Fri, Jan 30, 2026

Volume 33, Issue 4 (9-2023)

JHNM 2023, 33(4): 268-277 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sabzeei S, Masoumi S Z, Kazemi F, Refaei M, Haghighi M. The Effect of Couple-centered Counseling on Sexual Self-concept and Sexual Violence in Pregnant Women. JHNM 2023; 33 (4) :268-277

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2227-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2227-en.html

Saeideh Sabzeei1

, Seyedeh Zahra Masoumi *2

, Seyedeh Zahra Masoumi *2

, Farideh Kazemi3

, Farideh Kazemi3

, Mansoureh Refaei4

, Mansoureh Refaei4

, Mohammad Haghighi5

, Mohammad Haghighi5

, Seyedeh Zahra Masoumi *2

, Seyedeh Zahra Masoumi *2

, Farideh Kazemi3

, Farideh Kazemi3

, Mansoureh Refaei4

, Mansoureh Refaei4

, Mohammad Haghighi5

, Mohammad Haghighi5

1- MSc in Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

2- Professor, Mother and Child Care Research Center, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran. ,zahramid2001@gmail.com

3- Assistant Professor, Mother and Child Care Research Center, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

4- Associate Professor, Mother and Child Care Research Center, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

5- Professor, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

2- Professor, Mother and Child Care Research Center, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran. ,

3- Assistant Professor, Mother and Child Care Research Center, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

4- Associate Professor, Mother and Child Care Research Center, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

5- Professor, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 570 kb]

(430 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1013 Views)

Full-Text: (647 Views)

Introduction

Pregnancy is one of the most critical periods in a woman’s life that can create profound physical, psychological, and behavioral changes. These physical and psychological changes affect couples’ sexual and marital relationships [1]. Pregnancy imposes a great deal of mental and physical pressure on women and, if accompanied by other stressors such as violence, can adversely affect the fetus and mother [2]. Violence against women during pregnancy is increasing and has become an intangible social challenge [3].

Sexual violence during pregnancy negatively impacts pregnant women and fetuses and leads to irreparable consequences, imposing huge costs on the health care system [4]. Sexual violence can increase complications during pregnancy, including acute injuries, preterm rupture of membranes, inability in life, eating disorders, sleep disorders, stress disorders, depression, substance abuse, and suicide. It can also result in placental abruption, miscarriage, and preterm birth. For this reason, women better be screened for sexual violence during the trimesters of pregnancy and after delivery [5].

Evidence shows that pregnancy and subsequent transfer to parental roles can upset the couples’ balance and comfort and cause changes in their previous communication patterns. Buchanan et al. reported that most women and their husbands experience increasing conflict during pregnancy, which can be a prelude to violence [6]. A study in Iran estimated the prevalence of sexual violence during pregnancy in this country to be 25.3% [7]. In another study, the prevalence rates of sexual violence during pregnancy in the world and Iran were estimated to be 17% and 28%, respectively, 11% higher in Iran [8]. Analyses have shown that women who have experienced sexual violence have undergone negative sexual self-concept changes [9].

Sexual self-concept results from previous experiences reflected in a person’s current life and impacts their sexual orientations and behavior in the future. It has two measurable positive and negative aspects that can overwhelm each other [10]. Women with a positive sexual self-concept have greater motivation and excitement about sexual issues and experience more romantic sexual relations than those with a negative sexual self-concept [11].

It seems that a solution to raise awareness and provide the necessary information to adopt various strategies to prevent domestic violence and have a positive effect on sexual self-concept is couple counseling, which helps the family and mother to consciously try to solve this problem [12].

Poorheidari et al. found the level of exposure of infertile women to violence in the intervention group after the implementation of counseling intervention significantly reduced in all dimensions of violence [13]. In another study, Lund et al. found that counseling pregnant women by health and delivery care providers in learning about the sexual changes that occur during pregnancy can lead to a positive sexual self-concept [14].

Sexual counseling is a long process whereby couples gain the necessary information and knowledge about sexual issues and form their attitudes, beliefs, and values. It is a process that contributes to healthy sexual development, marital health, interpersonal relationships, emotions, intimacy, body image, and sexual roles [15]. Due to the regular visits of pregnant women for prenatal care during pregnancy, it is a golden time to educate and counsel couples about the negative effects of sexual violence and negative sexual self-concept during pregnancy. The present study aims to determine the effect of couple-centered counseling on the sexual violence and sexual self-concept of pregnant women.

Materials and Methods

Stata software, version 13 was used to determine the sample size. Using the results of the analysis of domestic violence in Tafreshi et al. [16] and considering a 50% loss, the sample size for each group was calculated to be 26 (alpha=0.050, power=0.90, m1=81.4, m2=127.73, SD1=34.27, SD2=46.82).

The inclusion criteria for women were as follows: Willingness to participate in the study, being married, living in Hamedan City, Iran, ability to speak in Persian, not being under the treatment of a counselor or psychiatrist, normal pregnancy with a gestational age of 20 to 28 weeks without the use of assisted reproductive technology, obtaining a score of 34 to 68 based on Sheikhan’s sexual violence [17] and a score of 0 to 64 based on Ziaei’s sexual self-concept [18] questionnaires. The inclusion criteria for men were as follows: Tendency to participate in the study, monogamy, living in Hamadan, being able to speak Persian, and not being under the treatment of a counselor or psychiatrist based on the pregnant women’s medical and obstetric records. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Absence in counseling sessions for more than one session, unwillingness to continue the study, and the occurrence of an unfortunate incident during the counseling sessions (fetal loss, death of pregnant mother, death of spouse, etc.).

The data collection tools were the demographic characteristics, Sheikhan’s sexual violence, and Ziaei’s sexual self-concept questionnaires. The demographic characteristics questionnaire contained 31 items, and the sexual violence questionnaire contained 17 items, designed based on a 5-point Likert scale: Never, seldom, sometimes, often, and always [17]. The sexual self-concept questionnaire contained 78 items and 18 dimensions and was normalized in Iran by Ziaei. The questions were rated from 0 (this statement comes true for me completely) up to 4 (this statement never comes true for me), and the dimensions were categorized into negative sexual self-concept, positive sexual self-concept, and situational sexual self-concept [18]. Considering the study objectives, the scores of negative sexual self-concept were evaluated. The dimensions of negative sexual self-concept are anxiety (minimum 0 and maximum 20), monitoring (minimum 0 and maximum 12), fear (minimum 0 and maximum 20), and depression (minimum 0 and maximum 12). The faculty members of the Reproductive Health Department of Hamadan School of Nursing and Midwifery confirmed the validity of the sexual violence questionnaire. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to examine the reliability of the sexual violence questionnaire and sexual self-concept questionnaire, which 30 pregnant women completed within two weeks. The ICC values obtained for the sexual violence questionnaire and the sexual self-concept questionnaire were 0.96 and 0.88, respectively.

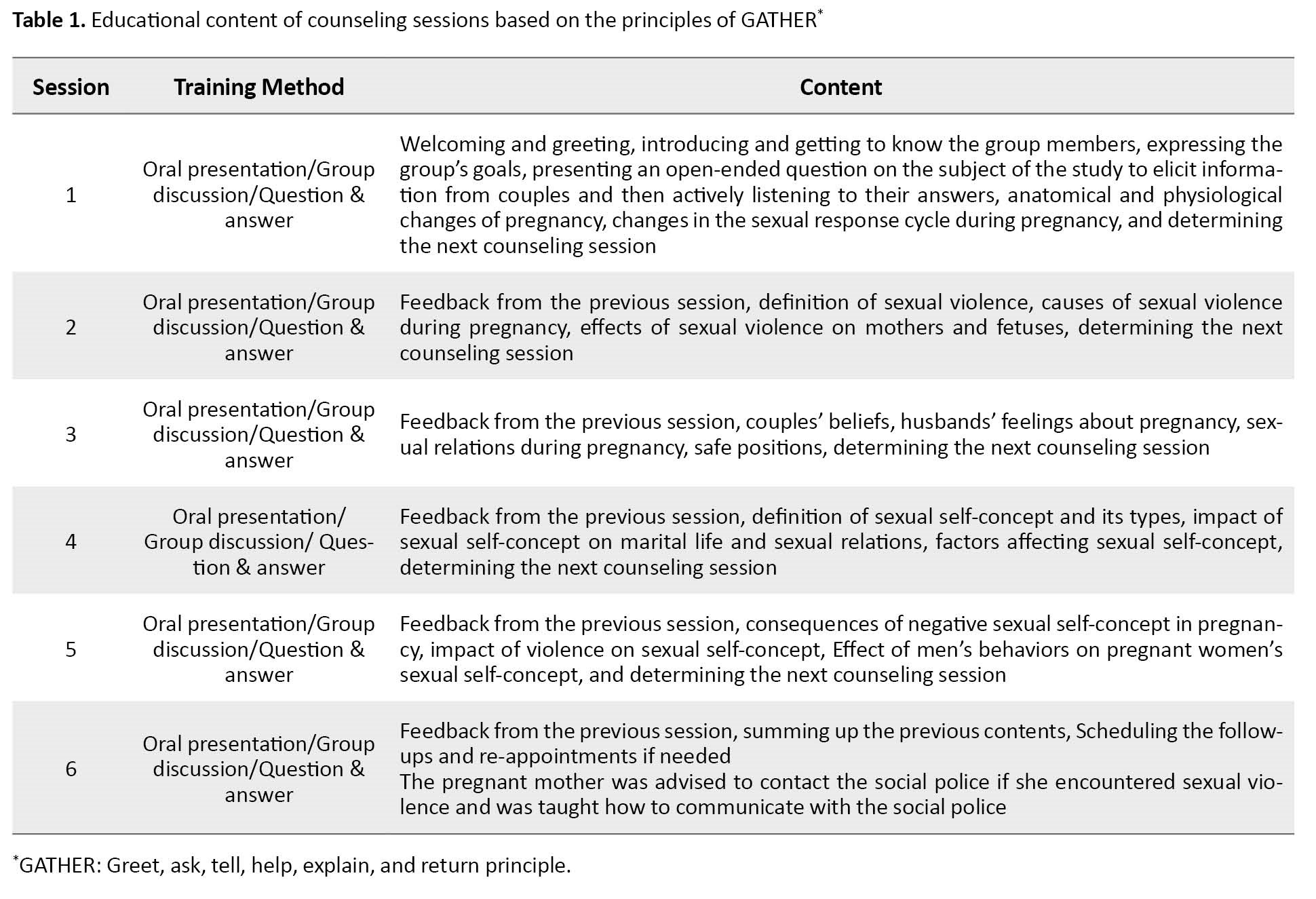

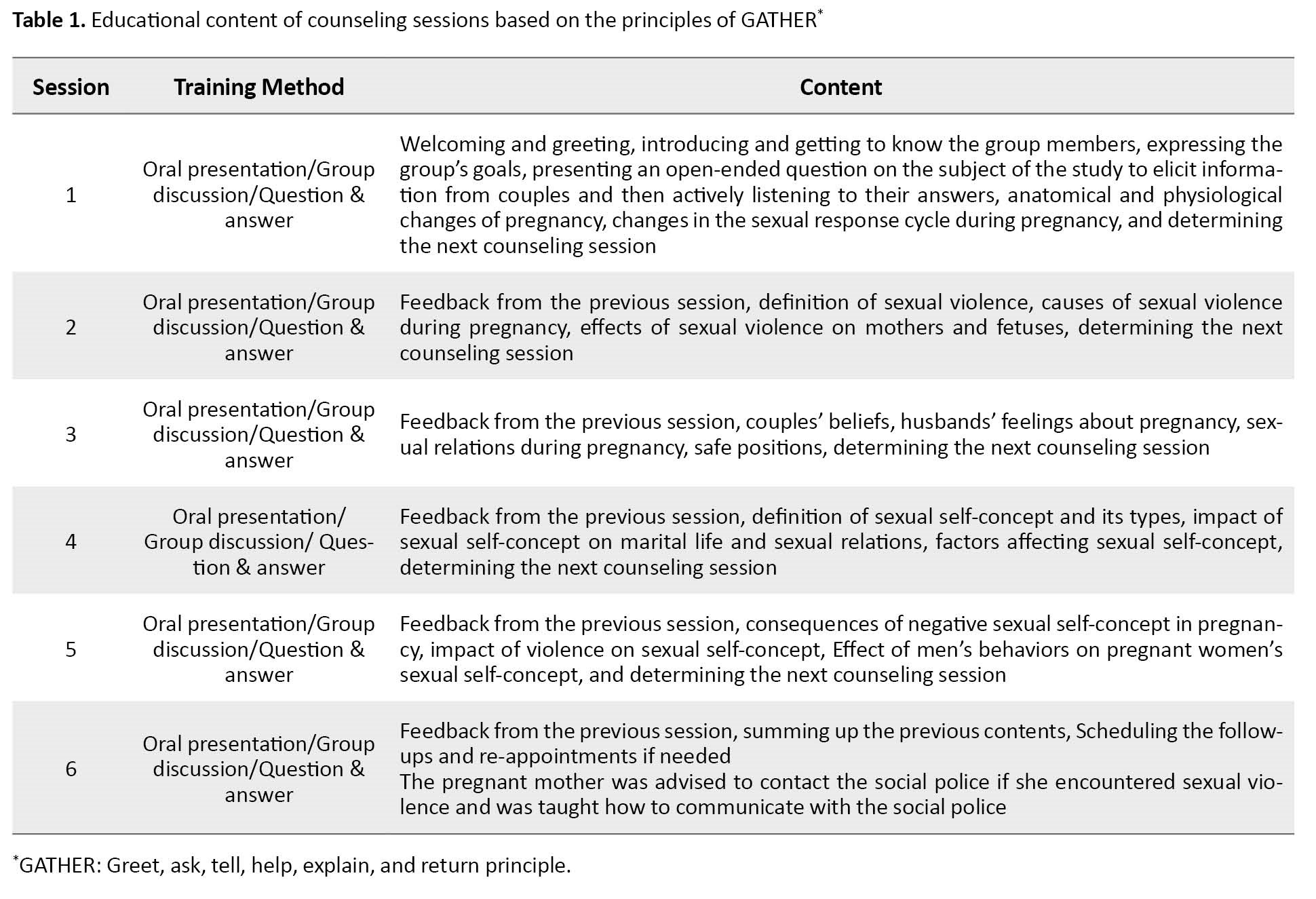

The interventional group received the intervention in 6 sessions with an interval of at least one week with couples being face to face. Each session lasting 60 minutes was held by the researcher based on counseling steps in GATHER (greet, ask, tell, help, explain, return) principles [19]. The sessions included 45 minutes of counseling and 15 minutes of questions and answers. Pregnant women and their husbands participated in these counseling sessions held in comprehensive health centers in Hamadan, and educational clips related to each topic were also used (Table 1).

The control group received only the routine care given during pregnancy. Due to the Coronavirus pandemic, meetings were held in compliance with health protocols. Four weeks after the sessions ended, two groups completed questionnaires again. To observe ethical issues, the control group members were given a training package containing the content of the sessions at the end of the research. All the data were obtained with the consent of the pregnant women in a completely private environment. The questionnaires were completed via the interview method, during which the pregnant women’s husbands were not allowed to be present.

The data were analyzed in Stata software, version 13. Intra-group comparisons were made using the paired t-test or Wilcoxon test, while the inter-group comparisons were made using the independent t-test or Mann-Withney U test.

Results

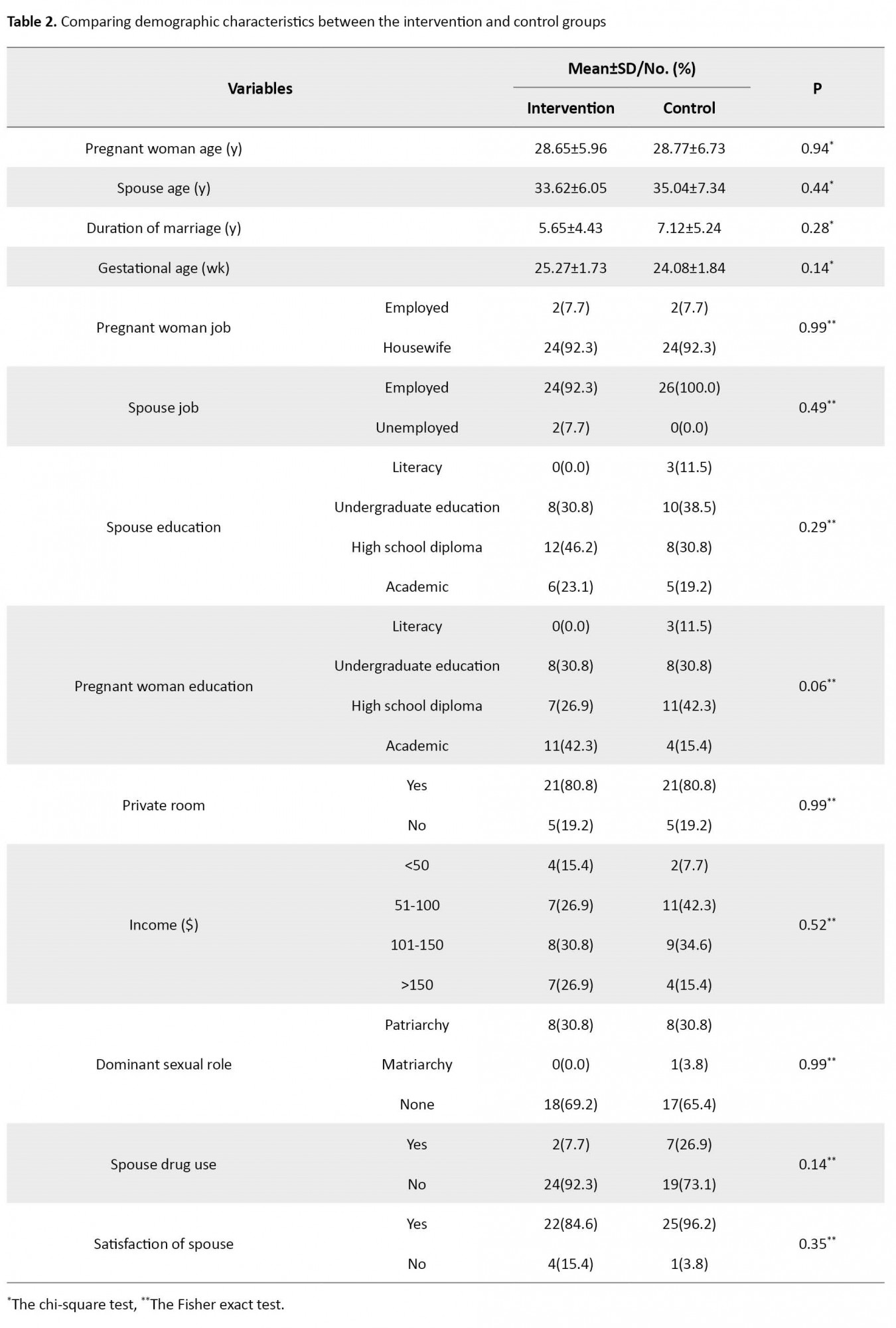

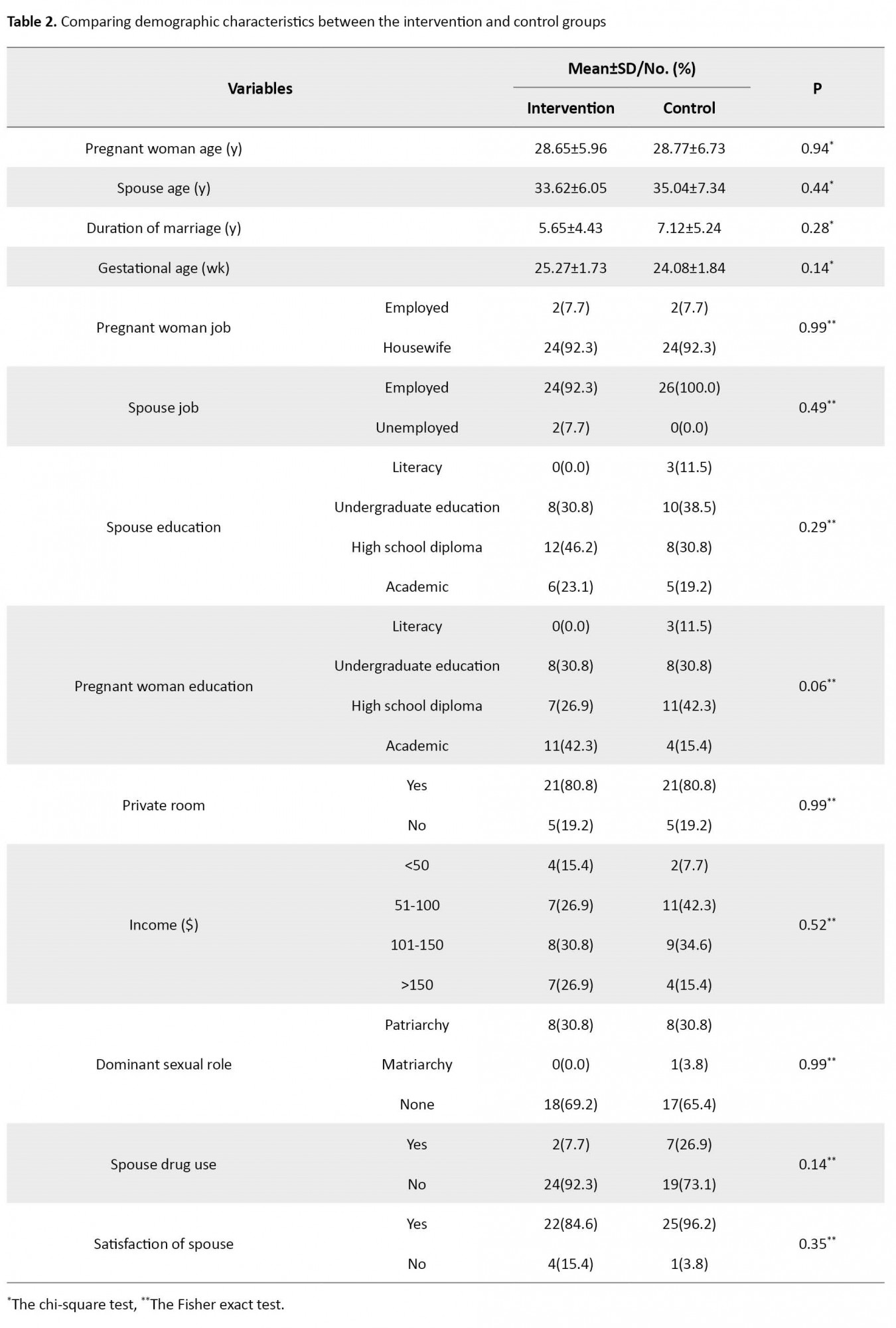

The Mean±SD age of pregnant women in the intervention group was 28.65±5.96, and in the control group was 28.77±6.73 years; the Mean±SD age of the spouses in the intervention group was 33.62±6.05 and in the control group was 35.04±7.34 years. The Mean±SD duration of marriage in the intervention group was 5.65±4.43 years, and in the control, it was 7.12±5.24 years; the mean gestational age in the intervention group was 25.27±1.73 and in the control group was 24.08±1.84 weeks. The majority of women in the intervention group (84.6%) and in the control group (96.2%) were satisfied with their spouses, but these differences were not statistically significant (Table 2).

The Mean±SD score of sexual violence in the intervention group changed from 34.65±0.93 to 25.92±2.20 after the intervention (P=0.001), and in the control group changed from 35.50±1.70 to 35.26±1.84, which showed no significant difference. Statistically, the difference between the mean score of sexual violence before the intervention was significant (P=0.03) between the two groups. The mean score of sexual violence after the intervention in the intervention group was lower than the control group, and there was a statistically significant difference (P=0.001).

The comparison of the mean scores of violence at the post-intervention stage demonstrated that by controlling the effect of scores before the intervention and gestational age, the mean score of violence in the intervention group was significantly (P=0.001) lower than that of the control group (Table 3).

After the intervention, all pregnant women in the intervention group reported no sexual violence, while in the control group, 24 women (92.3%) still reported mild violence.

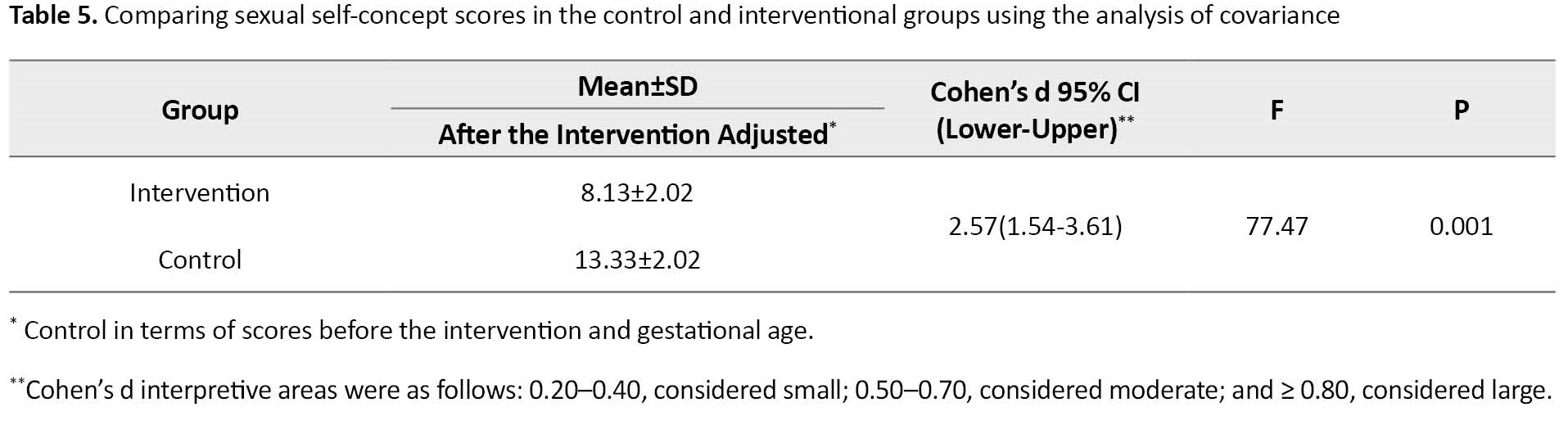

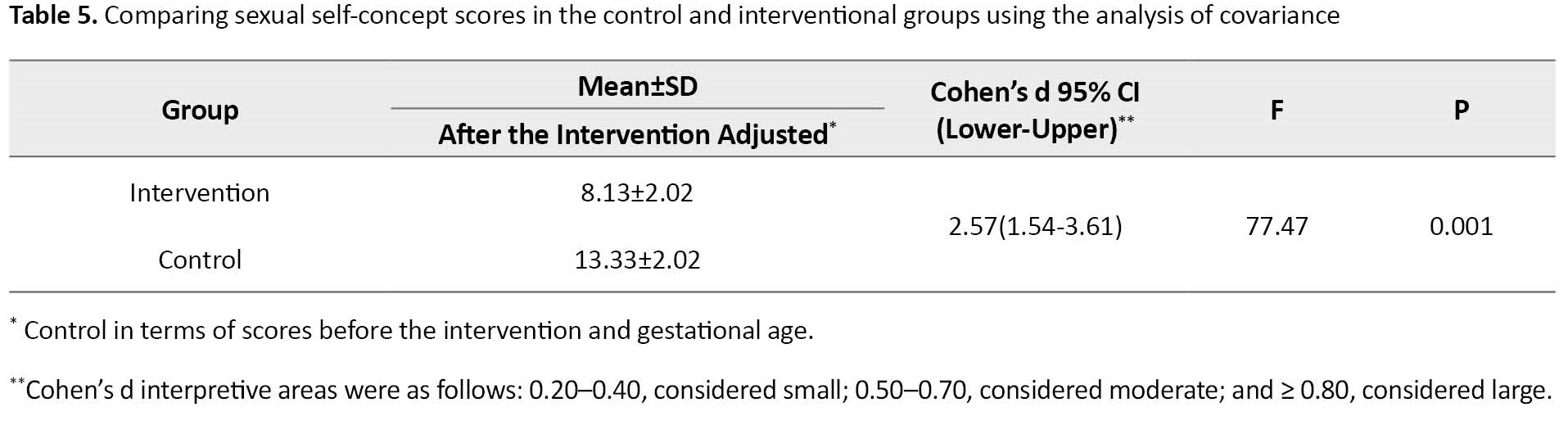

The Mean±SD score of sexual self-concept in the intervention group changed from 10.80±5.31 to 6.42±4.01 after the intervention (P=0.001), and in the control group changed from 14.69±9.01 to 15.03±8.61, showing no significant difference. Statistically, the difference between the mean score of sexual self-concept before the intervention between the two groups was not significant. The mean score of sexual self-concept after the intervention in the intervention group was lower than the control group and was statistically significant (P=0.001). In other words, the overall rate of negative sexual self-concept decreased after the intervention (Table 4).

The comparison of the mean scores of sexual self-concept at the post-intervention stage demonstrated that by controlling the effect of scores before the intervention and gestational age, the mean score of violence in the intervention group was significantly (P=0.001) lower than that of the control group (Table 5).

Comparing the mean scores showed a significant difference in negative sexual self-concept (fear, depression, monitoring, and anxiety) after the intervention between the two groups (P=0.001). So, the mean scores in the intervention group decreased after counseling. Also, in the intervention group, after counseling, the mean scores were reduced compared to pre-intervention (Table 6).

Discussion

The results of this study revealed that couple-centered counseling was effective in reducing sexual violence against pregnant women. The results of many studies have shown the high and beneficial effect of counseling on reducing sexual violence during pregnancy [20, 21, 22]. A study was conducted to determine the impact of life skills training on domestic violence reduction and general health scores. The educational intervention in the interventional group significantly reduced the participants’ mean general health score. Moreover, the mean number of general violence deeds and its dimensions, including verbal violence, hurting, and sexual violence, showed a statistically significant reduction [23]. Another study whose finding was consistent with the finding of the present study was the study performed to determine the effect of family-centered counseling on domestic violence in pregnant women. They found that family-centered intervention in the interventional group reduced the mean score of domestic violence. Various dimensions, including sexual violence, decreased significantly after the intervention [12].

In our study, the mean score of negative sexual self-concept in the intervention group decreased after counseling, indicating the intervention’s effectiveness.

Interventional studies using different psychological models about negative sexual self-concept have concluded that carrying out relevant consultations has affected increasing people’s awareness and attitude, as well as reducing negative sexual self-concept [24, 25, 26]. In our study, the score of all dimensions (anxiety, fear, monitoring, depression) of negative sexual self-concept decreased after the intervention, which means the intervention was effective. This finding was consistent with other studies [27, 28].

In the present study, raising couples’ awareness in applying the strategies presented in counseling sessions seems to have increased the husbands’ attention to providing comfort and reduced sexual violence against pregnant women as well as negative sexual self-concept. The couples’ increased awareness about sexual violence and sexual self-concept, and familiarity with the consequences of sexual violence, especially during pregnancy and its impact on pregnancy outcome, leads to their greater adjustment and ultimately reduces sexual violence and negative sexual self-concept.

The present study showed that couple-centered counseling, one of the easily accessible, low-cost, and safe methods, could reduce the severity of sexual violence and negative sexual self-concept among pregnant mothers. Couple-centered counseling is a supportive and solution-focused approach that aims to identify the problems, suggest an appropriate solution, and ultimately encourage people to change their cognition and behavior. It encompasses all the effective components of interpersonal relationships.

One of the strengths of our study is that contrary to intervention studies in which the educational and counseling content is not based on the needs assessment of couples, the focus is on education for women. The counseling sessions in the present study were based on individual and family characteristics and the couples’ living conditions and relationships. Pregnant women received counseling in the present study with their husbands—another strength of this study. One of the limitations of the present study is the differences in the participants’ literacy level and understanding of the content presented in counseling sessions, which could affect the proper implementation of strategies for them. However, we somewhat controlled the effect of this factor by increasing the number of counseling sessions. The low number of samples in this study due to the time limit in sampling is one of the study’s limitations, which reduces its generalizability to the whole society. Another limitation of the present study is that due to the Coronavirus conditions, the follow-up period of the participants in the study was 4 weeks, which is a short time.

According to the present study, couple-centered counseling effectively reduced sexual violence and negative sexual self-concept during pregnancy. Therefore, it is recommended as an effective, low-cost, and easily accessible health and medical care method. Given the importance of health care service providing centers in primary prevention, diagnosis, and management of cases of sexual violence and negative sexual self-concept in pregnant mothers, training counseling to health workers, especially midwives, will reduce the number of victims of this violence and provide a safe and effective environment to support and assist the victims of violence. It is recommended that midwives and other healthcare members in contact with mothers use this simple counseling method as part of perinatal care to step toward mother and baby health.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences approved the study (Code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1399.471). Written informed consent was taken from all participants in the study, and they were assured that their personal information would remain confidential. Also, exercise therapy was carried out for the control group after the study.

Funding

This project was funded by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, and administration: Saeideh Sabzee, Farideh Kazemi and Seyedeh Zahra Masoumi; Data collection: Saeideh Sabzee; Data analysis: Farideh Kazemi; Writing the manuscript: Mansoureh Refaei and Mohammad Haghighi; Review, editing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, esteemed professors, participants, and other people who helped us in this study are deeply appreciated.

References

Pregnancy is one of the most critical periods in a woman’s life that can create profound physical, psychological, and behavioral changes. These physical and psychological changes affect couples’ sexual and marital relationships [1]. Pregnancy imposes a great deal of mental and physical pressure on women and, if accompanied by other stressors such as violence, can adversely affect the fetus and mother [2]. Violence against women during pregnancy is increasing and has become an intangible social challenge [3].

Sexual violence during pregnancy negatively impacts pregnant women and fetuses and leads to irreparable consequences, imposing huge costs on the health care system [4]. Sexual violence can increase complications during pregnancy, including acute injuries, preterm rupture of membranes, inability in life, eating disorders, sleep disorders, stress disorders, depression, substance abuse, and suicide. It can also result in placental abruption, miscarriage, and preterm birth. For this reason, women better be screened for sexual violence during the trimesters of pregnancy and after delivery [5].

Evidence shows that pregnancy and subsequent transfer to parental roles can upset the couples’ balance and comfort and cause changes in their previous communication patterns. Buchanan et al. reported that most women and their husbands experience increasing conflict during pregnancy, which can be a prelude to violence [6]. A study in Iran estimated the prevalence of sexual violence during pregnancy in this country to be 25.3% [7]. In another study, the prevalence rates of sexual violence during pregnancy in the world and Iran were estimated to be 17% and 28%, respectively, 11% higher in Iran [8]. Analyses have shown that women who have experienced sexual violence have undergone negative sexual self-concept changes [9].

Sexual self-concept results from previous experiences reflected in a person’s current life and impacts their sexual orientations and behavior in the future. It has two measurable positive and negative aspects that can overwhelm each other [10]. Women with a positive sexual self-concept have greater motivation and excitement about sexual issues and experience more romantic sexual relations than those with a negative sexual self-concept [11].

It seems that a solution to raise awareness and provide the necessary information to adopt various strategies to prevent domestic violence and have a positive effect on sexual self-concept is couple counseling, which helps the family and mother to consciously try to solve this problem [12].

Poorheidari et al. found the level of exposure of infertile women to violence in the intervention group after the implementation of counseling intervention significantly reduced in all dimensions of violence [13]. In another study, Lund et al. found that counseling pregnant women by health and delivery care providers in learning about the sexual changes that occur during pregnancy can lead to a positive sexual self-concept [14].

Sexual counseling is a long process whereby couples gain the necessary information and knowledge about sexual issues and form their attitudes, beliefs, and values. It is a process that contributes to healthy sexual development, marital health, interpersonal relationships, emotions, intimacy, body image, and sexual roles [15]. Due to the regular visits of pregnant women for prenatal care during pregnancy, it is a golden time to educate and counsel couples about the negative effects of sexual violence and negative sexual self-concept during pregnancy. The present study aims to determine the effect of couple-centered counseling on the sexual violence and sexual self-concept of pregnant women.

Materials and Methods

This randomized controlled trial study was conducted on two groups to investigate the effect of couple-centered counseling on sexual self-concept and violence in pregnant women. The study was conducted on 52 pregnant women (26 people in each group) from August 2020 to February 2021 who had been referred to the comprehensive health centers of Hamadan, Iran, for prenatal care and met the inclusion criteria. They were selected using convenience sampling and provided informed consent for participation. Then, they were assigned to the control and intervention groups based on a predetermined allocation sequence. The allocation sequence was determined using blocks of size 4 before the study, based on which the type of intervention was written inside closed opaque packets and coded in sequence order (Figure 1).

Stata software, version 13 was used to determine the sample size. Using the results of the analysis of domestic violence in Tafreshi et al. [16] and considering a 50% loss, the sample size for each group was calculated to be 26 (alpha=0.050, power=0.90, m1=81.4, m2=127.73, SD1=34.27, SD2=46.82).

The inclusion criteria for women were as follows: Willingness to participate in the study, being married, living in Hamedan City, Iran, ability to speak in Persian, not being under the treatment of a counselor or psychiatrist, normal pregnancy with a gestational age of 20 to 28 weeks without the use of assisted reproductive technology, obtaining a score of 34 to 68 based on Sheikhan’s sexual violence [17] and a score of 0 to 64 based on Ziaei’s sexual self-concept [18] questionnaires. The inclusion criteria for men were as follows: Tendency to participate in the study, monogamy, living in Hamadan, being able to speak Persian, and not being under the treatment of a counselor or psychiatrist based on the pregnant women’s medical and obstetric records. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Absence in counseling sessions for more than one session, unwillingness to continue the study, and the occurrence of an unfortunate incident during the counseling sessions (fetal loss, death of pregnant mother, death of spouse, etc.).

The data collection tools were the demographic characteristics, Sheikhan’s sexual violence, and Ziaei’s sexual self-concept questionnaires. The demographic characteristics questionnaire contained 31 items, and the sexual violence questionnaire contained 17 items, designed based on a 5-point Likert scale: Never, seldom, sometimes, often, and always [17]. The sexual self-concept questionnaire contained 78 items and 18 dimensions and was normalized in Iran by Ziaei. The questions were rated from 0 (this statement comes true for me completely) up to 4 (this statement never comes true for me), and the dimensions were categorized into negative sexual self-concept, positive sexual self-concept, and situational sexual self-concept [18]. Considering the study objectives, the scores of negative sexual self-concept were evaluated. The dimensions of negative sexual self-concept are anxiety (minimum 0 and maximum 20), monitoring (minimum 0 and maximum 12), fear (minimum 0 and maximum 20), and depression (minimum 0 and maximum 12). The faculty members of the Reproductive Health Department of Hamadan School of Nursing and Midwifery confirmed the validity of the sexual violence questionnaire. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to examine the reliability of the sexual violence questionnaire and sexual self-concept questionnaire, which 30 pregnant women completed within two weeks. The ICC values obtained for the sexual violence questionnaire and the sexual self-concept questionnaire were 0.96 and 0.88, respectively.

The interventional group received the intervention in 6 sessions with an interval of at least one week with couples being face to face. Each session lasting 60 minutes was held by the researcher based on counseling steps in GATHER (greet, ask, tell, help, explain, return) principles [19]. The sessions included 45 minutes of counseling and 15 minutes of questions and answers. Pregnant women and their husbands participated in these counseling sessions held in comprehensive health centers in Hamadan, and educational clips related to each topic were also used (Table 1).

The control group received only the routine care given during pregnancy. Due to the Coronavirus pandemic, meetings were held in compliance with health protocols. Four weeks after the sessions ended, two groups completed questionnaires again. To observe ethical issues, the control group members were given a training package containing the content of the sessions at the end of the research. All the data were obtained with the consent of the pregnant women in a completely private environment. The questionnaires were completed via the interview method, during which the pregnant women’s husbands were not allowed to be present.

The data were analyzed in Stata software, version 13. Intra-group comparisons were made using the paired t-test or Wilcoxon test, while the inter-group comparisons were made using the independent t-test or Mann-Withney U test.

Results

The Mean±SD age of pregnant women in the intervention group was 28.65±5.96, and in the control group was 28.77±6.73 years; the Mean±SD age of the spouses in the intervention group was 33.62±6.05 and in the control group was 35.04±7.34 years. The Mean±SD duration of marriage in the intervention group was 5.65±4.43 years, and in the control, it was 7.12±5.24 years; the mean gestational age in the intervention group was 25.27±1.73 and in the control group was 24.08±1.84 weeks. The majority of women in the intervention group (84.6%) and in the control group (96.2%) were satisfied with their spouses, but these differences were not statistically significant (Table 2).

The Mean±SD score of sexual violence in the intervention group changed from 34.65±0.93 to 25.92±2.20 after the intervention (P=0.001), and in the control group changed from 35.50±1.70 to 35.26±1.84, which showed no significant difference. Statistically, the difference between the mean score of sexual violence before the intervention was significant (P=0.03) between the two groups. The mean score of sexual violence after the intervention in the intervention group was lower than the control group, and there was a statistically significant difference (P=0.001).

The comparison of the mean scores of violence at the post-intervention stage demonstrated that by controlling the effect of scores before the intervention and gestational age, the mean score of violence in the intervention group was significantly (P=0.001) lower than that of the control group (Table 3).

After the intervention, all pregnant women in the intervention group reported no sexual violence, while in the control group, 24 women (92.3%) still reported mild violence.

The Mean±SD score of sexual self-concept in the intervention group changed from 10.80±5.31 to 6.42±4.01 after the intervention (P=0.001), and in the control group changed from 14.69±9.01 to 15.03±8.61, showing no significant difference. Statistically, the difference between the mean score of sexual self-concept before the intervention between the two groups was not significant. The mean score of sexual self-concept after the intervention in the intervention group was lower than the control group and was statistically significant (P=0.001). In other words, the overall rate of negative sexual self-concept decreased after the intervention (Table 4).

The comparison of the mean scores of sexual self-concept at the post-intervention stage demonstrated that by controlling the effect of scores before the intervention and gestational age, the mean score of violence in the intervention group was significantly (P=0.001) lower than that of the control group (Table 5).

Comparing the mean scores showed a significant difference in negative sexual self-concept (fear, depression, monitoring, and anxiety) after the intervention between the two groups (P=0.001). So, the mean scores in the intervention group decreased after counseling. Also, in the intervention group, after counseling, the mean scores were reduced compared to pre-intervention (Table 6).

Discussion

The results of this study revealed that couple-centered counseling was effective in reducing sexual violence against pregnant women. The results of many studies have shown the high and beneficial effect of counseling on reducing sexual violence during pregnancy [20, 21, 22]. A study was conducted to determine the impact of life skills training on domestic violence reduction and general health scores. The educational intervention in the interventional group significantly reduced the participants’ mean general health score. Moreover, the mean number of general violence deeds and its dimensions, including verbal violence, hurting, and sexual violence, showed a statistically significant reduction [23]. Another study whose finding was consistent with the finding of the present study was the study performed to determine the effect of family-centered counseling on domestic violence in pregnant women. They found that family-centered intervention in the interventional group reduced the mean score of domestic violence. Various dimensions, including sexual violence, decreased significantly after the intervention [12].

In our study, the mean score of negative sexual self-concept in the intervention group decreased after counseling, indicating the intervention’s effectiveness.

Interventional studies using different psychological models about negative sexual self-concept have concluded that carrying out relevant consultations has affected increasing people’s awareness and attitude, as well as reducing negative sexual self-concept [24, 25, 26]. In our study, the score of all dimensions (anxiety, fear, monitoring, depression) of negative sexual self-concept decreased after the intervention, which means the intervention was effective. This finding was consistent with other studies [27, 28].

In the present study, raising couples’ awareness in applying the strategies presented in counseling sessions seems to have increased the husbands’ attention to providing comfort and reduced sexual violence against pregnant women as well as negative sexual self-concept. The couples’ increased awareness about sexual violence and sexual self-concept, and familiarity with the consequences of sexual violence, especially during pregnancy and its impact on pregnancy outcome, leads to their greater adjustment and ultimately reduces sexual violence and negative sexual self-concept.

The present study showed that couple-centered counseling, one of the easily accessible, low-cost, and safe methods, could reduce the severity of sexual violence and negative sexual self-concept among pregnant mothers. Couple-centered counseling is a supportive and solution-focused approach that aims to identify the problems, suggest an appropriate solution, and ultimately encourage people to change their cognition and behavior. It encompasses all the effective components of interpersonal relationships.

One of the strengths of our study is that contrary to intervention studies in which the educational and counseling content is not based on the needs assessment of couples, the focus is on education for women. The counseling sessions in the present study were based on individual and family characteristics and the couples’ living conditions and relationships. Pregnant women received counseling in the present study with their husbands—another strength of this study. One of the limitations of the present study is the differences in the participants’ literacy level and understanding of the content presented in counseling sessions, which could affect the proper implementation of strategies for them. However, we somewhat controlled the effect of this factor by increasing the number of counseling sessions. The low number of samples in this study due to the time limit in sampling is one of the study’s limitations, which reduces its generalizability to the whole society. Another limitation of the present study is that due to the Coronavirus conditions, the follow-up period of the participants in the study was 4 weeks, which is a short time.

According to the present study, couple-centered counseling effectively reduced sexual violence and negative sexual self-concept during pregnancy. Therefore, it is recommended as an effective, low-cost, and easily accessible health and medical care method. Given the importance of health care service providing centers in primary prevention, diagnosis, and management of cases of sexual violence and negative sexual self-concept in pregnant mothers, training counseling to health workers, especially midwives, will reduce the number of victims of this violence and provide a safe and effective environment to support and assist the victims of violence. It is recommended that midwives and other healthcare members in contact with mothers use this simple counseling method as part of perinatal care to step toward mother and baby health.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences approved the study (Code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1399.471). Written informed consent was taken from all participants in the study, and they were assured that their personal information would remain confidential. Also, exercise therapy was carried out for the control group after the study.

Funding

This project was funded by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, and administration: Saeideh Sabzee, Farideh Kazemi and Seyedeh Zahra Masoumi; Data collection: Saeideh Sabzee; Data analysis: Farideh Kazemi; Writing the manuscript: Mansoureh Refaei and Mohammad Haghighi; Review, editing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, esteemed professors, participants, and other people who helped us in this study are deeply appreciated.

References

- Yang Y, Li W, Ma TJ, Zhang L, Hall BJ, Ungvari GS, et al. Prevalence of poor sleep quality in perinatal and postnatal women: A comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Psychiatry. 2020; 11:161. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00161] [PMID]

- Amel Barez M, Babazadeh R, Latifnejad Roudsari R, Mousavi Bazaz M, Mirzaii Najmabadi K. Women’s strategies for managing domestic violence during pregnancy: A qualitative study in Iran. Reprod Health. 2022; 19(1).58: [DOI:10.1186/s12978-021-01276-8] [PMID]

- Karimi A, Daliri S, Sayehmiri K. [The prevalence of physical and psychological violence during pregnancy in Iran and the world: A systematic review and meta-analysis (Persian)]. J Clin Nurs Midwifery. 2016; 5(3):73-88. [Link]

- Ghazanfarpour M, Khadivzadeh T, Rajab Dizavandi F, Kargarfard L, Shariati Kh, Saeidi M. The relationship between abuse during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes: An Overview of meta analysis. Int J Pediatr. 2018; 6(10):8399-405. [DOI:10.22038/ijp.2018.31446.2787]

- D'Angelo DV, Bombard JM, Lee RD, Kortsmit K, Kapaya M, Fasula A. Prevalence of experiencing physical, emotional, and sexual violence by a current intimate partner during pregnancy: Population-based estimates from the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. J Fam Violence. 2022; 38(1):117-26. [DOI:10.1007/s10896-022-00356-y] [PMID]

- Buchanan F, Humphreys C. Coercive control during pregnancy, birthing and postpartum: Women’s experiences and perspectives on health practitioners’ responses. J Fam Violence. 2021; 36:325-35. [DOI:10.1007/s10896-020-00161-5]

- Niazi M, Kassani A, Menati R, Khammarnia M. [The prevalence of domestic violence among pregnant women in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis (Persian)]. Sadra Med J. 2015; 3(2):130-50. [Link]

- Bazyar J, Safarpour H, Daliri S, Karimi A, Safi Keykaleh M, Bazyar M. The prevalence of sexual violence during pregnancy in Iran and the world: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Inj Violence Res. 2018; 10(2):63-74. [DOI:10.5249/jivr.v10i2.954] [PMID]

- Garrido-Macías M, Valor-Segura I, Expósito F. Exposito, Women’s experience of sexual coercion and reactions to intimate partner sexual violence. J Interpers Violence. 2022; 37(11-12):NP8965-88. [DOI:10.1177/0886260520980394] [PMID]

- Zargarinejad F, Ahmadi M. [The mediating role of sexual self-schema in the relationship of sexual functioning with sexual satisfaction in married female college students (Persian)]. Iran J Psychiatr Clin Psychol. 2020; 25(4):412-27. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.25.4.5]

- Peixoto MM, Lopes J. Sexual functioning beliefs, sexual satisfaction, and sexual functioning in women: A cross-sectional mediation analysis.J Sex Med. 2023; 20(2):170-6. [DOI:10.1093/jsxmed/qdac014] [PMID]

- Babaheidarian F, Masoumi SZ, Sangestani G, Roshanaei G. The effect of family-based counseling on domestic violence in pregnant women referring to health centers in Sahneh city, Iran, 2018. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2021; 20(1):11. [PMID]

- Poorheidari M, Ganji J, Hasani-Moghadam S, Azizi M, Alijani F. The effects of relationship enrichment counseling on marital satisfaction among infertile couples with a history of domestic violence. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2021; 8(1):1-8. [DOI:10.4103/JNMS.JNMS_21_20]

- Lund JI, Kleinplatz PJ, Charest M, Huber JD. The relationship between the sexual self and the experience of pregnancy. J Perinat Educ. 2019; 28(1):43-50. [DOI:10.1891/1058-1243.28.1.43] [PMID]

- Del Río Olvera FJ, Sánchez-Sandoval Y, García-Rojas AD, Rodríguez-Vargas S, Ruiz-Ruiz J. The prevalence of the risk of sexual dysfunction in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy in a sample of Spanish Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023; 20(5):3955. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20053955] [PMID]

- Tafreshi M, Amiri Majd M, Jafari A. [The effectiveness of anger management skills training on reduction family violence and recovery marital satisfaction (Persian)]. J Family Res. 2013; 9(3):299-310. [Link]

- Sheikhan Z, Ozgoli G. Domestic violence in Iranian infertile women. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014; 28(1):1023-31. [Link]

- Ziaei T, Khoei EM, Salehi M, Farajzadegan Z. Psychometric properties of the Farsi version of modified Multidimensional Sexual Self-concept Questionnaire. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013; 18(6):439-45. [PMID]

- Stanback J, Steiner M, Dorflinger L, Solo J, Cates W Jr. WHO tiered-effectiveness counseling is rights-based family planning. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015; 3(3):352-7. [DOI:10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00096] [PMID]

- Daley D, McCauley M, van den Broek N. Interventions for women who report domestic violence during and after pregnancy in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic literature review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20(1):141. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-2819-0] [PMID]

- Schneider M, Hirsch JS. Comprehensive sexuality education as a primary prevention strategy for sexual violence perpetration. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2020; 21(3):439-55. [DOI:10.1177/1524838018772855] [PMID]

- Alizadeh S, Riazi H, Majd HA, Ozgoli G. The effect of sexual health education on sexual activity, sexual quality of life, and sexual violence in pregnancy: A prospective randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021; 21(1):334. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-021-03803-8] [PMID]

- Mohammadbeigi A, Seyedi S, Behdari M, Brojerdi R, Rezakhoo A. [The effect of life skills training on decreasing of domestic violence and general health promotion of women (Prsian)]. Nurs Midwifery J. 2016; 13(10):903-11. [Link]

- Okore C, Asatsa S, Ntarangwe M. The effect of social skills training on self concept of teenage mothers, a case study of training college in Kenya. Int J Soc Sci Econ Rev. 2021; 3(2):1-09. [DOI:10.36923/ijsser.v3i2.102]

- Mohagheghian M, Kajbaf MB, Maredpour A. The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on sexual arousal, intimacy and self-concept of female sexual interest/arousal disorder, a randomized controlled trial. Int J Appl Behav Sci. 2021; 8(1):50-9. [DOI:10.22037/ijabs.v8i1.33225]

- Gordani N, Ziaei T, Naghi Nasab Ardehaei F, Behnampour N, Gharahjeh S. Effect of mood regulation skill training on general and sexual self-concept of infertile women. J Res Dev Nurs Midw. 2021; 18(1):58-62. [DOI:10.52547/jgbfnm.18.1.58]

- Doremami F, Salimi H, Heidari Z, Torabi F. The relationship between sexual self-concept and contraception sexual behavior in 15 to 49 years old women covered by community health centers. J Educ Health Promot. 2023; 12:27. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_1185_21] [PMID]

- Bavi A, Amanallahi A, Attari Y. The relationship between sexual self-concept and sexual performance of married women who refer to health centers in Ahvaz. Jundishapur Sci Med J. 2014; 13(4):485-93. [Link]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2023/09/18 | Accepted: 2023/09/3 | Published: 2023/09/3

Received: 2023/09/18 | Accepted: 2023/09/3 | Published: 2023/09/3

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |