Wed, Jan 28, 2026

Volume 36, Issue 1 (1-2026)

JHNM 2026, 36(1): 17-25 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Al Khutaba’a G, Ali T B, Bani Hani S, Bani Salameh F, Mahmoud Garaleah E. Nursing Students' Insulin Therapy Knowledge and Practices in Jordan. JHNM 2026; 36 (1) :17-25

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2454-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2454-en.html

Ghida’a Al Khutaba’a *1

, Tasneem Basheer Ali2

, Tasneem Basheer Ali2

, Salam Bani Hani3

, Salam Bani Hani3

, Fatima Bani Salameh4

, Fatima Bani Salameh4

, Ehoud Mahmoud Garaleah5

, Ehoud Mahmoud Garaleah5

, Tasneem Basheer Ali2

, Tasneem Basheer Ali2

, Salam Bani Hani3

, Salam Bani Hani3

, Fatima Bani Salameh4

, Fatima Bani Salameh4

, Ehoud Mahmoud Garaleah5

, Ehoud Mahmoud Garaleah5

1- Nursing (MSN), Department of Allied Medical Sciences, Karak University College, Al-Balqa Applied University, Karak, Jordan. , gkhataba@bau.edu.jo

2- Clinical Pharmacist (MSc), Department of Allied Medical Sciences, Karak University College, Al-Balqa Applied University, Karak, Jordan.

3- Assistant professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing, Irbid National University, Irbid, Jordan.

4- Clinical Pharmacist (MSc), Department of Adult Health Nursing, School of Nursing, Al-Albayt University, Mafraq, Jordan.

5- Nursing (MSN), Lecturer, Department of Allied Medical Sciences, Karak University College, Al-Balqa Applied University, Karak, Jordan.

2- Clinical Pharmacist (MSc), Department of Allied Medical Sciences, Karak University College, Al-Balqa Applied University, Karak, Jordan.

3- Assistant professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing, Irbid National University, Irbid, Jordan.

4- Clinical Pharmacist (MSc), Department of Adult Health Nursing, School of Nursing, Al-Albayt University, Mafraq, Jordan.

5- Nursing (MSN), Lecturer, Department of Allied Medical Sciences, Karak University College, Al-Balqa Applied University, Karak, Jordan.

Full-Text [PDF 488 kb]

(46 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (138 Views)

References

Full-Text: (4 Views)

Introduction

Persistent hyperglycemia and abnormalities in fat, protein, and carbohydrate metabolism are the main characteristics of diabetes mellitus (DM) [1]. These abnormalities arise from insulin resistance, inadequate insulin secretion, or a combination of both [2]. Globally, DM is among the most prevalent chronic diseases and poses a major public health challenge [3]. It occurs when the body is unable to produce sufficient insulin or cannot utilize it effectively, leading to consistently elevated blood glucose levels and subsequent long-term complications. These metabolic disorders also affect the way the body processes fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, underscoring the importance of understanding disease mechanisms to improve prevention and management strategies. The two most common types of DM are type 1 and type 2. Type 1 DM involves an absolute deficiency of insulin, whereas type 2 DM results from insulin resistance and relative insulin insufficiency [2]. Insulin therapy remains essential for diabetes management; it is the cornerstone treatment for type 1 DM and is frequently required to achieve optimal glycemic control in type 2 DM [4]. Proper insulin injection techniques are essential for achieving effective glycemic control in individuals with DM [5]. Inadequate or improper injection practices may lead to complications such as subcutaneous fat hypertrophy, lipoatrophy, and injection-site pain, all of which can negatively affect insulin absorption and subsequently disrupt blood glucose regulation [6]. According to Yu et al., nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice play a significant role in ensuring the safety and effectiveness of insulin administration [7]. Insulin formulations vary in their onset and duration of action and are classified as rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, or long-acting [8, 9]. In addition, multiple delivery devices—including syringes, insulin pens, and insulin pumps—require proper handling, storage, and administration techniques to ensure both therapeutic safety and clinical efficacy [10-12].

Insulin is among the most commonly prescribed medications in hospitals; however, it is also one of the most potentially harmful when administered incorrectly [13]. Mastering correct insulin administration is therefore a core clinical competency that nursing students must acquire during their academic and clinical training [14]. Adequate knowledge regarding insulin therapy—including its preparation, storage, and administration—is essential for improving diabetes management, enhancing patients’ Quality of Life (QoL), and reducing complications and treatment non-adherence [15, 16]. In Jordan, previous research assessing DM-related knowledge among registered nurses reported notable gaps in both knowledge and practice [17]. Continuous professional education remains a key requirement for maintaining competence in the management of complex conditions such as DM. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess nursing students’ knowledge and practices regarding insulin therapy in Jordan.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study. The study population consisted of all undergraduate nursing students enrolled at Jordanian universities in the academic year of 2024. Students who were willing to participate in the study and were eligible were included. Participants were required to be able to read and understand English (as the questionnaire was presented in English). Students not currently studying nursing and those with incomplete questionnaires were excluded. The sample size was calculated using the RaoSoft online calculator, considering a 5% margin of error, 95% confidence interval (CI), and an assumed response rate of 50% [18]. The estimated minimum sample size was 380. However, to account for potential sample dropout, 500 nursing students were recruited. All participants provided written informed consent before participation. All responses were anonymous and used solely for research purposes.

Data were collected using an online self-administered questionnaire over two months, from June to August 2024. The questionnaire was prepared electronically using Google Forms to ensure accessibility and convenience for participants. The survey link was distributed through social media applications such as Facebook and WhatsApp. The questionnaire was developed following an extensive review of previous literature on similar studies [5, 6, 8-16]. It consisted of three main sections with both open-ended and closed-ended questions. The demographic section collected data on age, sex, academic year, university, employment status, and DM-related experiences. The knowledge section comprised 18 items evaluating insulin therapy knowledge, including knowledge of indications, types, administration routes, side effects, complications, and storage conditions [8-13]. Each answer was scored as 1 point if correctly answered, and 0 points if incorrectly answered. Two items had multiple correct responses. The total score of this section ranged from 0 to 20 and was categorized as: poor knowledge (a score <8), moderate knowledge (score 9–15), excellent knowledge (score 16–20). The practice section had 9 items assessing students’ performance in insulin administration [5, 6, 12, 13]. Responses were scored as 1=correct answer, 0=incorrect answer, with a total possible score of 0–9, categorized as: Poor practice (score <4) and good practice (score 5–9).

The questionnaire’s face validity and content validity were assessed by a panel of experts (n=5) in nursing and pharmacology who evaluated the items for clarity, relevance, and appropriateness. A pilot study was conducted on 10 nursing students (not from the study participants) to assess comprehensibility and ease of completion. Based on feedback, minor wording adjustments were made. Based on their evaluations, the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) was calculated for each item using the Lawshe method, yielding an overall CVR of 0.84, while the Content Validity Index (CVI) for the entire tool was 0.89, indicating strong content validity. For testing reliability, a pilot study was conducted on 10 nursing students (not from the study participants) to assess clarity and internal consistency. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the overall scale was 0.73, with values of 0.78 for the knowledge subscale and 0.70 for the practice subscale, reflecting acceptable and internal consistency for both sections [19, 20].

The collected data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (Mean±SD, frequency, and percentage) were used to present demographic variables. Inferential statistics were applied to assess the associations between variables. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify the predictors of knowledge levels. Binary logistic regression examined the predictors of practice levels. P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

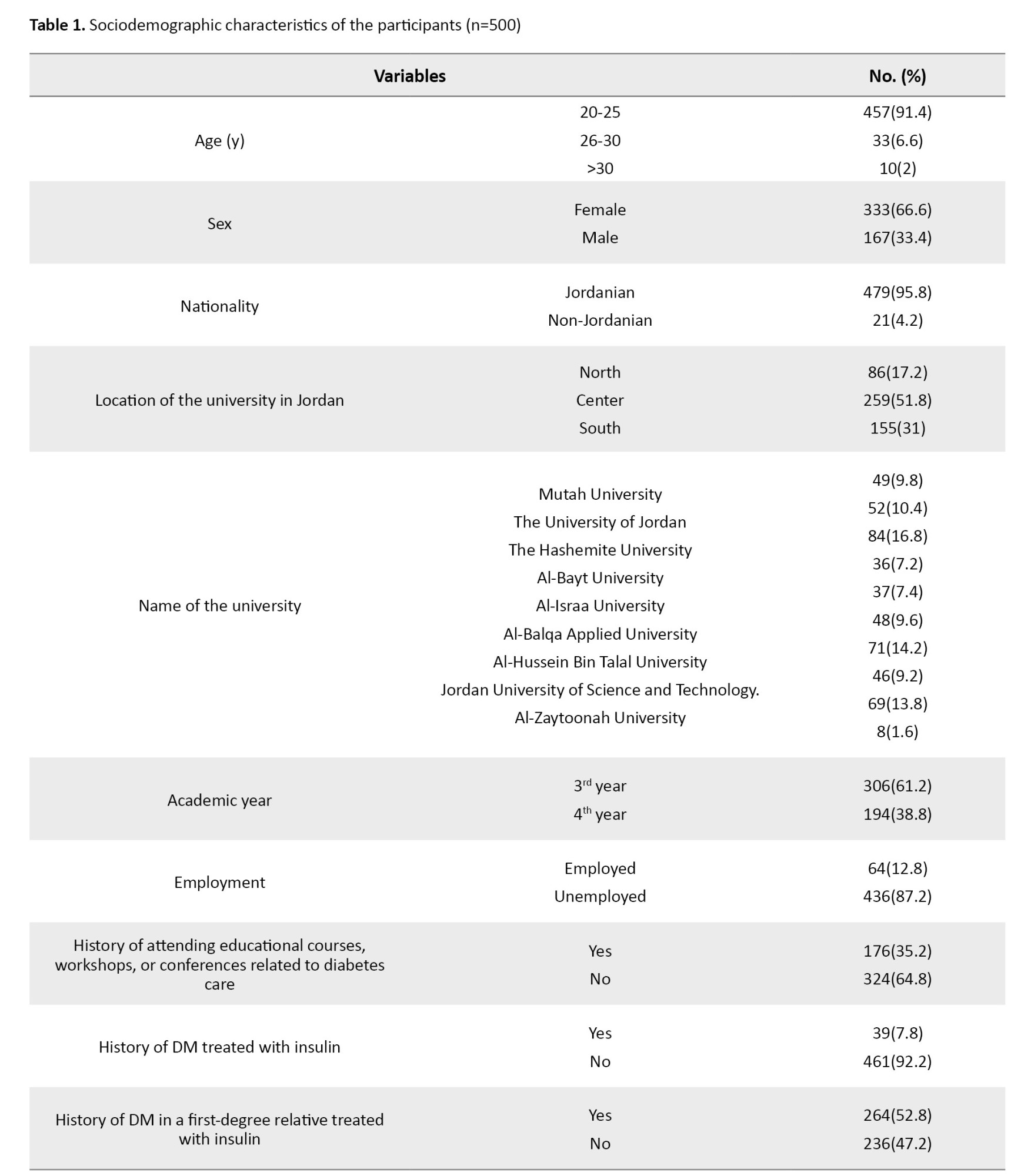

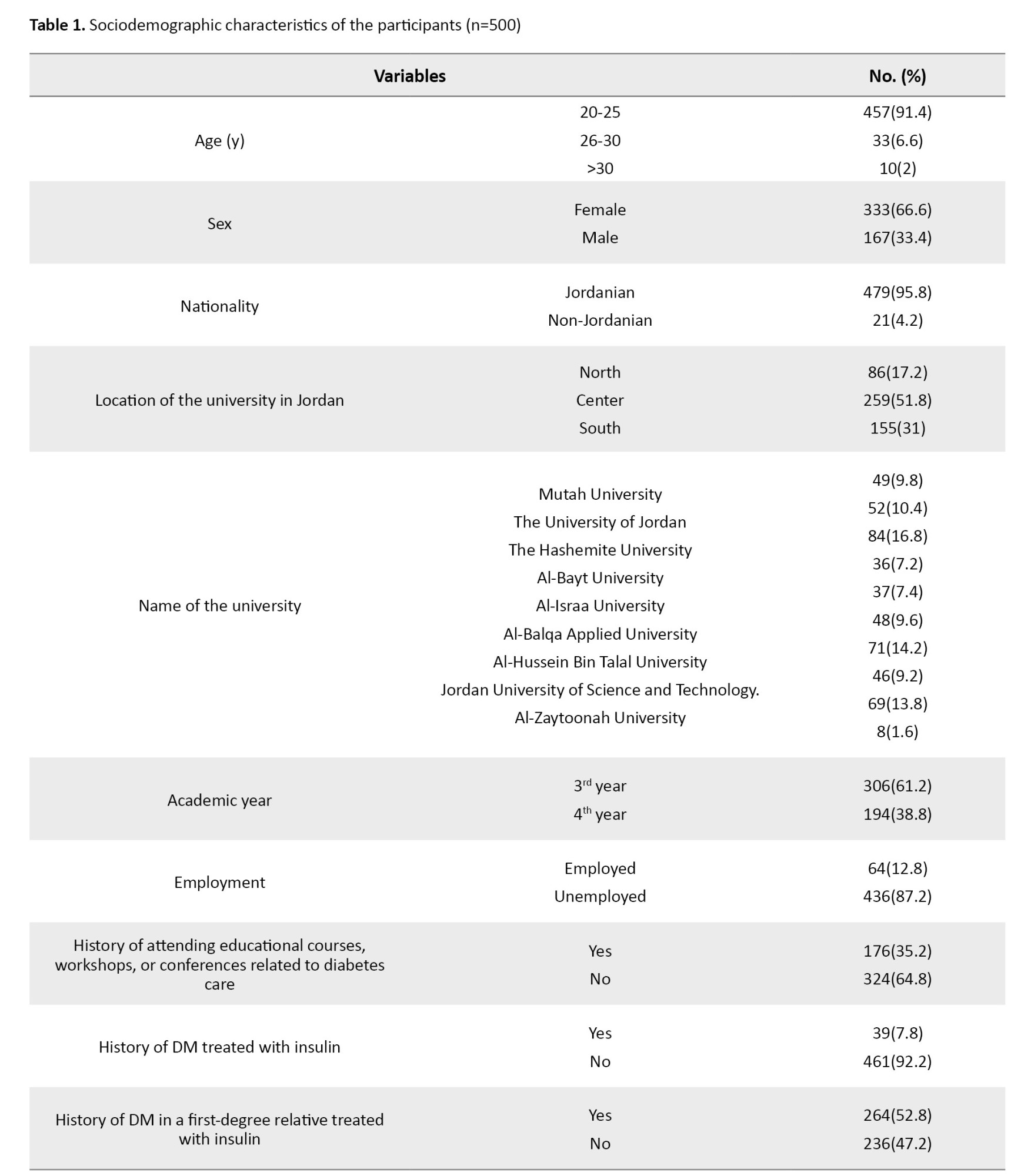

A total of 500 nursing students participated in the study. The majority were female (66.6%) and aged 20-25 years (91.4%). Most participants were Jordanian (95.8%), and more than half studied at universities located in the central region of Jordan (51.8%). Regarding academic year, 61.2% of students were in their third year, while 38.8% were in their fourth year. The majority were unemployed (87.2%), and approximately two-thirds (64.8%) had not attended any DM-related courses, workshops, or conferences. Only 7.8% reported having DM treated with insulin, while 52.8% had a first-degree relative with DM treated with insulin (Table 1).

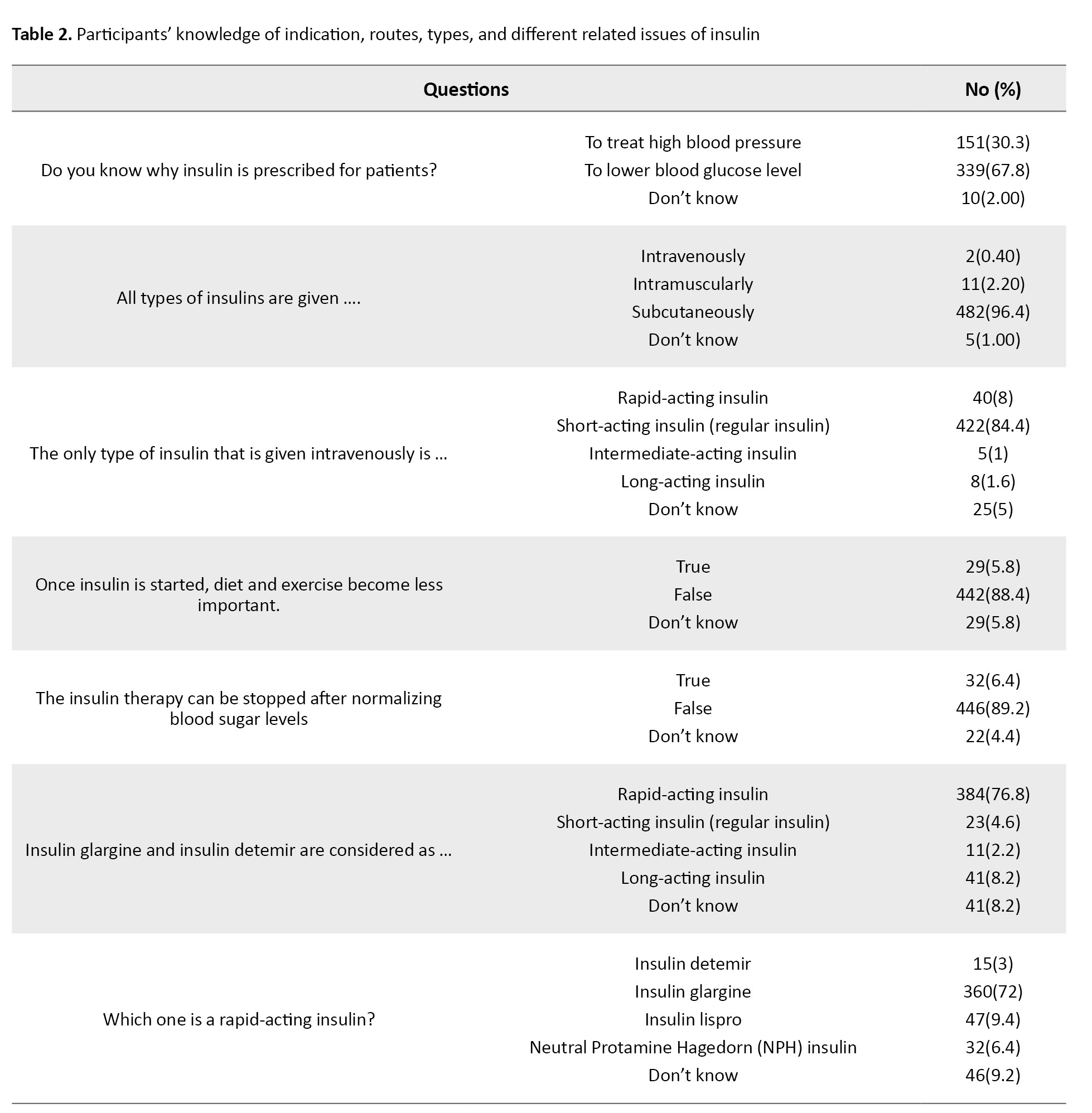

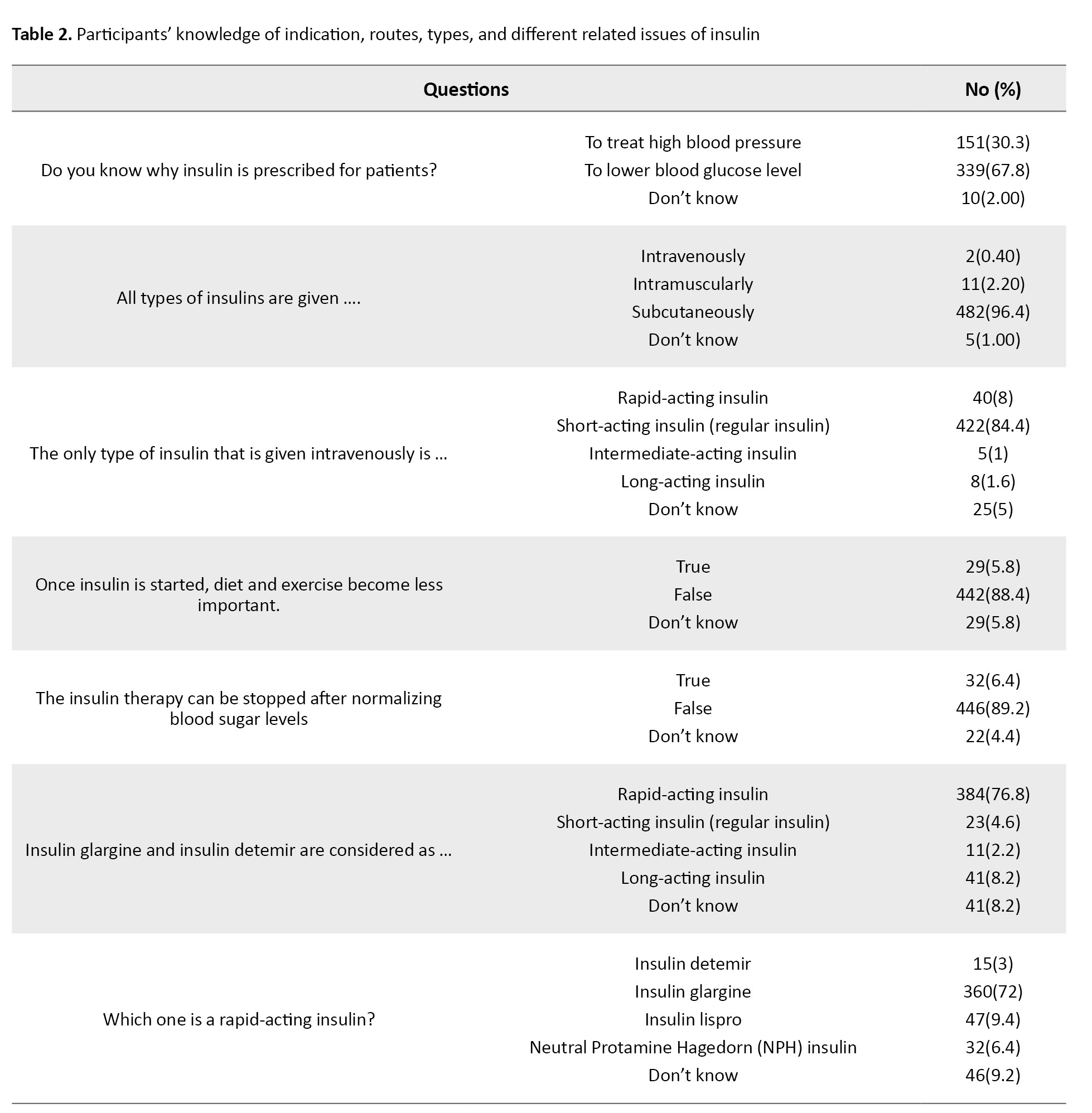

The mean knowledge score was 12.6±2.84, out of 20. Most participants (84.4%) demonstrated a moderate level of knowledge, 5% had poor knowledge, and 10.6% had excellent knowledge. Participants showed good knowledge of basic insulin concepts. Approximately two-thirds (67.8%) correctly identified insulin as prescribed to lower blood glucose, whereas 30.3% incorrectly believed that it is for hypertension. Almost all participants correctly indicated that insulin is administered subcutaneously (96.4%) and that short-acting insulin can be given intravenously (84.4%). These results are shown in Table 2.

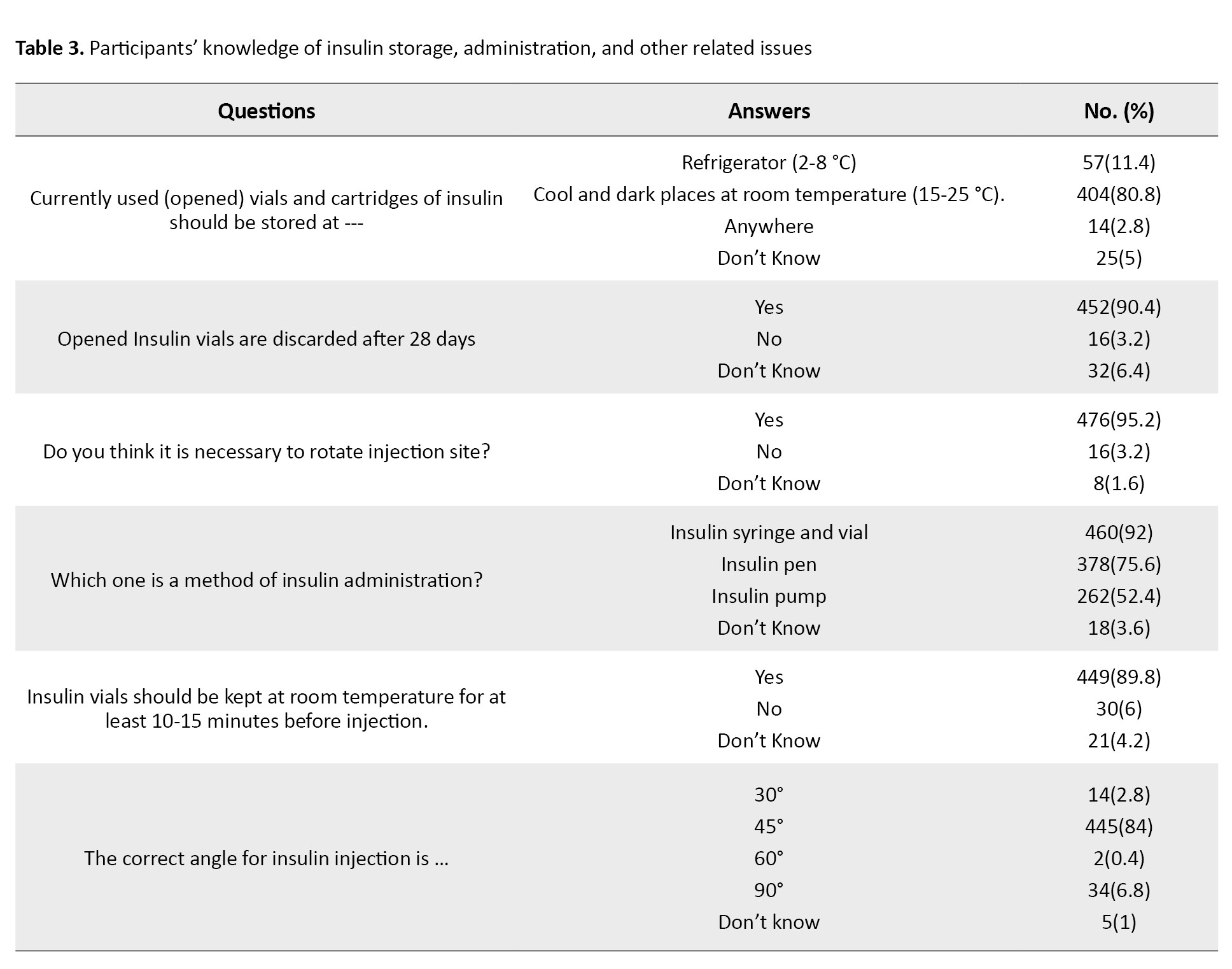

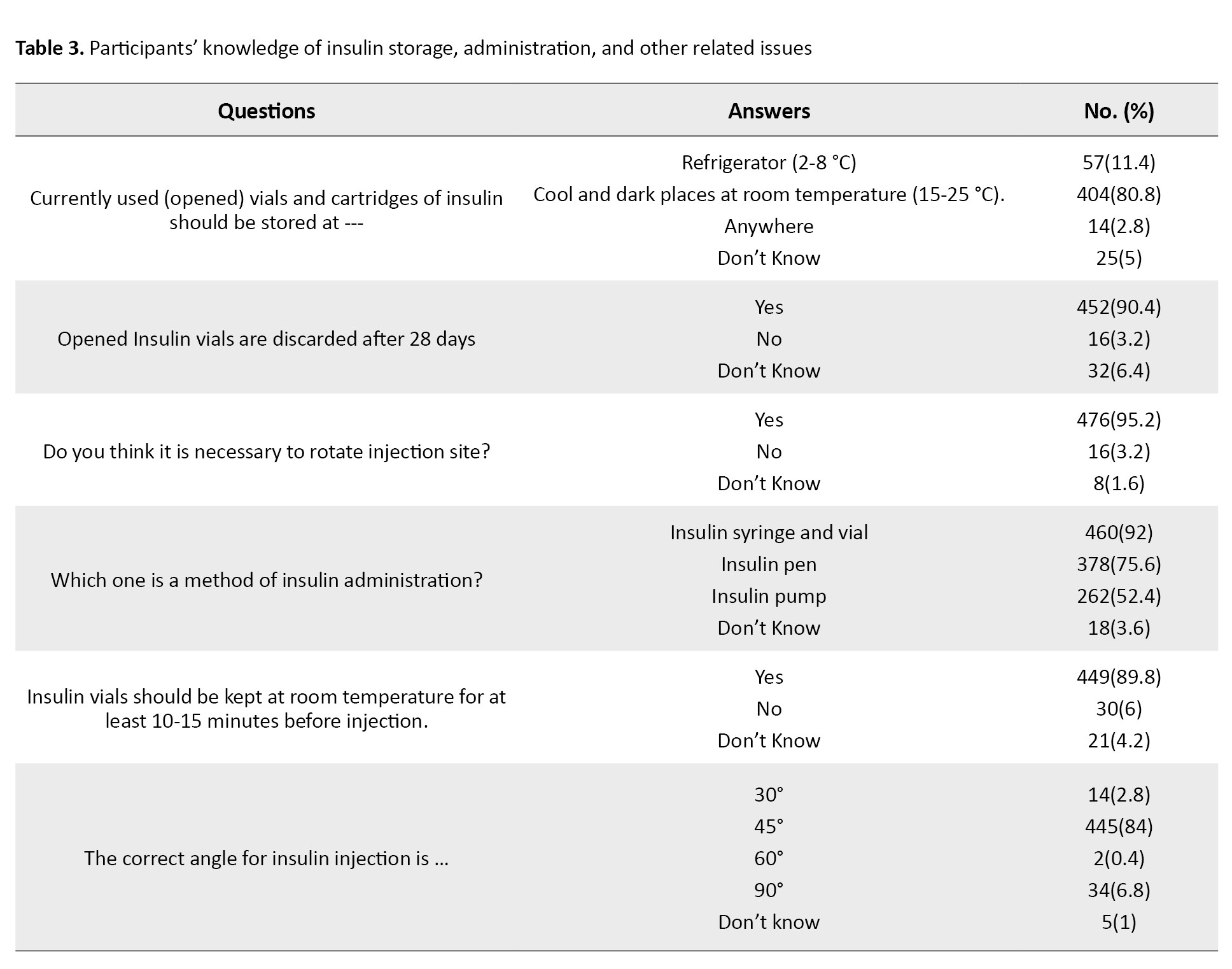

Regarding the knowledge of insulin storage, 80.8% correctly stated that opened insulin vials should be kept in a cool, dark place at room temperature (15–25 °C), and 90.4% knew they should be discarded after 28 days. Nearly all participants (99%) identified the abdomen as one of the preferred injection sites, while approximately half mentioned the upper arm (51.6%) and thigh (44.2%). Most participants knew that insulin should be kept at room temperature for 10–15 minutes before injection (89.8%) and that the appropriate injection angle is 45° (84%). These results are shown in Table 3.

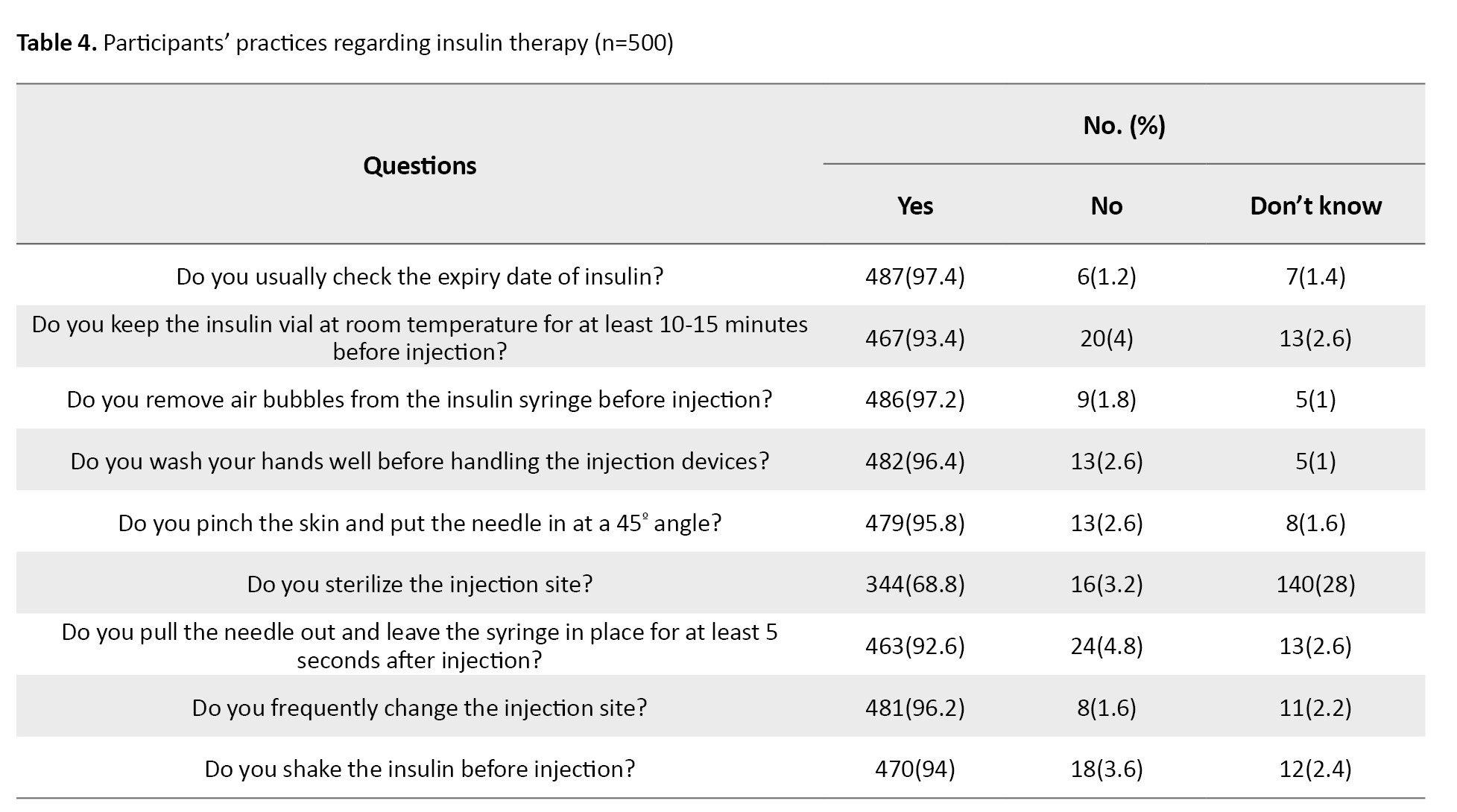

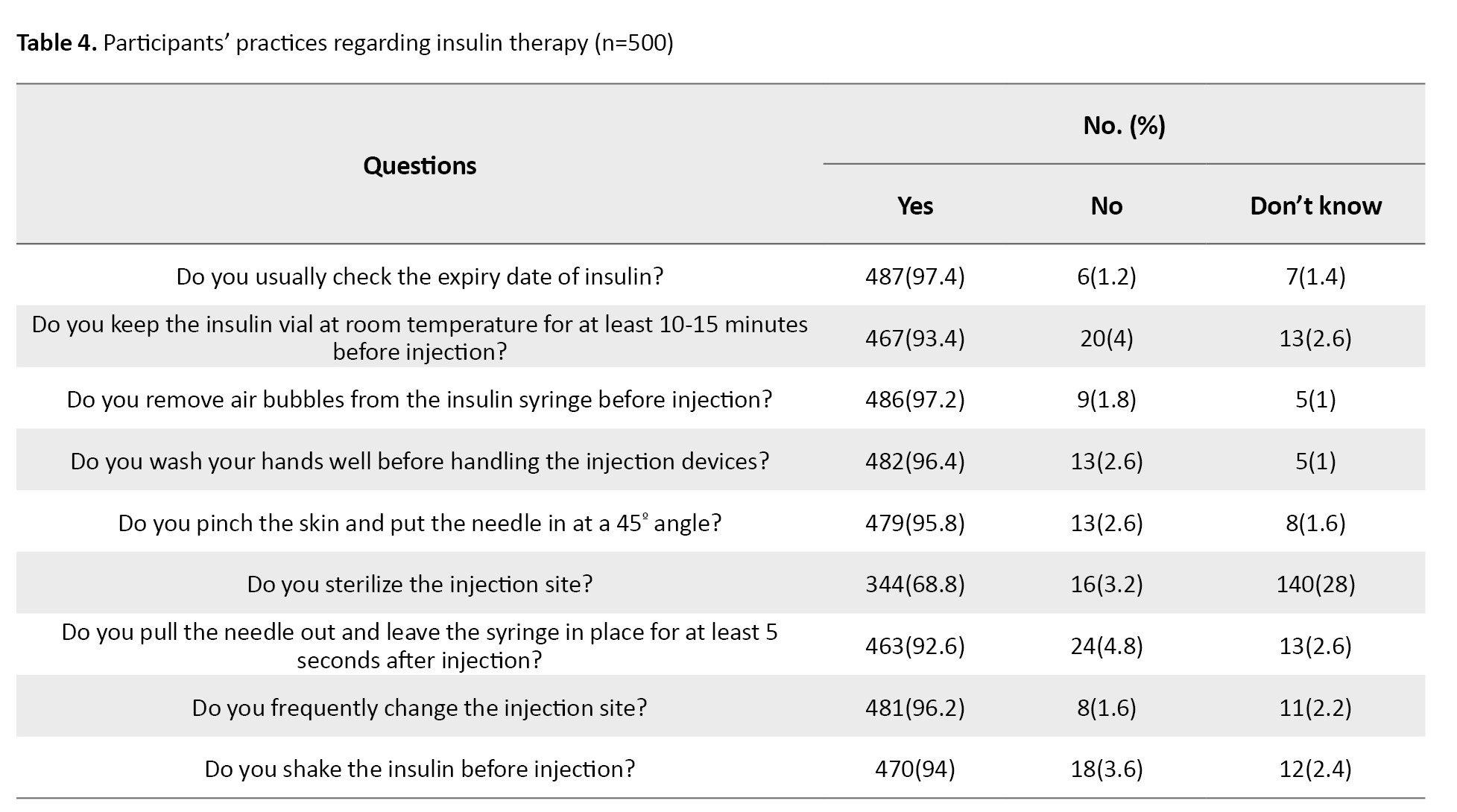

The mean practice score was 8.32±1.35 out of 9, indicating a high performance. A large majority (97%) demonstrated good practice, while only 3% showed poor practice. Most students consistently checked insulin expiry dates (97.4%), allowed vials to reach room temperature before injection (93.4%), removed air bubbles before injection (97.2%), washed hands before handling injection devices (96.4%), and rotated injection sites regularly (96.2%). However, fewer students routinely sterilized the injection site (68.8%), and 28% were uncertain about its necessity. These results are shown in Table 4.

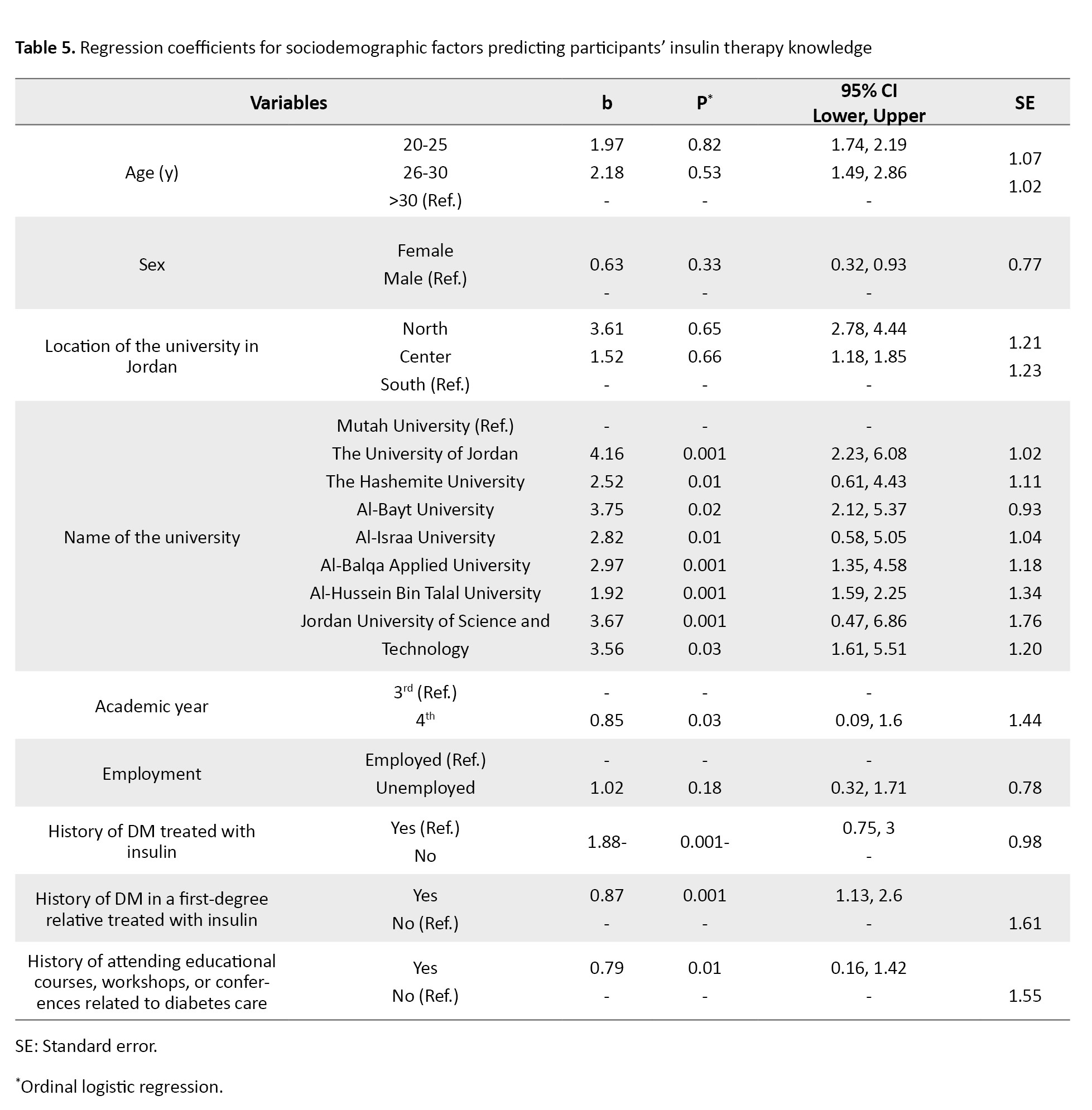

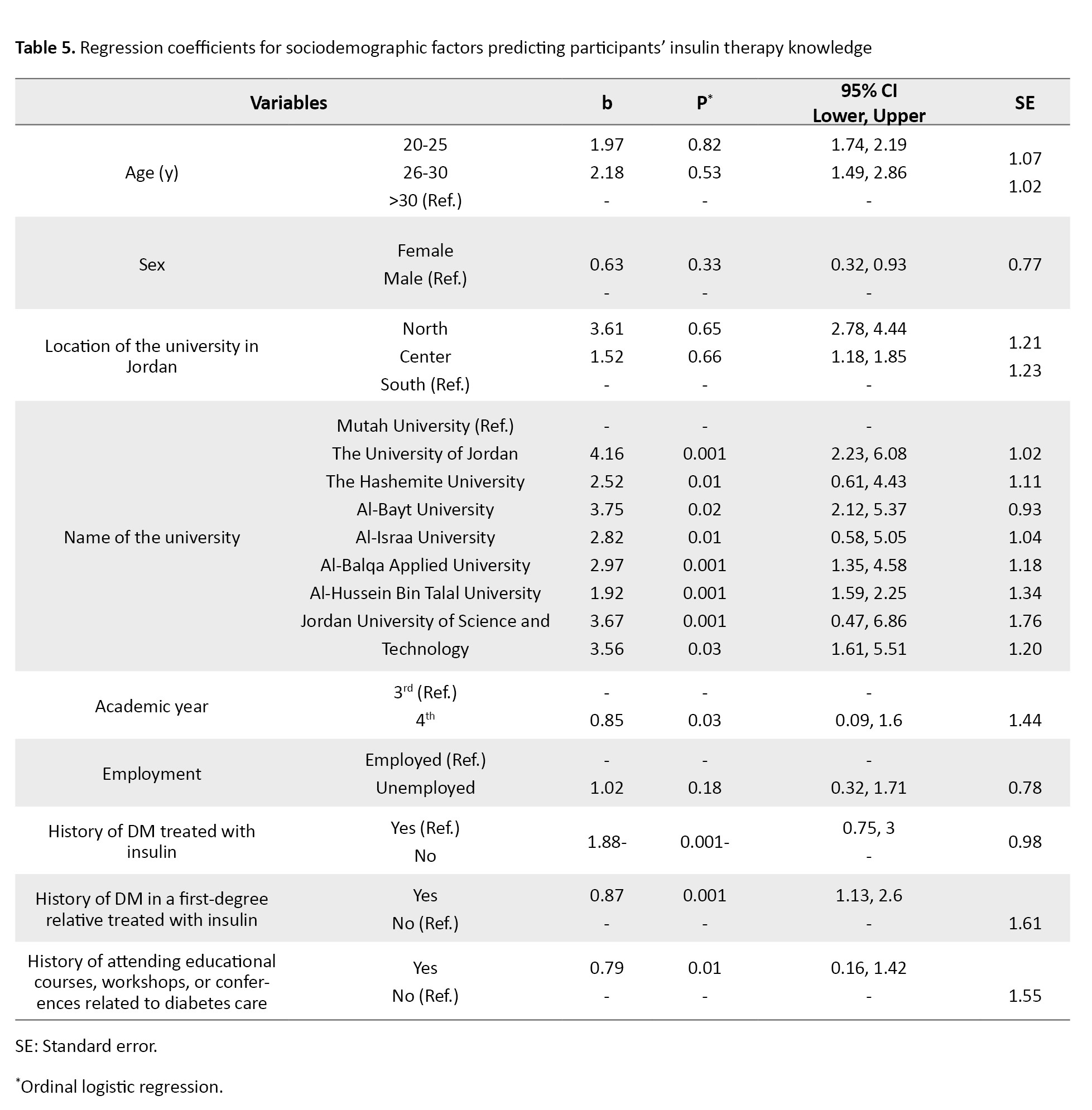

The ordinal logistic regression model identified several significant predictors of knowledge levels, as shown in Table 5.

Students’ university name was significantly associated with knowledge scores (P<0.001). For example, education in Al-Hussein Bin Talal University was significantly associated with higher knowledge compared to education in the Mutah University (b=1.92, 95% CI; 1.59%, 2.25%, P=0.001). The academic year was also a significant predictor (b=0.85, 95% CI; 0.09%, 1.6%, P=0.03). Being in the fourth academic year was associated with higher knowledge. Additionally, a history of DM treated with insulin was strongly associated with higher knowledge levels (b=1.88, 95% CI; 0.75%, 3%, P=0.001). Having a first-degree relative with a history of DM (b=0.87, 95% CI; 1.13%, 2.6%, P=0.001) and a history of attending diabetes-related educational courses or workshops (b=0.79, 95% CI; 0.16%, 1.42%, P=0.01) also had a significant association with knowledge scores. The binary logistic regression model showed that none of the sociodemographic characteristics had significant associations with the practice scores.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that Jordanian nursing students had varying levels of knowledge about insulin therapy, a cornerstone of diabetes management. While many students had a good knowledge of basic insulin concepts, noticeable gaps existed in more complex areas such as insulin classification, side effects, and dosage control. These findings are consistent with previous studies [20, 21], which reported inadequate knowledge and practice among nursing students and nurses. Both studies emphasized the importance of training programs and regular competency evaluations to enhance nurses’ skills in insulin therapy. Furthermore, our findings are in line with previous studies in Middle Eastern countries, which found that nursing students often have a low knowledge of DM care and insulin administration. For example, a study in Saudi Arabia reported that DM-related materials were insufficiently integrated into nursing curricula [22]. Therefore, diabetes management education should be comprehensively integrated into nursing courses and should achieve higher levels of proficiency among students. There is also a need to improve nursing curricula in Jordan to strengthen theoretical and practical DM education.

In the current study, significant associations were observed between students’ knowledge scores and their university, academic year, history of DM in the students or their families, and participation in DM-related educational courses or workshops. These findings align with those of Alsolais et al., who reported that academic level, university affiliation, and direct experience with diabetic patients were significant predictors of students’ knowledge [22]. These findings underscore the value of experiential learning and targeted education in enhancing competency levels. The sex factor showed no significant association with knowledge or practice of insulin therapy, contrary to Wu et al.’s findings [20]. This may indicate that nursing education programs in Jordan provide equitable opportunities for both male and female students to acquire similar levels of theoretical and practical competence. However, there is still a need for more structured educational interventions to bridge remaining knowledge gaps. The association between high academic year and knowledge scores suggests that nursing students’ knowledge of insulin therapy improves as they progress academically. This observation supports earlier findings that nurses with advanced education and greater clinical experience have more comprehensive knowledge of diabetes management, pharmacology, and insulin therapy [23]. Such nurses are also better able to educate patients, recognize adverse effects, and safely adjust insulin doses in collaboration with healthcare teams.

Overall, the results highlight an urgent need to enhance the DM-related educational materials within Jordanian nursing curricula. Specifically, nursing schools should incorporate hands-on training, simulation exercises, and case-based learning focused on insulin therapy. These interventions can enhance nursing students’ confidence and competence in insulin administration, leading to safer and more effective diabetes management in clinical practice. As future healthcare professionals, well-trained nursing students are key to ensuring effective glycemic control, minimizing insulin-related errors, and improving the overall quality of diabetic care [4, 21, 16, 11].

This study had some limitations. Its cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of causal relationships between variables. The samples were limited to nursing students from selected Jordanian universities, which may restrict the generalizability of findings to all nursing students in the country. Moreover, since the data were self-reported, participants may have over- or underestimated their knowledge and practices, introducing potential response bias. Future studies should employ longitudinal or interventional designs to better assess the effectiveness of educational programs aimed at improving nursing students’ knowledge and practices regarding insulin therapy.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Al-Balqa Applied University, Karak, Jordan (Code: 26/3/2/2378). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Data collection and data analysis: Ghida’a Al Khutaba’a and Tasneem Basheer Ali; Draft preparation: Ghida’a Al Khutaba’a and Salam Bani Hani; Supervision: Ghida’a Al Khutaba’a, Fatima Bani Salama, and Ehoud Mahmoud Garaleah; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all nursing students who participated in this research for their time and cooperation.

Persistent hyperglycemia and abnormalities in fat, protein, and carbohydrate metabolism are the main characteristics of diabetes mellitus (DM) [1]. These abnormalities arise from insulin resistance, inadequate insulin secretion, or a combination of both [2]. Globally, DM is among the most prevalent chronic diseases and poses a major public health challenge [3]. It occurs when the body is unable to produce sufficient insulin or cannot utilize it effectively, leading to consistently elevated blood glucose levels and subsequent long-term complications. These metabolic disorders also affect the way the body processes fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, underscoring the importance of understanding disease mechanisms to improve prevention and management strategies. The two most common types of DM are type 1 and type 2. Type 1 DM involves an absolute deficiency of insulin, whereas type 2 DM results from insulin resistance and relative insulin insufficiency [2]. Insulin therapy remains essential for diabetes management; it is the cornerstone treatment for type 1 DM and is frequently required to achieve optimal glycemic control in type 2 DM [4]. Proper insulin injection techniques are essential for achieving effective glycemic control in individuals with DM [5]. Inadequate or improper injection practices may lead to complications such as subcutaneous fat hypertrophy, lipoatrophy, and injection-site pain, all of which can negatively affect insulin absorption and subsequently disrupt blood glucose regulation [6]. According to Yu et al., nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice play a significant role in ensuring the safety and effectiveness of insulin administration [7]. Insulin formulations vary in their onset and duration of action and are classified as rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, or long-acting [8, 9]. In addition, multiple delivery devices—including syringes, insulin pens, and insulin pumps—require proper handling, storage, and administration techniques to ensure both therapeutic safety and clinical efficacy [10-12].

Insulin is among the most commonly prescribed medications in hospitals; however, it is also one of the most potentially harmful when administered incorrectly [13]. Mastering correct insulin administration is therefore a core clinical competency that nursing students must acquire during their academic and clinical training [14]. Adequate knowledge regarding insulin therapy—including its preparation, storage, and administration—is essential for improving diabetes management, enhancing patients’ Quality of Life (QoL), and reducing complications and treatment non-adherence [15, 16]. In Jordan, previous research assessing DM-related knowledge among registered nurses reported notable gaps in both knowledge and practice [17]. Continuous professional education remains a key requirement for maintaining competence in the management of complex conditions such as DM. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess nursing students’ knowledge and practices regarding insulin therapy in Jordan.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study. The study population consisted of all undergraduate nursing students enrolled at Jordanian universities in the academic year of 2024. Students who were willing to participate in the study and were eligible were included. Participants were required to be able to read and understand English (as the questionnaire was presented in English). Students not currently studying nursing and those with incomplete questionnaires were excluded. The sample size was calculated using the RaoSoft online calculator, considering a 5% margin of error, 95% confidence interval (CI), and an assumed response rate of 50% [18]. The estimated minimum sample size was 380. However, to account for potential sample dropout, 500 nursing students were recruited. All participants provided written informed consent before participation. All responses were anonymous and used solely for research purposes.

Data were collected using an online self-administered questionnaire over two months, from June to August 2024. The questionnaire was prepared electronically using Google Forms to ensure accessibility and convenience for participants. The survey link was distributed through social media applications such as Facebook and WhatsApp. The questionnaire was developed following an extensive review of previous literature on similar studies [5, 6, 8-16]. It consisted of three main sections with both open-ended and closed-ended questions. The demographic section collected data on age, sex, academic year, university, employment status, and DM-related experiences. The knowledge section comprised 18 items evaluating insulin therapy knowledge, including knowledge of indications, types, administration routes, side effects, complications, and storage conditions [8-13]. Each answer was scored as 1 point if correctly answered, and 0 points if incorrectly answered. Two items had multiple correct responses. The total score of this section ranged from 0 to 20 and was categorized as: poor knowledge (a score <8), moderate knowledge (score 9–15), excellent knowledge (score 16–20). The practice section had 9 items assessing students’ performance in insulin administration [5, 6, 12, 13]. Responses were scored as 1=correct answer, 0=incorrect answer, with a total possible score of 0–9, categorized as: Poor practice (score <4) and good practice (score 5–9).

The questionnaire’s face validity and content validity were assessed by a panel of experts (n=5) in nursing and pharmacology who evaluated the items for clarity, relevance, and appropriateness. A pilot study was conducted on 10 nursing students (not from the study participants) to assess comprehensibility and ease of completion. Based on feedback, minor wording adjustments were made. Based on their evaluations, the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) was calculated for each item using the Lawshe method, yielding an overall CVR of 0.84, while the Content Validity Index (CVI) for the entire tool was 0.89, indicating strong content validity. For testing reliability, a pilot study was conducted on 10 nursing students (not from the study participants) to assess clarity and internal consistency. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the overall scale was 0.73, with values of 0.78 for the knowledge subscale and 0.70 for the practice subscale, reflecting acceptable and internal consistency for both sections [19, 20].

The collected data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (Mean±SD, frequency, and percentage) were used to present demographic variables. Inferential statistics were applied to assess the associations between variables. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify the predictors of knowledge levels. Binary logistic regression examined the predictors of practice levels. P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 500 nursing students participated in the study. The majority were female (66.6%) and aged 20-25 years (91.4%). Most participants were Jordanian (95.8%), and more than half studied at universities located in the central region of Jordan (51.8%). Regarding academic year, 61.2% of students were in their third year, while 38.8% were in their fourth year. The majority were unemployed (87.2%), and approximately two-thirds (64.8%) had not attended any DM-related courses, workshops, or conferences. Only 7.8% reported having DM treated with insulin, while 52.8% had a first-degree relative with DM treated with insulin (Table 1).

The mean knowledge score was 12.6±2.84, out of 20. Most participants (84.4%) demonstrated a moderate level of knowledge, 5% had poor knowledge, and 10.6% had excellent knowledge. Participants showed good knowledge of basic insulin concepts. Approximately two-thirds (67.8%) correctly identified insulin as prescribed to lower blood glucose, whereas 30.3% incorrectly believed that it is for hypertension. Almost all participants correctly indicated that insulin is administered subcutaneously (96.4%) and that short-acting insulin can be given intravenously (84.4%). These results are shown in Table 2.

Regarding the knowledge of insulin storage, 80.8% correctly stated that opened insulin vials should be kept in a cool, dark place at room temperature (15–25 °C), and 90.4% knew they should be discarded after 28 days. Nearly all participants (99%) identified the abdomen as one of the preferred injection sites, while approximately half mentioned the upper arm (51.6%) and thigh (44.2%). Most participants knew that insulin should be kept at room temperature for 10–15 minutes before injection (89.8%) and that the appropriate injection angle is 45° (84%). These results are shown in Table 3.

The mean practice score was 8.32±1.35 out of 9, indicating a high performance. A large majority (97%) demonstrated good practice, while only 3% showed poor practice. Most students consistently checked insulin expiry dates (97.4%), allowed vials to reach room temperature before injection (93.4%), removed air bubbles before injection (97.2%), washed hands before handling injection devices (96.4%), and rotated injection sites regularly (96.2%). However, fewer students routinely sterilized the injection site (68.8%), and 28% were uncertain about its necessity. These results are shown in Table 4.

The ordinal logistic regression model identified several significant predictors of knowledge levels, as shown in Table 5.

Students’ university name was significantly associated with knowledge scores (P<0.001). For example, education in Al-Hussein Bin Talal University was significantly associated with higher knowledge compared to education in the Mutah University (b=1.92, 95% CI; 1.59%, 2.25%, P=0.001). The academic year was also a significant predictor (b=0.85, 95% CI; 0.09%, 1.6%, P=0.03). Being in the fourth academic year was associated with higher knowledge. Additionally, a history of DM treated with insulin was strongly associated with higher knowledge levels (b=1.88, 95% CI; 0.75%, 3%, P=0.001). Having a first-degree relative with a history of DM (b=0.87, 95% CI; 1.13%, 2.6%, P=0.001) and a history of attending diabetes-related educational courses or workshops (b=0.79, 95% CI; 0.16%, 1.42%, P=0.01) also had a significant association with knowledge scores. The binary logistic regression model showed that none of the sociodemographic characteristics had significant associations with the practice scores.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that Jordanian nursing students had varying levels of knowledge about insulin therapy, a cornerstone of diabetes management. While many students had a good knowledge of basic insulin concepts, noticeable gaps existed in more complex areas such as insulin classification, side effects, and dosage control. These findings are consistent with previous studies [20, 21], which reported inadequate knowledge and practice among nursing students and nurses. Both studies emphasized the importance of training programs and regular competency evaluations to enhance nurses’ skills in insulin therapy. Furthermore, our findings are in line with previous studies in Middle Eastern countries, which found that nursing students often have a low knowledge of DM care and insulin administration. For example, a study in Saudi Arabia reported that DM-related materials were insufficiently integrated into nursing curricula [22]. Therefore, diabetes management education should be comprehensively integrated into nursing courses and should achieve higher levels of proficiency among students. There is also a need to improve nursing curricula in Jordan to strengthen theoretical and practical DM education.

In the current study, significant associations were observed between students’ knowledge scores and their university, academic year, history of DM in the students or their families, and participation in DM-related educational courses or workshops. These findings align with those of Alsolais et al., who reported that academic level, university affiliation, and direct experience with diabetic patients were significant predictors of students’ knowledge [22]. These findings underscore the value of experiential learning and targeted education in enhancing competency levels. The sex factor showed no significant association with knowledge or practice of insulin therapy, contrary to Wu et al.’s findings [20]. This may indicate that nursing education programs in Jordan provide equitable opportunities for both male and female students to acquire similar levels of theoretical and practical competence. However, there is still a need for more structured educational interventions to bridge remaining knowledge gaps. The association between high academic year and knowledge scores suggests that nursing students’ knowledge of insulin therapy improves as they progress academically. This observation supports earlier findings that nurses with advanced education and greater clinical experience have more comprehensive knowledge of diabetes management, pharmacology, and insulin therapy [23]. Such nurses are also better able to educate patients, recognize adverse effects, and safely adjust insulin doses in collaboration with healthcare teams.

Overall, the results highlight an urgent need to enhance the DM-related educational materials within Jordanian nursing curricula. Specifically, nursing schools should incorporate hands-on training, simulation exercises, and case-based learning focused on insulin therapy. These interventions can enhance nursing students’ confidence and competence in insulin administration, leading to safer and more effective diabetes management in clinical practice. As future healthcare professionals, well-trained nursing students are key to ensuring effective glycemic control, minimizing insulin-related errors, and improving the overall quality of diabetic care [4, 21, 16, 11].

This study had some limitations. Its cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of causal relationships between variables. The samples were limited to nursing students from selected Jordanian universities, which may restrict the generalizability of findings to all nursing students in the country. Moreover, since the data were self-reported, participants may have over- or underestimated their knowledge and practices, introducing potential response bias. Future studies should employ longitudinal or interventional designs to better assess the effectiveness of educational programs aimed at improving nursing students’ knowledge and practices regarding insulin therapy.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Al-Balqa Applied University, Karak, Jordan (Code: 26/3/2/2378). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Data collection and data analysis: Ghida’a Al Khutaba’a and Tasneem Basheer Ali; Draft preparation: Ghida’a Al Khutaba’a and Salam Bani Hani; Supervision: Ghida’a Al Khutaba’a, Fatima Bani Salama, and Ehoud Mahmoud Garaleah; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all nursing students who participated in this research for their time and cooperation.

References

- Dilworth L, Facey A, Omoruyi F. Diabetes mellitus and its metabolic complications: The role of adipose tissues. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22(14):7644. [DOI:10.3390/ijms22147644] [PMID]

- Kumar R, Saha P, Kumar Y, Sahana S, Dubey A, Prakash O. A review on diabetes mellitus: Type 1 & type 2. World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2020; 9(10):838-50. [Link]

- Abouzid MR, Ali K, Elkhawas I, Elshafei SM. An overview of diabetes mellitus in Egypt and the significance of integrating preventive cardiology in diabetes management. Cureus. 2022; 14(7):e26791. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.27066]

- Dwivedi M, Pandey AR. Diabetes mellitus and its treatment: An overview. J Adv Pharmacol. 2020; 1(1):48-58. [Link]

- Bari B, Corbeil MA, Farooqui H, Menzies S, Pflug B, Smith BK, et al. Insulin injection practices in a population of Canadians with diabetes: An observational study. Diabetes Ther. 2020; 11(11):2595-609.[DOI:10.1007/s13300-020-00913-y] [PMID]

- Kamrul-Hasan A, Paul AK, Amin MN, Gaffar MAJ, Asaduzzaman M, Saifuddin M, et al. Insulin injection practice and injection complications: results from the Bangladesh insulin injection technique survey. Eur Endocrinol. 2020; 16(1):41-8. [DOI:10.17925/EE.2020.16.1.41] [PMID]

- Yu B, Li C, Sun Y, Wang DW. Insulin treatment is associated with increased mortality in patients with COVID-19 and type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2021; 33(1):65-77.e2. [DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2020.11.014] [PMID]

- Alnaim L, Altuwaym RA, Aldehan SM, Alquraishi NM. Assessment of knowledge among caregivers of diabetic patients in insulin dosage regimen and administration. Saudi Pharm J. 2021; 29(10):1137-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsps.2021.08.010] [PMID]

- Silver B, Ramaiya K, Andrew SB, Fredrick O, Bajaj S, Kalra S, et al. EADSG guidelines: Insulin therapy in diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2018; 9(2):449-92. [DOI:10.1007/s13300-018-0384-6] [PMID]

- Cunha GHD, Fontenele MSM, Siqueira LR, Lima MAC, Gomes MEC, Ramalho AKL. Insulin therapy practice performed by people with diabetes in primary healthcare. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2020; 54:e03620. [DOI:10.1590/s1980-220x2019002903620] [PMID]

- Galdón Sanz-Pastor A, Justel Enríquez A, Sánchez Bao A, Ampudia-Blasco FJ. Current barriers to initiating insulin therapy in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024; 15:1366368. [DOI:10.3389/fendo.2024.1366368] [PMID]

- Yasmin S, Raveendran AV, Jayakrishnan B, Sreelakshmi R, Jose R, Chandran V, et al. How common are the errors in insulin injection techniques: A real-world study. Int J Diabetes Technol. 2023; 2(4):109-11. [DOI:10.4103/ijdt.ijdt_7_24]

- Mukherjee JJ, Rajput R, Majumdar S, Saboo B, Chatterjee S. Practical aspects of insulin use in India: Descriptive review and key recommendations. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021; 15(3):937-48.[DOI:10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.018] [PMID]

- Bain A, Kavanagh S, McCarthy S, Babar Z. Assessment of insulin-related knowledge among healthcare professionals in a large teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. Pharmacy (Basel). 2019; 7(1):16. [DOI:10.3390/pharmacy7010016] [PMID]

- Nasir BB, Buseir MS, Muhammed OS. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards insulin self-administration and associated factors among diabetic patients at Zewditu Memorial Hospital, Ethiopia. Plos One. 2021; 16(2):e0246741. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0246741] [PMID]

- Yacoub MI, Demeh WM, Darawad MW, Barr JL, Saleh AM, Saleh MY. An assessment of diabetes-related knowledge among registered nurses working in hospitals in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev. 2014; 61(2):255-62. [DOI:10.1111/inr.12090] [PMID]

- Raosoft Inc. Sample size calculator. Seattle: Raosoft Inc; 2004. [Link]

- Hani SB, Saleh MY. Using a real-time, partially automated interactive system to interpret patients’ data for diabetic self-management: A rapid literature review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2023; 19(5):e311022210519. [DOI:10.2174/1573399819666221031161442] [PMID]

- Abdul-Ra’aoof HH, Tiryag AM, Atiyah MA. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of nursing students about insulin therapy: A cross-sectional study. Academia Open. 2024; 9(1):28795. [DOI:10.21070/acopen.9.2024.8795]

- Wu X, Zhao F, Zhang M, Yuan L, Zheng Y, Huang J, et al. Insulin injection knowledge, attitudes, and practices of nurses in China. Diabetes Ther. 2021; 12(6):2451-69. [DOI:10.1007/s13300-021-01122-x] [PMID]

- Khamaiseh A, Alshloul M. Diabetes knowledge among health sciences students in Saudi Arabia and Jordan. Jordan Med J. 2019; 53(1):37-48. [Link]

- Alsolais AM, Bajet JB, Alquwez N, Alotaibi KA, Almansour AM, Alshammari F, Cruz JP, Alotaibi JS. Predictors of self-assessed and actual knowledge about diabetes among nursing students in Saudi Arabia. J Person Med. 2023; 13(1):57. [DOI:0.3390/jpm13010057]

- Shather Hadi S, Kadhum Aljebore H, Abd Al-Hamza Marhoon A. Nurses’ knowledge and awareness regarding insulin therapy for diabetic patients in the emergency department at Al Diwaniyah Teaching Hospital. Med Clin Res. 2023; 8(8):1-7. [DOI:10.33140/MCR.08.08.03]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2024/12/2 | Accepted: 2025/03/29 | Published: 2026/01/11

Received: 2024/12/2 | Accepted: 2025/03/29 | Published: 2026/01/11

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |