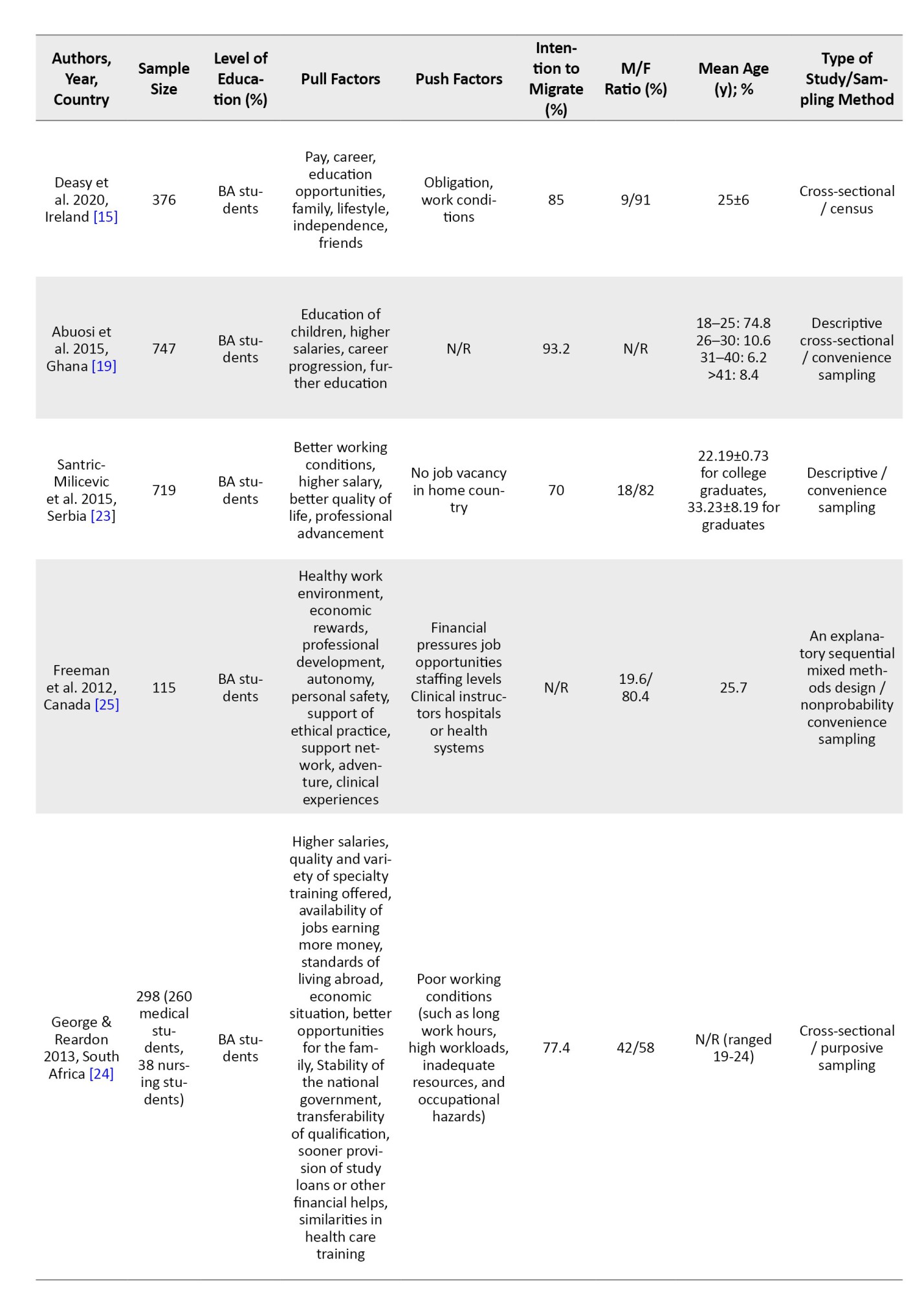

Fourteen articles were reviewed. Their characteristics are presented in Table 2.

In 11 study results, over 60 % of nursing students had the intention to migrate (ranging from 15.8% to 93.2%). Most of the studies were conducted in African (n=5) and Asian (n=4) countries. The sample size ranged from 115 to 3,199. Most participants were females and under 30 years old. Most studies (n=8) were cross-sectional [6, 15-24] and used a convenience sampling method (n=6) [16, 18-20, 23, 25]. Salary and financial factors (n=9) [6, 15-19, 23-25], personal and family factors (n=8) [6, 15, 18-20, 24-26], professional development (n=9) [6, 15, 17-20, 23-25], lifestyle and well-being (n=5) [16, 18, 23-25], socio-political factors (n=4) [6, 21, 24, 25], continuation of education and learning (n=5) [6, 15, 18, 19, 26], future work/work conditions (n=3) [16, 17, 23] were the most prevalent pull factors for migration. Also, the most prevalent push factor for intention to migrate was working conditions (n=8) [6, 15, 16, 18, 21, 23-25], followed by socio-political factors (n=5) [16-18, 20, 26], salary and financial factors (n=4) [16, 18, 25, 26], continues education (n=3) [17, 18, 26], professional factors (n=1) and personal factors (n=1) [15].

Discussion

Nurses are a significant group of healthcare providers with a high rate of migration to foreign countries [27]. A study in Nepal found that 3,461 Nepali nurses migrated for better opportunities from 2002 to 2011 [26]. A study in India indicated a growing global demand for nurses, leading to increased migration [28]. The profession provides nurses with a deeper understanding of the world, enabling them to make decisions based on their own situation and that of others [29]. Given the crucial role of nurses in providing healthcare services, understanding their reasons for migration is essential for the health system. This review study aimed to investigate the pull and push factors of intention to migrate among nursing students.

The results revealed their high intention to migrate. Most nursing students with the intention to migrate were female, likely due to the nursing profession’s female-dominated nature. This gender difference should not be interpreted as a factor influencing migration. Financial factors were identified as the most prevalent reason for migration. According to the results of several studies, one of the main reasons for the migration of healthcare professionals is to earn more money [30-33]. Healthcare professionals from developing countries, facing economic, social, and environmental challenges, often migrate to other countries in search of better working conditions and higher pay [34]. In addition, the increased nurse migration in developing countries can be due to the globalization of the nursing workforce [35]. In this study, we also found that nursing students from less developed countries, such as African and Asian countries, were more likely to migrate.

Other factors that caused nursing students to migrate included family and economic factors. The main goal of migration is to improve living conditions [21]. The results of a study in South Korea indicated that nurses migrated for a variety of reasons, including quality of life and professional development [18]. The desire for migration arises when the home country is unable to meet the social and political expectations of immigrants, while the destination country has attractive characteristics and a higher level of welfare [36]. Nurse migration is pushed by poor living conditions, political instability, obligation, safety issues, limited employment, weak health care management, and an uncertain future [22, 37].

Personal growth, more education opportunities, and the possibility of further study were other reasons for nursing students’ interest in moving to another country. The opportunities available for study and work in different countries can affect the intention to migrate [38]. In less developed countries, high pressure is put on nurses to follow the doctor’s orders, while in developed countries, nurses are allowed to think critically and make independent decisions, and there are inter-professional and intra-professional equality relationships, patient support, and comprehensive care [39]. According to Smith et al., one of the primary reasons for the migration of healthcare workers is the motivation for personal and professional growth [40]. The poor working conditions in the home country were reported as another push factor for migration among nursing students [41, 42]. A key factor influencing nurses’ workplace choice and thus migration is the lack of job opportunities [37, 38]. Adoption of supportive policies for nurses may seem necessary to retain the nursing workforce.

A key limitation of this study was the inability to conduct a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of the data, the lack of a global standard tool for identifying push and pull factors of migration in nursing students, the diversity of tools and scoring methods used, and the insufficient data reporting in the included studies. Variations in study methods, sample sizes, and cultural contexts made data pooling challenging. The lack of access to the full texts of all articles and books was another limitation of that study. More qualitative and longitudinal studies are recommended to further explore nurses’ reasons for migration.

The study highlights the high migration intention of nursing students worldwide, driven by financial, political, social, and work-related reasons. Addressing the push and pull factors of migration in less developed countries is needed to retain the nursing workforce. An efficient international cooperation is required in order to understand and manage nurses’ migration effectively.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Data collection, statistical analysis, and writing the initial draft: Khadijeh Nasiri and Hanieh Hasankhani; Supervision, review & editing: Nazila Javadi-Pashaki and Atefeh Ghanbari Khanghah; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

In today’s dynamic world, human resource is a key factor in driving organizational change and achieving its goals [1]. Skilled and well-equipped workers are essential to the success of organizations [2]. Managing an organization requires staffing it with competent personnel [3]. The organization’s reliance on human capital for success and survival is growing due to the increasing complexity of the organizational environment in the 21st century [4]. Nurses, as the backbone of the healthcare system, provide essential services, continuity of care, and health promotion. The shortage of nursing staff around the world is affected by several factors, such as poor work environment, job burnout, lack of professional identity, and migration. Nurses need higher wages, a desire for professional experience [5, 6], and better and more specialized education [5].

Migration is expected to be inevitable, leading to a global shortage of nurses and the increasing demand for health care worldwide [7]. Thousands of nurses migrate every year, but there is little information about their reasons for migration [8]. The nurses’ migration may be explained by the favorable and attractive living conditions in foreign countries [9]. Favorable perceptions of brain drain among nursing students are likely to shape their post-graduation migration choices [10]. With greater attractions and repulsions from foreign countries, elites are more likely to migrate and perceive the benefits of migration [11]. Thus, various factors play a role in the intention for brain drain [12]. Identifying these factors is crucial for promoting long-term commitment and retention among nurses. By understanding these factors, policymakers can develop effective strategies to recruit and retain nurses in the workforce. Therefore, this study aims to review the reasons for migration in nursing students by examining push and pull factors. This study can help better understand the challenges and opportunities faced by nursing students.

Materials and Methods

This is a systematic review study. In order to identify relevant studies from 2000 to 2023, a search was conducted in databases, including PubMed-Medline, Scopus, EMBASE, the Web of Science (WoS), CINHAL, EBSCO, and the Google Scholar search engine. English-language observational or quantitative studies in which the target population was nursing students (not nurses) and whose full text was available were included. The review articles, letters to the editors, short reports, conference abstracts, dissertations, or studies with no available full‐texts were excluded. The search strategy is shown in Table 1.

Data extraction and assessment of the methodological quality of studies were carried out independently by two researchers. The disagreements were resolved through consensus discussion with the third researcher. The data were reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist [13].

The initial search yielded 115 documents, of which 24 duplicates were removed; the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were then screened. Due to not meeting the inclusion criteria, 62 articles were excluded. The full texts of the remaining 29 articles were read, which led to the exclusion of 15 articles due to insufficient data or inappropriate study design. Finally, 14 articles were selected for the review. Figure 1 shows the diagram of the study selection process. The 22-item Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist was for the evaluation of different parts of observational studies, including: Title, abstract, objectives, statement of the problem, type of study, sampling method, study population, sample size, definition of variables, study data collection tool, statistical analysis, findings and discussion. If the item was mentioned in the appropriate section of the article, it received one point, and if not, a zero point was given. The checklist’s total score ranges from 0 to 32. A score of 16 or above indicates a high or moderate quality, while a score <16 indicates low quality. All studies that scored 16 or higher were included. The authors’ names, study year, study country, sample size, male-to-female ratio (M/F), age of participants, educational level of participants, pull factors, push factors, intentions to migrate, and key findings of selected articles were extracted.

Results

Fourteen articles were reviewed. Their characteristics are presented in Table 2.

In 11 study results, over 60 % of nursing students had the intention to migrate (ranging from 15.8% to 93.2%). Most of the studies were conducted in African (n=5) and Asian (n=4) countries. The sample size ranged from 115 to 3,199. Most participants were females and under 30 years old. Most studies (n=8) were cross-sectional [6, 15-24] and used a convenience sampling method (n=6) [16, 18-20, 23, 25]. Salary and financial factors (n=9) [6, 15-19, 23-25], personal and family factors (n=8) [6, 15, 18-20, 24-26], professional development (n=9) [6, 15, 17-20, 23-25], lifestyle and well-being (n=5) [16, 18, 23-25], socio-political factors (n=4) [6, 21, 24, 25], continuation of education and learning (n=5) [6, 15, 18, 19, 26], future work/work conditions (n=3) [16, 17, 23] were the most prevalent pull factors for migration. Also, the most prevalent push factor for intention to migrate was working conditions (n=8) [6, 15, 16, 18, 21, 23-25], followed by socio-political factors (n=5) [16-18, 20, 26], salary and financial factors (n=4) [16, 18, 25, 26], continues education (n=3) [17, 18, 26], professional factors (n=1) and personal factors (n=1) [15].

Discussion

Nurses are a significant group of healthcare providers with a high rate of migration to foreign countries [27]. A study in Nepal found that 3,461 Nepali nurses migrated for better opportunities from 2002 to 2011 [26]. A study in India indicated a growing global demand for nurses, leading to increased migration [28]. The profession provides nurses with a deeper understanding of the world, enabling them to make decisions based on their own situation and that of others [29]. Given the crucial role of nurses in providing healthcare services, understanding their reasons for migration is essential for the health system. This review study aimed to investigate the pull and push factors of intention to migrate among nursing students.

The results revealed their high intention to migrate. Most nursing students with the intention to migrate were female, likely due to the nursing profession’s female-dominated nature. This gender difference should not be interpreted as a factor influencing migration. Financial factors were identified as the most prevalent reason for migration. According to the results of several studies, one of the main reasons for the migration of healthcare professionals is to earn more money [30-33]. Healthcare professionals from developing countries, facing economic, social, and environmental challenges, often migrate to other countries in search of better working conditions and higher pay [34]. In addition, the increased nurse migration in developing countries can be due to the globalization of the nursing workforce [35]. In this study, we also found that nursing students from less developed countries, such as African and Asian countries, were more likely to migrate.

Other factors that caused nursing students to migrate included family and economic factors. The main goal of migration is to improve living conditions [21]. The results of a study in South Korea indicated that nurses migrated for a variety of reasons, including quality of life and professional development [18]. The desire for migration arises when the home country is unable to meet the social and political expectations of immigrants, while the destination country has attractive characteristics and a higher level of welfare [36]. Nurse migration is pushed by poor living conditions, political instability, obligation, safety issues, limited employment, weak health care management, and an uncertain future [22, 37].

Personal growth, more education opportunities, and the possibility of further study were other reasons for nursing students’ interest in moving to another country. The opportunities available for study and work in different countries can affect the intention to migrate [38]. In less developed countries, high pressure is put on nurses to follow the doctor’s orders, while in developed countries, nurses are allowed to think critically and make independent decisions, and there are inter-professional and intra-professional equality relationships, patient support, and comprehensive care [39]. According to Smith et al., one of the primary reasons for the migration of healthcare workers is the motivation for personal and professional growth [40]. The poor working conditions in the home country were reported as another push factor for migration among nursing students [41, 42]. A key factor influencing nurses’ workplace choice and thus migration is the lack of job opportunities [37, 38]. Adoption of supportive policies for nurses may seem necessary to retain the nursing workforce.

A key limitation of this study was the inability to conduct a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of the data, the lack of a global standard tool for identifying push and pull factors of migration in nursing students, the diversity of tools and scoring methods used, and the insufficient data reporting in the included studies. Variations in study methods, sample sizes, and cultural contexts made data pooling challenging. The lack of access to the full texts of all articles and books was another limitation of that study. More qualitative and longitudinal studies are recommended to further explore nurses’ reasons for migration.

The study highlights the high migration intention of nursing students worldwide, driven by financial, political, social, and work-related reasons. Addressing the push and pull factors of migration in less developed countries is needed to retain the nursing workforce. An efficient international cooperation is required in order to understand and manage nurses’ migration effectively.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Data collection, statistical analysis, and writing the initial draft: Khadijeh Nasiri and Hanieh Hasankhani; Supervision, review & editing: Nazila Javadi-Pashaki and Atefeh Ghanbari Khanghah; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Jahangiri S, Rasouli E, Ebrahimpour H, Rouhi Esalu M, Khairandish M. [A comparative study of human resource selection in Medical Universities of Iran and World (Persian)]. J Health Hygiene. 2021; 11(5):714-32. [Link]

- Zali M, Ghofrani M, Orujlu S. [Nursing human resource management facing Covid-19: An integrative review (Persian)]. Faslname-I Mudiriyyat-E Parastari. 2022; 10(4):38-48. [Link]

- Mnim GO. Human resource development and organizational survival of selected public agencies in rivers state. BW Acad J. 2025; 13(1):90-9. [Link]

- Ngene G, Egwuagu U, Nnamani D. Human resource management and digitalization in 21st century. J Policy Dev Stud. 2024; 17(2):18-35. [DOI:10.4314/jpds.v17i2.2]

- Gebregziabher D, Berhanie E, Berihu H, Belstie A, Teklay G. The relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention among nurses in Axum comprehensive and specialized hospital Tigray, Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2020; 19:79. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-020-00468-0] [PMID]

- Palese A, Falomo M, Brugnolli A, Mecugni D, Marognolli O, Montalti S, et al. Nursing student plans for the future after graduation: A multicentre study. Int Nurs Rev. 2017; 64(1):99-108. [DOI:10.1111/inr.12346] [PMID]

- Stokes F, Iskander R. Human rights and bioethical considerations of global nurse migration. J Bioeth Inq. 2021; 18(3):429-39. [DOI:10.1007/s11673-021-10110-6] [PMID]

- Valizadeh S, Hasankhani H, Shojaeimotlagh V. Nurses’ immigration: causes and problems. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2016; 5(9S):486-91. [Link]

- Kamali M, Niromand Zandi K, Ilkhani M, Shakeri N, Rohani C. [The relationship between job satisfaction and desire to emigrate among the nurses of public hospitals in Tehran (Persian)]. J Health Adm. 2020; 23(3):11-6. [DOI:10.29252/jha.23.3.11]

- Guven Ozdemir N, Tosun S, Gokce S, Karatas Z, Yucetepe S. Factors influencing attitudes towards brain drain among nursing students: A path analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2024; 143:106389. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106389] [PMID]

- Moghimi SM. [Investigating the impact of talent management on the employment and attraction of elites and its effects on reducing the migration of elites in the country (Persian)]. Bus Manag. 2018; 39(10):113-31. [Link]

- Vega-Muñoz A, Gónzalez-Gómez-del-Miño P, Espinosa-Cristia JF. Recognizing new trends in brain drain studies in the framework of global sustainability. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3195. [DOI:10.3390/su13063195]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010; 8(5):336-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007] [PMID]

- Ramke J, Palagyi A, Jordan V, Petkovic J, Gilbert CE. Using the STROBE statement to assess reporting in blindness prevalence surveys in low and middle income countries. Plos One. 2017; 12(5):e0176178. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0176178] [PMID]

- Deasy C, O Loughlin C, Markey K, O Donnell C, Murphy Tighe S, Doody O, et al. Effective workforce planning: Understanding final-year nursing and midwifery students' intentions to migrate after graduation. J Nurs Manag. 2021; 29(2):220-8. [DOI:10.1111/jonm.13143] [PMID]

- Nguyen L, Ropers S, Nderitu E, Zuyderduin A, Luboga S, Hagopian A. Intent to migrate among nursing students in Uganda: measures of the brain drain in the next generation of health professionals. Hum Resour Health. 2008; 6:5. [DOI:10.1186/1478-4491-6-5] [PMID]

- Hendel T, Kagan I. Professional image and intention to emigrate among Israeli nurses and nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2011; 31(3):259-62. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2010.11.008] [PMID]

- Lee E, Moon M. Korean nursing students' intention to migrate abroad. Nurse Educ Today. 2013; 33(12):1517-22. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2013.04.006] [PMID]

- Abuosi AA, Abor PA. Migration intentions of nursing students in Ghana: Implications for human resource development in the health sector. J Int Migr Integr. 2015; 16(3):593-606. [DOI:10.1007/s12134-014-0353-5]

- Lee E. Factors Influencing the Intent to Migrate in Nursing Students in South Korea. J Transcult Nurs. 2016; 27(5):529-37. [DOI:10.1177/1043659615577697] [PMID]

- Öncü E, Vayısoğlu SK, Karadağ G, Alaçam B, Göv P, Selçuk Tosun A, et al. Intention to migrate among the next generation of Turkish nurses and drivers of migration. J Nurs Manag. 2021; 29(3):487-96. [DOI:10.1111/jonm.13187] [PMID]

- Efendi F, Oda H, Kurniati A, Hadjo SS, Nadatien I, Ritonga IL. Determinants of nursing students' intention to migrate overseas to work and implications for sustainability: The case of Indonesian students. Nurs Health Sci. 2021; 23(1):103-12. [DOI:10.1111/nhs.12757] [PMID]

- Santric-Milicevic M, Matejic B, Terzic-Supic Z, Vasic V, Babic U, Vukovic V. Determinants of intention to work abroad of college and specialist nursing graduates in Serbia. Nurse Educ Today. 2015; 35(4):590-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2014.12.022] [PMID]

- George G, Reardon C. Preparing for export? Medical and nursing student migration intentions post-qualification in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2013; 5(1):1-9. [DOI:10.4102/phcfm.v5i1.483]

- Freeman M, Baumann A, Akhtar-Danesh N, Blythe J, Fisher A. Employment goals, expectations, and migration intentions of nursing graduates in a Canadian border city: A mixed methods study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012; 49(12):1531-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.07.015] [PMID]

- Poudel C, Ramjan L, Everett B, Salamonson Y. Exploring migration intention of nursing students in Nepal: A mixed-methods study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018; 29:95-102. [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2017.11.012] [PMID]

- Yeates N. The globalization of nurse migration: Policy issues and responses. Int Labour Rev. 2010; 149(4):423-40. [DOI:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2010.00096.x]

- Oda H, Tsujita Y, Irudaya Rajan S. An analysis of factors influencing the international migration of Indian nurses. J Int Migr Integr. 2018; 19(3):607-24. [DOI:10.1007/s12134-018-0548-2]

- APPG. Triple impact-how developing nursing will improve health, promote gender equality and support economic growth. London: APPG; 2016. [Link]

- Ramos P, Alves H. Migration intentions among Portuguese junior doctors: Results from a survey. Health Policy. 2017; 121(12):1208-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.09.016] [PMID]

- Kitt K, Gouda P, Evans DS, Goggin D, McGrath D, Last J, et al. Investigating the Irish brain drain: Factors influencing migration intentions among medical students. BMC Proceed. 2015; 9(7):A12. [DOI:10.1186/1753-6561-9-S7-A12]

- Suciu ŞM, Popescu CA, Ciumageanu MD, Buzoianu AD. Physician migration at its roots: A study on the emigration preferences and plans among medical students in Romania. Hum Resour Health. 2017; 15(1):6. [DOI:10.1186/s12960-017-0181-8] [PMID]

- Gouda P, Kitt K, Evans DS, Goggin D, McGrath D, Last J, et al. Ireland's medical brain drain: Migration intentions of Irish medical students. Hum Resour Health. 2015; 13:11. [DOI:10.1186/s12960-015-0003-9] [PMID]

- Ergin E, Akin B. Globalization and its Reflections for Health and Nursing. Int J Caring Sci. 2017; 10(1):607. [Link]

- Jones CB, Sherwood GD. The globalization of the nursing workforce: Pulling the pieces together. Nurs Outlook. 2014; 62(1):59-63. [DOI:10.1016/j.outlook.2013.12.005] [PMID]

- Yanardağ MZ, Yanardağ U, Avci Ö. Improvements which effect migration policies in the european :union: and turkey and a discussion of social work as a profession. Arch Health Sci Res. 2020; 7(1):95-103. [DOI:10.5152/ArcHealthSciRes.2020.597865]

- Tosunöz İK, Nazik E. Career future perceptions and attitudes towards migration of nursing students: A cross-sectional multicenter study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022; 63:103413. [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103413] [PMID]

- Hashish EA, Ashour HM. Determinants and mitigating factors of the brain drain among Egyptian nurses: A mixed-methods study. J Res Nurs. 2020; 25(8):699-719. [DOI:10.1177/1744987120940381] [PMID]

- Pung LX, Goh YS. Challenges faced by international nurses when migrating: An integrative literature review. Int Nurs Rev. 2017; 64(1):146-65. [DOI:10.1111/inr.12306] [PMID]

- Smith DM, Gillin N. Filipino nurse migration to the UK: Understanding migration choices from an ontological security-seeking perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2021; 276:113881. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113881] [PMID]

- Okafor C, Chimereze C. Brain drain among Nigerian nurses: Implications to the migrating nurse and the home country. Int J Res Sci Innov. 2020; 7(1):15-21. [Link]

- Silvestri DM, Blevins M, Afzal AR, Andrews B, Derbew M, Kaur S, et al. Medical and nursing students' intentions to work abroad or in rural areas: A cross-sectional survey in Asia and Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2014; 92(10):750-9. [DOI:10.2471/blt.14.136051] [PMID]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2024/12/18 | Accepted: 2025/09/8 | Published: 2025/09/8

Received: 2024/12/18 | Accepted: 2025/09/8 | Published: 2025/09/8

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |