Tue, Feb 3, 2026

Volume 34, Issue 1 (1-2024)

JHNM 2024, 34(1): 71-81 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ravi R, Ramesh M, Chalasani S H, Mathias J, Kulkarni P. Barriers and Facilitators of Voluntary Medication Errors Reporting According to the Nursing Staff in India. JHNM 2024; 34 (1) :71-81

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2250-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2250-en.html

1- Research Scholar, Department of Pharmacy Practice, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Mysuru, Karnataka, India.

2- Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Mysuru, Karnataka, India.

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Mysuru, Karnataka, India. ,sriharshachalasani@jssuni.edu.in

4- Deputy Chief of Nursing services, JSS Hospital, Mysuru, Karnataka, India.

5- Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, JSS Medical College and Hospital, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Mysuru, Karnataka, India.

2- Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Mysuru, Karnataka, India.

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Mysuru, Karnataka, India. ,

4- Deputy Chief of Nursing services, JSS Hospital, Mysuru, Karnataka, India.

5- Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, JSS Medical College and Hospital, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Mysuru, Karnataka, India.

Full-Text [PDF 450 kb]

(679 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1374 Views)

Full-Text: (683 Views)

Introduction

The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) has defined the medication error (ME) as “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing, order communication, product labelling, packaging and nomenclature, compounding, dispensing, distribution, administration, education, monitoring, and use” [1]. MEs have been estimated to cost 42 billion USD per year accounting for nearly 1% of total global health costs [2]. A study conducted in Australia found that 16.6% of all hospital admissions were associated with an avoidable adverse event, with nearly 5% of cases involving an iatrogenic injury leading to death. An 11% adverse event rate was reported by a retrospective study conducted in the United Kingdom (UK). Studies conducted in other countries have revealed comparable incidences of adverse events; one in New Zealand reported a rate of 10.7%, while another in Denmark reported a rate of 9% [3]. In a study conducted on hospitalized patients in Uttarakhand, India, the prevalence of MEs was reported to be 25.7% [4]. MEs can occur during prescribing, transcribing, dispensing, procurement, administration, and/or monitoring of a drug [5]. These errors can cause considerable negative outcomes, which not only affect the patients’ health but also cause unnecessary hospital re-admissions and prolongation of hospital stay. This drastically affects patient satisfaction and reduces their confidence in the healthcare system [6, 7].

Any member of the healthcare team can make MEs. Healthcare specialists in general and nurses in particular are responsible for reporting MEs. the MEs by nurses are most common, mainly because all prescribed medications are given by the nurses and they spend most of the time administering drugs to patients. Consequently, they should administer medications cautiously and prevent any incidence of medication errors [8, 9, 10, 11]. Thus, medication errors can hinder nursing care and cause a preventable harm to patients. Despite the rise in ME prevalence, most of them are often under-reported within the healthcare settings. The ME reporting should be a voluntary action to help reduce or prevent future mistakes that can cause patient damage. It can also reduce the associated financial and personal costs. Since ME reporting is an important patient safety criterion, identifying its facilitators and barriers is critical for patient safety investigation. This study aims to investigate the barriers and facilitators of voluntarily ME reporting among the nursing staff in India.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out for 6 months from May to October 2022. Out of 800 nurses, 511 nurses who were involved in ward round activities and were working in three work shifts from various specialities participated (286 nurses including interns, practical nurses, and nursing managers were excluded). Using a convenience sampling method, 398 nurses from among 511 nurses were included in the study (116 nurses did not enter in study as they did not respond to the questionnaire).

After a literature review, a questionnaire measuring the facilitators and barriers to reporting MEs was designed. It was a 39-items tool with four sections (demographic information, knowledge, barriers, and facilitators). The questionnaire was validated based on the opinions of 11 healthcare professionals (4 physicians, one chief nurse, and 6 charge nurses) by measuring the item-content validity index (I-CVI) and scale-content validity index (S-CVI). The overall I-CVI was 0.92. Since it was more than 80%, none of the items needed further change or removal. An average S-CVI score of 94.6% for Relevance, 93.2% for clarity, 94.2% for ambiguity, and 96.4% for simplicity were obtained. The Cronbach’s α value was obtained as 0.86, 0.88 and 0.87 for the knowledge, barriers, and facilitators subscales, respectively. The first section surveys the demographic characteristics of nurses (such as age, gender, working department, years of experience, and educational level). The second section consists of seven items measuring the knowledge of MEs and the reporting system; six items are answered by Yes (1 point) and No (0 points), and one item (assessing the number of MEs reported) is answered by “0 reports”, “1-5 reports”, and “more than 5 reports”. The third section with 27 items uses a Likert scale as 1=strongly agree, 2=agree, 3=disagree, 4=strongly disagree to surveys the barriers to voluntary reporting of MEs. The last section with 5 items rated on a Likert scale as 1=strongly agree, 2=agree, 3=disagree, 4=strongly disagree, surveys the facilitators of voluntary ME reporting

The questionnaire was prepared using the Google Form and the link was sent to the nursing staffs and their responses were collected. Chi-square test was used to determine if there is any significant difference among the nurse’s responses to each items of the subscales facilitators and barriers to determine their willingness to engage in voluntary ME reporting. All collected data were entered and analyzed in SPSS software, version 18. The variables such as age, gender, and educational level were described using the statistics of frequency and percentage.

Results

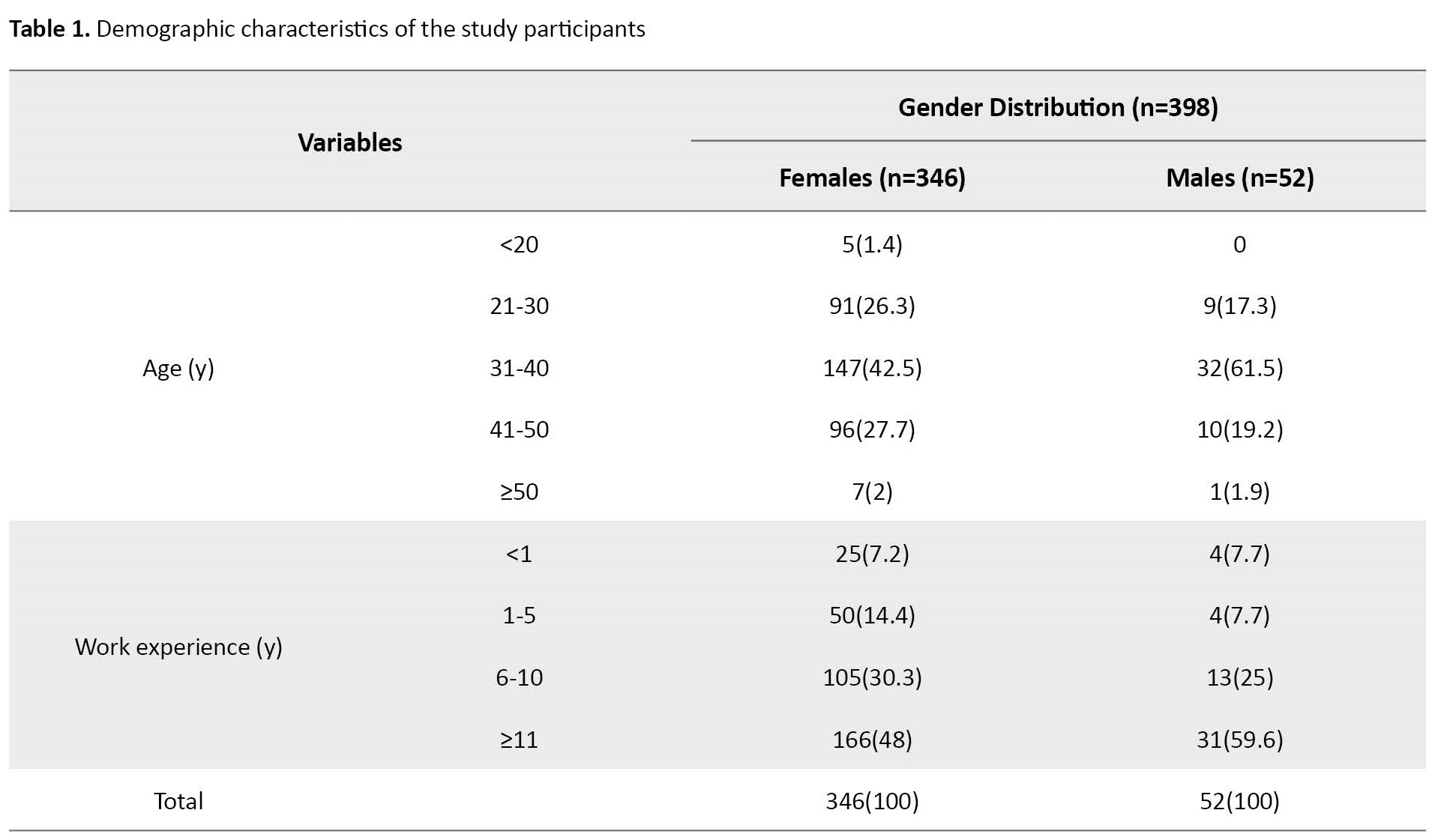

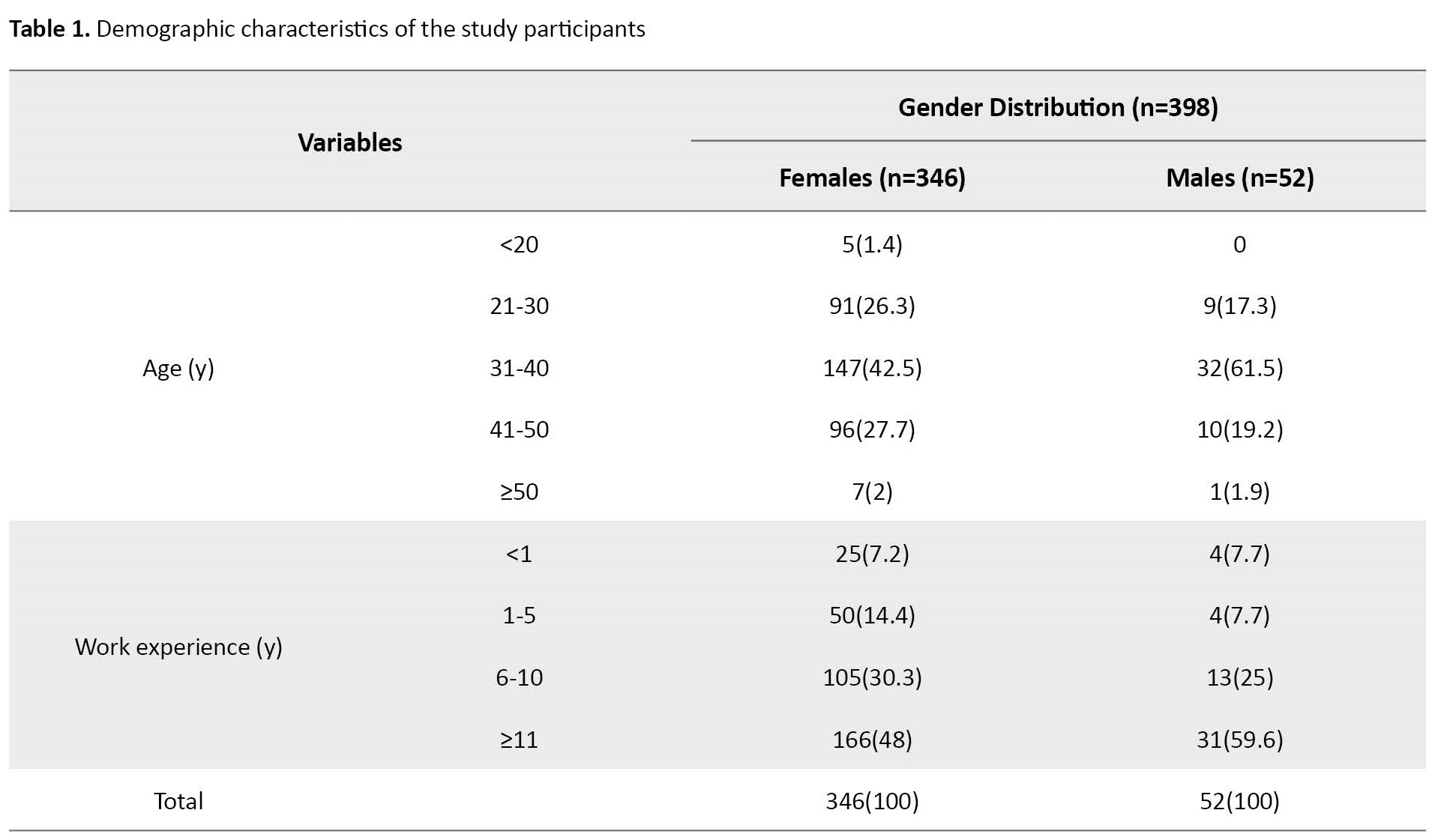

Of 511 nurses, 398 completed the questionnaires (response rate=77.9%), of whom 87% were female and 13% were male. The majority were at an age range of 31–40 years (44.9%). For more information, see Table 1.

The majority (85.67%) had a diploma, followed by 12.56% with a bachelor’s degree in nursing, and 1.75% with a master’s degree in nursing.

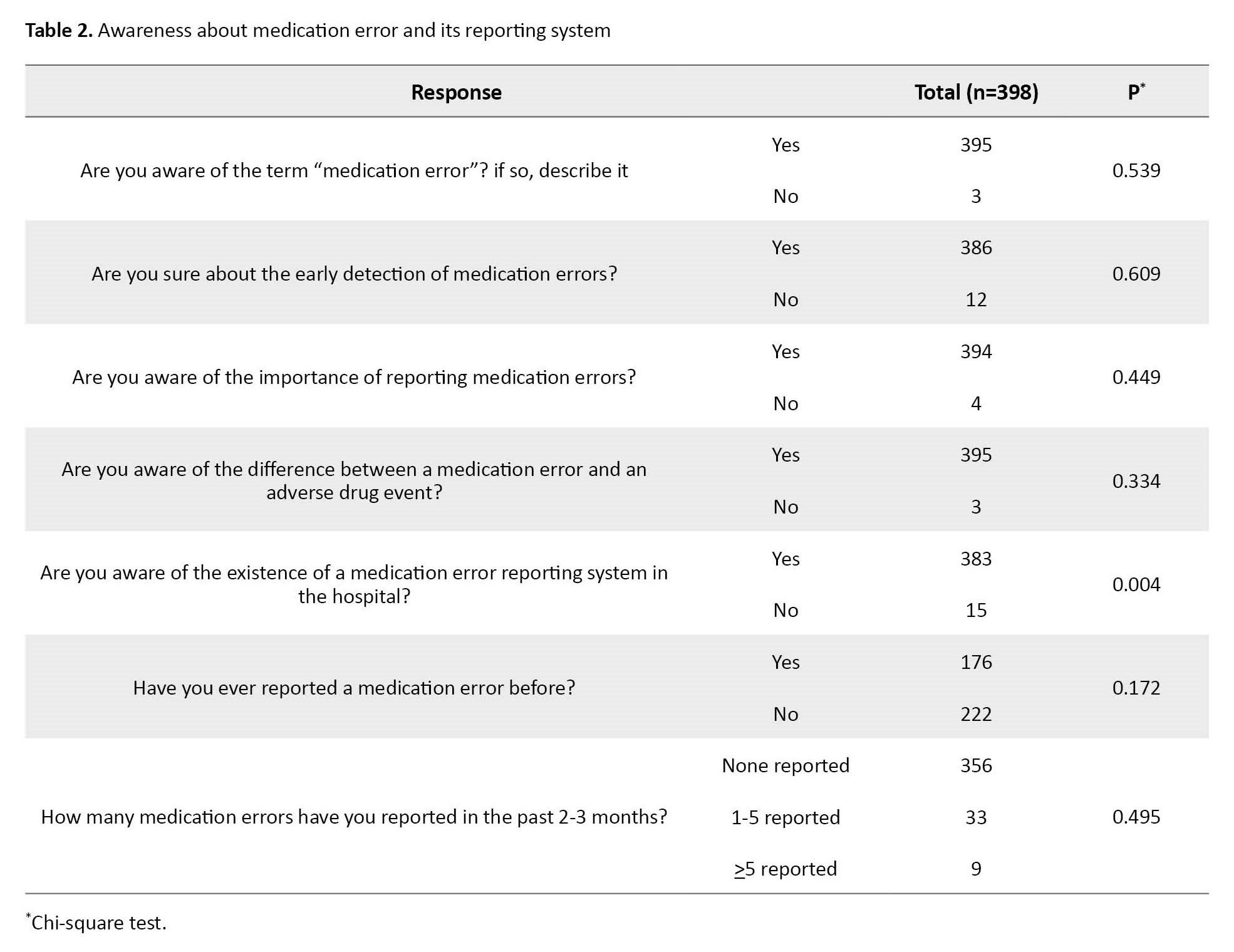

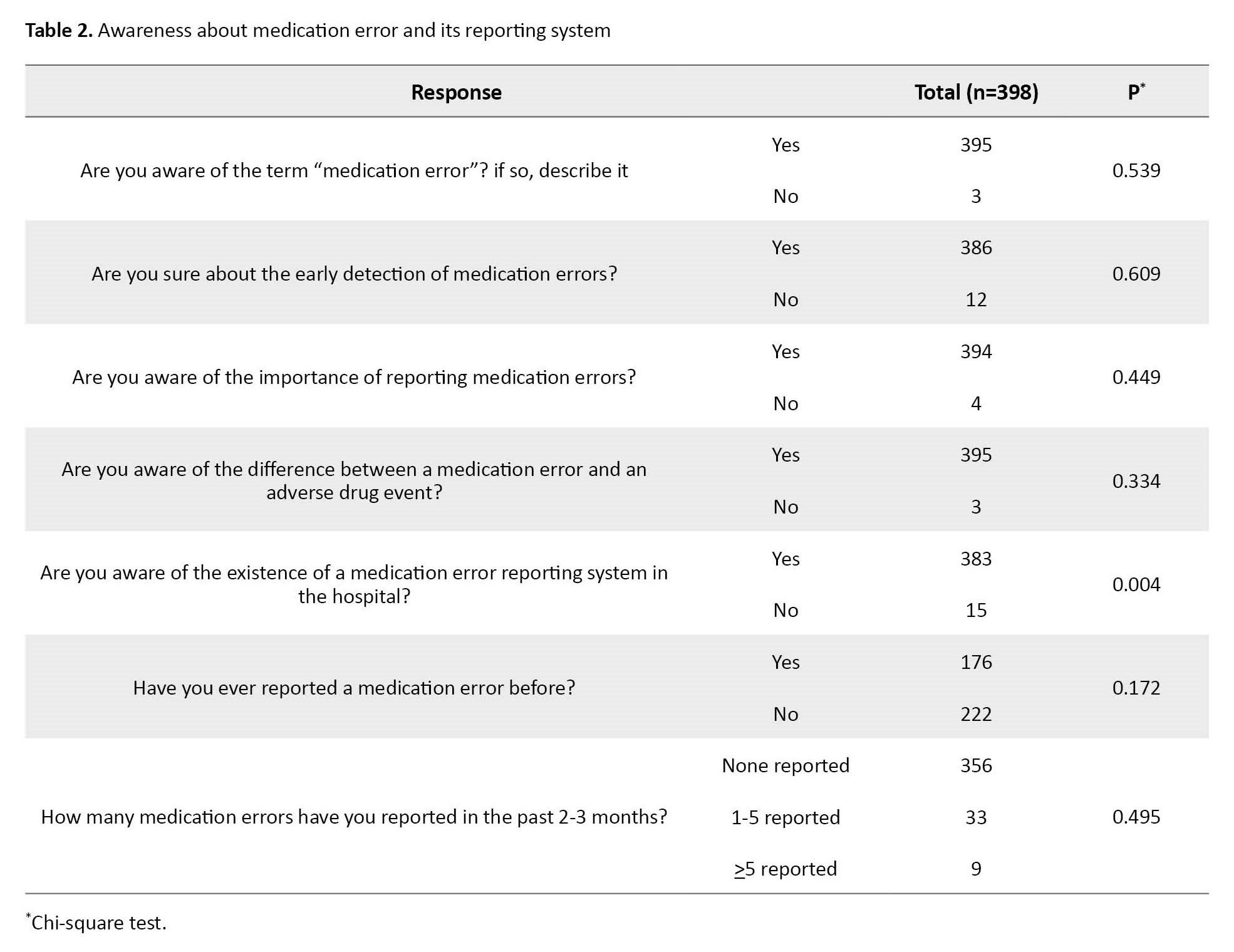

The results related to the knowledge of MEs, their impacts, and the reporting system showed that 96.2% had good knowledge, whereas 3.85% were unaware of the existence of a ME reporting system in the hospital and chi square test showed only ʹawareness of the existence of a medication error reporting system in the hospital was significant (P=0.004).

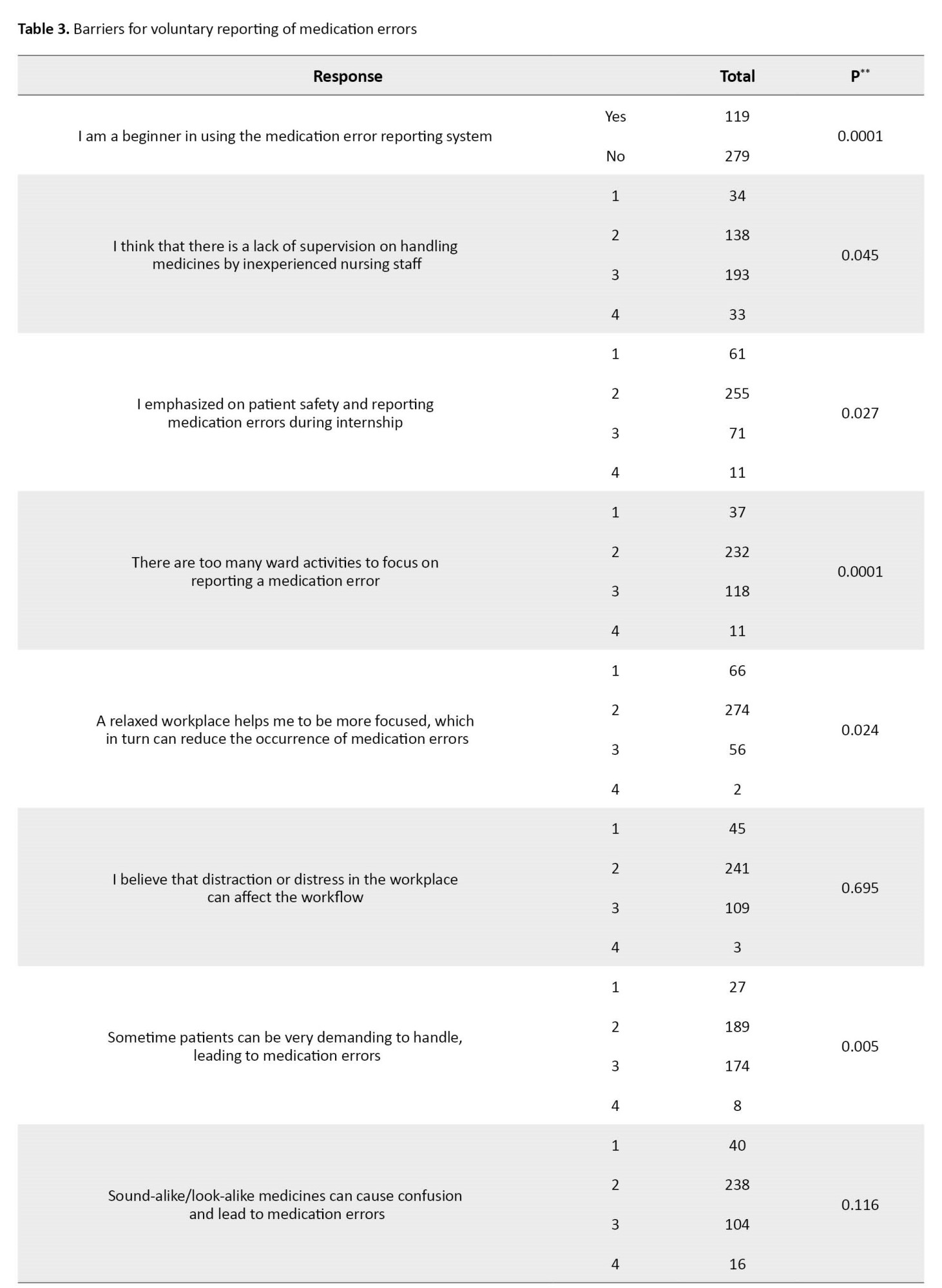

Based on Table 2 information, the results related to the barriers to voluntary ME reporting showed that 30% were novice in using the ME reporting; 67.9% reported that they had too many ward activities to focus on reporting; 54.3% reported that patients were too demanding to handle; 27.6% reported personnel problems, and 26.1% reported financial/economic problems.

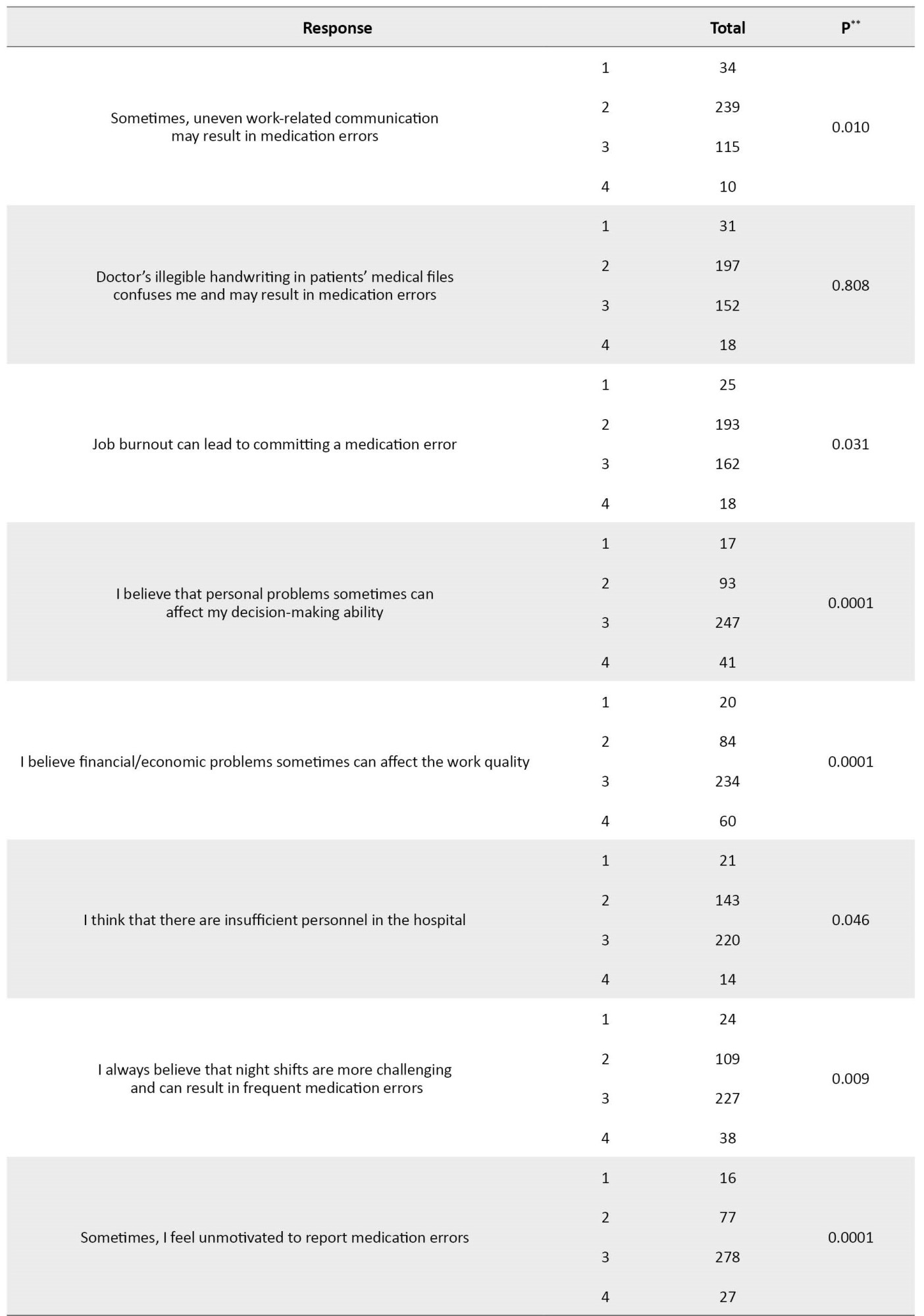

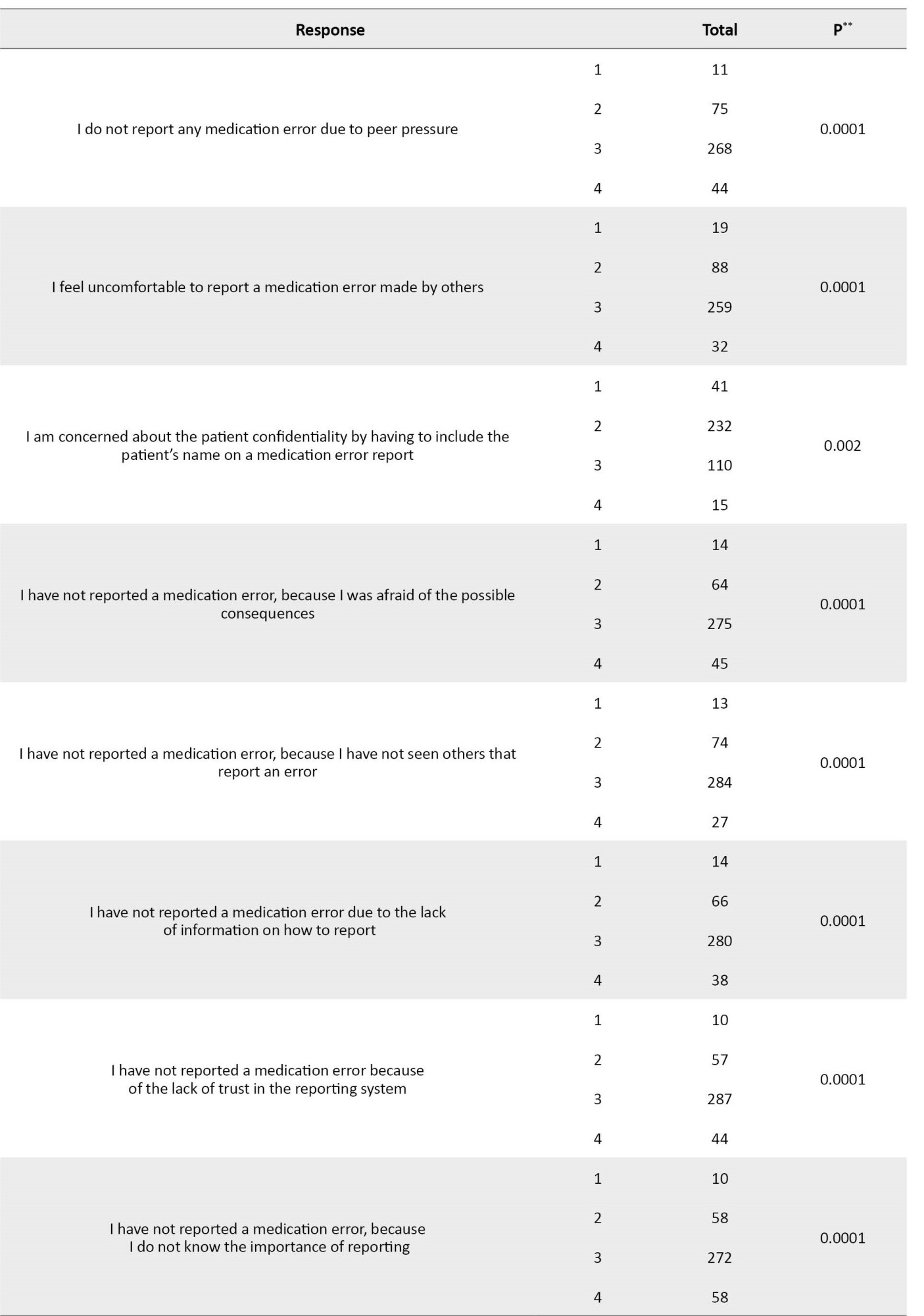

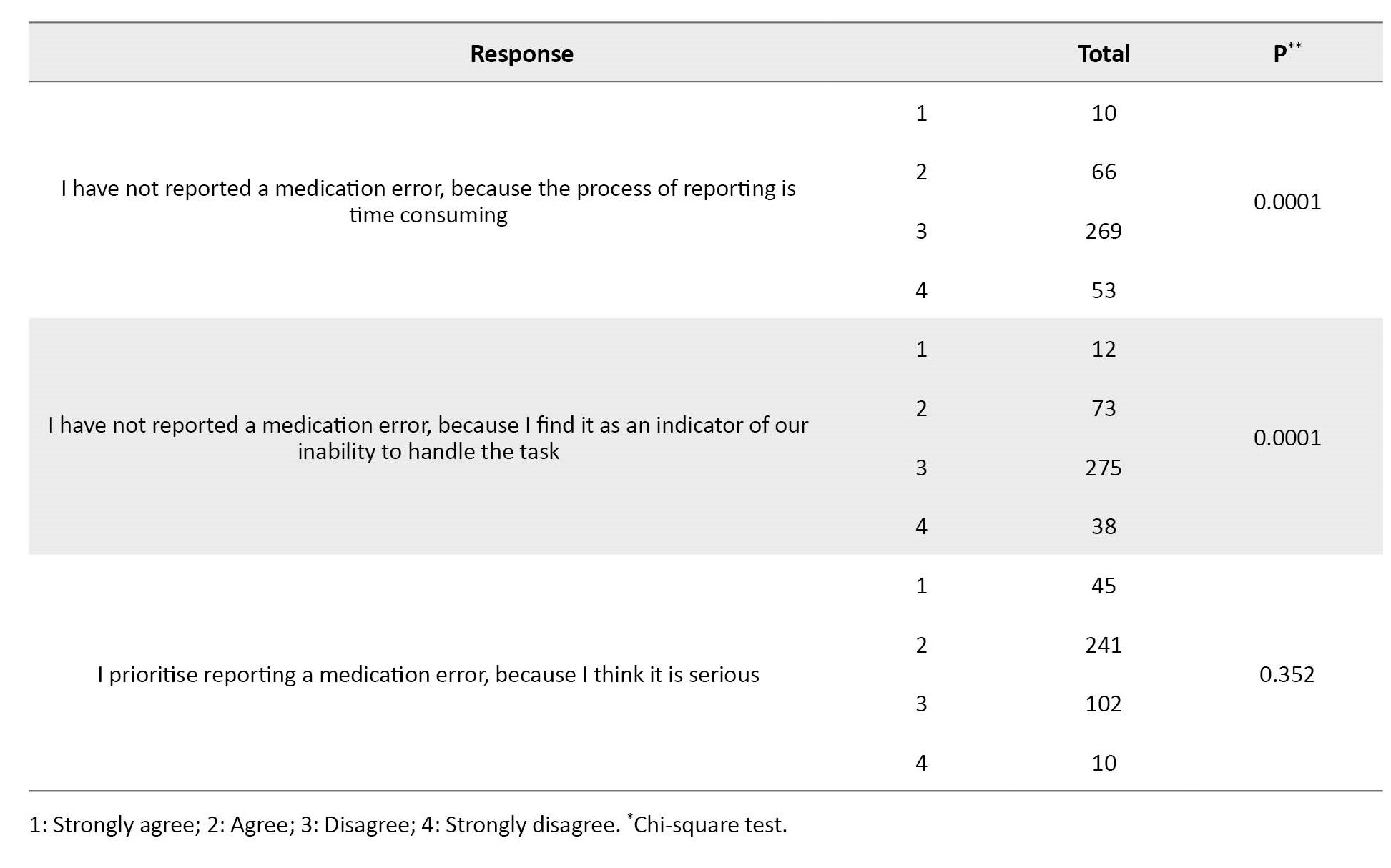

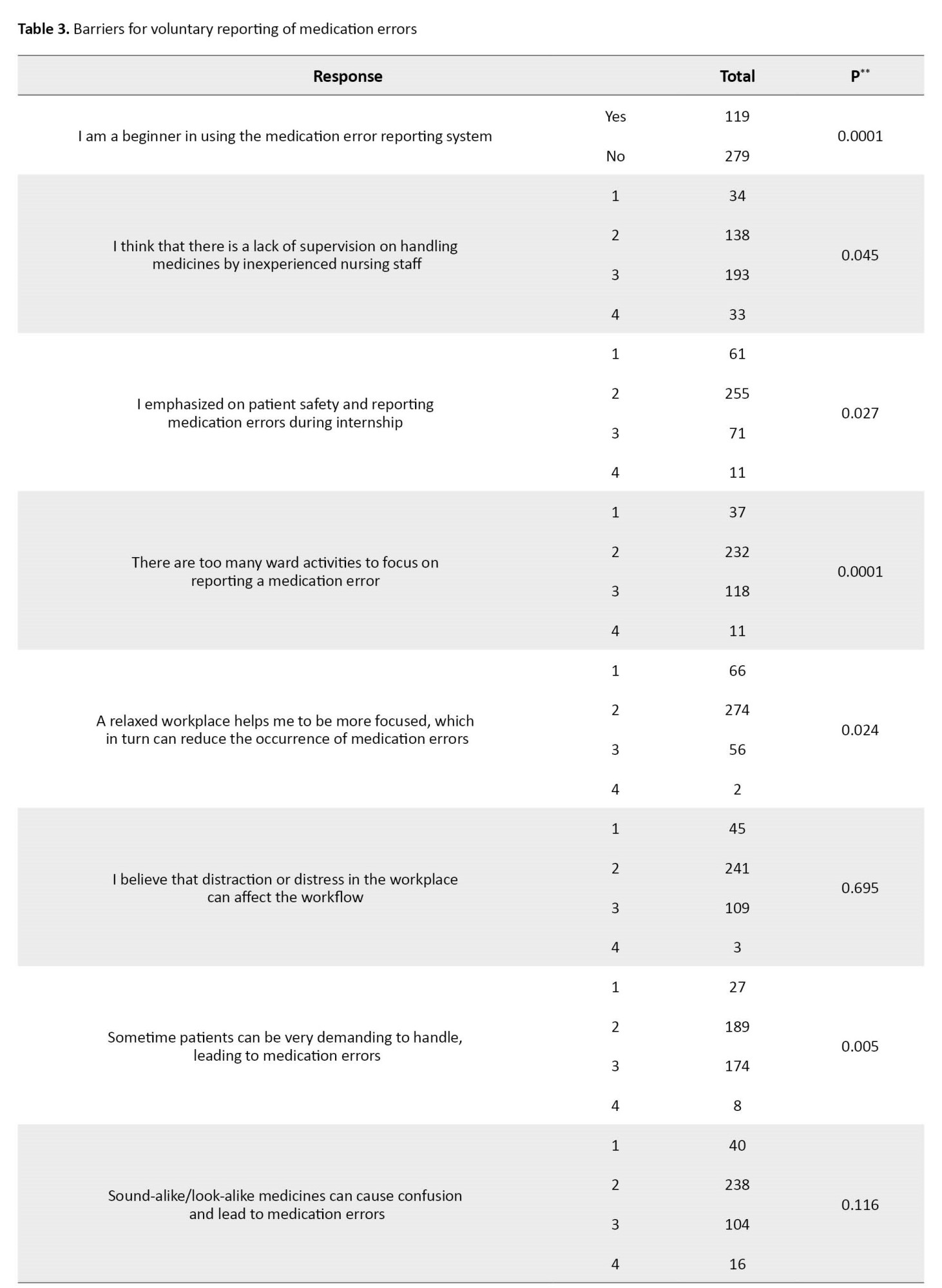

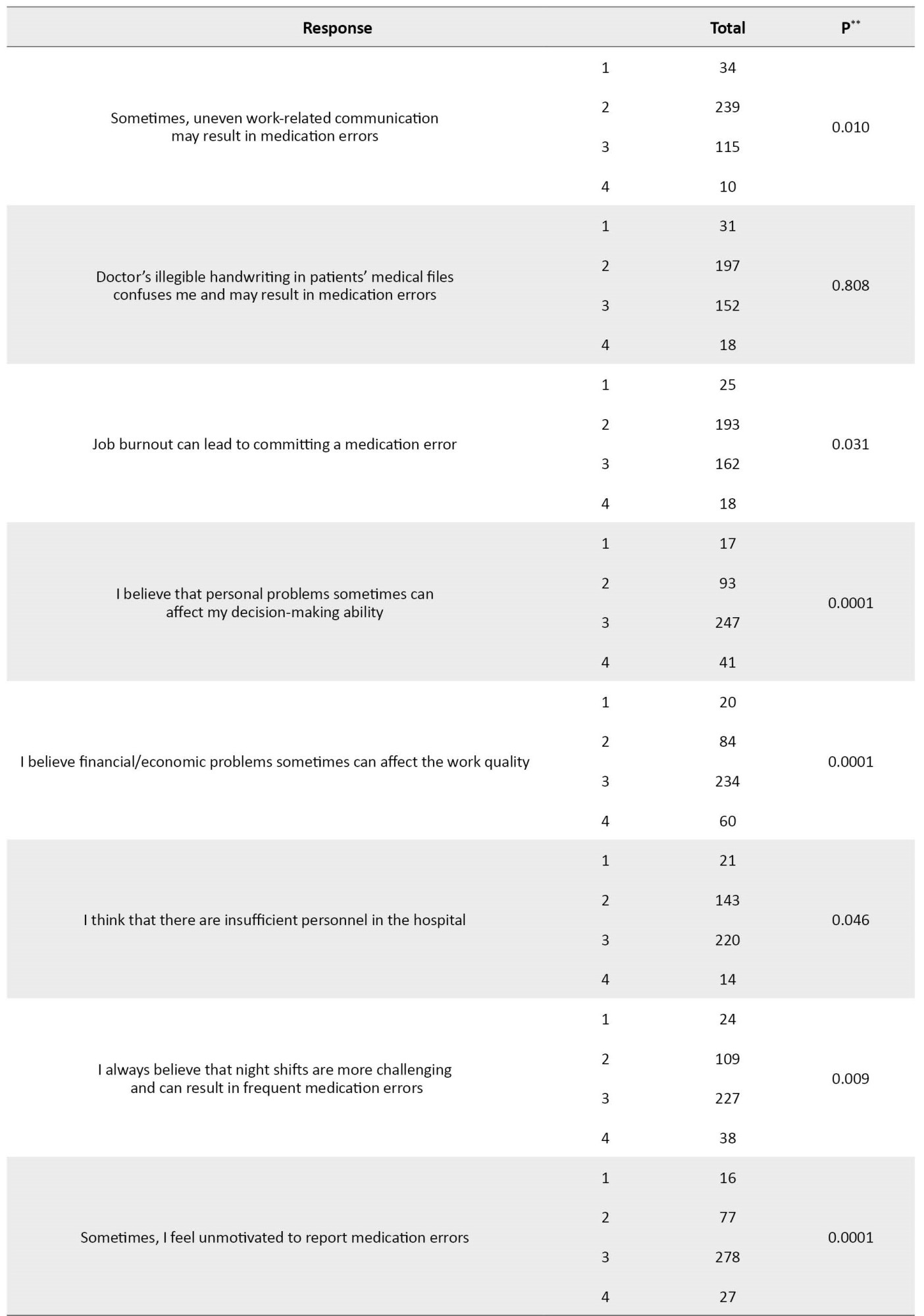

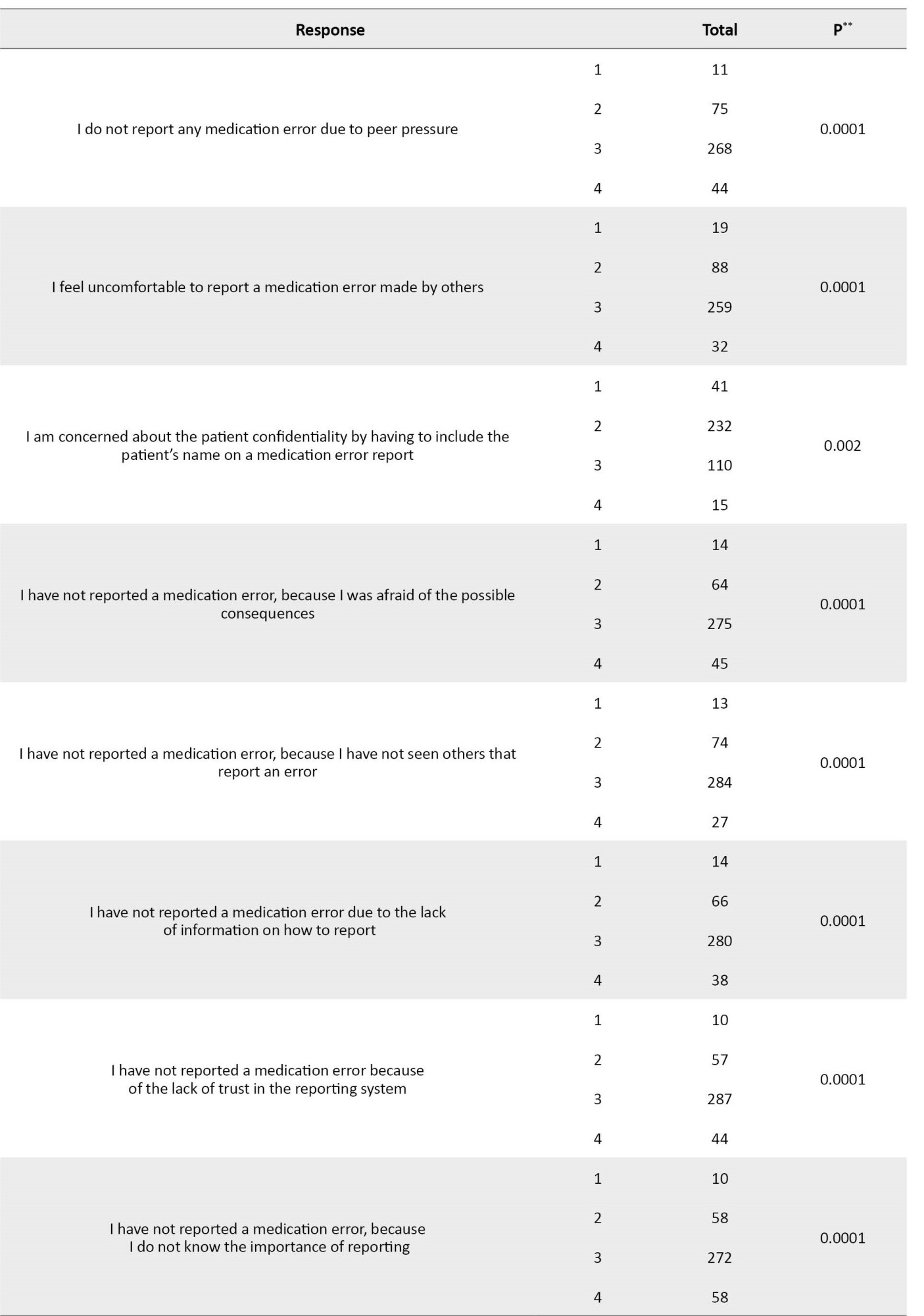

These were statistically significant (P<0.05). Other significant barriers to reporting MEs are reported in Table 3.

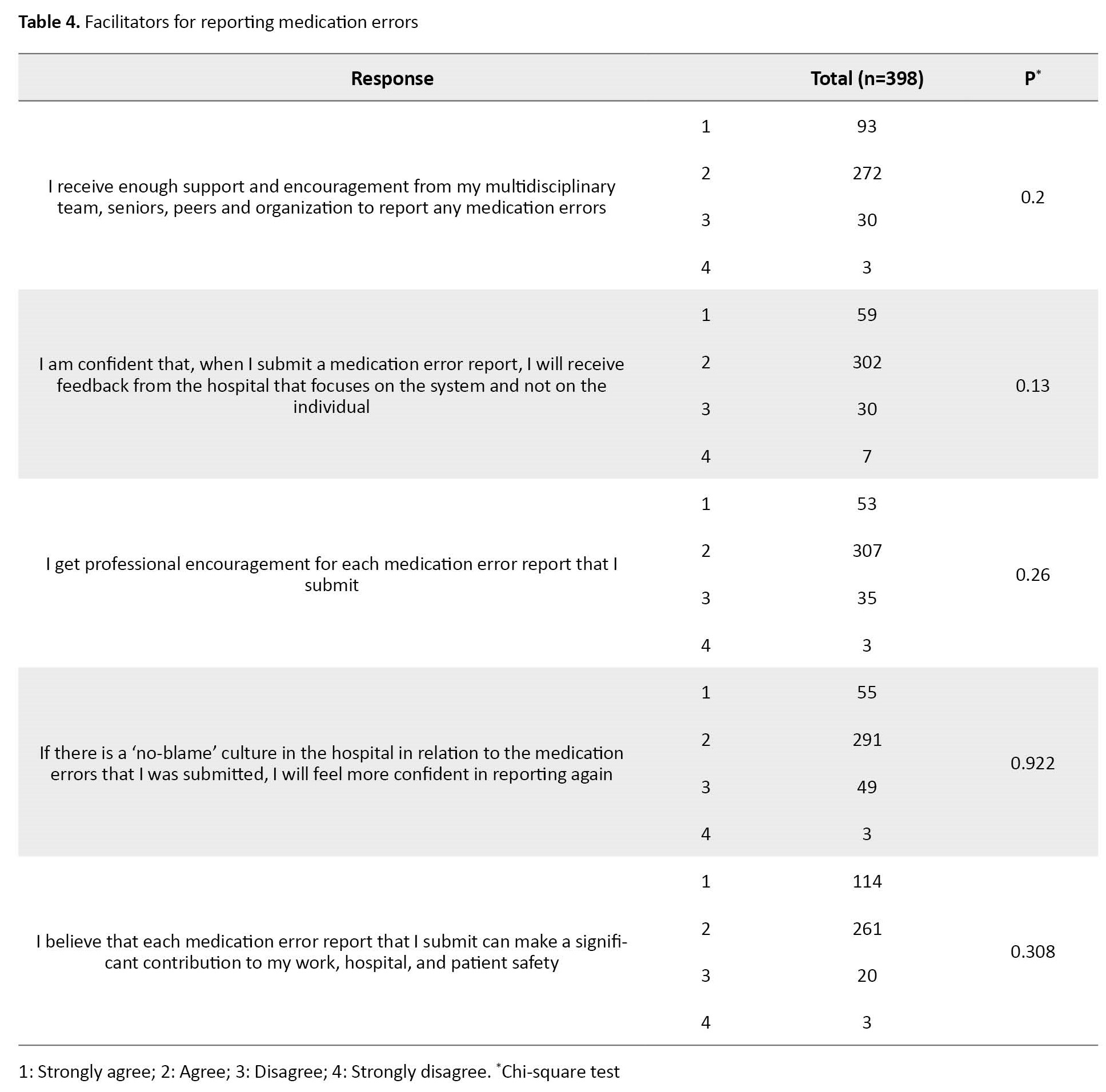

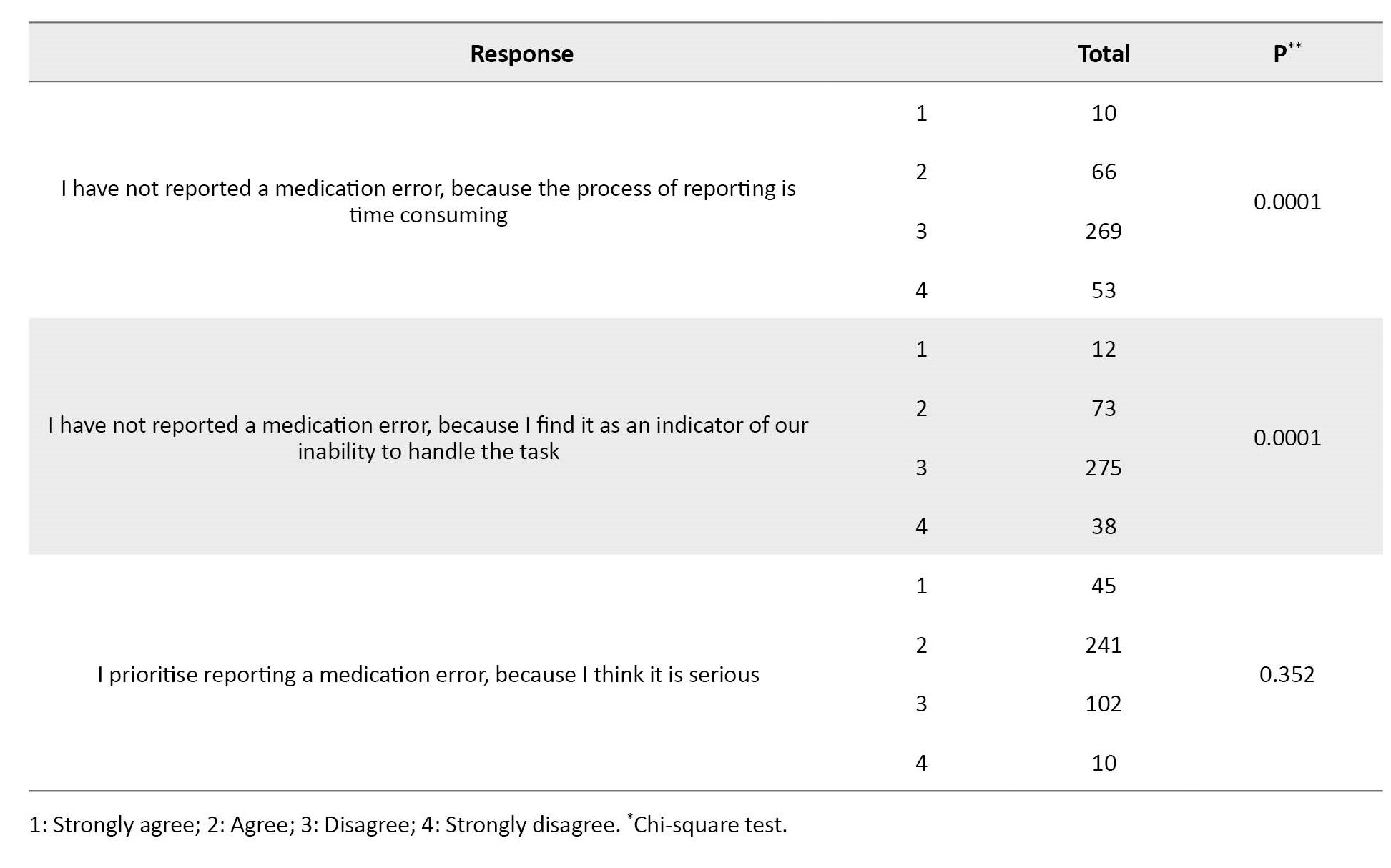

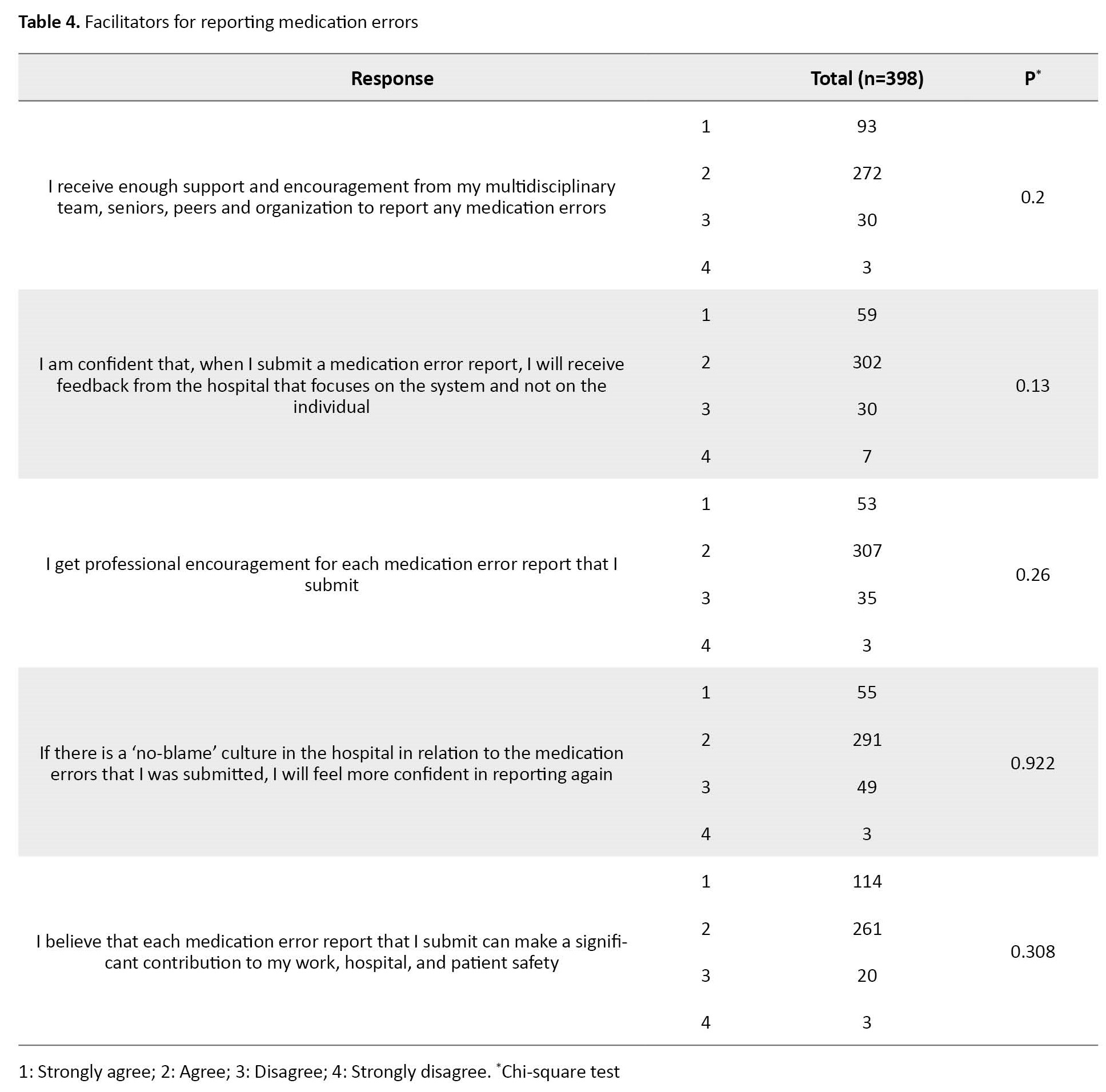

The results related to the facilitators of the voluntary ME reporting showed that professional encouragement (90.4%), receiving a feedback for the reported errors that focuses on the system and not on any individuals (90.7%), a “no-blame” culture (86.9%), the belief in the significant contribution of ME reporting to professional practice, organization, and patient safety (94.2%), and support and encouragement from the multi-disciplinary team (91.7%) were the facilitating; however, none of them were statistically significant (Table 4).

Discussion

The occurrence of MEs is a threat to patient safety. The goal of medication therapy is to achieve the best therapeutic outcome while enhancing the patient’s quality of life [12]. Well-qualified practical nurses can accept many roles for resolving patient care challenges and being an integral part of the healthcare team [13]. In the current study, the researchers aimed to investigate the different barriers and facilitators of voluntary ME reporting according to nurses in India. The majority of the nurses had 5-10 years of nursing experience. With increasing experience, nurses learn more about the various types of MEs and the factors contributed to these errors. With this experience, they can lower the chance of ME by being more vigilant and taking preventative measures.

Although low ME is considered a success for healthcare professionals, the gap between the ME occurrence and the voluntary ME reporting rate is an important indicator of patient safety. As a result, it is important to develop an effective ME reporting system to identify and reduce the contributing factors and barriers to reporting MEs [14]. Mirghafourvand et al. reported the various barriers and facilitators of ME reporting and emphasised the importance of the need to develop a ME reporting system [15].

The probability of reporting ME in the healthcare professionals may increase if most of them become aware of the importance of ME reporting. Healthcare professionals are more liable to report ME when they are aware of the potential benefits and advantages of ME reporting. Nurses are often hesitant to report mistakes/errors committed by a colleague at work. A variety of reasons play behind this hesitancy such as lack of knowledge about how to report, peer pressure, a lack of trust in the reporting system, potential consequences after reporting, and so on. Thus, removing these barriers to reporting MEs can encourage nursing staff to report their errors voluntarily, since the increase in the number of barriers, can reduce the ME reports [16].

The most significant barriers identified in the current study according to nurses were being a novice in using the ME reporting system, having too many ward activities to focus on, patients being too demanding to handle, personnel problems, financial/economic problems, having night shifts, lack of motivation, and peer pressure. In a study conducted by Travaglia et al., some of the above-mentioned barriers were also identified, such as the time-consuming process of ME reporting and job-related threats [17]. The likelihood of reporting ME can be reduced by the barriers such as fear of retaliation or worries about confidentiality. Healthcare professionals may choose not to report MEs that they notice or commit if they believe that it can affect handling the tasks assigned to them.

A number of facilitators are required for voluntary ME reporting process. Nurses in our study reported many facilitators. In a study conducted by Bakry, 62.6% of nursing staff reported a “no-blame” culture as the major facilitator of ME reporting [18]. To address and reduce the ME reporting barriers, facilitators need to be found. Healthcare professionals are more likely to feel confident and empowered to report MEs when organizations implement policies and procedures that support reporting of MEs.

ME are also a significant fear for patients. In a study conducted by Maxwell, it was reported that ME occurrence is a multi-factorial problem; when a ME occurs, healthcare professionals should look for all potential responsible factors [19]. In a study conducted by Dyab et al [20], various barriers to ME reporting in nursing practise were surveyed, and they suggested that identifying and resolving them is needed. Personnel neglect, unfamiliarity with the medication, insufficient training, heavy workload, new staff [21], low work experience [22], tiredness, exhaustion, burnout [23] illegible prescriptions, distractions/interruptions, and confusion between two similar drugs names [24] are some of the most prominent barriers to ME reporting.

There are few limitations in conducting this study. While maximum effort was taken to reduce the response bias, a neglected bias may exist in responses. Also, the duration of the study was short; the number of participants could be higher with an increase in the study period. The nurses’ works in three different shifts made it difficult to survey their responses.

The engagement of nursing staff in ME reduction and prevention is essential. As a result, there is a need to create an environment in which nurses feel free to report MEs without fear of repercussions and the regard for whether the occurred error was serious or not. It is also essential to design a reporting system by which nurses can feel secure and confident in reporting MEs and prevent future incidences of errors.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of JSS Medical College prior to the study (Code: JSSMC/IEC/17112021/37NCT/2021-22).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design, methodology, data collection, data analysis and drafting the manuscript: Ravina Ravi, Sri Harsha Chalasani, and Praveen Kulkarni; Review and editing: Sri Harsha Chalasani, Praveen Kulkarni, Madhan Ramesh, and Janet Mathias; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank Priya J Aradhya and Ascharya Chintalapati, and the manager of the JSS Hospital, the JSS College of Pharmacy, and the JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research for their guidance and support.

References

The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) has defined the medication error (ME) as “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing, order communication, product labelling, packaging and nomenclature, compounding, dispensing, distribution, administration, education, monitoring, and use” [1]. MEs have been estimated to cost 42 billion USD per year accounting for nearly 1% of total global health costs [2]. A study conducted in Australia found that 16.6% of all hospital admissions were associated with an avoidable adverse event, with nearly 5% of cases involving an iatrogenic injury leading to death. An 11% adverse event rate was reported by a retrospective study conducted in the United Kingdom (UK). Studies conducted in other countries have revealed comparable incidences of adverse events; one in New Zealand reported a rate of 10.7%, while another in Denmark reported a rate of 9% [3]. In a study conducted on hospitalized patients in Uttarakhand, India, the prevalence of MEs was reported to be 25.7% [4]. MEs can occur during prescribing, transcribing, dispensing, procurement, administration, and/or monitoring of a drug [5]. These errors can cause considerable negative outcomes, which not only affect the patients’ health but also cause unnecessary hospital re-admissions and prolongation of hospital stay. This drastically affects patient satisfaction and reduces their confidence in the healthcare system [6, 7].

Any member of the healthcare team can make MEs. Healthcare specialists in general and nurses in particular are responsible for reporting MEs. the MEs by nurses are most common, mainly because all prescribed medications are given by the nurses and they spend most of the time administering drugs to patients. Consequently, they should administer medications cautiously and prevent any incidence of medication errors [8, 9, 10, 11]. Thus, medication errors can hinder nursing care and cause a preventable harm to patients. Despite the rise in ME prevalence, most of them are often under-reported within the healthcare settings. The ME reporting should be a voluntary action to help reduce or prevent future mistakes that can cause patient damage. It can also reduce the associated financial and personal costs. Since ME reporting is an important patient safety criterion, identifying its facilitators and barriers is critical for patient safety investigation. This study aims to investigate the barriers and facilitators of voluntarily ME reporting among the nursing staff in India.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out for 6 months from May to October 2022. Out of 800 nurses, 511 nurses who were involved in ward round activities and were working in three work shifts from various specialities participated (286 nurses including interns, practical nurses, and nursing managers were excluded). Using a convenience sampling method, 398 nurses from among 511 nurses were included in the study (116 nurses did not enter in study as they did not respond to the questionnaire).

After a literature review, a questionnaire measuring the facilitators and barriers to reporting MEs was designed. It was a 39-items tool with four sections (demographic information, knowledge, barriers, and facilitators). The questionnaire was validated based on the opinions of 11 healthcare professionals (4 physicians, one chief nurse, and 6 charge nurses) by measuring the item-content validity index (I-CVI) and scale-content validity index (S-CVI). The overall I-CVI was 0.92. Since it was more than 80%, none of the items needed further change or removal. An average S-CVI score of 94.6% for Relevance, 93.2% for clarity, 94.2% for ambiguity, and 96.4% for simplicity were obtained. The Cronbach’s α value was obtained as 0.86, 0.88 and 0.87 for the knowledge, barriers, and facilitators subscales, respectively. The first section surveys the demographic characteristics of nurses (such as age, gender, working department, years of experience, and educational level). The second section consists of seven items measuring the knowledge of MEs and the reporting system; six items are answered by Yes (1 point) and No (0 points), and one item (assessing the number of MEs reported) is answered by “0 reports”, “1-5 reports”, and “more than 5 reports”. The third section with 27 items uses a Likert scale as 1=strongly agree, 2=agree, 3=disagree, 4=strongly disagree to surveys the barriers to voluntary reporting of MEs. The last section with 5 items rated on a Likert scale as 1=strongly agree, 2=agree, 3=disagree, 4=strongly disagree, surveys the facilitators of voluntary ME reporting

The questionnaire was prepared using the Google Form and the link was sent to the nursing staffs and their responses were collected. Chi-square test was used to determine if there is any significant difference among the nurse’s responses to each items of the subscales facilitators and barriers to determine their willingness to engage in voluntary ME reporting. All collected data were entered and analyzed in SPSS software, version 18. The variables such as age, gender, and educational level were described using the statistics of frequency and percentage.

Results

Of 511 nurses, 398 completed the questionnaires (response rate=77.9%), of whom 87% were female and 13% were male. The majority were at an age range of 31–40 years (44.9%). For more information, see Table 1.

The majority (85.67%) had a diploma, followed by 12.56% with a bachelor’s degree in nursing, and 1.75% with a master’s degree in nursing.

The results related to the knowledge of MEs, their impacts, and the reporting system showed that 96.2% had good knowledge, whereas 3.85% were unaware of the existence of a ME reporting system in the hospital and chi square test showed only ʹawareness of the existence of a medication error reporting system in the hospital was significant (P=0.004).

Based on Table 2 information, the results related to the barriers to voluntary ME reporting showed that 30% were novice in using the ME reporting; 67.9% reported that they had too many ward activities to focus on reporting; 54.3% reported that patients were too demanding to handle; 27.6% reported personnel problems, and 26.1% reported financial/economic problems.

These were statistically significant (P<0.05). Other significant barriers to reporting MEs are reported in Table 3.

The results related to the facilitators of the voluntary ME reporting showed that professional encouragement (90.4%), receiving a feedback for the reported errors that focuses on the system and not on any individuals (90.7%), a “no-blame” culture (86.9%), the belief in the significant contribution of ME reporting to professional practice, organization, and patient safety (94.2%), and support and encouragement from the multi-disciplinary team (91.7%) were the facilitating; however, none of them were statistically significant (Table 4).

Discussion

The occurrence of MEs is a threat to patient safety. The goal of medication therapy is to achieve the best therapeutic outcome while enhancing the patient’s quality of life [12]. Well-qualified practical nurses can accept many roles for resolving patient care challenges and being an integral part of the healthcare team [13]. In the current study, the researchers aimed to investigate the different barriers and facilitators of voluntary ME reporting according to nurses in India. The majority of the nurses had 5-10 years of nursing experience. With increasing experience, nurses learn more about the various types of MEs and the factors contributed to these errors. With this experience, they can lower the chance of ME by being more vigilant and taking preventative measures.

Although low ME is considered a success for healthcare professionals, the gap between the ME occurrence and the voluntary ME reporting rate is an important indicator of patient safety. As a result, it is important to develop an effective ME reporting system to identify and reduce the contributing factors and barriers to reporting MEs [14]. Mirghafourvand et al. reported the various barriers and facilitators of ME reporting and emphasised the importance of the need to develop a ME reporting system [15].

The probability of reporting ME in the healthcare professionals may increase if most of them become aware of the importance of ME reporting. Healthcare professionals are more liable to report ME when they are aware of the potential benefits and advantages of ME reporting. Nurses are often hesitant to report mistakes/errors committed by a colleague at work. A variety of reasons play behind this hesitancy such as lack of knowledge about how to report, peer pressure, a lack of trust in the reporting system, potential consequences after reporting, and so on. Thus, removing these barriers to reporting MEs can encourage nursing staff to report their errors voluntarily, since the increase in the number of barriers, can reduce the ME reports [16].

The most significant barriers identified in the current study according to nurses were being a novice in using the ME reporting system, having too many ward activities to focus on, patients being too demanding to handle, personnel problems, financial/economic problems, having night shifts, lack of motivation, and peer pressure. In a study conducted by Travaglia et al., some of the above-mentioned barriers were also identified, such as the time-consuming process of ME reporting and job-related threats [17]. The likelihood of reporting ME can be reduced by the barriers such as fear of retaliation or worries about confidentiality. Healthcare professionals may choose not to report MEs that they notice or commit if they believe that it can affect handling the tasks assigned to them.

A number of facilitators are required for voluntary ME reporting process. Nurses in our study reported many facilitators. In a study conducted by Bakry, 62.6% of nursing staff reported a “no-blame” culture as the major facilitator of ME reporting [18]. To address and reduce the ME reporting barriers, facilitators need to be found. Healthcare professionals are more likely to feel confident and empowered to report MEs when organizations implement policies and procedures that support reporting of MEs.

ME are also a significant fear for patients. In a study conducted by Maxwell, it was reported that ME occurrence is a multi-factorial problem; when a ME occurs, healthcare professionals should look for all potential responsible factors [19]. In a study conducted by Dyab et al [20], various barriers to ME reporting in nursing practise were surveyed, and they suggested that identifying and resolving them is needed. Personnel neglect, unfamiliarity with the medication, insufficient training, heavy workload, new staff [21], low work experience [22], tiredness, exhaustion, burnout [23] illegible prescriptions, distractions/interruptions, and confusion between two similar drugs names [24] are some of the most prominent barriers to ME reporting.

There are few limitations in conducting this study. While maximum effort was taken to reduce the response bias, a neglected bias may exist in responses. Also, the duration of the study was short; the number of participants could be higher with an increase in the study period. The nurses’ works in three different shifts made it difficult to survey their responses.

The engagement of nursing staff in ME reduction and prevention is essential. As a result, there is a need to create an environment in which nurses feel free to report MEs without fear of repercussions and the regard for whether the occurred error was serious or not. It is also essential to design a reporting system by which nurses can feel secure and confident in reporting MEs and prevent future incidences of errors.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of JSS Medical College prior to the study (Code: JSSMC/IEC/17112021/37NCT/2021-22).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design, methodology, data collection, data analysis and drafting the manuscript: Ravina Ravi, Sri Harsha Chalasani, and Praveen Kulkarni; Review and editing: Sri Harsha Chalasani, Praveen Kulkarni, Madhan Ramesh, and Janet Mathias; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank Priya J Aradhya and Ascharya Chintalapati, and the manager of the JSS Hospital, the JSS College of Pharmacy, and the JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research for their guidance and support.

References

- National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention About Medication Errors [Internet]. 2020 [Updated 2012 April 25]. Available: [Link]

- WHO. WHO launches global effort to halve medication-related errors in 5 years. WHO. Geneva: WHO; 2017. [Link]

- Carver N, Gupta V, Hipskind JE. Medical Errors.2023 May 7. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PMID]

- Patel N, Desai M, Shah S, Patel P, Gandhi A. A study of medication errors in a tertiary care hospital. Perspect Clin Res. 2016; 7(4):168-73. [DOI:10.4103%2F2229-3485.192039] [PMID]

- FDA. Working to reduce medication errors. Maryland: FDA; 2019. [Link]

- Mousavi-Roknabadi RS, Momennasab M, Groot G, Askarian M, Marjadi B. Medical error and under-reporting causes from the viewpoints of nursing managers: A qualitative study. Int J Prev Med. 2022; 13:103. [DOI:10.4103%2Fijpvm.IJPVM_500_20] [PMID]

- Alzoubi MM, Al-Mahasneh A, Al-Mugheed K, Al Barmawi M, Alsenany SA, Farghaly Abdelaliem SM. Medication administration error perceptions among critical care nurses: A cross-sectional, descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023; 16:1503-12.[DOI:10.2147/JMDH.S411840] [PMID]

- Stolic S, Ng L, Southern J, Sheridan G. Medication errors by nursing students on clinical practice: An integrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2022; 112:105325. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105325] [PMID]

- Afaya A, Konlan KD, Do HK. Improving patient safety through identifying barriers to reporting medication errors among nurses: An integrative review. 2021. [pre-print]. [DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-271752/v1]

- Samsiah A, Othman N, Jamshed S, Hassali MA. Knowledge, perceived barriers and facilitators of medication error reporting: A quantitative survey in Malaysian primary care clinics. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020; 42(4):1118-27. [DOI:10.1007/s11096-020-01041-0] [PMID]

- Alanko K, Nyholm L. Oops! Another medication error: A literature review of contributing factors and methods to prevent medication errors. Helsinki: Helsingin Ammattikorkeakoulu Stadia; 2007. [Link]

- Rodziewicz TL, Houseman B, Hipskind JE. Medical error reduction and prevention. 2023. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PMID]

- Stewart D, Thomas B, MacLure K, Wilbur K, Wilby K, Pallivalapila A, et al. Exploring facilitators and barriers to medication error reporting among healthcare professionals in Qatar using the theoretical domains framework: A mixed-methods approach. PloS One. 2018; 13(10):e0204987. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0204987] [PMID]

- Garcia CL, Abreu LC, Ramos JLS, Castro CFD, Smiderle FRN, Santos JAD, et al. Influence of burnout on patient safety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina. 2019; 55(9):553. [DOI:10.3390/medicina55090553] [PMID]

- Mirghafourvand M, Hajizadeh K, Kondori J, Kamalifard M, Bazaz Javid Z. Barriers to and facilitators of medication error reporting from the viewpoints of nurses and midwives working in gynecology wards of Tabriz Hospitals. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2021; 26(3):104-10. [DOI:10.1177/25160435211009023]

- Maurer MJ. Nurses’ perceptions of and experiences with medication errors. Toledo: The University of Toledo;2010. [Link]

- Travaglia JF, Westbrook MT, Braithwaite J. Implementation of a patient safety incident management system as viewed by doctors, nurses and allied health professionals. Health. 2009; 13(3):277-96. [DOI:10.1177/1363459308101804] [PMID]

- Bakry SA. Nurse Perceptions and experiences of medication administration errors at governmental hospital in Gaza Governates. [PhD dissertation]. 2020.

- Maxwell SR, Webb DJ. Improving medication safety: Focus on prescribers and systems. Lancet. 2019; 394(10195):283-5. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31526-0] [PMID]

- Dyab EA, Elkalmi RM, Bux SH, Jamshed SQ. Exploration of nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceived barriers towards medication error reporting in a tertiary health care facility: A qualitative approach. Pharmacy. 2018; 6(4):120. [DOI:10.3390/pharmacy6040120] [PMID]

- Worringer B, Genrich M, Müller A, Gündel H, Contributors Of The Seegen Consortium, Angerer P. Hospital medical and nursing managers’ perspective on the mental stressors of employees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(14):5041. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17145041] [PMID]

- Seki Y, Yamazaki Y. Effects of working conditions on intravenous medication errors in a Japanese hospital. J Nurs Manag. 2006; 14(2):128-39. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00597.x] [PMID]

- Aziz NG, Osman GA, Rasheed HA. Nurses’ experiences and perceptions of medication administration errors. Zanco J Med Sci. 2018; 22(2):217-26. [DOI:10.15218/zjms.2018.029]

- Petrova E. Nurses’ perceptions of medication errors in Malta. Nurs Stand. 2010; 24(33):41-8. [DOI:10.7748/ns2010.04.24.33.41.c7717] [PMID]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2022/12/21 | Accepted: 2023/06/25 | Published: 2024/01/1

Received: 2022/12/21 | Accepted: 2023/06/25 | Published: 2024/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |