Thu, Jan 29, 2026

Volume 34, Issue 4 (9-2024)

JHNM 2024, 34(4): 345-356 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Falahzade F, Yaghobi Y, Mirzaei M, Hosseinzadeh Siboni F, Kazemnezhad Leili E. Separation Anxiety and Its Related Factors Among Preschool Children in Northern Iran From the Parents’ Point of View. JHNM 2024; 34 (4) :345-356

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2319-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2319-en.html

Fatemeh Falahzade1

, Yasaman Yaghobi *2

, Yasaman Yaghobi *2

, Mahshid Mirzaei3

, Mahshid Mirzaei3

, Fatemeh Hosseinzadeh Siboni4

, Fatemeh Hosseinzadeh Siboni4

, Ehsan Kazemnezhad Leili5

, Ehsan Kazemnezhad Leili5

, Yasaman Yaghobi *2

, Yasaman Yaghobi *2

, Mahshid Mirzaei3

, Mahshid Mirzaei3

, Fatemeh Hosseinzadeh Siboni4

, Fatemeh Hosseinzadeh Siboni4

, Ehsan Kazemnezhad Leili5

, Ehsan Kazemnezhad Leili5

1- Nursing (MSN), Imam Ali Hospital, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Mazandaran, Iran.

2- Assistant Professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,yasamanyaghobi@yahoo.com

3- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- PhD. Candidate in Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

5- Associate Professor, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Assistant Professor, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,

3- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- PhD. Candidate in Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

5- Associate Professor, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 584 kb]

(749 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1058 Views)

Full-Text: (842 Views)

Introduction

Separation anxiety disorder (SAD) is one of the most common anxiety disorders in childhood. It refers to the exaggeration of developmentally normal anxiety when the child is unexpectedly separated from home or an attachment figure and enters a new neighborhood or school, death, or illness of close relatives [1, 2]. It is a normal phase of development in children aged 1-3 years [3]. Children normally experience some degree of fear, anxiety, or worry about seeing strangers, being alone, and facing new situations, from about six months to a few years before school [4]. Most of the identified cases of SAD have been in one-and-a-half-year-old children. Gradual improvement is expected at the age of 4-5 years [3, 5]. In Iran, the prevalence of SAD in children is 5.3% [6]. The presence of progressive SAD at older ages in children may indicate a risk of developing anxiety disorders. Persistence of SAD disrupts the child’s daily life and can lead to anxiety disorders [3]. It is also a predictor of psychiatric disorders in adolescence; if it is left untreated, it can cause the disorder to continue into adulthood [7]. Anxiety disorders are very important because of their high prevalence [8] and negative functional consequences [4]. According to studies, the prevalence of SAD in Iranian children and adolescents ranges from 0.7-15.7% [9].

Environmental factors [4], family/culture, maternal depression, maternal smoking during pregnancy, parental unemployment [5, 8], parental divorce [10], parenting styles, parental self-efficacy [11], parents’ educational level, parents’ age, place of residence, mother’s job [12], socioeconomic conditions, genetics [4], having a single parent, number of siblings [13], prenatal risk factors [3], severe family environmental stressors [14], socio-emotional behaviors of children, child age, and child gender [8]. have been mentioned as factors affecting childhood SAD. To manage this problem, structured, comprehensive training programs and interventions are needed [5]. In this regard, and due to the statistical heterogeneity in different regions of Iran [9], this study aims to determine the level of SAD and its related factors in preschool children in northern Iran.

Material and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2019 in Rasht, north of Iran. The study population includes all parents who enrolled their children in preschools affiliated to the welfare organization of Rasht. Inclusion criteria were: Having a child aged 3-6 years, literacy, being physically and mentally healthy, and enrolling a child in the selected preschool for more than a month. The exclusion criterion was the unwillingness to attend the study. Based on these criteria, 567 eligible parents of children aged 3-6 years participated in the study. The sample size was determined according to the mean SAD score (71.87±9.9) reported by Talaienejad et al. [15] at a 95% confidence interval. The sampling was done using a one-stage cluster sampling method. For sampling, a list of all government and non-government preschools under the supervision of the welfare organization of Rasht city was first prepared. After giving them a number, and determining the average number of children in each preschool, a number was randomly selected from the list and the samples were randomly recruited from that preschool. Before collecting data, after coordination with the principal of the selected preschools, the study objectives were explained to the parents.

To collect data, a demographic form and the separation anxiety assessment scale-parent version (SAAS-P) were used. The demographic form surveys child characteristics (gender, age, weight, birth rank, age of attendance in preschool, duration of enrollment in preschool, birth status [mature or premature], type of delivery, history of hospitalization, amount of sleep per night/day, place of sleep, and medical history), parental characteristics (mother’s age, mother’s education, mother’s occupation, history of postpartum depression, mother’s history of smoking during pregnancy and present, mother’s history of alcohol and drug use, corporal/verbal punishment of the child, father’s age, father’s education, monthly family income, father’s history of smoking, father’s history of alcohol and drug use, marital status of parents, and parents’ quarrel at home) and characteristics of the child’s living environment (number of siblings, place of residence, number of family members, type of family (nuclear or extended), history of the recent death of first-degree relatives, parents’ continuing education, use of computer games during the day, hours of playing computer games per day, the child’s interest in exciting news, the child’s interest in watching horror movies, and the child’s attendance in certain sports classes. The questionnaires were completed based on a self-report method. The SAAS-P has 34 items rated on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (always). It has four symptom dimensions: Fear of being alone, fear of abandonment, fear of physical illness, and worry about calamitous events. It also has two dimensions of “frequency of calamitous events” and the “safety signals index”. The overall score of this scale is in the range of 34-136. This tool was designed by Hahn et al. [14], and the psychometric properties of its Persian version were assessed by Talaienejad et al. [15]. In this study, the reliability using Cronbach’s α was estimated to be 0.71 for the overall scale.

In the present study, continuous variables were expressed as Mean±SD and categorical variables as frequency (percentage). The Spearman correlation test, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Friedman’s test were used to analyze data. The multiple linear regression analysis was used to determine the predictors of SAD. Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS software, version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

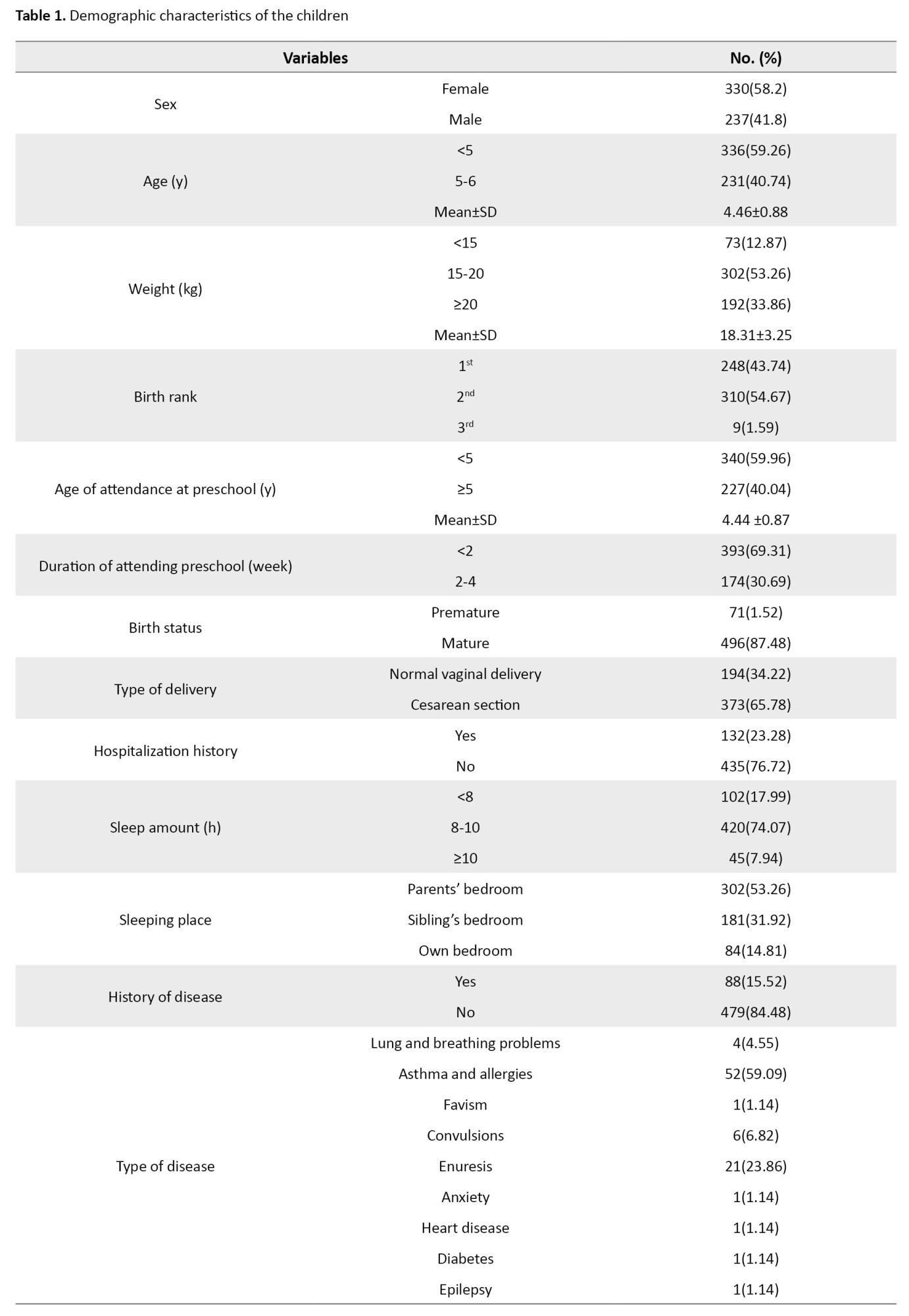

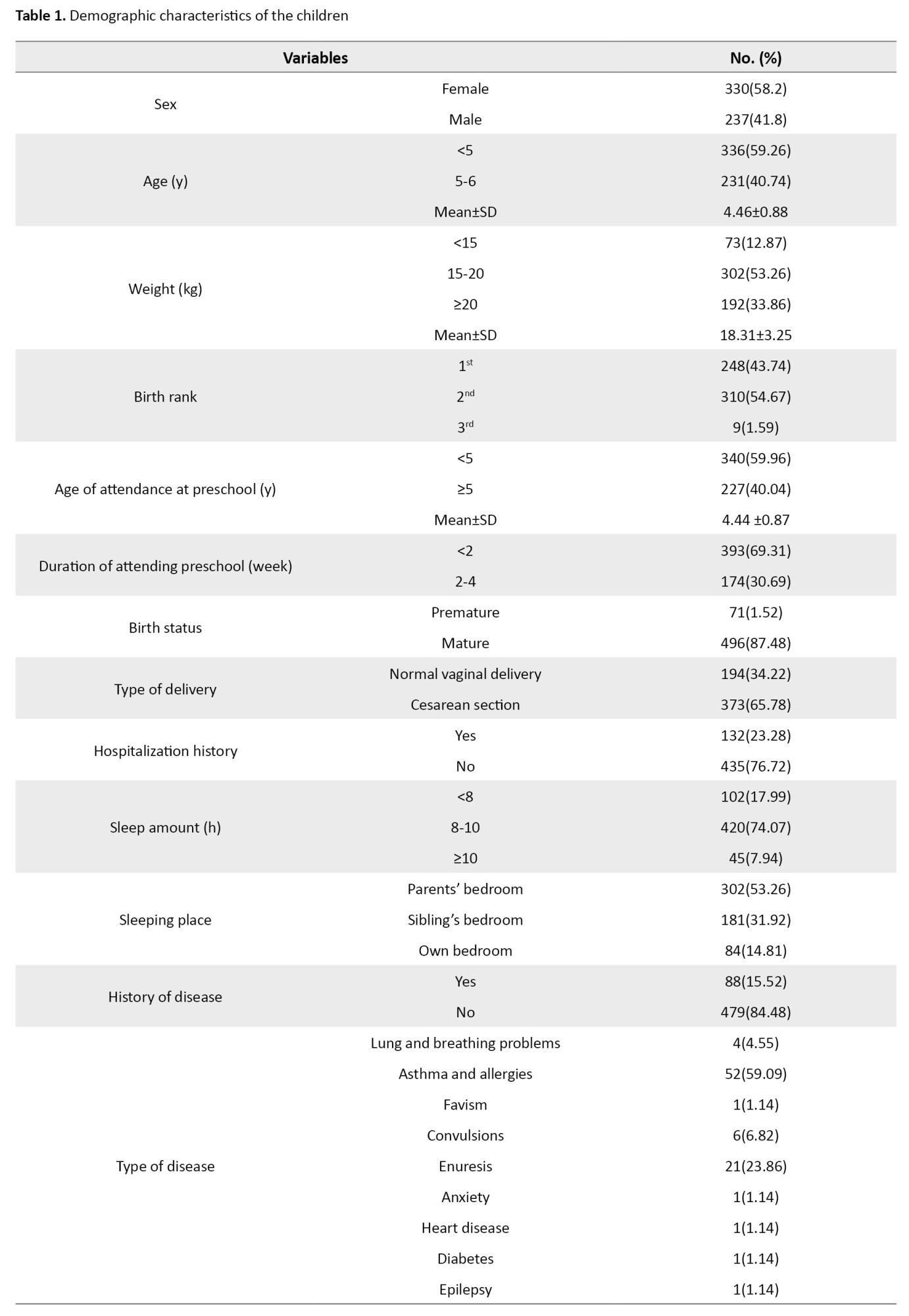

Most of the children were girls (58.2%) aged <5 years (59.36%). Other information about the characteristics of children is shown in Table 1.

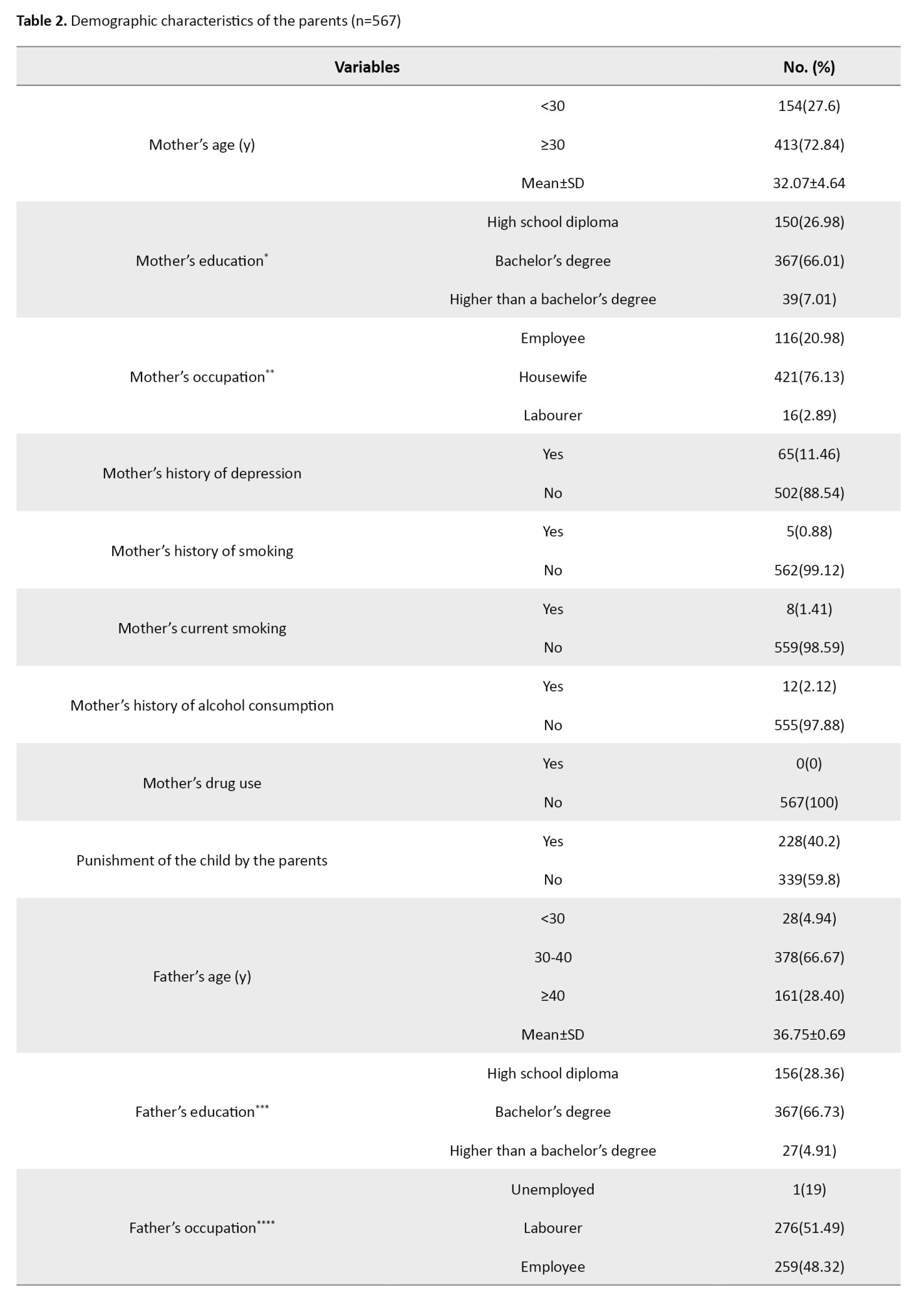

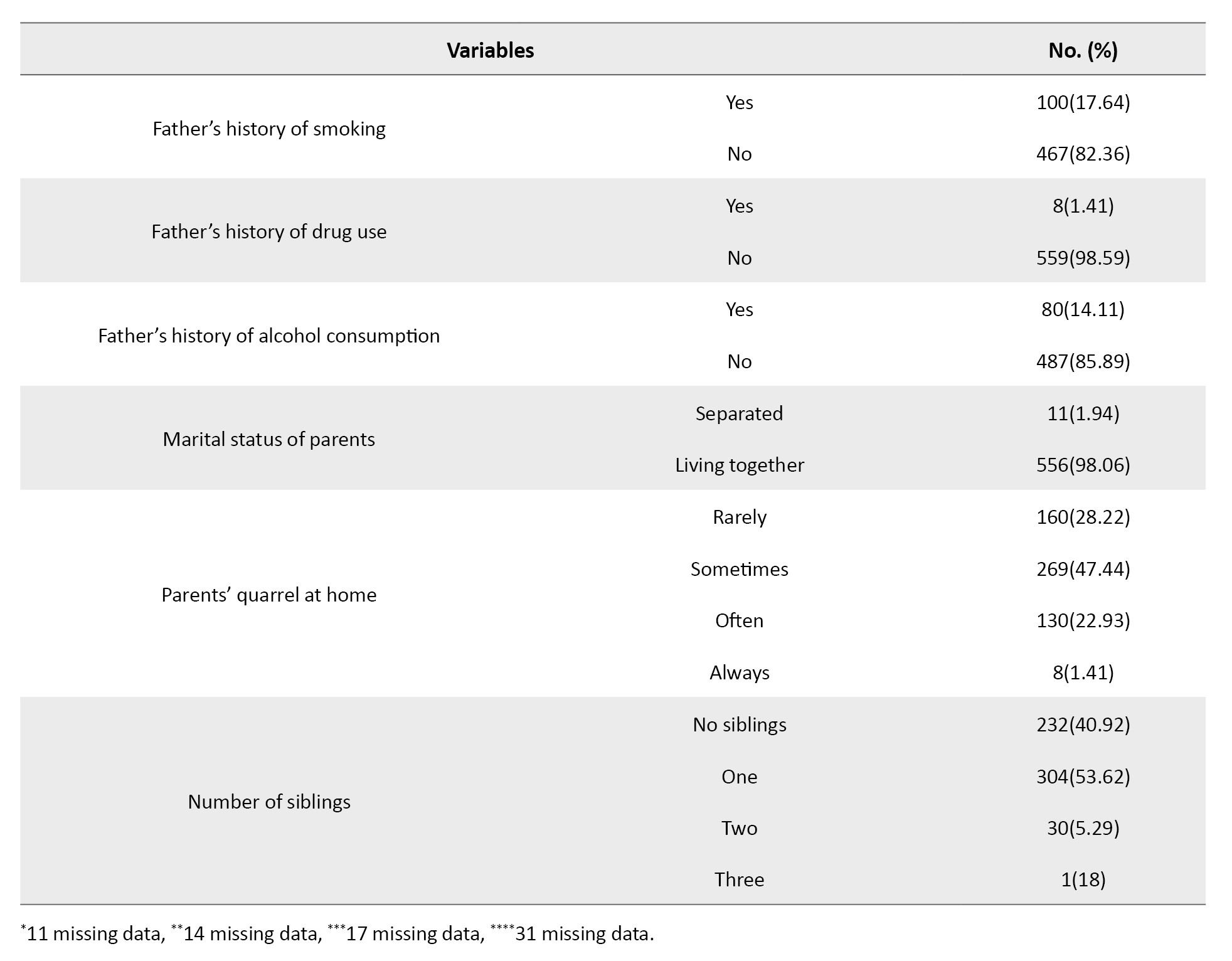

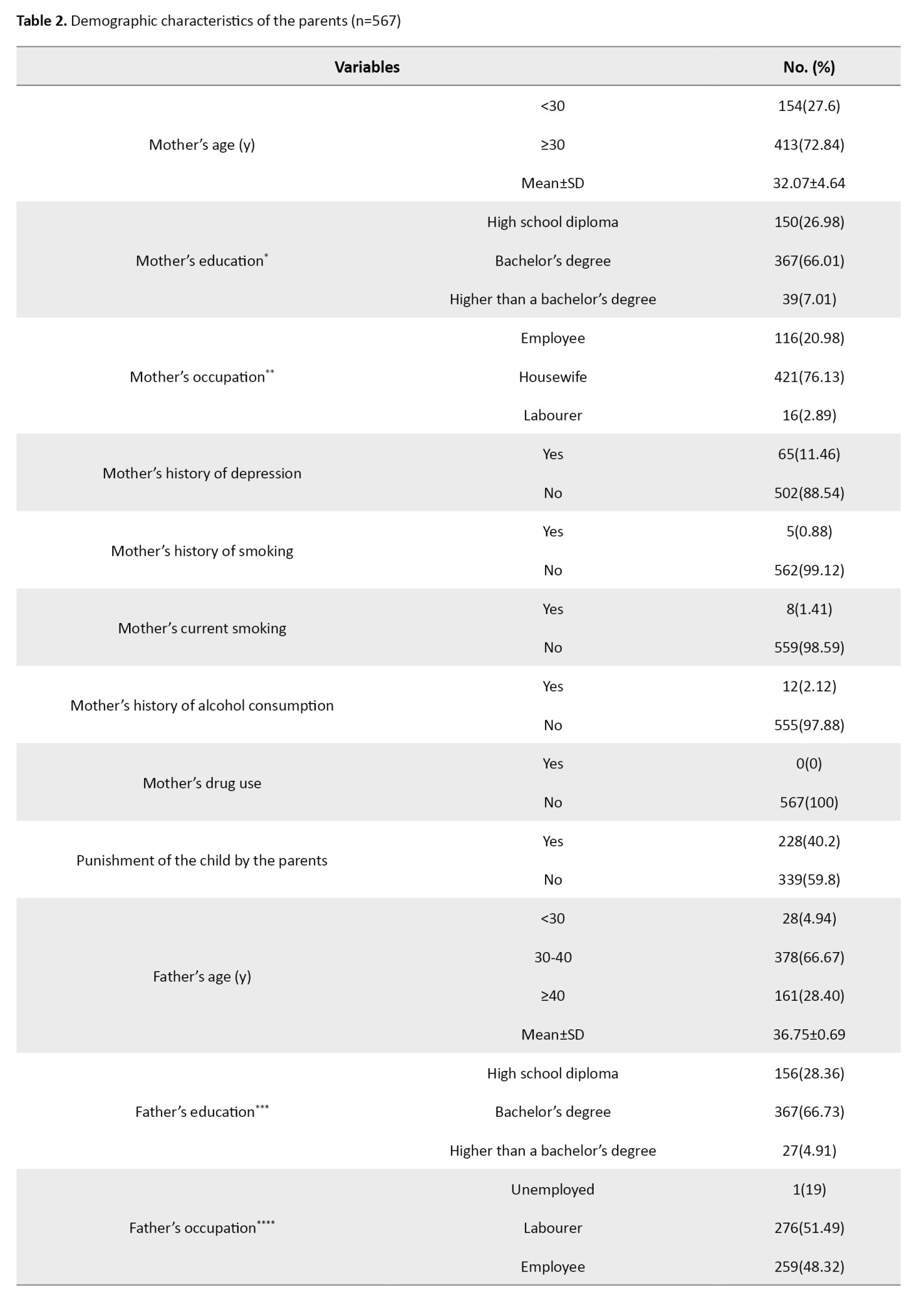

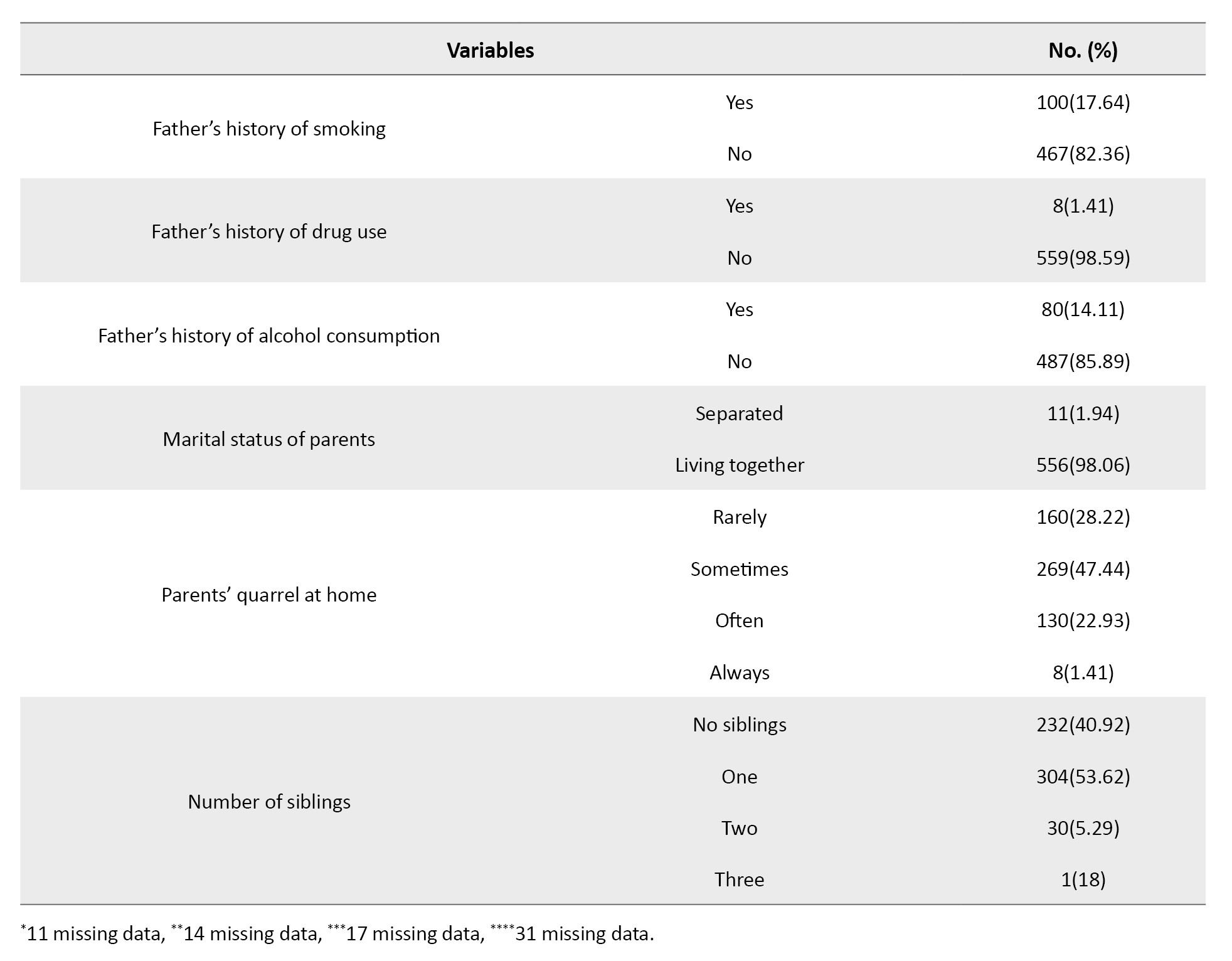

Most of the mothers were older than 30 years (72.84%) and housewives (76.13%) with a bachelor’s degree (66.01%). Most of the fathers were 30-40 years old (66.67%) and workers (51.49%) with no history of smoking (82.36%) and alcohol use (85.89%). Other information about the characteristics of parents is shown in Table 2.

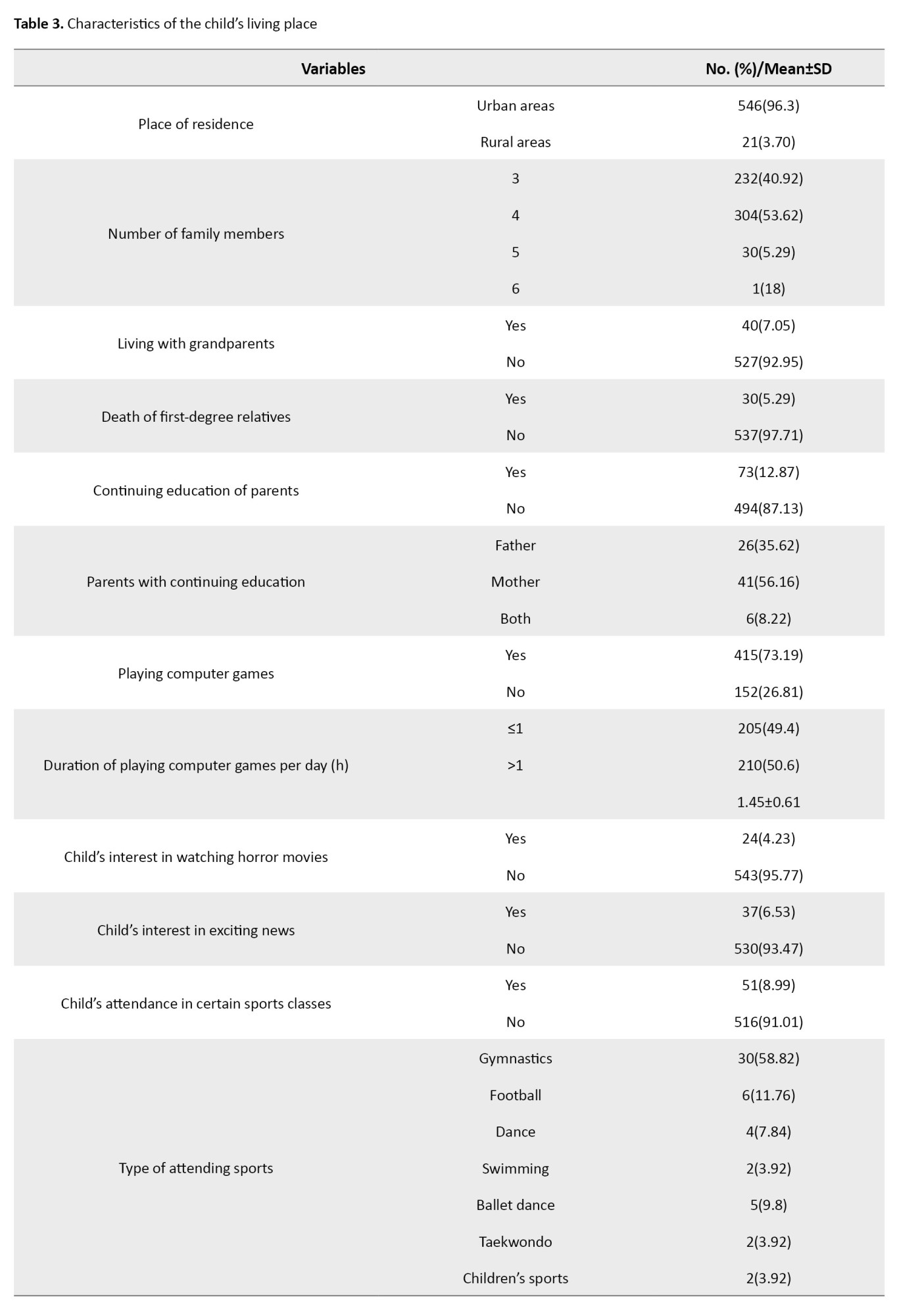

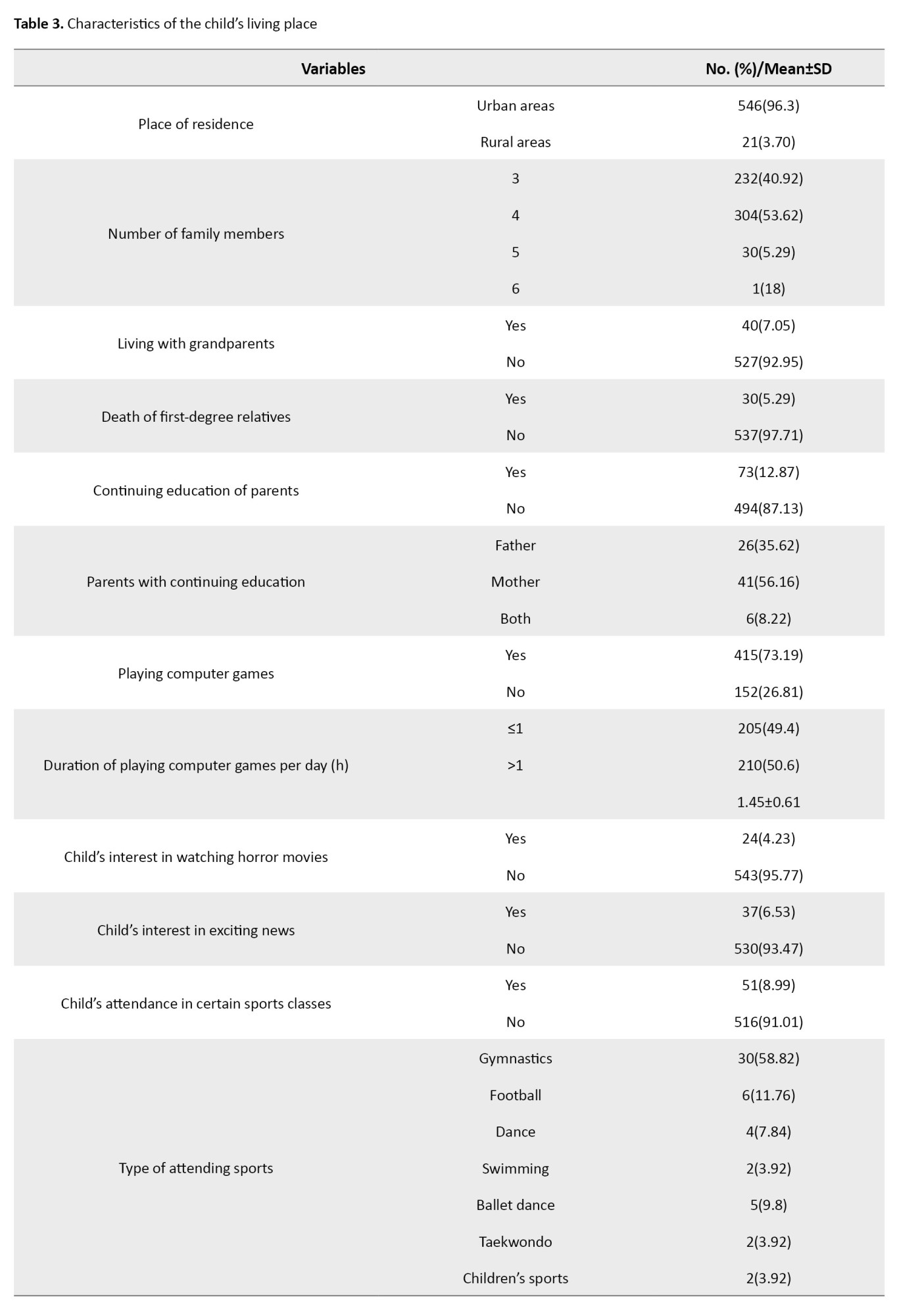

Regarding the living place, most of the participants were from urban areas (96.30%). Most of them had nuclear families (92.95%) with four members (53.62%). Most of the children did not report the experience of the death of a first-degree relative (97.71%). Other information about the characteristics of the living place is shown in Table 3.

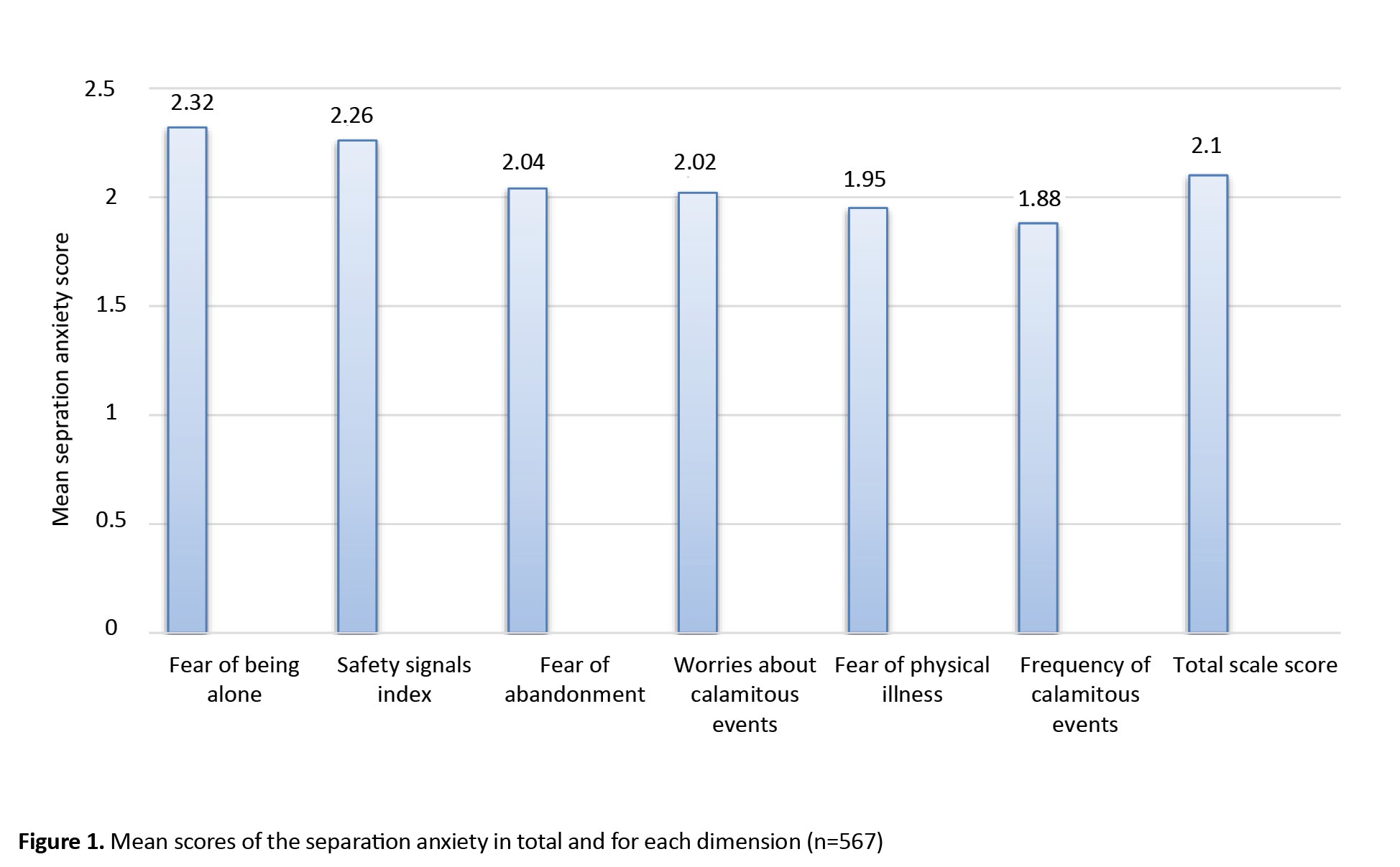

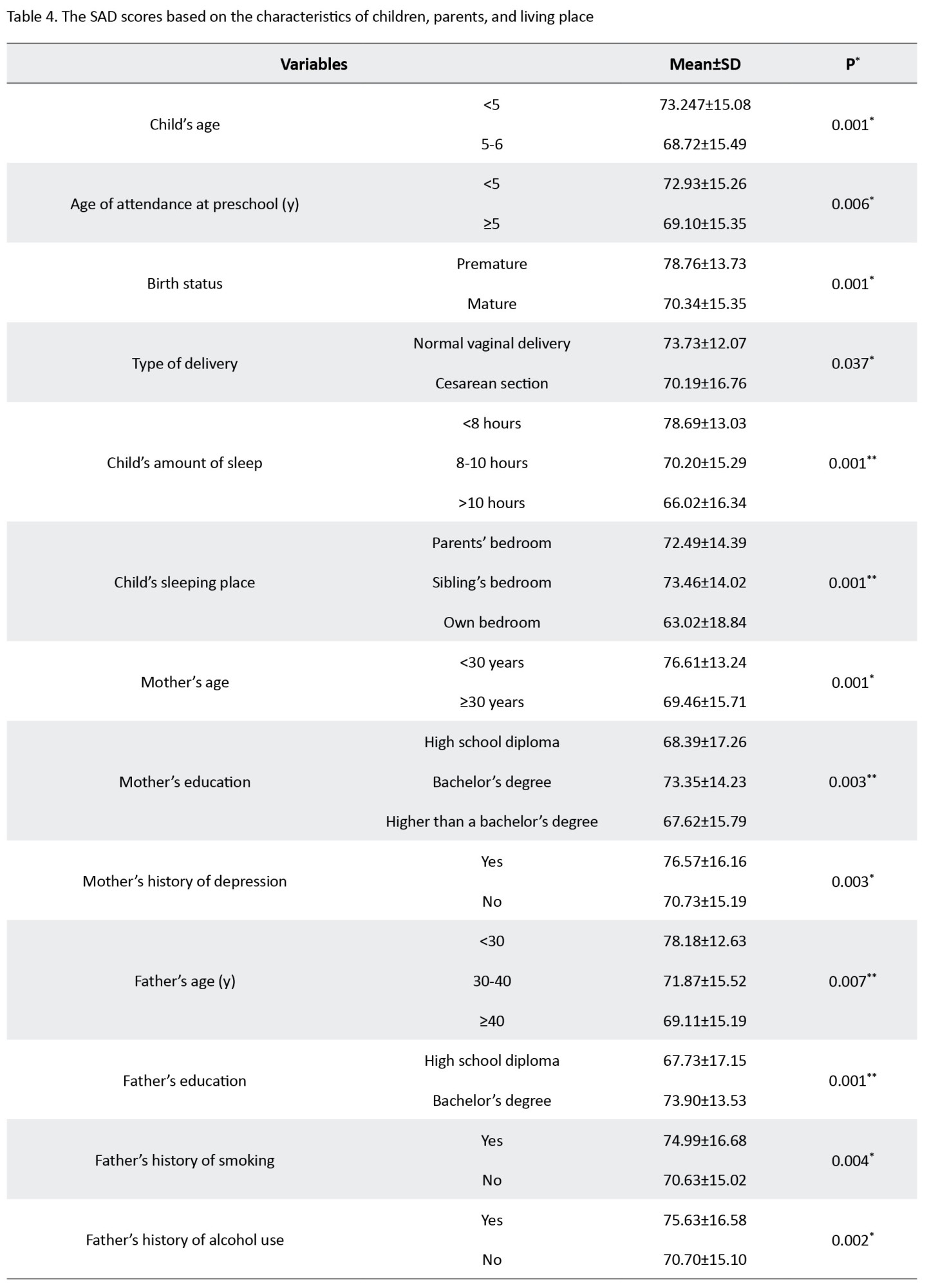

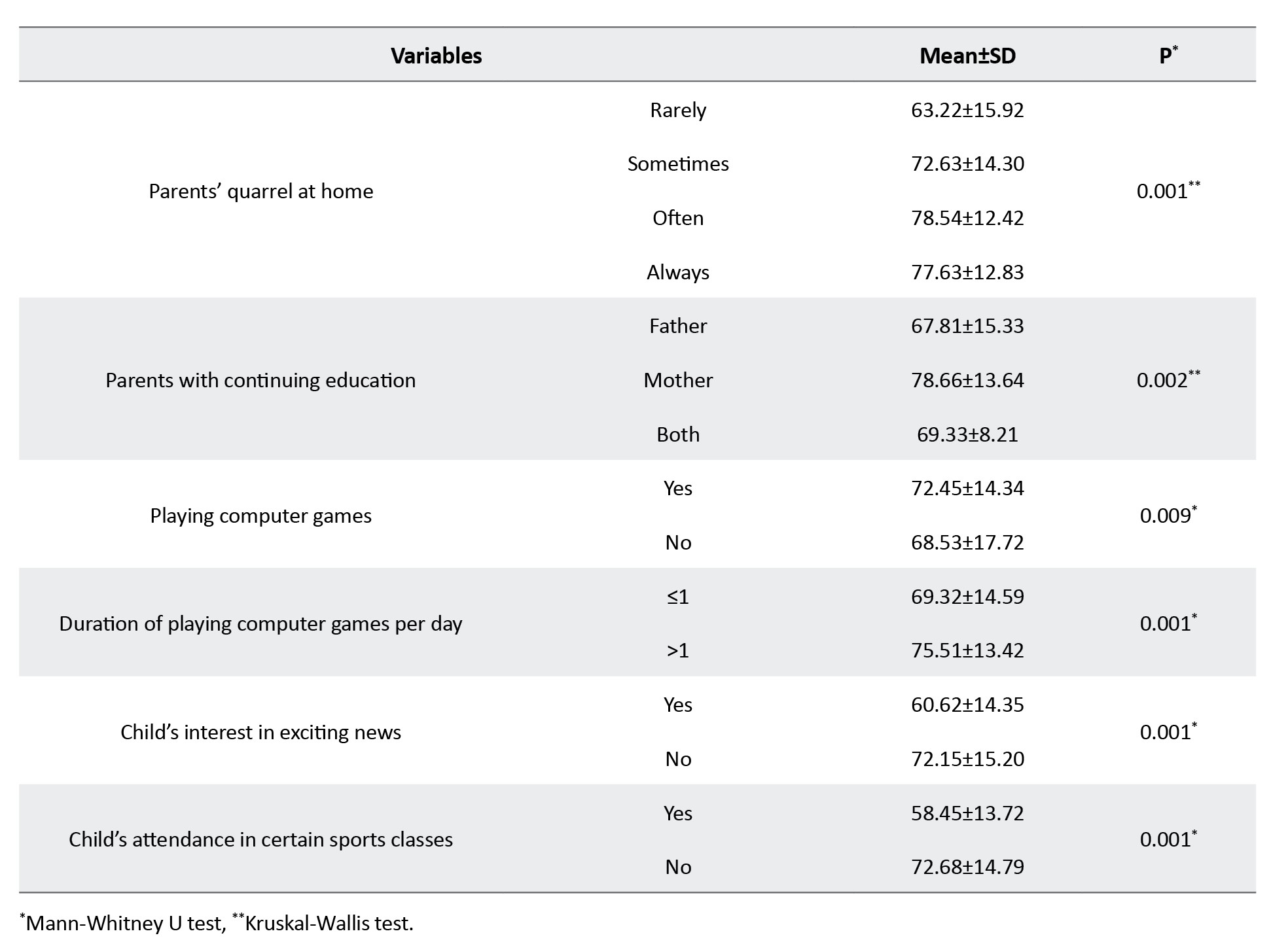

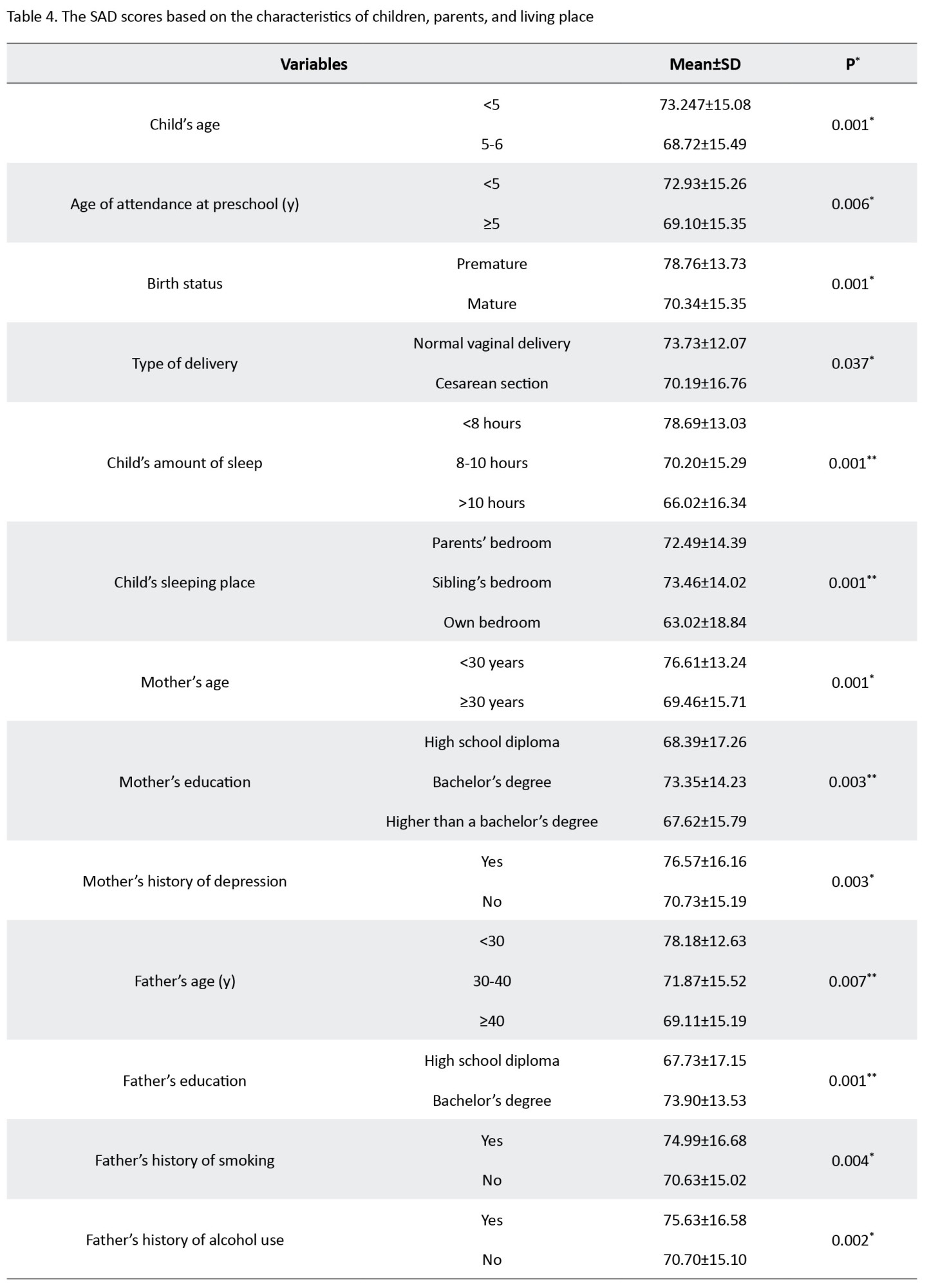

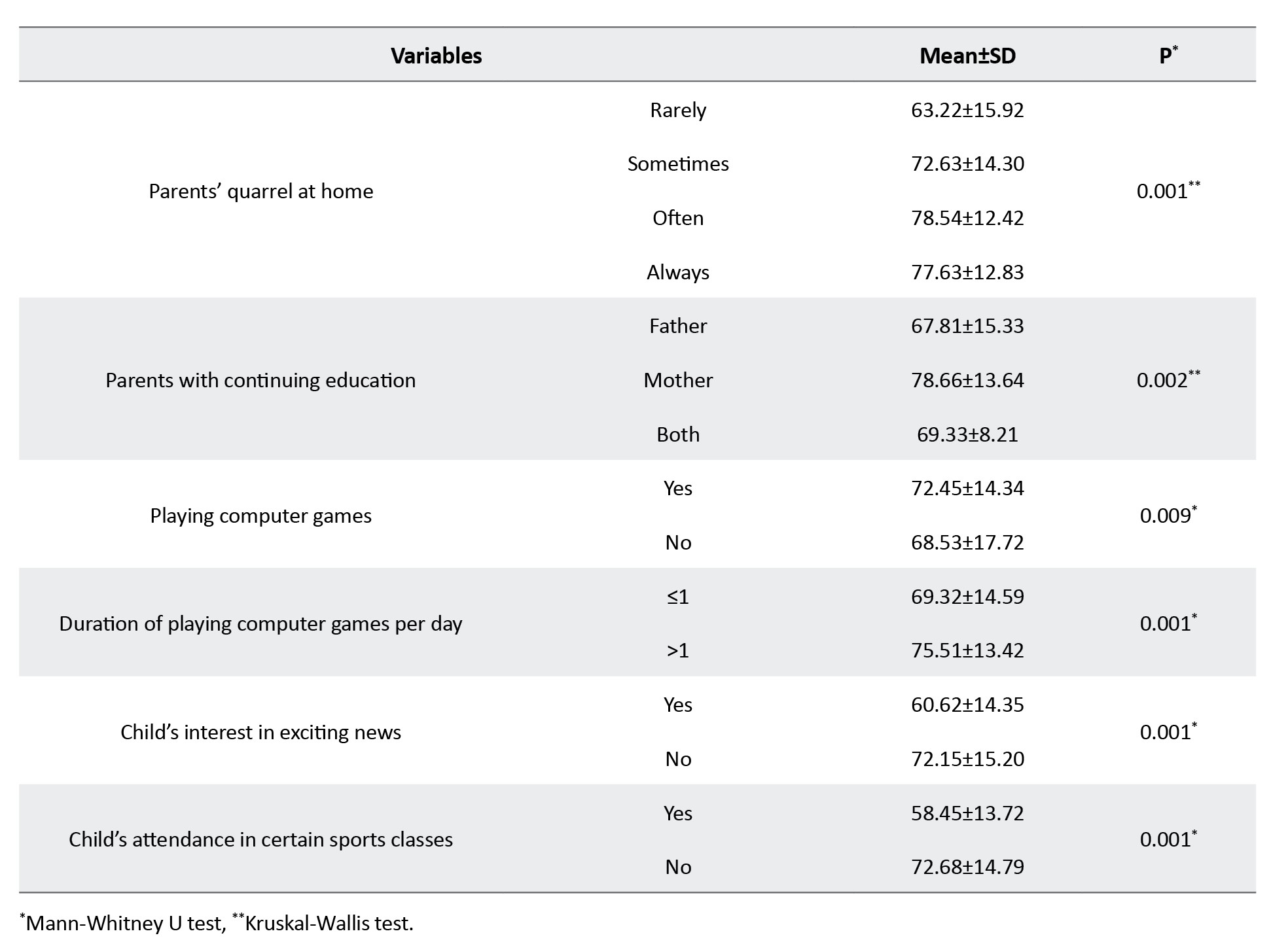

Figure 1 shows the scores of separation anxiety for each dimension. The results of Friedman’s test showed a statistically significant difference in the scores of separation anxiety based on the characteristics of children, parents, and living place (P=0.001). The results in Table 4 showed that the separation anxiety score was significantly different based on the child age (P=0.001), age at preschool attendance (P=0.006), birth status (P=0.001), type of delivery (P=0.037), amount of sleep (P=0.001), place of sleep (P=0.001), mother’s age (P=0.001), mother’s education (P=0.001), mother’s history of depression (P=0.003), father’s age (P=0.007), father’s education (P=0.001), father’s history of smoking (P=0.004), father’s history of alcohol consumption (P=0.002), parents’ quarrel at home (P=0.001), continuing education of parents (P=0.002), playing computer games (P=0.009), duration of playing computer games per day (P=0.001), the child’s interest in exciting news (P=0.001) and the child’s attendance in certain sports classes (P=0.001).

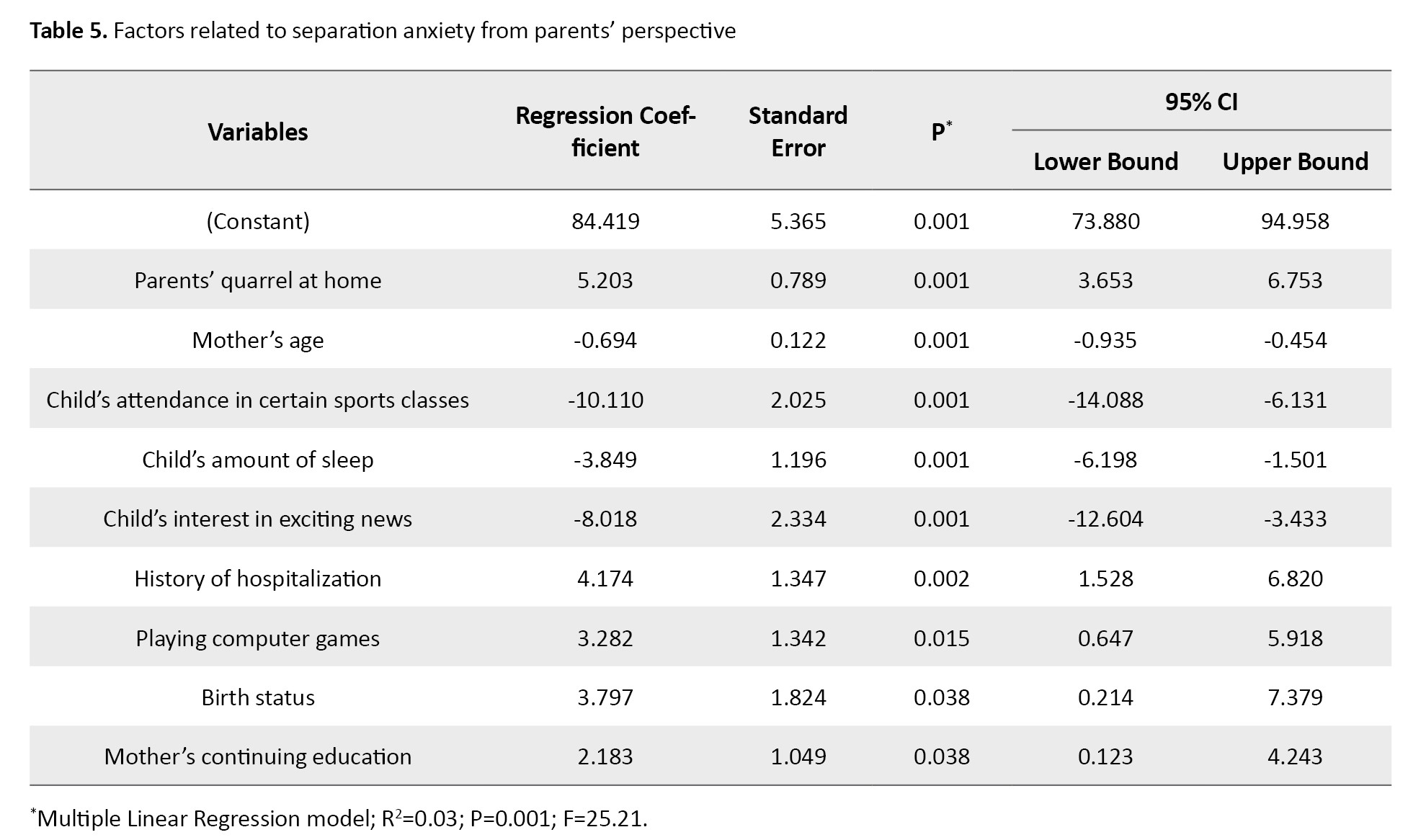

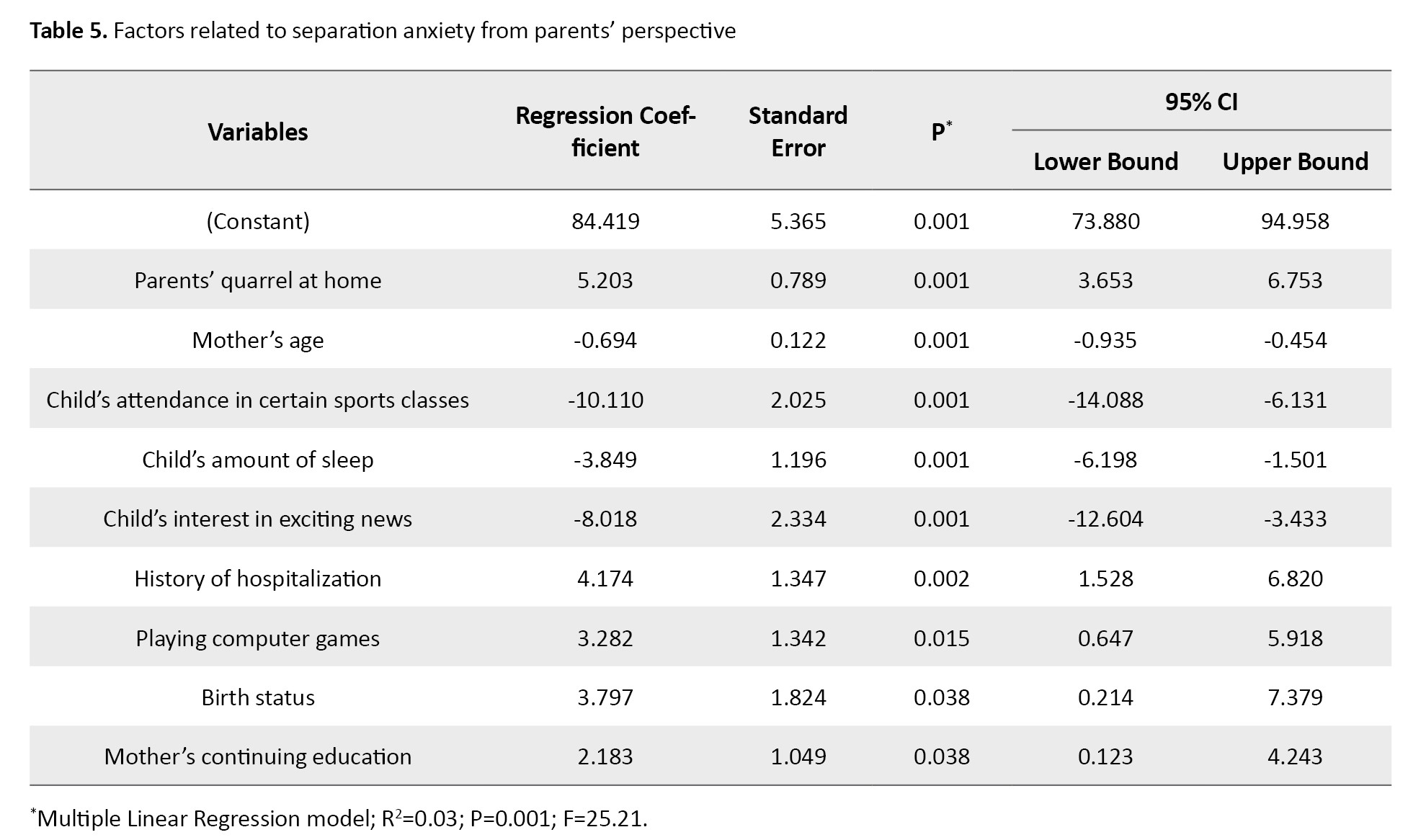

In the study of the factors related to the separation anxiety in children, the findings of multiple linear regression analysis (Table 5) showed that the following factors were the predictors of increasing separation anxiety in children: Parents’ quarrel at home (β=5.203, 95% CI; 3.653%, 6.753%, P=0.001), history of hospitalization (β=4.174, 95% CI; 1.528%, 6.820%, P=0.002), playing computer games (β=3.282, 95% CI; 0.647%, 5.918%, P=0.015), premature birth (β=3.797, 95% CI; 0.214%, 7.379%, P=0.038) and mother’s continuing education (β=2.183, 95% CI; 0.123%, 4.243%, P=0.038).

On the other hand, the predictors of decreasing separation anxiety in children were: Mother’s age (β=-0.694, 95% CI; -0.935 %, -0.454%, P=0.001), child’s attendance in certain sports classes (β=-10.110, 95% CI; -14.088%, -6.131%, P=0.001), hours of sleep (β=-3.849, 95% CI; -6.198%, -1.501%, P=0.001), and child’s interest in exciting news (β=-8.018, 95% CI; -12.604%, -3.433%, P=0.001).

Discussion

The findings indicated that the separation anxiety score of children in the dimension of fear of being left alone was higher than in other dimensions, which is consistent with Cooper-Vince et al.’s study [16]. Conversely, a study reported that the highest separation anxiety score was related to the fear of physical illness [17]. The reason for this discrepancy can be the difference in the age group of the children. In our study, the children who were born prematurely and those born by cesarean section had higher separation anxiety scores. Moreover, the children who slept in own rooms for more than ten hours per night had lower separation anxiety. Consistent with these findings, a study reported that most children typically experience separation anxiety at the age of 1.5-6 years, and its rate is expected to decrease with aging. Other studies have also shown the effect of prenatal factors and risk factors during pregnancy on the incidence of separation anxiety in children [3]. Sleeping with parents has been reported as a risk factor for separation anxiety in children [18], which is consistent with the present study.

The separation anxiety score in children with older parents, having a mother with no history of depression, having a father with no history of smoking and alcohol consumption, having parents with a diploma, and having parents with no quarrels at home was lower compared to other children. In this regard, a study reported that the highest prevalence of anxiety disorders in Iranian children was in those whose mothers had a bachelor’s degree [12], while a study showed no statistically significant relationship between mothers’ education and child anxiety [8]. The reason for this discrepancy seems to be cultural differences. The existence of appropriate support systems for children, especially in the pre-school age, significantly reduces the risk of significant clinical problems in children [19].

Moreover, the separation anxiety score in children whose mothers had continuing education and in those playing computer games for more than one hour per day was higher than in other children. On the other hand, separation anxiety in children interested in exciting news and those attended special sports classes was lower. It seems that mother’s education and the role conflict in her life cause or exacerbate maternal anxiety, which has been reported in other studies [3, 20]. Sports and physical activity can be effective factors in protecting children from anxiety [21, 22]. The use of computer games significantly increased the separation anxiety of children, which is consistent with the findings of other studies [23, 24].

Studies have shown that when there are conflicts between parents, their children are very anxious about the future and are worried about being left alone by one of them [3]. Another factor influencing the increase in separation anxiety in children was the history of hospitalization, This is an unpleasant and anxious experience not only for the child but also for the family [25]. In children, due to cognitive and emotional limitations as well as dependence on parents, the ability to adapt to an environment is low, which makes the children more vulnerable and anxious [26, 27].

According to the findings of this study, premature birth was associated with an increase in separation anxiety in children. The level of anxiety in mothers with premature infants is higher than in mothers with mature infants [28]. Based on the findings of this study, as the mother becomes older, the separation anxiety of her child decreases. With the increase in parents’s age, their parenting skills improve, which in turn reduces the perceived stress in parents and, as a result, reduces the behaviors that can cause anxiety in children. This is consistent with Gharibi et al.’s findings [29]. Another factor in reducing children’s separation anxiety was their interest in exciting news. It seems that, with increasing interest in exciting news and stories and the ability to imagine the story and its heroes, the children’s ability to express their feelings increases which can reduce their anxiety.

One of the limitations of the present study was the selection of 3-6 year old children and not considering children with younger ages. Therefore, caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings to all age groups of children. It is recommended that a more extensive study be conducted on children below this age range. Another limitation was the existence of missing data for some characteristics of parents.

The separation anxiety of children can be influenced by some socio-demographic characteristics of children, parents, and living environment. By considering these influential factors and providing counseling and emotional support to parents and children, and teaching effective interventions to parents to apply them on their children, an effective step can be taken to promote family-centered care and children’s health.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Guilan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1398.236). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the study objectives to them.

Funding

This study was funded by Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Yasaman Yaghobi, Fatemeh Falahzade, and Mahshid Mirzaei; Data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation: Fatemeh Falahzade and Yasaman Yaghobi; Statistical analysis: Ehsan Kazemnezhad Leili and Fatemeh Falahzade; Drafting of the manuscript: Mahshid Mirzaei and Fatemeh Falahzade; Supervision, project administration, review and editing: Yasaman Yaghobi, Mahshid Mirzaei, and Fatemeh Hosseinzadeh Siboni; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, The Welfare Organization of Guilan, Iran, and all participants for their support and cooperation in this research.

References

Separation anxiety disorder (SAD) is one of the most common anxiety disorders in childhood. It refers to the exaggeration of developmentally normal anxiety when the child is unexpectedly separated from home or an attachment figure and enters a new neighborhood or school, death, or illness of close relatives [1, 2]. It is a normal phase of development in children aged 1-3 years [3]. Children normally experience some degree of fear, anxiety, or worry about seeing strangers, being alone, and facing new situations, from about six months to a few years before school [4]. Most of the identified cases of SAD have been in one-and-a-half-year-old children. Gradual improvement is expected at the age of 4-5 years [3, 5]. In Iran, the prevalence of SAD in children is 5.3% [6]. The presence of progressive SAD at older ages in children may indicate a risk of developing anxiety disorders. Persistence of SAD disrupts the child’s daily life and can lead to anxiety disorders [3]. It is also a predictor of psychiatric disorders in adolescence; if it is left untreated, it can cause the disorder to continue into adulthood [7]. Anxiety disorders are very important because of their high prevalence [8] and negative functional consequences [4]. According to studies, the prevalence of SAD in Iranian children and adolescents ranges from 0.7-15.7% [9].

Environmental factors [4], family/culture, maternal depression, maternal smoking during pregnancy, parental unemployment [5, 8], parental divorce [10], parenting styles, parental self-efficacy [11], parents’ educational level, parents’ age, place of residence, mother’s job [12], socioeconomic conditions, genetics [4], having a single parent, number of siblings [13], prenatal risk factors [3], severe family environmental stressors [14], socio-emotional behaviors of children, child age, and child gender [8]. have been mentioned as factors affecting childhood SAD. To manage this problem, structured, comprehensive training programs and interventions are needed [5]. In this regard, and due to the statistical heterogeneity in different regions of Iran [9], this study aims to determine the level of SAD and its related factors in preschool children in northern Iran.

Material and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2019 in Rasht, north of Iran. The study population includes all parents who enrolled their children in preschools affiliated to the welfare organization of Rasht. Inclusion criteria were: Having a child aged 3-6 years, literacy, being physically and mentally healthy, and enrolling a child in the selected preschool for more than a month. The exclusion criterion was the unwillingness to attend the study. Based on these criteria, 567 eligible parents of children aged 3-6 years participated in the study. The sample size was determined according to the mean SAD score (71.87±9.9) reported by Talaienejad et al. [15] at a 95% confidence interval. The sampling was done using a one-stage cluster sampling method. For sampling, a list of all government and non-government preschools under the supervision of the welfare organization of Rasht city was first prepared. After giving them a number, and determining the average number of children in each preschool, a number was randomly selected from the list and the samples were randomly recruited from that preschool. Before collecting data, after coordination with the principal of the selected preschools, the study objectives were explained to the parents.

To collect data, a demographic form and the separation anxiety assessment scale-parent version (SAAS-P) were used. The demographic form surveys child characteristics (gender, age, weight, birth rank, age of attendance in preschool, duration of enrollment in preschool, birth status [mature or premature], type of delivery, history of hospitalization, amount of sleep per night/day, place of sleep, and medical history), parental characteristics (mother’s age, mother’s education, mother’s occupation, history of postpartum depression, mother’s history of smoking during pregnancy and present, mother’s history of alcohol and drug use, corporal/verbal punishment of the child, father’s age, father’s education, monthly family income, father’s history of smoking, father’s history of alcohol and drug use, marital status of parents, and parents’ quarrel at home) and characteristics of the child’s living environment (number of siblings, place of residence, number of family members, type of family (nuclear or extended), history of the recent death of first-degree relatives, parents’ continuing education, use of computer games during the day, hours of playing computer games per day, the child’s interest in exciting news, the child’s interest in watching horror movies, and the child’s attendance in certain sports classes. The questionnaires were completed based on a self-report method. The SAAS-P has 34 items rated on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (always). It has four symptom dimensions: Fear of being alone, fear of abandonment, fear of physical illness, and worry about calamitous events. It also has two dimensions of “frequency of calamitous events” and the “safety signals index”. The overall score of this scale is in the range of 34-136. This tool was designed by Hahn et al. [14], and the psychometric properties of its Persian version were assessed by Talaienejad et al. [15]. In this study, the reliability using Cronbach’s α was estimated to be 0.71 for the overall scale.

In the present study, continuous variables were expressed as Mean±SD and categorical variables as frequency (percentage). The Spearman correlation test, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Friedman’s test were used to analyze data. The multiple linear regression analysis was used to determine the predictors of SAD. Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS software, version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Most of the children were girls (58.2%) aged <5 years (59.36%). Other information about the characteristics of children is shown in Table 1.

Most of the mothers were older than 30 years (72.84%) and housewives (76.13%) with a bachelor’s degree (66.01%). Most of the fathers were 30-40 years old (66.67%) and workers (51.49%) with no history of smoking (82.36%) and alcohol use (85.89%). Other information about the characteristics of parents is shown in Table 2.

Regarding the living place, most of the participants were from urban areas (96.30%). Most of them had nuclear families (92.95%) with four members (53.62%). Most of the children did not report the experience of the death of a first-degree relative (97.71%). Other information about the characteristics of the living place is shown in Table 3.

Figure 1 shows the scores of separation anxiety for each dimension. The results of Friedman’s test showed a statistically significant difference in the scores of separation anxiety based on the characteristics of children, parents, and living place (P=0.001). The results in Table 4 showed that the separation anxiety score was significantly different based on the child age (P=0.001), age at preschool attendance (P=0.006), birth status (P=0.001), type of delivery (P=0.037), amount of sleep (P=0.001), place of sleep (P=0.001), mother’s age (P=0.001), mother’s education (P=0.001), mother’s history of depression (P=0.003), father’s age (P=0.007), father’s education (P=0.001), father’s history of smoking (P=0.004), father’s history of alcohol consumption (P=0.002), parents’ quarrel at home (P=0.001), continuing education of parents (P=0.002), playing computer games (P=0.009), duration of playing computer games per day (P=0.001), the child’s interest in exciting news (P=0.001) and the child’s attendance in certain sports classes (P=0.001).

In the study of the factors related to the separation anxiety in children, the findings of multiple linear regression analysis (Table 5) showed that the following factors were the predictors of increasing separation anxiety in children: Parents’ quarrel at home (β=5.203, 95% CI; 3.653%, 6.753%, P=0.001), history of hospitalization (β=4.174, 95% CI; 1.528%, 6.820%, P=0.002), playing computer games (β=3.282, 95% CI; 0.647%, 5.918%, P=0.015), premature birth (β=3.797, 95% CI; 0.214%, 7.379%, P=0.038) and mother’s continuing education (β=2.183, 95% CI; 0.123%, 4.243%, P=0.038).

On the other hand, the predictors of decreasing separation anxiety in children were: Mother’s age (β=-0.694, 95% CI; -0.935 %, -0.454%, P=0.001), child’s attendance in certain sports classes (β=-10.110, 95% CI; -14.088%, -6.131%, P=0.001), hours of sleep (β=-3.849, 95% CI; -6.198%, -1.501%, P=0.001), and child’s interest in exciting news (β=-8.018, 95% CI; -12.604%, -3.433%, P=0.001).

Discussion

The findings indicated that the separation anxiety score of children in the dimension of fear of being left alone was higher than in other dimensions, which is consistent with Cooper-Vince et al.’s study [16]. Conversely, a study reported that the highest separation anxiety score was related to the fear of physical illness [17]. The reason for this discrepancy can be the difference in the age group of the children. In our study, the children who were born prematurely and those born by cesarean section had higher separation anxiety scores. Moreover, the children who slept in own rooms for more than ten hours per night had lower separation anxiety. Consistent with these findings, a study reported that most children typically experience separation anxiety at the age of 1.5-6 years, and its rate is expected to decrease with aging. Other studies have also shown the effect of prenatal factors and risk factors during pregnancy on the incidence of separation anxiety in children [3]. Sleeping with parents has been reported as a risk factor for separation anxiety in children [18], which is consistent with the present study.

The separation anxiety score in children with older parents, having a mother with no history of depression, having a father with no history of smoking and alcohol consumption, having parents with a diploma, and having parents with no quarrels at home was lower compared to other children. In this regard, a study reported that the highest prevalence of anxiety disorders in Iranian children was in those whose mothers had a bachelor’s degree [12], while a study showed no statistically significant relationship between mothers’ education and child anxiety [8]. The reason for this discrepancy seems to be cultural differences. The existence of appropriate support systems for children, especially in the pre-school age, significantly reduces the risk of significant clinical problems in children [19].

Moreover, the separation anxiety score in children whose mothers had continuing education and in those playing computer games for more than one hour per day was higher than in other children. On the other hand, separation anxiety in children interested in exciting news and those attended special sports classes was lower. It seems that mother’s education and the role conflict in her life cause or exacerbate maternal anxiety, which has been reported in other studies [3, 20]. Sports and physical activity can be effective factors in protecting children from anxiety [21, 22]. The use of computer games significantly increased the separation anxiety of children, which is consistent with the findings of other studies [23, 24].

Studies have shown that when there are conflicts between parents, their children are very anxious about the future and are worried about being left alone by one of them [3]. Another factor influencing the increase in separation anxiety in children was the history of hospitalization, This is an unpleasant and anxious experience not only for the child but also for the family [25]. In children, due to cognitive and emotional limitations as well as dependence on parents, the ability to adapt to an environment is low, which makes the children more vulnerable and anxious [26, 27].

According to the findings of this study, premature birth was associated with an increase in separation anxiety in children. The level of anxiety in mothers with premature infants is higher than in mothers with mature infants [28]. Based on the findings of this study, as the mother becomes older, the separation anxiety of her child decreases. With the increase in parents’s age, their parenting skills improve, which in turn reduces the perceived stress in parents and, as a result, reduces the behaviors that can cause anxiety in children. This is consistent with Gharibi et al.’s findings [29]. Another factor in reducing children’s separation anxiety was their interest in exciting news. It seems that, with increasing interest in exciting news and stories and the ability to imagine the story and its heroes, the children’s ability to express their feelings increases which can reduce their anxiety.

One of the limitations of the present study was the selection of 3-6 year old children and not considering children with younger ages. Therefore, caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings to all age groups of children. It is recommended that a more extensive study be conducted on children below this age range. Another limitation was the existence of missing data for some characteristics of parents.

The separation anxiety of children can be influenced by some socio-demographic characteristics of children, parents, and living environment. By considering these influential factors and providing counseling and emotional support to parents and children, and teaching effective interventions to parents to apply them on their children, an effective step can be taken to promote family-centered care and children’s health.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Guilan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1398.236). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the study objectives to them.

Funding

This study was funded by Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Yasaman Yaghobi, Fatemeh Falahzade, and Mahshid Mirzaei; Data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation: Fatemeh Falahzade and Yasaman Yaghobi; Statistical analysis: Ehsan Kazemnezhad Leili and Fatemeh Falahzade; Drafting of the manuscript: Mahshid Mirzaei and Fatemeh Falahzade; Supervision, project administration, review and editing: Yasaman Yaghobi, Mahshid Mirzaei, and Fatemeh Hosseinzadeh Siboni; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, The Welfare Organization of Guilan, Iran, and all participants for their support and cooperation in this research.

References

- Walter HJ, Bukstein OG, Abright AR, Keable H, Ramtekkar U, Ripperger-Suhler J, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020; 59(10):1107-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.005]

- Feriante J, Torrico TJ, Bernstein B. Separation anxiety disorder. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [Link]

- Battaglia M, Touchette É, Garon-Carrier G, Dionne G, Côté SM, Vitaro F, et al. Distinct trajectories of separation anxiety in the preschool years: Persistence at school entry and early-life associated factors. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016; 57(1):39-46. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12424]

- Pirzadi H. The separation anxiety disorder: Characteristics, etiology and treatment methods. J Except Educ. 2018; 4(153):33-9. [Link]

- Pepito GM, Montalbo IC. Separation anxiety on preschoolers’ development. Int J Engl Educ. 2019; 8(1):229-39. [Link]

- Mohammadi MR, Pourdehghan P, Mostafavi SA, Hooshyari Z, Ahmadi N, Khaleghi A. Generalized anxiety disorder: Prevalence, predictors, and comorbidity in children and adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2020; 73:102234. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102234]

- Abbasi Z, Amiri S, Talebi H. [The effectiveness of modular cognitive-behavioral therapy (MCBT) on reducing the symptoms of separation anxiety in 6 and 7 year old children (Persian)]. Clin Psychol Personal. 2020; 13(2):51-64. [DOI:10.22070/13.2.51]

- Alipour G, Sayadi A, Haqiqi A. [Demographic characteristics and anxiety among children 5 to 6 years old (Persian)]. Zanko J Med Sci 2016; 17(52):55-64. [Link]

- Zarafshan H, Mohammadi MR, Salmanian M. Prevalence of anxiety disorders among children and adolescents in Iran: A systematic review. Iran J Psychiatry. 2015; 10(1):1-7. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ariapooran S, Abbasi M. [The symptoms of anxiety disorders, emotional expression and social acceptance in students with parental divorce and death experience and normal student (Persian)]. J Fam Res. 2020; 16(2):259-83. [Link]

- Okati N, Rezvani Shakib M, Asgari Nekah SM, Sadeghi Baygi M. [Investigating the role of self-efficacy and parenting style of mothers as predictors of anxiety in preschool children (Persian)]. J Torbat Heydariyeh Univ Med Sci. 2019; 6(4):57-64. [Link]

- Eslami Shahrbabaki M, Mohammadi MR, Hooshyari Z, Ahmadi A, Rabani Bavojdan M, Kaviani N, et al. [Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents in Kerman and suburbs in 2016-2017 (Persian)]. Health Dev J. 2020; 9(2):187-201. [Link]

- Franz L, Angold A, Copeland W, Costello EJ, Towe-Goodman N, Egger H. Preschool anxiety disorders in pediatric primary care: Prevalence and comorbidity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013; 52(12):1294-303. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.008).]

- Hahn L, Hajinlian J, Eisen A, Winder B, Pincus D. Measuring the dimensions of separation anxiety and early panic in children and adolescents: The separation anxiety assessment scale. Paper presented in: Recent Advances in the Treatment of Separation Anxiety and Panic in children and adolescents Presentado en la 37ª convención anual. 2003 November 1; Boston, Massachusetts. [Link]

- Talaienejad N, Ghanbari S, Mazaheri MA, Asgari A. [Separation Anxiety assessment scale (parent version): Instruction and scoring (Persian)]. Dev psychol. 2016; 12(47):225-35. [Link]

- Cooper-Vince CE, Emmert-Aronson BO, Pincus DB, Comer JS. The diagnostic utility of separation anxiety disorder symptoms: An item response theory analysis. J Abnormal Child Psychol. 2014; 42:417-28. [DOI:10.1007/s10802-013-9788-y]

- Faramarzi S, Bakrayi S, Mohebzadeh M, Aghaziarati A, Ranjbar B. The effectiveness of rhythmic movement games training on separation anxiety in children. Appl Fam Ther J. 2020; 1(3):66-83. [Link]

- Jansen PW, Saridjan NS, Hofman A, Jaddoe VW, Verhulst FC, Tiemeier H. Does disturbed sleeping precede symptoms of anxiety or depression in toddlers? The generation R study. Psychosom Med. 2011; 73(3):242-9. [DOI:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820a4abb]

- Parkes A, Green M, Mitchell K. Coparenting and parenting pathways from the couple relationship to children’s behavior problems. J Fam Psychol. 2019; 33(2):215. [DOI:10.1037/fam0000492]

- Stone LL, Otten R, Soenens B, Engels RC, Janssens JM. Relations between parental and child separation anxiety: The role of dependency-oriented psychological control. J Child Fam Stud. 2015; 24:3192-9. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-015-0122-x]

- Hedayati Varikani M, Borjali A, Bazargan S, Momenifar M. [The effectiveness of the physical education and music activities for reduction of anxiety in preschool children (Persian)]. J Curriculum Stud. 2019; 13(51):145-68. [Link]

- McDowell CP, Dishman RK, Gordon BR, Herring MP. Physical activity and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Prevent Med. 2019; 57(4):545-56. [DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.05.012]

- Agha NI, ZaaZa A. The effects of digital technology usage on children’s development and health. World Fam Med. 2021; 19:54-60. [Link]

- Poulain T, Vogel M, Neef M, Abicht F, Hilbert A, Genuneit J, et al. Reciprocal associations between electronic media use and behavioral difficulties in preschoolers. International J Environ Res Public Health. 2018; 15(4):814. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph15040814]

- Patel N, Vageriya V. Effect of psycho educational intervention on level of anxiety among hospitalized children: A systemic Literature review. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2019; 9(4-s):855-60. [DOI:10.22270/jddt.v9i4-s.3389]

- Lerwick JL. Minimizing pediatric healthcare-induced anxiety and trauma. World J Clin Pediatr. 2016; 5(2):143-50. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rokach A. Psychological, emotional and physical experiences of hospitalized children. Clin Case Rep Rev. 2016; 2(4):399-401. [DOI:10.15761/CCRR.1000227]

- Trumello C, Candelori C, Cofini M, Cimino S, Cerniglia L, Paciello M, et al. Mothers' depression, anxiety, and mental representations after preterm birth: A study during the infant's hospitalization in a neonatal intensive care unit. Front Public Health. 2018; 6:359. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00359]

- Gharibi H, Sheidai A, Rostami CH. [The effectiveness of parenting skills training on attachment, perceived stress and quality of life in mothers of preschool children (Persian)]. J Health Care. 2017; 18(4):292-305. [Link]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2024/03/9 | Accepted: 2024/05/26 | Published: 2024/10/1

Received: 2024/03/9 | Accepted: 2024/05/26 | Published: 2024/10/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |