Wed, Jan 28, 2026

Volume 36, Issue 1 (1-2026)

JHNM 2026, 36(1): 46-53 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Groohi-sardou S, Anaei Goudari A, Rahmanian V, Faryabi R, Ghasemian N, Goroei Sardou E et al . Patient-initiated discharge from emergency departments and the related factors in Jiroft, South of Iran. JHNM 2026; 36 (1) :46-53

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2280-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2280-en.html

Shima Groohi-sardou1

, Akbar Anaei Goudari2

, Akbar Anaei Goudari2

, Vahid Rahmanian3

, Vahid Rahmanian3

, Reza Faryabi4

, Reza Faryabi4

, Najmeh Ghasemian5

, Najmeh Ghasemian5

, Ehsan Goroei Sardou1

, Ehsan Goroei Sardou1

, Salman Daneshi *6

, Salman Daneshi *6

, Akbar Anaei Goudari2

, Akbar Anaei Goudari2

, Vahid Rahmanian3

, Vahid Rahmanian3

, Reza Faryabi4

, Reza Faryabi4

, Najmeh Ghasemian5

, Najmeh Ghasemian5

, Ehsan Goroei Sardou1

, Ehsan Goroei Sardou1

, Salman Daneshi *6

, Salman Daneshi *6

1- Assistant Professor, Clinical Research Development Unit, Imam Khomeini Hospital, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran.

2- Associate Professor, Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran.

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, Torbat Jam Faculty of Medical Sciences, Torbat Jam, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, School of Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran.

5- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, School of Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran. & Assistant professor, Department Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran.

6- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, School of Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran. ,salmandaneshi008@gmail.com

2- Associate Professor, Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran.

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, Torbat Jam Faculty of Medical Sciences, Torbat Jam, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, School of Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran.

5- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, School of Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran. & Assistant professor, Department Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran.

6- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, School of Health, Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 482 kb]

(39 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (72 Views)

References

Full-Text: (3 Views)

Introduction

Patients have the right to enter or leave the treatment centers with their consent and without the need for the treatment staff’s permission, but it is better for them to complete their treatment process and be discharged by the attending physician. Patient-initiated discharge can lead to adverse outcomes such as re-hospitalization, death, and increased hospital costs [1-3]. This topic is crucial in the emergency departments and Intensive Care Units (ICUs), as patients’ lives may be at risk. Patients who are discharged by personal consent often have acute illnesses with severe symptoms at the time of discharge [4, 5], and their prognosis is generally more unfavorable than that of patients discharged with the doctor’s approval [6]. Investigating the rate of patient-initiated discharge without completing the treatment process can be a measure of patient satisfaction with the treatment environment and system. To improve conditions and reduce the number of patients leaving the hospital with personal consent before completing their treatment, it is essential to identify the reasons for self-discharge and take steps to increase patient satisfaction [4, 6]. Patient-initiated discharge is the strongest predictor of readmission in the first 15 days after discharge; 21% of patients discharged by personal consent readmit within this period, and the rate of readmission in the first 7 days is 14% for these patients, compared to other patients (7%) [7].

According to statistics, there is a notable contradiction in the rate of patients with self-discharge between developed countries (such as the United States) and Iran. In the United States, it accounts for 0.8-2.2% of all discharge cases, particularly in teaching hospitals. However, in Iran, the rate is higher, ranging from 3% in mental hospitals to 20% in emergency departments [8]. Assessing the level of patient satisfaction in hospitals and identifying the underlying causes are fundamental steps toward enhancing the quality of medical services [9, 10]. Patient satisfaction with medical care is an essential indicator of the perceived quality of care. Low patient satisfaction can lead to poor cooperation with treatment staff, resulting in resource waste and diminished clinical outcomes. As a result, meeting patients’ needs and ensuring their satisfaction should be a primary goal across all forms of medical care. It should be regarded as an essential outcome measure [11]. Overall, self-discharge from a hospital can occur for various reasons, such as patient dissatisfaction with hospital services, delayed medical attention, high medical costs, personal and familial reasons, and inadequate hospital facilities and environment. The present study aimed to investigate the reasons for self-discharge from the emergency departments in Jiroft, Iran.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional and analytical study was conducted in 2022. Using a census method, all 341 patients discharged with personal consent from the emergency department of a teaching hospital affiliated with Jiroft University of Medical Sciences were included. The sample size was calculated based on a total population of approximately 3,000 individuals, using the single-population proportion formula. Due to the unknown proportion (p) in the study population, P=0.5 was assumed to yield the maximum required sample size. The confidence level was set at 95%, and the margin of error (d) was set at 0.05. Based on these parameters, the final sample size was estimated to be 341. The inclusion criterion was voluntary discharge from the emergency department of the study hospital. The exclusion criterion was unconsciousness or lack of cooperation to complete the checklist.

The data collection tool was a researcher-made checklist approved by five specialists. It had four sections. The first section surveyed the demographic characteristics of the patients. The second section surveyed the reasons for self-discharge related to patients, such as feeling sufficiently recovered, intention to continue treatment at home, family issues, dependence on children and spouse, not being a local resident, fear of ongoing therapy, loss of hope in recovery from disease, intention to refer to a more equipped center, and parental coercion. The third section surveyed the reasons for self-discharge related to the treatment staff, such as non-attendance of the physician on time, inappropriate behavior of the phycision and failure to answer the patient’s questions, inappropriate behavior of other medical staff, dissatisfaction with the diagnostic and treatment measures, delay in treatment, request for additional fees by phycision or staff, or lack of nursing staff. Finally, the fourth section surveyed the reasons for self-discharge related to dissatisfaction with the hospital’s physical environment, such as the lack of available ICU beds, failure of diagnostic equipment, the educational nature of the hospital, improper accommodation of companions, improper feeding, and lack of cleanliness.

Data were analyzed in SPSS software version 18. Quantitative variables were presented using descriptive statistics such As Mean±SD, Whereas qualitative variables were presented using frequency and percentage. To assess the associations between categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. Additionally, binary logistic regression analysis was employed to find the factors predicting self-discharge. Variables with P<0.2 in the univariate regression analysis were entered into the multivariable regression model. Statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

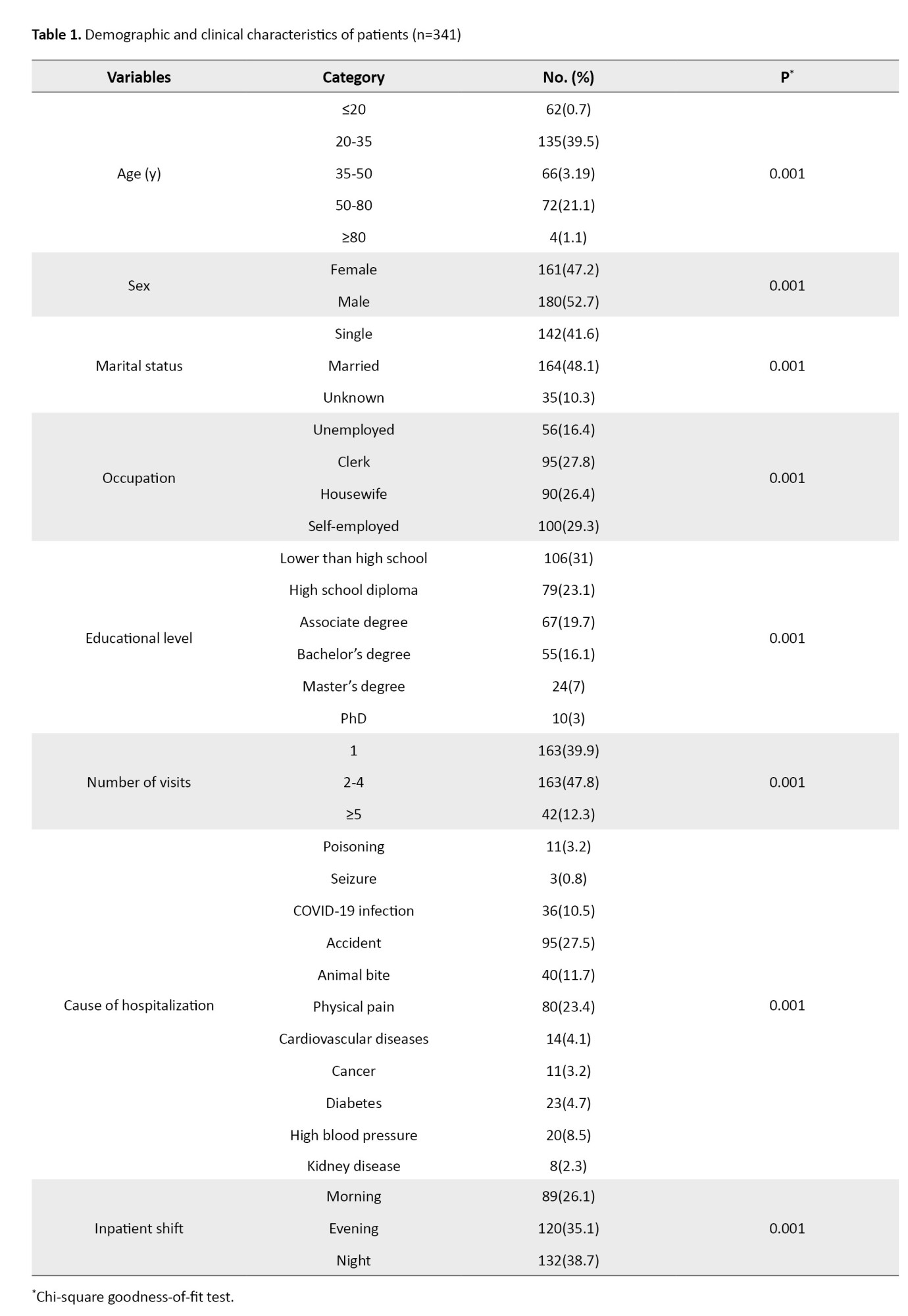

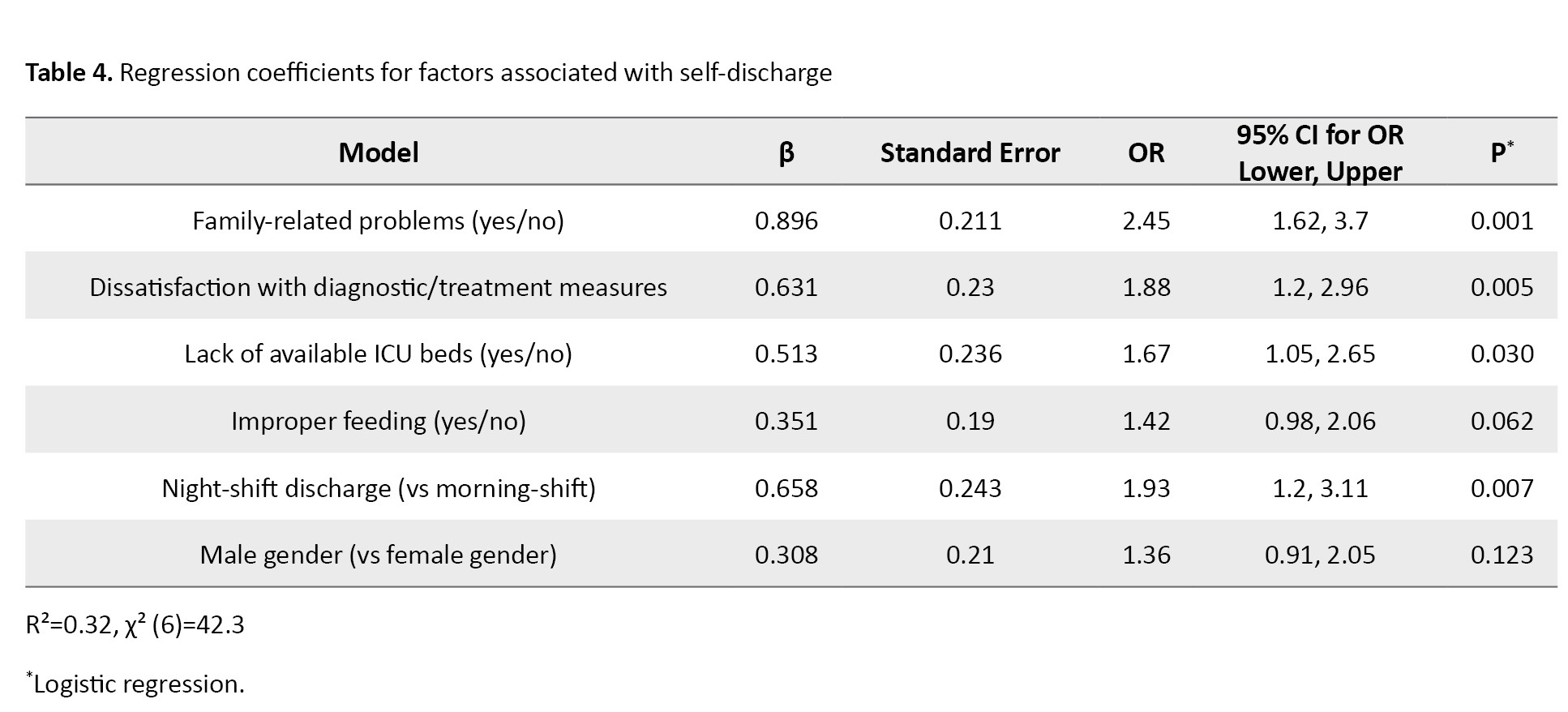

The mean age of the participants was 36.65±19.3 years. Among participants, 52.7% were male and 47.2% were female. Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and the results of the chi-square goodness-of-fit test for assessing whether each variable significantly comes from a specified distribution.

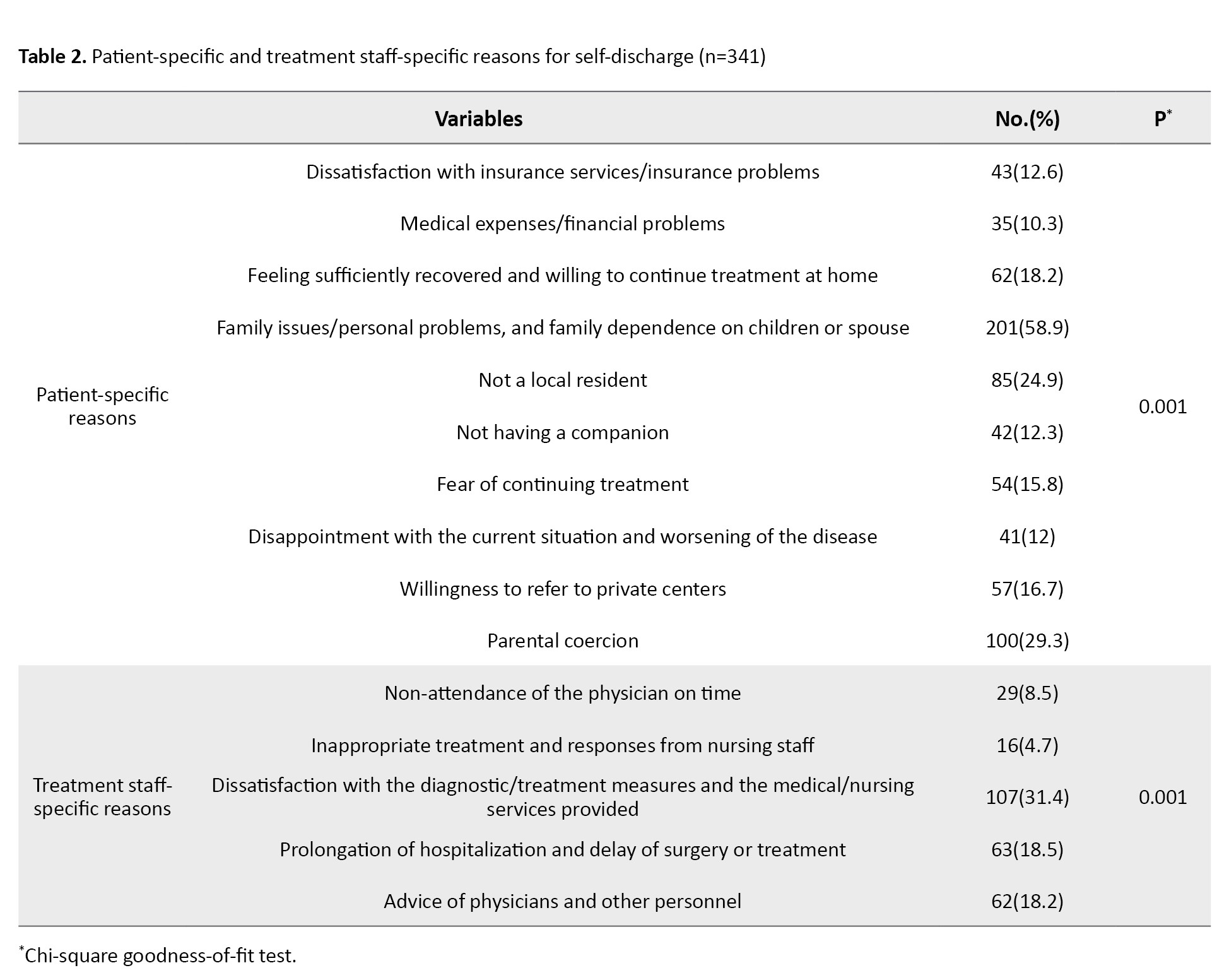

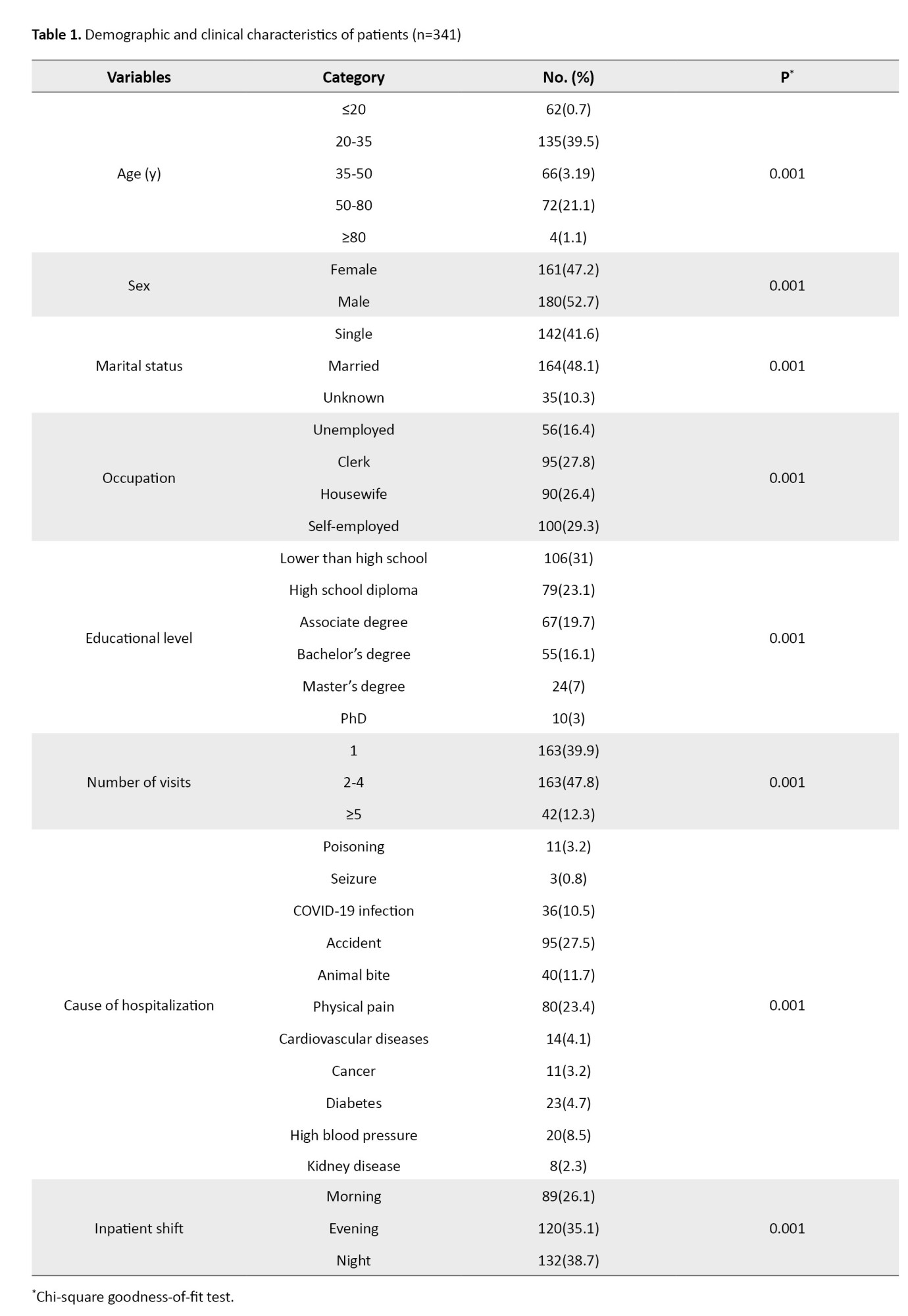

Table 2 shows the patient-specific and treatment staff-specific reasons for self-discharge and the results of the chi-square goodness-of-fit test.

Various patient-specific factors contributed to the decision of patients for self-discharge, such as dissatisfaction with insurance services/insurance problems (12.6%), high treatment costs/ financial problems (10.3%), feeling sufficiently recovered and intention to continue therapy at home (18.2%), family/personal problems and family dependence on children or spouse (58.9%), not being a local resident (24.9%), not having a companion (12.3%), fear of continuing treatment (15.8%), intention to seek treatment in private centers (16.7%), and parental coercion (29.3%).

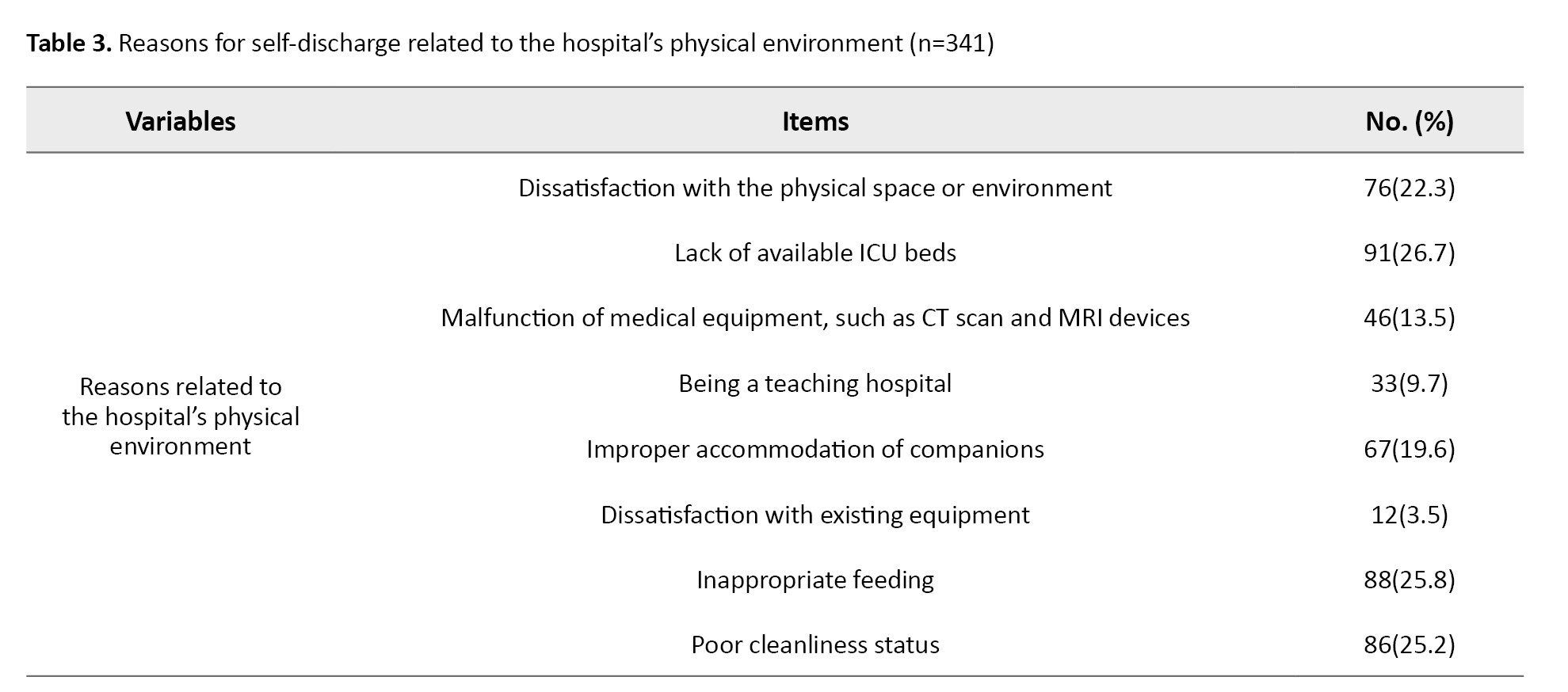

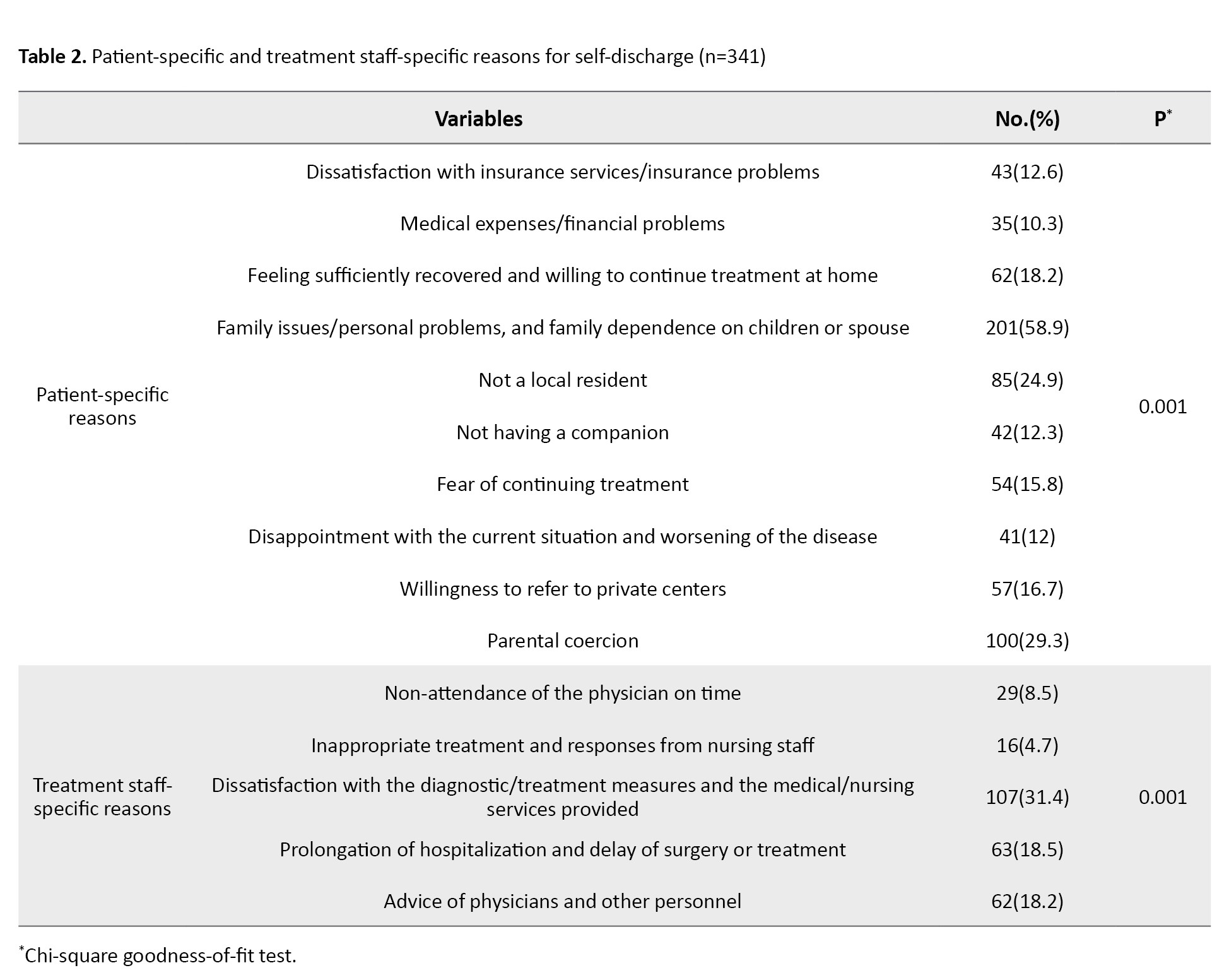

Regarding the treatment staff-specific reasons, 107 (31.4%) patients were dissatisfied with diagnostic/therapeutic measures and medical/nursing services provided, while 63 patients (18.5%) experienced prolonged hospitalization and delayed surgery or treatment. Table 3 provides information on the reasons for self-discharge related to the hospital.

As can be seen, 76 patients (22.3%) reported dissatisfaction with the physical space or environment of the hospital, 91(26.7%) could not find available ICU beds, and 46(13.5%) experienced malfunction of medical equipment, such as CT scan and MRI devices. Other reasons included inappropriate accommodation of companions (19.6%), improper feeding (25.8%), and poor cleanliness status (25.2%).

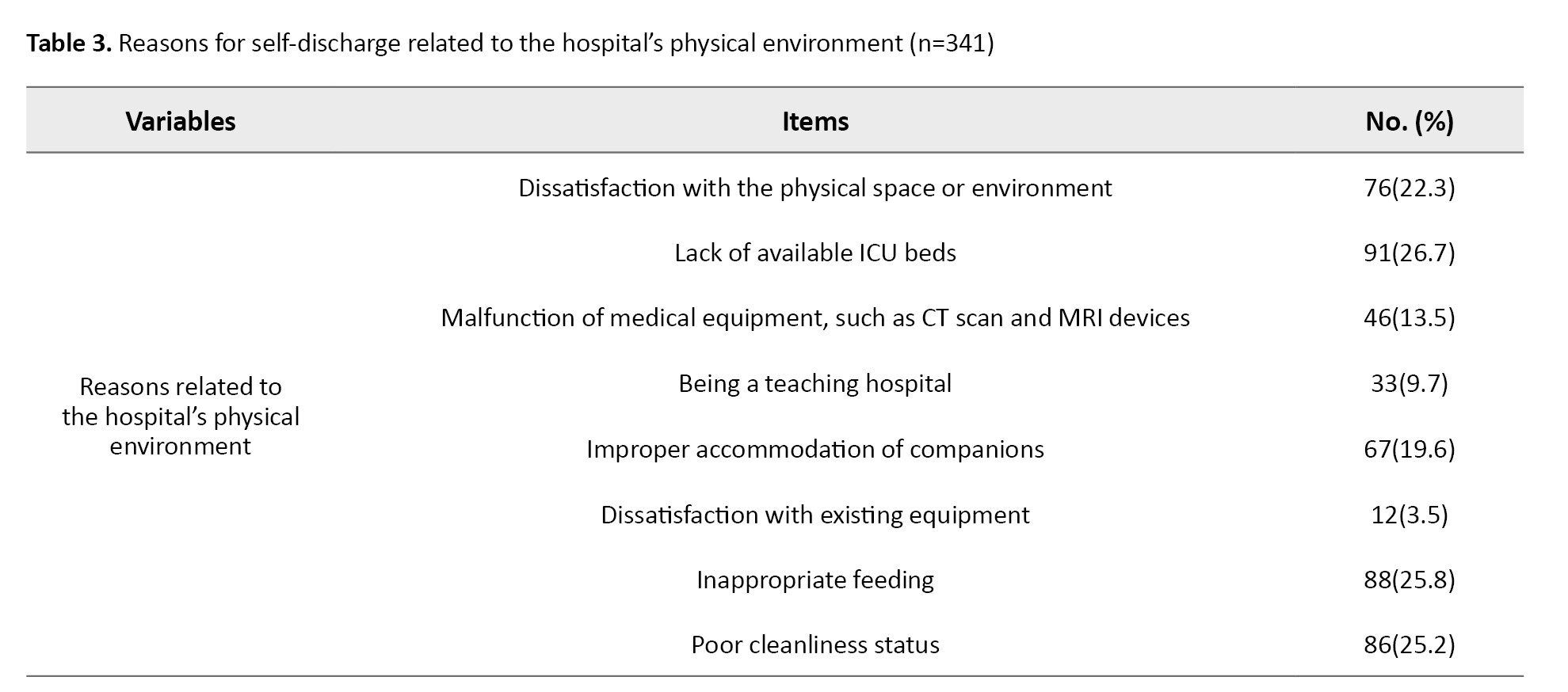

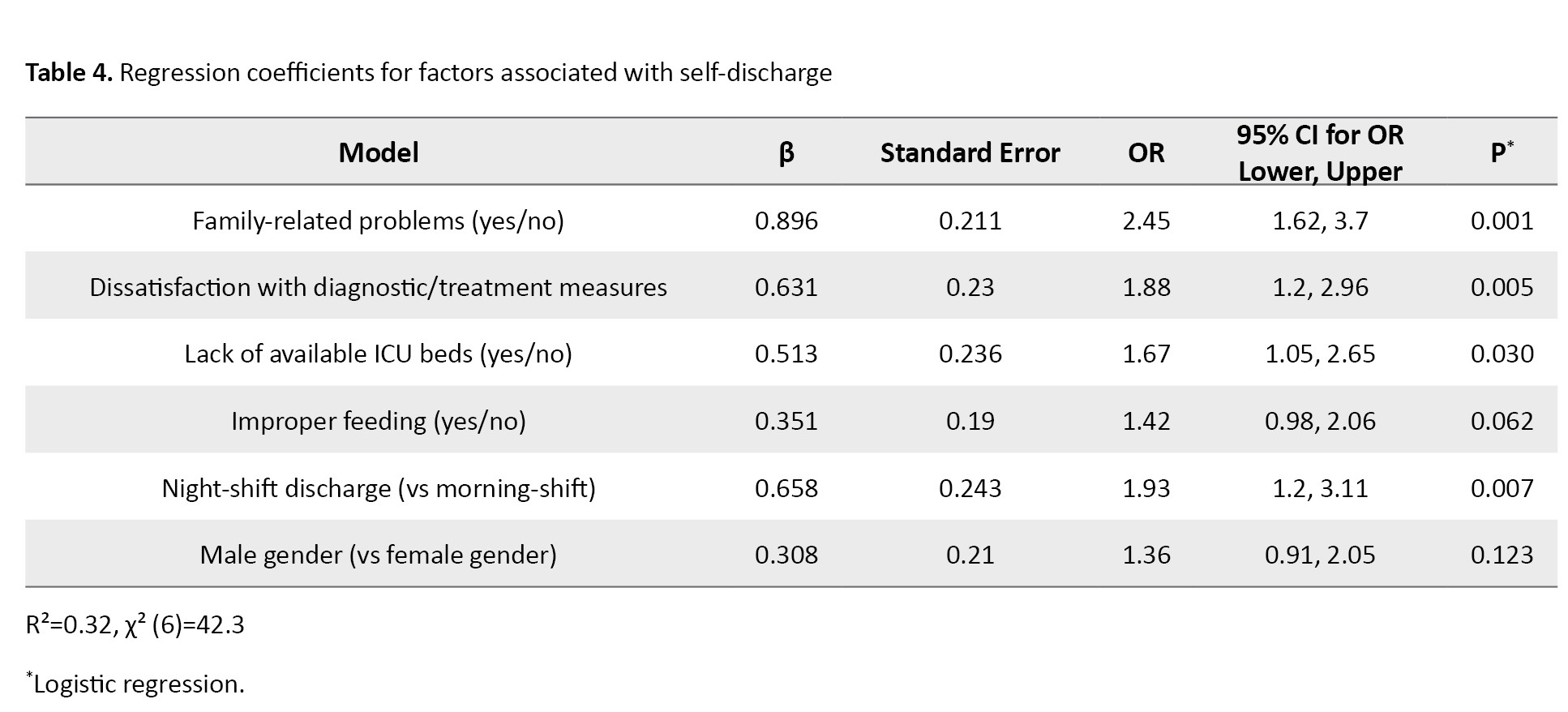

In the logistic regression analysis, several factors were found to be significantly associated with voluntary discharge. Patients with family-related problems were more likely to voluntarily discharge from the hospital compared to others (OR=2.45, 95% CI; 1.62%, 3.7%, P=0.001). Dissatisfaction with diagnostic/therapeutic measures (OR=1.88, 95% CI; 1.25%, 2.82%, P=0.005), lack of available ICU beds (OR=1.67, 95% CI; 1.05%, 2.66%, P=0.030), and discharge during night shifts (OR=1.93, 95% CI; 1.21%, 3.09%, P=0.007) were also significant predictors. Improper feeding (P=0.062) and male gender (P=0.123) were not significant predictors of self-discharge (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, most patients with self-discharge from the study hospital were young married male adults with lower than high school education. The majority had insurance (mostly social security insurance). These findings are consistent with the findings of Halvaei et al. [12]. In Mohammadi Kojidi’s study on patients who were discharged against medical advice from the emergency department, it was also found that 60.9% of patients were male, aged 26-35 years, with an education lower than a high school diploma [13]. These demographic characteristics may help guide the development of interventions to improve patient satisfaction and healthcare outcomes in hospitals to avoid self-discharge of patients. We found that most of the self-discharge cases occurred during the night shifts, compared to the evening and morning shifts, consistent with Halvaei et al.’s findings [12]. They also found that dissatisfaction with care and treatment quality in hospitals was significantly higher during the night shift, which may explain the higher number of self-discharges. Piri et al. also revealed that patients’ dissatisfaction with nursing and medical services, particularly during the night shift, was the primary reason for their dissatisfaction. Additionally, the majority of discharged patients had not fully recovered and opted to seek further treatment at other medical centers [14]. Baksi et al. [15] also reported that patients in the morning shift and during non-holiday periods had a lower probability of being discharged with personal consent. They suggested that self-discharge is a complex issue and depends on various factors, including patient-related, structural, and treatment-related factors. In contrast, Ravanshad et al. showed that the highest percentage of patient discharges occurred during the evening shift, followed by the morning and night shifts [16]. This discrepancy may be related to differences in the study setting, self-discharge reasons, and the clinical status of patients.

The present study demonstrated that the primary reasons for self-discharge were related to the patient (e.g. family issues/personal problems, and dependence on children or spouse), treatment staff (e.g. dissatisfaction with diagnostic/therapeutic measures and medical/nursing services), and the hospital conditions (e.g. lack of available ICU beds). Consistent with these findings, Mohammadi Kojidi et al. also identified several reasons for discharge against medical advice [13]. Rangraz’s study revealed that the rate of patients with self-discharge in Iran was higher compared to that in other countries, with the primary reason being issues related to the patients [17]. Ravanshad et al.’s study identified several reasons, including dissatisfaction with the medical staff, family issues, overcrowding in hospital wards, the intention to continue the treatment process at home, the hospital’s distance from the place of residence, high treatment costs, specific issues, lack of improvement, and health concerns [16]. Halvaei et al. reported reasons such as personal problems, dissatisfaction with the hospital facilities and equipment, and the lack of available beds [12]. Ravanpoor et al. identified individual factors, such as a preference for continuing treatment at home, concerns about the treatment environment, and dissatisfaction with the hospital ward’s physical space, as the primary reasons for patients’ self-discharge [18]. Our findings are also consistent with those of Jackson et al., who highlighted the importance of nurses’ and doctors’ polite and appropriate behavior towards patients. Such behaviors foster patient attraction and cooperation during treatment and follow-up stages, and motivate patients to recommend the doctor to others [19]. Vahdat et al.’s survey of patient satisfaction in hospitals in Mashhad, Iran, revealed that many patients were dissatisfied with the availability of doctors and the quality of their services. They found that patients’ satisfaction with doctors’ and nurses’ educational levels and the quality of their services were directly related to each other [20]. In other studies, the primary reasons were inadequate understanding of the patient’s health status, financial problems, family issues, lack of attention from doctors and nurses, inappropriate treatment of patients by the healthcare team, and failure to receive timely care [21], patients’ perception of recovery, and alcohol addiction [22].

Based on the logistic regression model, family-related problems, dissatisfaction with diagnostic and therapetic measures, lack of available ICU beds, and night-shift discharge were identified as the factors predicting self-discharge in patients. Considering these factors, some strategies should be implemented to improve communication, accessibility, and support, motivating patients to change their attitude toward self-discharge from the hospital, especially during night shifts. These modifications may not only minimize the likelihood of early discharge but also its negative implications.

While this study provided valuable insights into patients’ reasons for self-discharging from emergency departments of hospitals, it also had limitations that should be considered. Firstly, the descriptive design of the study limits the ability to establish causality between the factors and patient satisfaction. Additionally, the study was conducted in a single hospital in Jiroft city, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other hospitals and cities. The reliance on self-reported data is another limitation of the study, as it may be subject to response bias and fail to reflect patients’ experiences accurately. Finally, the study did not explore the impact of cultural and social factors on patient satisfaction, which could be an essential consideration in healthcare settings. The findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions to reduce self-discharge by addressing patient-related, treatment staff-related, and hospital-related causes. Also, regular staff training, patient counseling, and continuous quality improvement activities, such as audits and satisfaction surveys, can enhance care quality and reduce the likelihood of self-discharge in patients.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran (Code: IR.JMU.REC.1401.019). All ethical guidelines and regulations were followed throughout the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before completing the study checklist, and participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information and the voluntary nature of their participation.

Funding

This research was funded by Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, review and editing: Salman Daneshi and Vahid Rahmanian; Data collection, administration, and writing the original draft: Shima Groohi-Sardou, Akbar Anaei Goudari, Najmeh Ghasemian, Ehsan Goroei Sardou; Data analysis and interpretation: Vahid Rahmanian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the managers and staff of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Jiroft for their kind cooperation and for facilitating this study, as well as all patients who voluntarily participated.

Patients have the right to enter or leave the treatment centers with their consent and without the need for the treatment staff’s permission, but it is better for them to complete their treatment process and be discharged by the attending physician. Patient-initiated discharge can lead to adverse outcomes such as re-hospitalization, death, and increased hospital costs [1-3]. This topic is crucial in the emergency departments and Intensive Care Units (ICUs), as patients’ lives may be at risk. Patients who are discharged by personal consent often have acute illnesses with severe symptoms at the time of discharge [4, 5], and their prognosis is generally more unfavorable than that of patients discharged with the doctor’s approval [6]. Investigating the rate of patient-initiated discharge without completing the treatment process can be a measure of patient satisfaction with the treatment environment and system. To improve conditions and reduce the number of patients leaving the hospital with personal consent before completing their treatment, it is essential to identify the reasons for self-discharge and take steps to increase patient satisfaction [4, 6]. Patient-initiated discharge is the strongest predictor of readmission in the first 15 days after discharge; 21% of patients discharged by personal consent readmit within this period, and the rate of readmission in the first 7 days is 14% for these patients, compared to other patients (7%) [7].

According to statistics, there is a notable contradiction in the rate of patients with self-discharge between developed countries (such as the United States) and Iran. In the United States, it accounts for 0.8-2.2% of all discharge cases, particularly in teaching hospitals. However, in Iran, the rate is higher, ranging from 3% in mental hospitals to 20% in emergency departments [8]. Assessing the level of patient satisfaction in hospitals and identifying the underlying causes are fundamental steps toward enhancing the quality of medical services [9, 10]. Patient satisfaction with medical care is an essential indicator of the perceived quality of care. Low patient satisfaction can lead to poor cooperation with treatment staff, resulting in resource waste and diminished clinical outcomes. As a result, meeting patients’ needs and ensuring their satisfaction should be a primary goal across all forms of medical care. It should be regarded as an essential outcome measure [11]. Overall, self-discharge from a hospital can occur for various reasons, such as patient dissatisfaction with hospital services, delayed medical attention, high medical costs, personal and familial reasons, and inadequate hospital facilities and environment. The present study aimed to investigate the reasons for self-discharge from the emergency departments in Jiroft, Iran.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional and analytical study was conducted in 2022. Using a census method, all 341 patients discharged with personal consent from the emergency department of a teaching hospital affiliated with Jiroft University of Medical Sciences were included. The sample size was calculated based on a total population of approximately 3,000 individuals, using the single-population proportion formula. Due to the unknown proportion (p) in the study population, P=0.5 was assumed to yield the maximum required sample size. The confidence level was set at 95%, and the margin of error (d) was set at 0.05. Based on these parameters, the final sample size was estimated to be 341. The inclusion criterion was voluntary discharge from the emergency department of the study hospital. The exclusion criterion was unconsciousness or lack of cooperation to complete the checklist.

The data collection tool was a researcher-made checklist approved by five specialists. It had four sections. The first section surveyed the demographic characteristics of the patients. The second section surveyed the reasons for self-discharge related to patients, such as feeling sufficiently recovered, intention to continue treatment at home, family issues, dependence on children and spouse, not being a local resident, fear of ongoing therapy, loss of hope in recovery from disease, intention to refer to a more equipped center, and parental coercion. The third section surveyed the reasons for self-discharge related to the treatment staff, such as non-attendance of the physician on time, inappropriate behavior of the phycision and failure to answer the patient’s questions, inappropriate behavior of other medical staff, dissatisfaction with the diagnostic and treatment measures, delay in treatment, request for additional fees by phycision or staff, or lack of nursing staff. Finally, the fourth section surveyed the reasons for self-discharge related to dissatisfaction with the hospital’s physical environment, such as the lack of available ICU beds, failure of diagnostic equipment, the educational nature of the hospital, improper accommodation of companions, improper feeding, and lack of cleanliness.

Data were analyzed in SPSS software version 18. Quantitative variables were presented using descriptive statistics such As Mean±SD, Whereas qualitative variables were presented using frequency and percentage. To assess the associations between categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. Additionally, binary logistic regression analysis was employed to find the factors predicting self-discharge. Variables with P<0.2 in the univariate regression analysis were entered into the multivariable regression model. Statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 36.65±19.3 years. Among participants, 52.7% were male and 47.2% were female. Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and the results of the chi-square goodness-of-fit test for assessing whether each variable significantly comes from a specified distribution.

Table 2 shows the patient-specific and treatment staff-specific reasons for self-discharge and the results of the chi-square goodness-of-fit test.

Various patient-specific factors contributed to the decision of patients for self-discharge, such as dissatisfaction with insurance services/insurance problems (12.6%), high treatment costs/ financial problems (10.3%), feeling sufficiently recovered and intention to continue therapy at home (18.2%), family/personal problems and family dependence on children or spouse (58.9%), not being a local resident (24.9%), not having a companion (12.3%), fear of continuing treatment (15.8%), intention to seek treatment in private centers (16.7%), and parental coercion (29.3%).

Regarding the treatment staff-specific reasons, 107 (31.4%) patients were dissatisfied with diagnostic/therapeutic measures and medical/nursing services provided, while 63 patients (18.5%) experienced prolonged hospitalization and delayed surgery or treatment. Table 3 provides information on the reasons for self-discharge related to the hospital.

As can be seen, 76 patients (22.3%) reported dissatisfaction with the physical space or environment of the hospital, 91(26.7%) could not find available ICU beds, and 46(13.5%) experienced malfunction of medical equipment, such as CT scan and MRI devices. Other reasons included inappropriate accommodation of companions (19.6%), improper feeding (25.8%), and poor cleanliness status (25.2%).

In the logistic regression analysis, several factors were found to be significantly associated with voluntary discharge. Patients with family-related problems were more likely to voluntarily discharge from the hospital compared to others (OR=2.45, 95% CI; 1.62%, 3.7%, P=0.001). Dissatisfaction with diagnostic/therapeutic measures (OR=1.88, 95% CI; 1.25%, 2.82%, P=0.005), lack of available ICU beds (OR=1.67, 95% CI; 1.05%, 2.66%, P=0.030), and discharge during night shifts (OR=1.93, 95% CI; 1.21%, 3.09%, P=0.007) were also significant predictors. Improper feeding (P=0.062) and male gender (P=0.123) were not significant predictors of self-discharge (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, most patients with self-discharge from the study hospital were young married male adults with lower than high school education. The majority had insurance (mostly social security insurance). These findings are consistent with the findings of Halvaei et al. [12]. In Mohammadi Kojidi’s study on patients who were discharged against medical advice from the emergency department, it was also found that 60.9% of patients were male, aged 26-35 years, with an education lower than a high school diploma [13]. These demographic characteristics may help guide the development of interventions to improve patient satisfaction and healthcare outcomes in hospitals to avoid self-discharge of patients. We found that most of the self-discharge cases occurred during the night shifts, compared to the evening and morning shifts, consistent with Halvaei et al.’s findings [12]. They also found that dissatisfaction with care and treatment quality in hospitals was significantly higher during the night shift, which may explain the higher number of self-discharges. Piri et al. also revealed that patients’ dissatisfaction with nursing and medical services, particularly during the night shift, was the primary reason for their dissatisfaction. Additionally, the majority of discharged patients had not fully recovered and opted to seek further treatment at other medical centers [14]. Baksi et al. [15] also reported that patients in the morning shift and during non-holiday periods had a lower probability of being discharged with personal consent. They suggested that self-discharge is a complex issue and depends on various factors, including patient-related, structural, and treatment-related factors. In contrast, Ravanshad et al. showed that the highest percentage of patient discharges occurred during the evening shift, followed by the morning and night shifts [16]. This discrepancy may be related to differences in the study setting, self-discharge reasons, and the clinical status of patients.

The present study demonstrated that the primary reasons for self-discharge were related to the patient (e.g. family issues/personal problems, and dependence on children or spouse), treatment staff (e.g. dissatisfaction with diagnostic/therapeutic measures and medical/nursing services), and the hospital conditions (e.g. lack of available ICU beds). Consistent with these findings, Mohammadi Kojidi et al. also identified several reasons for discharge against medical advice [13]. Rangraz’s study revealed that the rate of patients with self-discharge in Iran was higher compared to that in other countries, with the primary reason being issues related to the patients [17]. Ravanshad et al.’s study identified several reasons, including dissatisfaction with the medical staff, family issues, overcrowding in hospital wards, the intention to continue the treatment process at home, the hospital’s distance from the place of residence, high treatment costs, specific issues, lack of improvement, and health concerns [16]. Halvaei et al. reported reasons such as personal problems, dissatisfaction with the hospital facilities and equipment, and the lack of available beds [12]. Ravanpoor et al. identified individual factors, such as a preference for continuing treatment at home, concerns about the treatment environment, and dissatisfaction with the hospital ward’s physical space, as the primary reasons for patients’ self-discharge [18]. Our findings are also consistent with those of Jackson et al., who highlighted the importance of nurses’ and doctors’ polite and appropriate behavior towards patients. Such behaviors foster patient attraction and cooperation during treatment and follow-up stages, and motivate patients to recommend the doctor to others [19]. Vahdat et al.’s survey of patient satisfaction in hospitals in Mashhad, Iran, revealed that many patients were dissatisfied with the availability of doctors and the quality of their services. They found that patients’ satisfaction with doctors’ and nurses’ educational levels and the quality of their services were directly related to each other [20]. In other studies, the primary reasons were inadequate understanding of the patient’s health status, financial problems, family issues, lack of attention from doctors and nurses, inappropriate treatment of patients by the healthcare team, and failure to receive timely care [21], patients’ perception of recovery, and alcohol addiction [22].

Based on the logistic regression model, family-related problems, dissatisfaction with diagnostic and therapetic measures, lack of available ICU beds, and night-shift discharge were identified as the factors predicting self-discharge in patients. Considering these factors, some strategies should be implemented to improve communication, accessibility, and support, motivating patients to change their attitude toward self-discharge from the hospital, especially during night shifts. These modifications may not only minimize the likelihood of early discharge but also its negative implications.

While this study provided valuable insights into patients’ reasons for self-discharging from emergency departments of hospitals, it also had limitations that should be considered. Firstly, the descriptive design of the study limits the ability to establish causality between the factors and patient satisfaction. Additionally, the study was conducted in a single hospital in Jiroft city, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other hospitals and cities. The reliance on self-reported data is another limitation of the study, as it may be subject to response bias and fail to reflect patients’ experiences accurately. Finally, the study did not explore the impact of cultural and social factors on patient satisfaction, which could be an essential consideration in healthcare settings. The findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions to reduce self-discharge by addressing patient-related, treatment staff-related, and hospital-related causes. Also, regular staff training, patient counseling, and continuous quality improvement activities, such as audits and satisfaction surveys, can enhance care quality and reduce the likelihood of self-discharge in patients.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran (Code: IR.JMU.REC.1401.019). All ethical guidelines and regulations were followed throughout the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before completing the study checklist, and participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information and the voluntary nature of their participation.

Funding

This research was funded by Jiroft University of Medical Sciences, Jiroft, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, review and editing: Salman Daneshi and Vahid Rahmanian; Data collection, administration, and writing the original draft: Shima Groohi-Sardou, Akbar Anaei Goudari, Najmeh Ghasemian, Ehsan Goroei Sardou; Data analysis and interpretation: Vahid Rahmanian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the managers and staff of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Jiroft for their kind cooperation and for facilitating this study, as well as all patients who voluntarily participated.

References

- Albayati A, Douedi S, Alshami A, Hossain MA, Sen S, Buccellato V, et al. Why do patients leave against medical advice? Reasons, consequences, prevention, and interventions. Healthcare. 2021; 9(2):111. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare9020111] [PMID]

- Bayor S, Kojo Korsah A. Discharge against Medical Advice at a Teaching Hospital in Ghana. Nurs Res Pract. 2023; 2023:4789176. [DOI:10.1155/2023/4789176] [PMID]

- Babaei Z, Alizadeh M, Shahsawari S, Jihoni-Kalhori A, Cheraghbeigi R, Sotoudeh R, et al. Analysis of factors affecting discharge with the personal consent of hospitalized patients: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2023 ; 6(8):e1447. [DOI:10.1002/hsr2.1447] [PMID]

- Mahdipour S, Shahrokhi Rad R, Naghdipour Mirsadeghi M, Biazar G, Javanak M, et al. Discharge Against Medical Advice from Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and Some Influencing Factors in an Academic Center. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2024; 26(2):e135409. [DOI:10.5812/zjrms-135409]

- Monfared A, Javadi-Pashaki N, Dehghan Nayeri N, Jafaraghaee F. Barriers and facilitators of readiness for hospital discharge in patients with myocardial infarction: A qualitative study-quality improvement study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2024; 86(4):1967-76.[DOI:10.1097/MS9.0000000000001706] [PMID]

- Masaeli M, Nasouhi S, Shahabian M. [Reduced discharge against medical advice at the emergency department of Be’sat Hospital in Tehran (Persian)]. EBNESINA. 2019; 21(1):54-6.[DOI:10.22034/21.1.54]

- Tan SY, Feng JY, Joyce C, Fisher J, Mostaghimi A. Association of hospital discharge against medical advice wit h readmission and in-hospital mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(6):e206009-. [DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6009] [PMID]

- Eaton EF, Westfall AO, McClesky B, Paddock CS, Lane PS, Cropsey KL, et al. In-hospital illicit drug use and patient-directed discharge: Barriers to care for patients with injection-related infections. IOpen Forum Infect Dis. 2020; 7(3):ofaa074. [DOI:10.1093/ofid/ofaa074] [PMID]

- Abuzeyad FH, Farooq M, Alam SF, Ibrahim MI, Bashmi L, Aljawder SS, et al. Discharge against medical advice from the emergency department in a university hospital. BMC Emerg Med. 2021; 21(1):31. [DOI:10.1186/s12873-021-00422-6] [PMID]

- Harun NA, Finlay AY, Piguet V, Salek S. Understanding clinician influences and patient perspectives on outpatient discharge decisions: A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(3):e010807. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010807] [PMID]

- Alibrandi A, Gitto L, Limosani M, Mustica PF. Patient satisfaction and quality of hospital care. Eval Program Plann. 2023; 97:102251. [DOI:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2023.102251] [PMID]

- Rouhbakhsh Halvaei S, Sheikh Motahar Vahedi H, Ahmadi A, Mousavi MS, Parsapoor A, Sima AR, et al. Rate and causes of discharge against medical advice from a university hospital emergency department in Iran: An ethical perspective. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2020; 13:15. [DOI:10.18502/jmehm.v13i15.4391] [PMID]

- Mohammadi Kojidi H, Fayazi H, Badsar A, Rostamali N, Attarchi M. [Assessment of the causes of discharge against medical advice in hospitalized patients in emergency department (Persian)]. J Guilan Univ Med Sci. 2020; 29(1):33-42. [Link]

- Zohoor A, Piri Z. Patients satisfaction with provided services in the Akbarabady hospital in 2003. J Res Health Sci. 2003; 3(1):29-34.[Link]

- Baksi A, Arda Sürücü H, I Nal G. Postcraniotomy patients' readiness for discharge and predictors of their readiness for discharge. J Neurosci Nurs. 2020; 52(6):295-9. [DOI:10.1097/JNN.0000000000000554] [PMID]

- Ravanshad Y, Golsorkhi M, Bakhtiari E, Keykhosravi AL, Azarfar A, Shoja M, et al. [Evaluation of causes and outcomes of discharge with the personal consent of patients admitted to Dr. Sheikh Hospital of Mashhad (Persian)]. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 2021; 28:183-8. [Link]

- Rangraz Jeddi F, Rangraz Jeddi M, Rezaeiimofrad M. [Patients’ reasons for discharge against medical advice in university hospitals of Kashan University of Medical Sciences in 2008 (Persian)]. Hakim Res J. 2010; 13(1):33-9. [Link]

- Ravanipour M, Tavasolnia S, Jahanpour F, Hoseini S. [Appointment of important causes of discharge against medical advice in patients in Gachsaran Rajaii hospital in primary 6 months of 2013 (Persian)]. J Educ Ethics Nurs. 2014; 3(1):1-7. [Link]

- Jackson JL, Chamberlin J, Kroenke K. Predictors of patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med. 2001; 52(4):609-20. [DOI:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00164-7] [PMID]

- Vahdat S, Hesam S, Mehrabian F. [Affecting factors of patient discharge with personal satisfaction in Ghazvin Rajaei Medical Educational Center (Persian)]. J Guilan Univ Med Sci. 2010; 20(2):47-52.[Link]

- Baptist AP, Warrier I, Arora R, Ager J, Massanari RM. Hospitalized patients with asthma who leave against medical advice: Characteristics, reasons, and outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 119(4):924-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.695] [PMID]

- Gavurova B, Dvorsky J, Popesko B. Patient satisfaction determinants of inpatient healthcare. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11337. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph182111337] [PMID]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2024/01/20 | Accepted: 2026/01/11 | Published: 2026/01/11

Received: 2024/01/20 | Accepted: 2026/01/11 | Published: 2026/01/11

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |