Wed, Jan 28, 2026

Volume 36, Issue 1 (1-2026)

JHNM 2026, 36(1): 63-71 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shahrokhi Nia S, Marashi T, Namdari M, Shahry P. Readiness for Marriage and Contributory Factors in Premarital Counseling Attendee in Tehran, Iran. JHNM 2026; 36 (1) :63-71

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2201-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2201-en.html

1- Health Education and promotion (MSC), Department of Public Health, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,t.marashi@sbmu. ac.ir

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Biostatistics, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences Tehran, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Social Determinants of health Research Center, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Assistant Professor, Department of Biostatistics, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences Tehran, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Social Determinants of health Research Center, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 622 kb]

(42 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (70 Views)

References

Full-Text: (4 Views)

Introduction

Marriage is one of the most important events in a person’s life, a turning point, and the foundation for building a family. In many countries, it is the only accepted institution for childbearing [1]. This important event in human life affects the health of couples [2] and is an important determinant of their physical health and even mortality [3]. Readiness for and attitudes about marriage are key variables in an individual’s decision to marry, and are important predictors of subsequent marital satisfaction [4]. Premarital counseling programs can improve attitudes towards marriage [5]. Premarital counseling is a relatively new approach that is being implemented in many countries to prepare young men and women for living together, prevent dissatisfaction and failure in marital life, and have a suitable marriage [6, 7]. It allows them to start living together with greater awareness and knowledge about themselves and their future spouse, as well as the importance and goals of marriage [8]. There are many studies in this field, and their results indicate a significant increase in couples’ knowledge and awareness after counseling [9]. A study showed that couples who received premarital counseling had a 31% lower risk of marriage failure [7, 10]. According to statistics from the National Organization for Civil Registration of Iran, over the last 4 years, 1 in 4 marriages has ended in divorce [11]. Marriage requires specific skills and resources, including internal preparations (such as emotional readiness, social readiness, emotional health, being of sufficient age, relationships with the opposite sex, readiness to accept responsibilities) and external preparations (such as financial readiness, planning for various responsibilities) [12]. In other studies, individual factors, couples’ relationships, couples’ family, cultural/social/economic factors, religiosity, job, spouse’s job, and field of study have been considered as factors related to the success of marriage [13]. Factors such as moral readiness, marriage planning, interpersonal readiness, readiness for life skills, mental/financial/physical/intellectual readiness [14] as well as commitment to the relationship are essential for marriage preparation [15]. Although marriage readiness is crucial for creating healthy marriages and reducing divorce rates [16, 17], most young people ignore it and are unaware of its importance [18]. On the other hand, various factors can be related to readiness for marriage. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the level of readiness for marriage and its relationship with sociodemographic factors among individuals with the intention to marry, attending premarital counseling centers in Tehran, Iran.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study. The study population consists of all individuals referring to the premarital counseling centers affiliated with Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, in 2021. Of these, on 492 individuals (246 couples) with the intention to marry were selected. The sample size was determined based on the highest standard deviation for marriage readiness (SD=4) reported in Bestooh et al.’s study [19], a 95% Confidence Level (CI), and a 0.5 error probability. Sampling was carried out using a cluster sampling method in two stages. In the first stage, four premarital counseling centers were randomly selected from among 14 centers. In the second stage, samples were selected from each center using convenience sampling. In this regard, 62 individuals were selected from the first center, 62 from the second center, 62 from the third center, and 60 from the fourth center. Inclusion criteria were Iranian nationality, no prior marriage experience, and the ability to read and write in Persian.

The data collection tools were a sociodemographic form (surveying age, gender, educational level, and occupation) and the criteria for marriage readiness questionnaire (CMRQ) developed by Carroll et al. [20] with 39 items and six domains: Norm compliance (7 items), family capacities (8 items), role transitions (6 items), intrapersonal competence (6 items), interpersonal competence (8 items), and sexual experience (4 items). The scoring is as follows: 1 (not important), 2 (less important), 3 (quite important), and 4 (very important). The total score ranges from 39 to 156, with higher scores indicating greater levels of marriage readiness. The Persian version of this tool has been validated by Bestooh et al. [19]. The Cronbach’s α coefficient values for the six domains ranged from 0.80 to 0.82; the overall scale’s coefficient is 0.86.

To collect data, after obtaining the necessary permits, the researcher visited the selected premarital counseling centers daily, except on holidays, and sampling was conducted according to the inclusion criteria. During sampling, the study objectives and methods were first explained to the participants and when they were willing to participate in the study, an informed consent form was signed by them. The questionnaires were completed independently by both spouses. Sampling continued from May to September 2021.

Data analysis was performed in SPSS software, version 21. Initially, the data were reported using descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, Mean±SD. After examining the normality of the data (using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), independent t-tests and Analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare the CMRQ scores between men and women, between employed and unemployed individuals, and between individuals with different levels of education. To examine the relationship between individuals’ age and the CMRQ score, the Pearson correlation test was used. Linear regression analysis was used to identify the factors predicting the CMRQ score. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Among 492 individuals (246 couples), most of the women were in the age group of 20-24 years (mean age=26±5.88), and most of the men were in the age group of 25-29 years (mean age=29.12±4.98 years). Most of the women (68.2%) and men (68.7%) had university education, and few women (10.2%) and men (8.9%) had lower than high school education. Also, 98% of men and 53.2% of women were employed (Table 1).

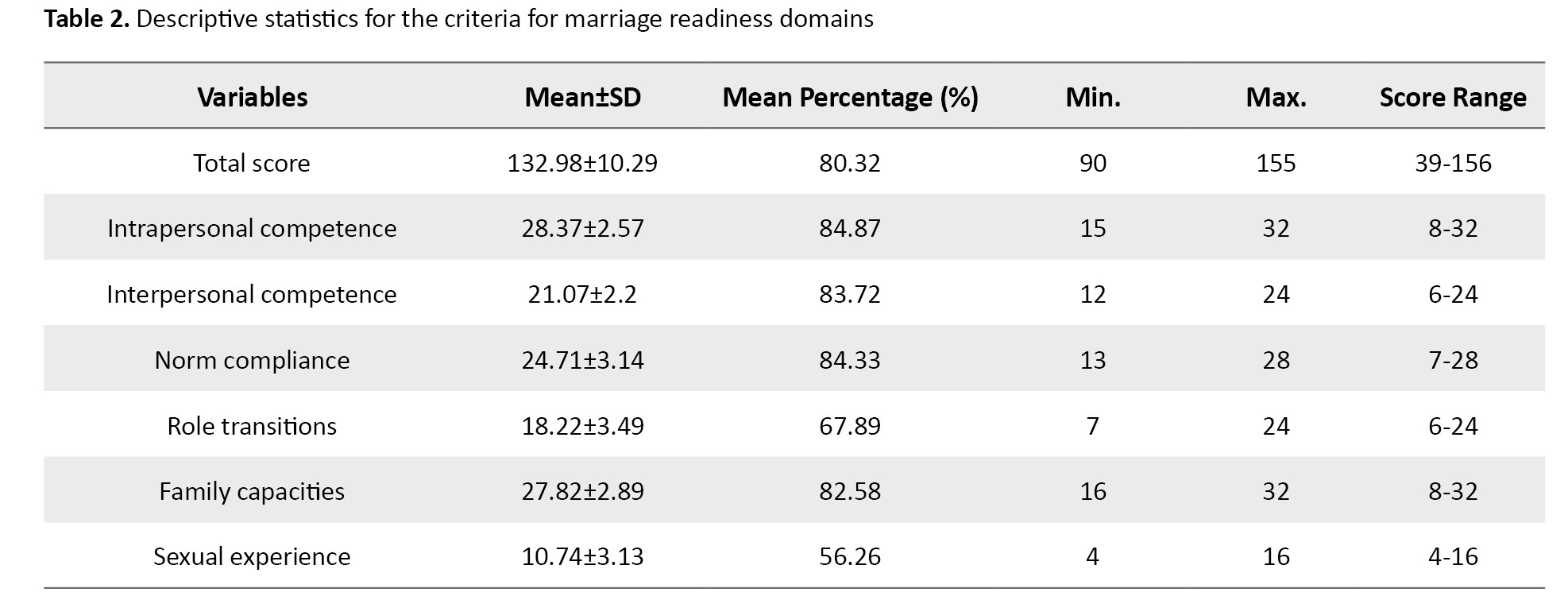

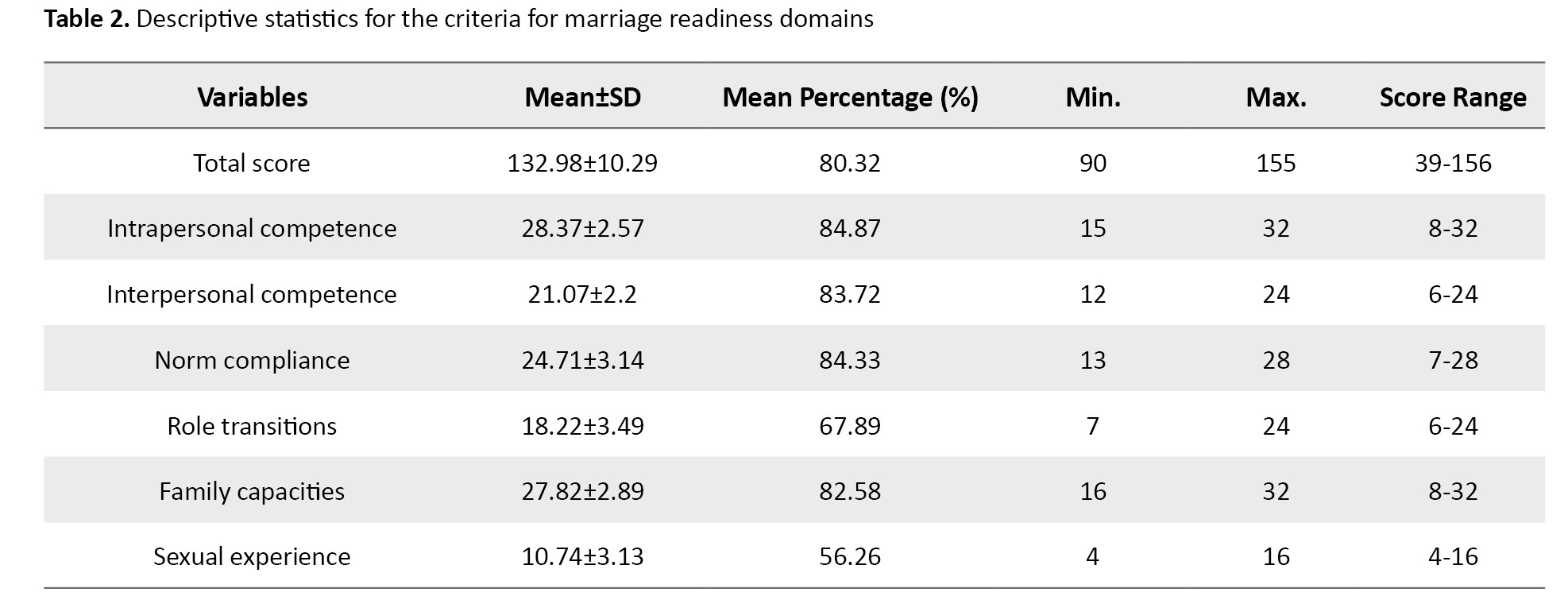

The total CMRQ score was 132.98±10.29, ranging from 90 to 155. The descriptive statistics for the CMRQ domains are presented in Table 2.

To compare the domains, since their score ranges were not equal, the average scores were first calculated as percentages to make them comparable. The two factors “norm compliance” and “intrapersonal competence” had the highest scores of 84.33 and 84.87, respectively, while the “sexual experience” domain had the lowest score (56.26).

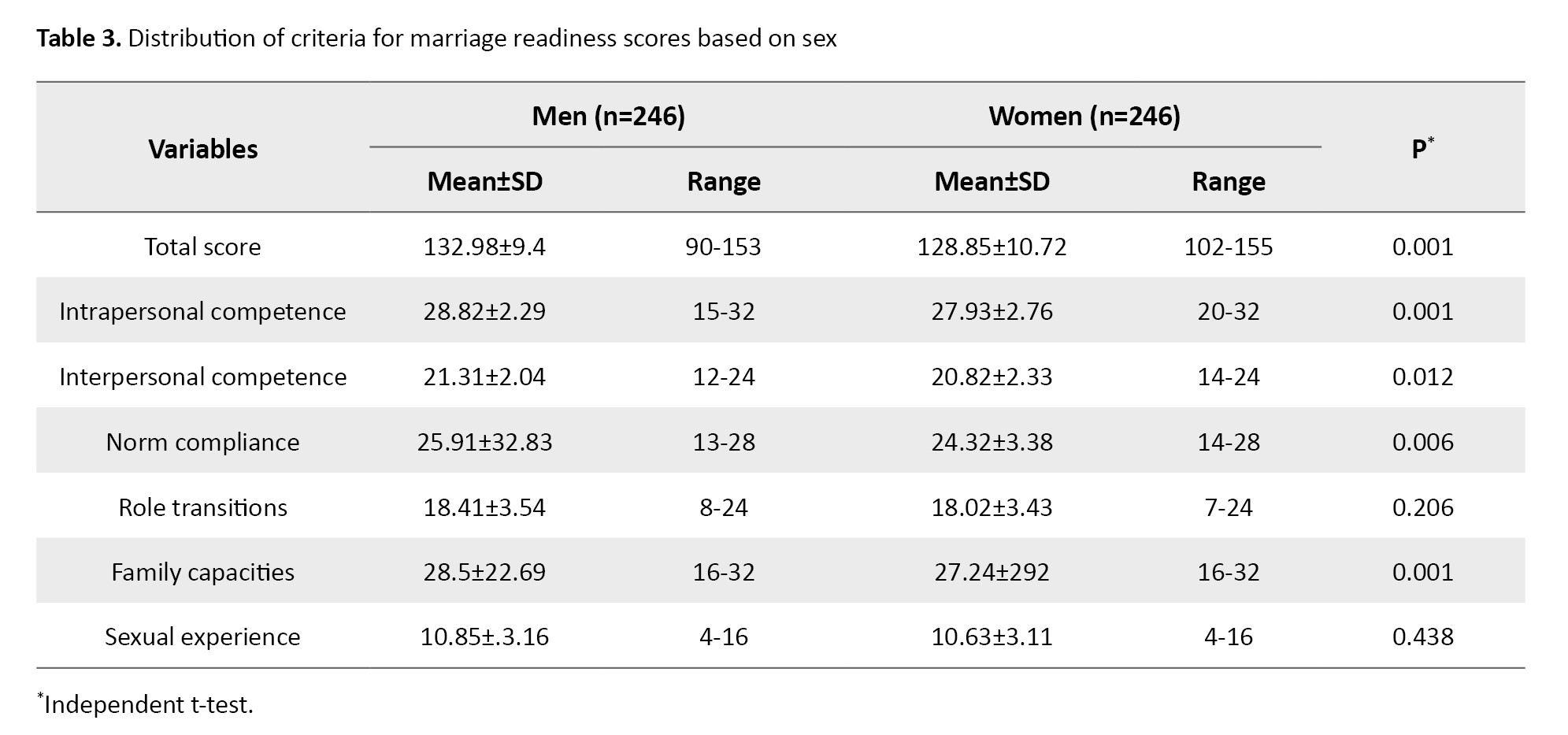

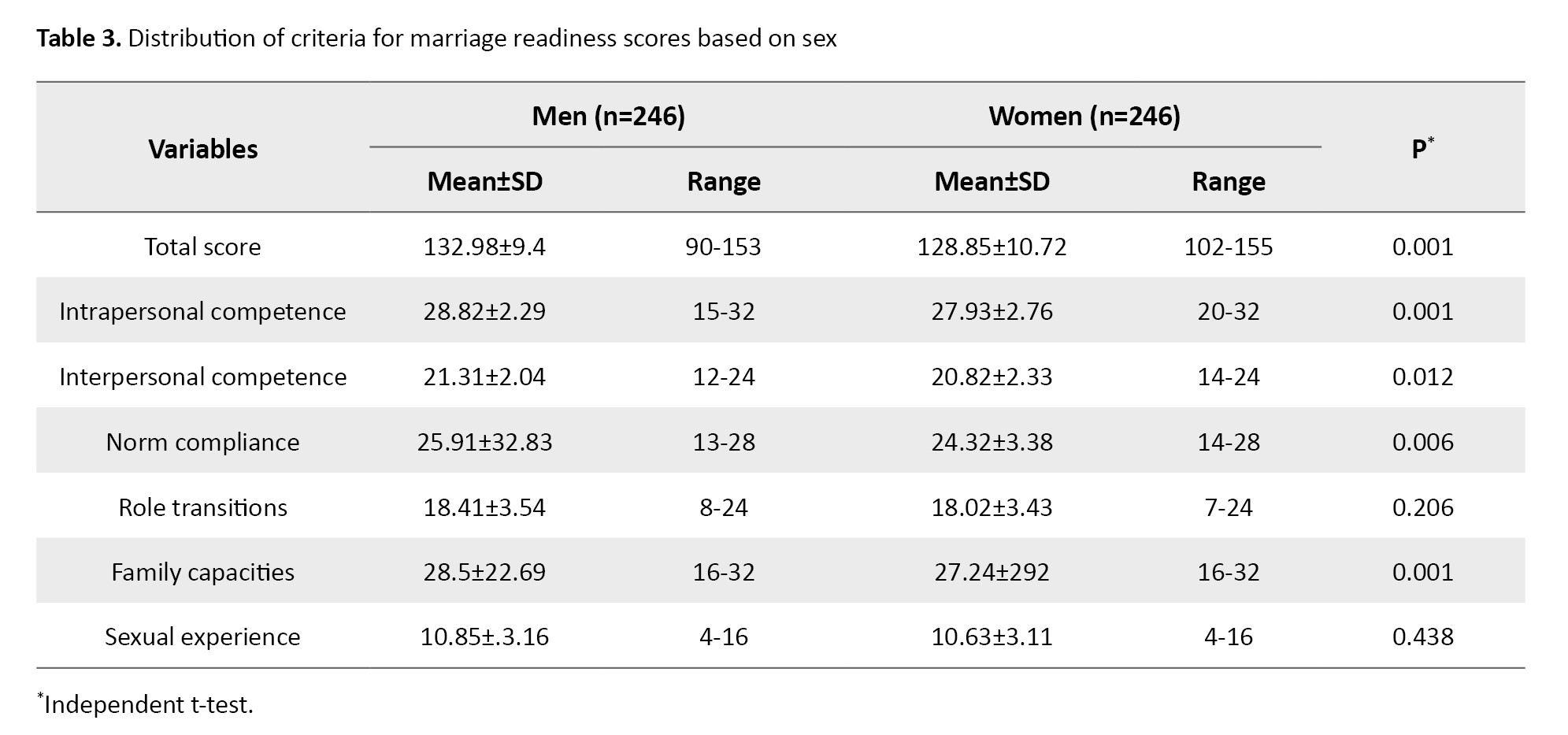

According to the independent t-test results shown in Table 3, across all domains, women’s average scores were significantly higher than men’s (P=0.01), except for the domains of role transitions and sexual experience, where no significant difference was observed.

The mean total CMRQ score in women was 132.98±9.4, and in men was 128.85±10.72. The independent t-test results shown in Table 3 indicated that this difference was statistically significant (P=0.001).

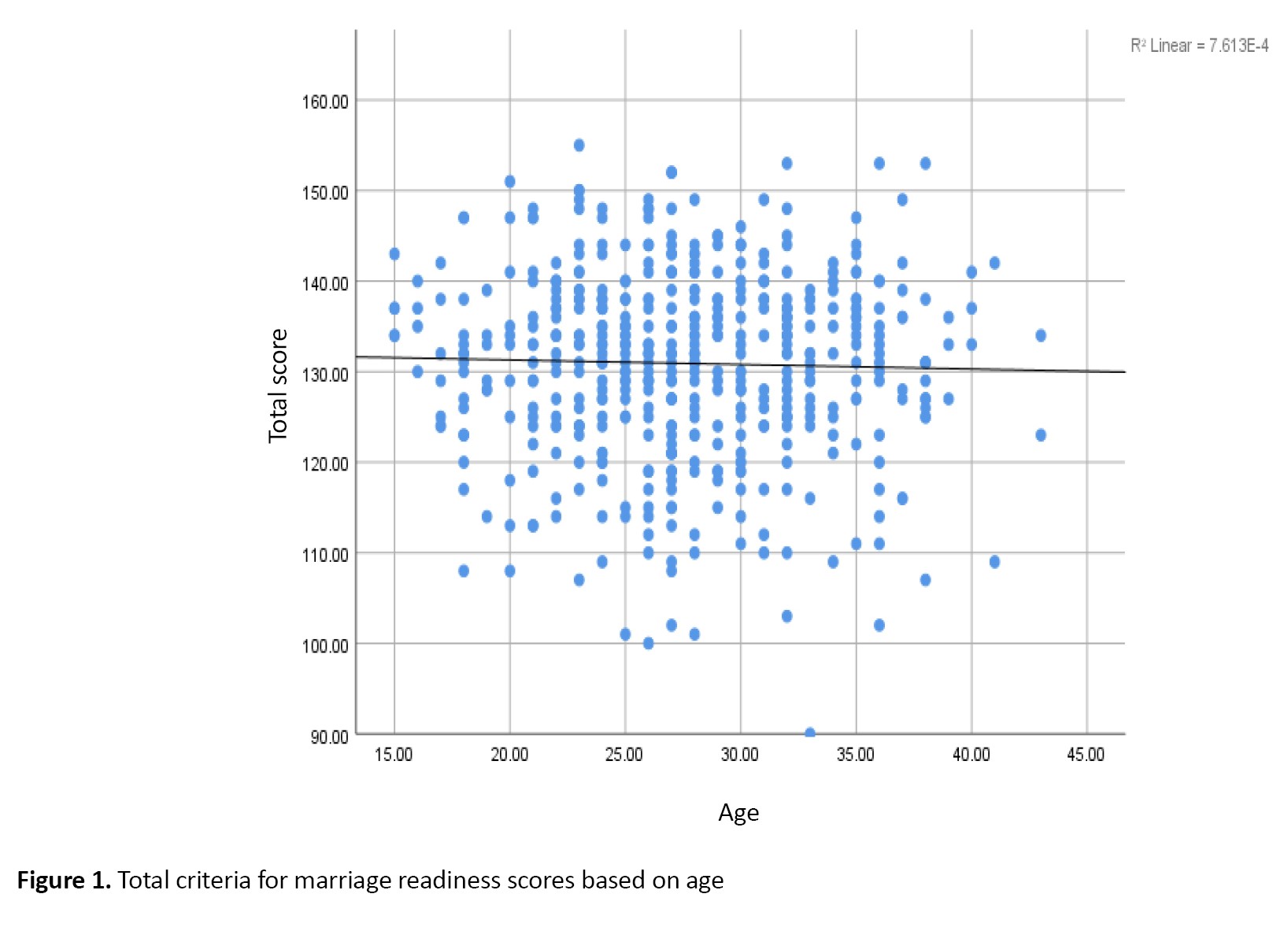

Figure 1 is a dot chart showing the correlation between the total CMRQ score and age.

Marriage is one of the most important events in a person’s life, a turning point, and the foundation for building a family. In many countries, it is the only accepted institution for childbearing [1]. This important event in human life affects the health of couples [2] and is an important determinant of their physical health and even mortality [3]. Readiness for and attitudes about marriage are key variables in an individual’s decision to marry, and are important predictors of subsequent marital satisfaction [4]. Premarital counseling programs can improve attitudes towards marriage [5]. Premarital counseling is a relatively new approach that is being implemented in many countries to prepare young men and women for living together, prevent dissatisfaction and failure in marital life, and have a suitable marriage [6, 7]. It allows them to start living together with greater awareness and knowledge about themselves and their future spouse, as well as the importance and goals of marriage [8]. There are many studies in this field, and their results indicate a significant increase in couples’ knowledge and awareness after counseling [9]. A study showed that couples who received premarital counseling had a 31% lower risk of marriage failure [7, 10]. According to statistics from the National Organization for Civil Registration of Iran, over the last 4 years, 1 in 4 marriages has ended in divorce [11]. Marriage requires specific skills and resources, including internal preparations (such as emotional readiness, social readiness, emotional health, being of sufficient age, relationships with the opposite sex, readiness to accept responsibilities) and external preparations (such as financial readiness, planning for various responsibilities) [12]. In other studies, individual factors, couples’ relationships, couples’ family, cultural/social/economic factors, religiosity, job, spouse’s job, and field of study have been considered as factors related to the success of marriage [13]. Factors such as moral readiness, marriage planning, interpersonal readiness, readiness for life skills, mental/financial/physical/intellectual readiness [14] as well as commitment to the relationship are essential for marriage preparation [15]. Although marriage readiness is crucial for creating healthy marriages and reducing divorce rates [16, 17], most young people ignore it and are unaware of its importance [18]. On the other hand, various factors can be related to readiness for marriage. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the level of readiness for marriage and its relationship with sociodemographic factors among individuals with the intention to marry, attending premarital counseling centers in Tehran, Iran.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study. The study population consists of all individuals referring to the premarital counseling centers affiliated with Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, in 2021. Of these, on 492 individuals (246 couples) with the intention to marry were selected. The sample size was determined based on the highest standard deviation for marriage readiness (SD=4) reported in Bestooh et al.’s study [19], a 95% Confidence Level (CI), and a 0.5 error probability. Sampling was carried out using a cluster sampling method in two stages. In the first stage, four premarital counseling centers were randomly selected from among 14 centers. In the second stage, samples were selected from each center using convenience sampling. In this regard, 62 individuals were selected from the first center, 62 from the second center, 62 from the third center, and 60 from the fourth center. Inclusion criteria were Iranian nationality, no prior marriage experience, and the ability to read and write in Persian.

The data collection tools were a sociodemographic form (surveying age, gender, educational level, and occupation) and the criteria for marriage readiness questionnaire (CMRQ) developed by Carroll et al. [20] with 39 items and six domains: Norm compliance (7 items), family capacities (8 items), role transitions (6 items), intrapersonal competence (6 items), interpersonal competence (8 items), and sexual experience (4 items). The scoring is as follows: 1 (not important), 2 (less important), 3 (quite important), and 4 (very important). The total score ranges from 39 to 156, with higher scores indicating greater levels of marriage readiness. The Persian version of this tool has been validated by Bestooh et al. [19]. The Cronbach’s α coefficient values for the six domains ranged from 0.80 to 0.82; the overall scale’s coefficient is 0.86.

To collect data, after obtaining the necessary permits, the researcher visited the selected premarital counseling centers daily, except on holidays, and sampling was conducted according to the inclusion criteria. During sampling, the study objectives and methods were first explained to the participants and when they were willing to participate in the study, an informed consent form was signed by them. The questionnaires were completed independently by both spouses. Sampling continued from May to September 2021.

Data analysis was performed in SPSS software, version 21. Initially, the data were reported using descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, Mean±SD. After examining the normality of the data (using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), independent t-tests and Analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare the CMRQ scores between men and women, between employed and unemployed individuals, and between individuals with different levels of education. To examine the relationship between individuals’ age and the CMRQ score, the Pearson correlation test was used. Linear regression analysis was used to identify the factors predicting the CMRQ score. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Among 492 individuals (246 couples), most of the women were in the age group of 20-24 years (mean age=26±5.88), and most of the men were in the age group of 25-29 years (mean age=29.12±4.98 years). Most of the women (68.2%) and men (68.7%) had university education, and few women (10.2%) and men (8.9%) had lower than high school education. Also, 98% of men and 53.2% of women were employed (Table 1).

The total CMRQ score was 132.98±10.29, ranging from 90 to 155. The descriptive statistics for the CMRQ domains are presented in Table 2.

To compare the domains, since their score ranges were not equal, the average scores were first calculated as percentages to make them comparable. The two factors “norm compliance” and “intrapersonal competence” had the highest scores of 84.33 and 84.87, respectively, while the “sexual experience” domain had the lowest score (56.26).

According to the independent t-test results shown in Table 3, across all domains, women’s average scores were significantly higher than men’s (P=0.01), except for the domains of role transitions and sexual experience, where no significant difference was observed.

The mean total CMRQ score in women was 132.98±9.4, and in men was 128.85±10.72. The independent t-test results shown in Table 3 indicated that this difference was statistically significant (P=0.001).

Figure 1 is a dot chart showing the correlation between the total CMRQ score and age.

The Pearson correlation test results showed no statistically significant relationship between them. The results of the one-way ANOVA test did not show a significant difference in the mean total CMRQ score based on educational level. The mean total CMRQ score in employed individuals was 130.64±10.39, and in unemployed individuals was 131.58±10.04. According to the result of the independent t-test, there was no significant difference.

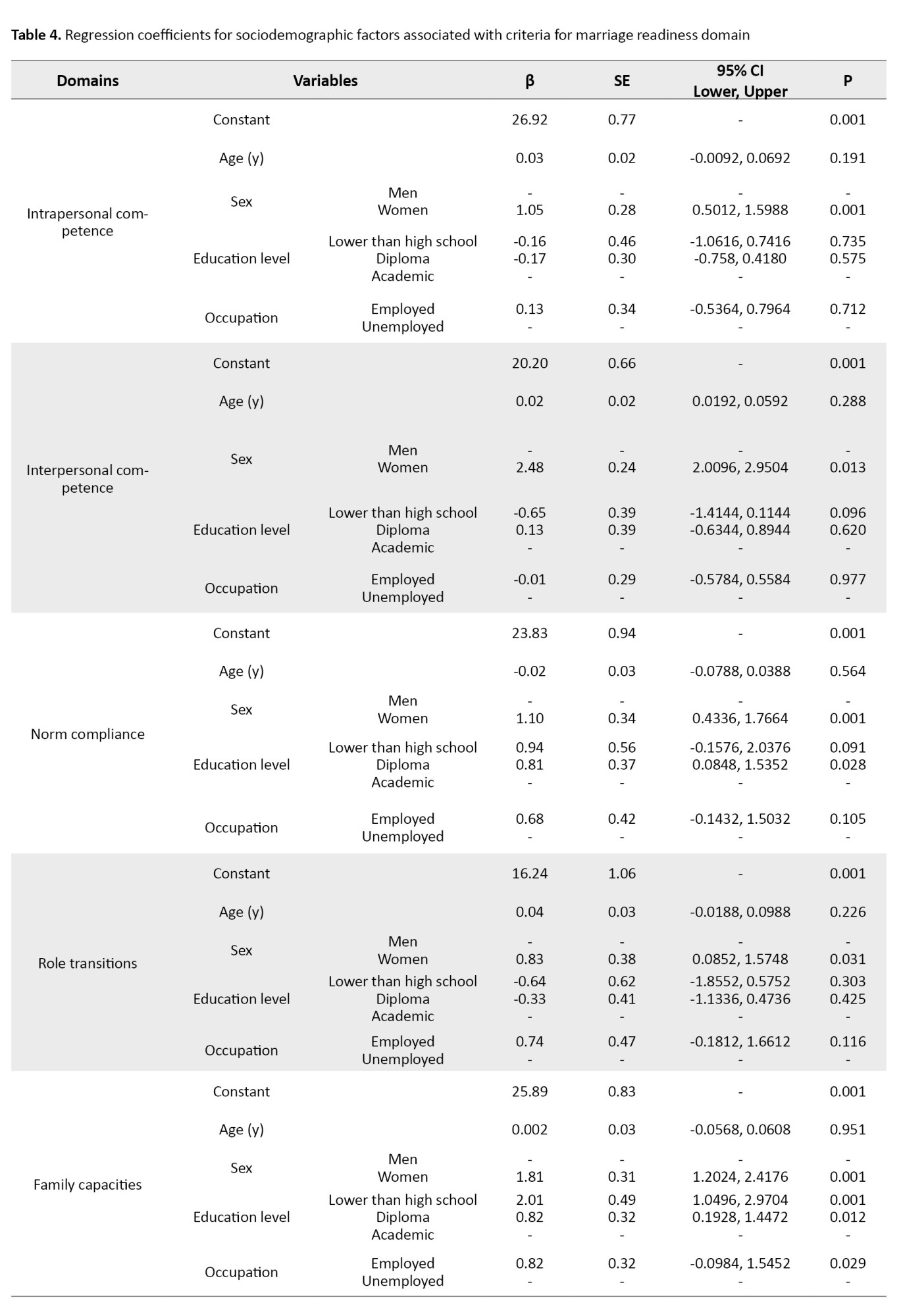

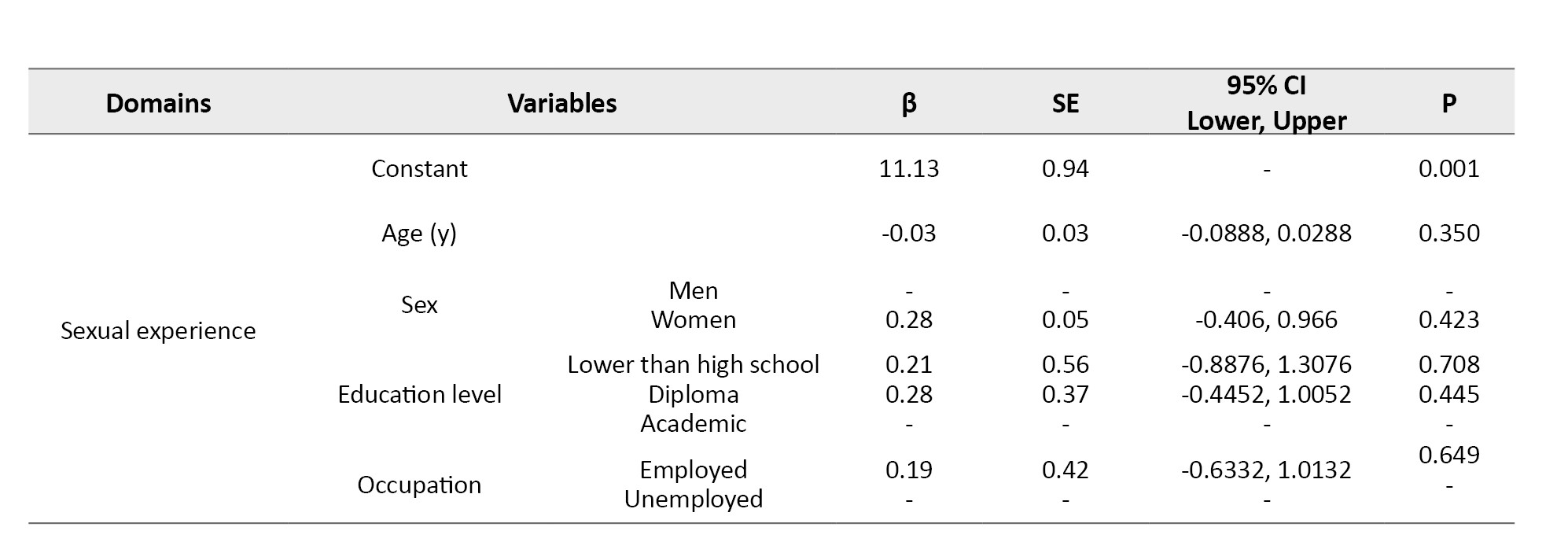

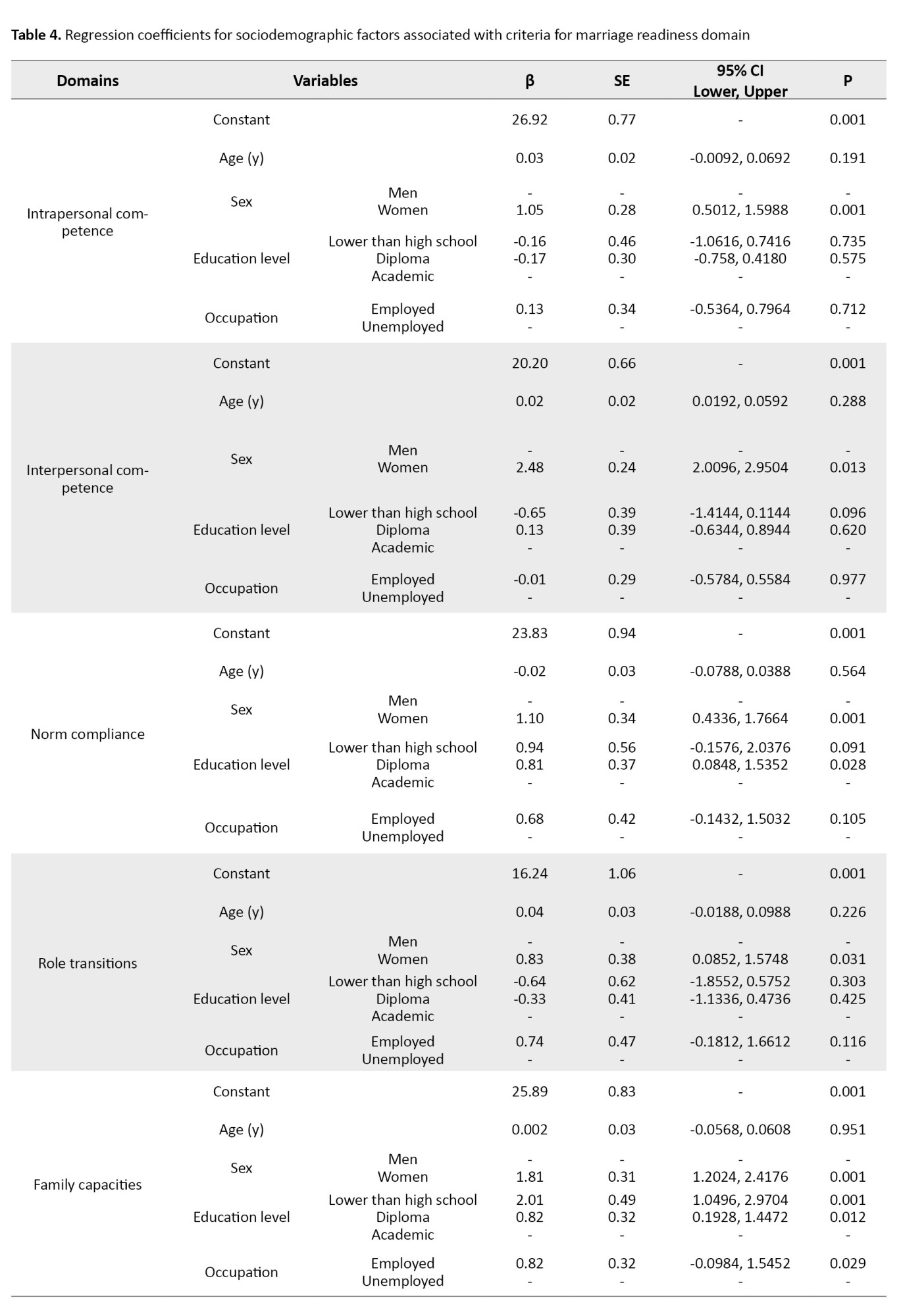

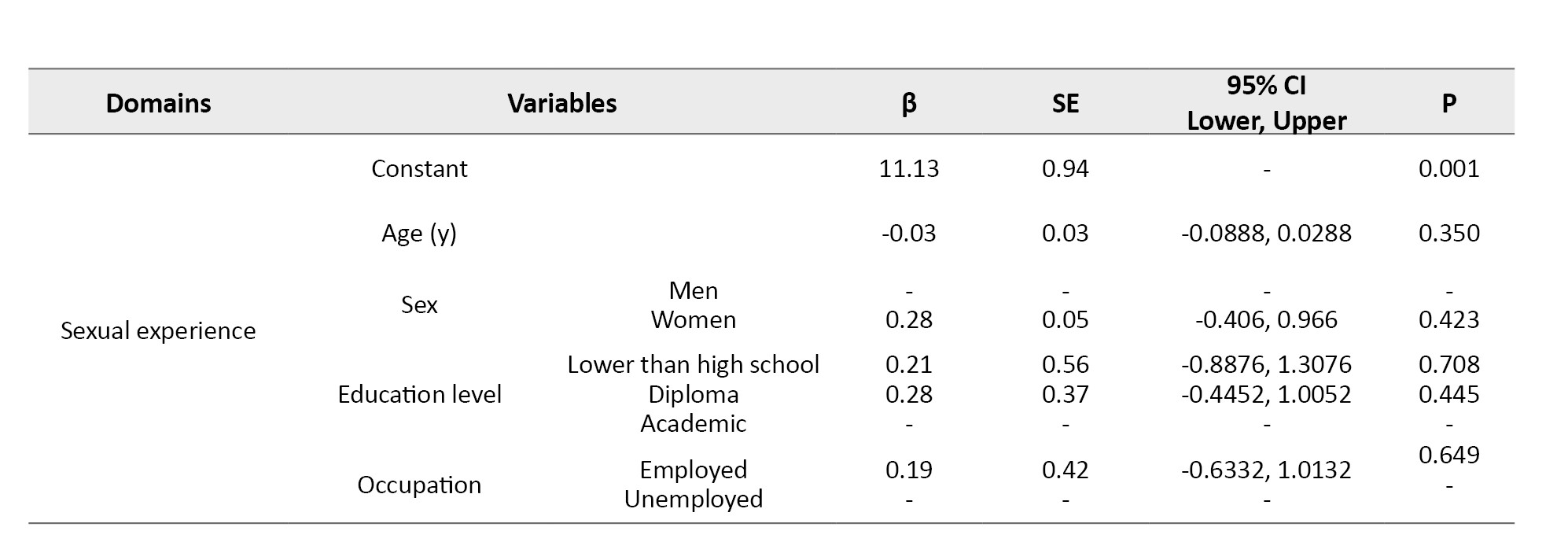

The results of regression analysis showed that only the sex variable had a significant association with the total CMRQ score (P=0.001). The total score in women was 5.67 units higher than that in men. Regarding the CMRQ domains, the female gender had a significant association with intrapersonal competence (P=0.001). Its score in women was 1.05 units higher than that in men. Also, it had a significant association with norm compliance (P=0.001). Its score in women was 1.1 units higher than that in men. Educational level had also had a significant association with norm compliance; the score in individuals with a high school diploma was 0.81 units higher than that in those with an academic degree. Sex, educational level, and occupation were significantly associated with family capacities. Its score in women was 1.81 units higher than in men. In those with lower than high school education, the family capacities score was 2.01 units higher than that in those with an academic degree; in those with a high school diploma, it was higher by 0.82 units. Moreover, the employment increased the family capacities score by 0.82 units. The female gender also had a significant association with the role transitions score (P=0.031). Its score in women was 0.83 units higher than that in men. None of the sociodemographic variables showed a significant association with the sexual experience score.

Overall, the female gender was the significant predictor of interpersonal competence (β=2.48, 95% CI; 2.0096%, 2.9504%, P=0.013), norm compliance (β=1.10, 95% CI; 0.4336%, 1.7664%, P=0.001), role transitions (β=0.83, 95% CI; 0.0852%, 1.5748%, P=0.031), and family capacities (β=1.81, 95% CI; 1.2024%, 2.4176%, P=0.001). Employment was the significant predictor of family capacities (β=0.82, 95% CI; 0.0984%, 1.5452%, P=0.029). These results were shown in Table 4.

Discussion

Based on the results obtained, the marriage readiness of individuals with the intention to marry in Tehran was high. This indicates that the participants consider themselves ready to accept the responsibilities and challenges of married life. This result is consistent with the result of Karunia and Rahaju, who reported a relatively high level of marriage readiness [21]. Also, based on the findings, the total marriage readiness score of women was significantly higher than that of men, indicating that women were readier for marriage. This finding is contrary to the results of Ismail, who showed sex had no relationship with readiness for marriage [22]. It seems that, due to physiological differences and faster mental and physical maturation in women, as well as the upbringing customs in Iranian culture, women assume greater responsibility and are therefore more ready for marriage. In similar studies, women were also more ready for marriage [23, 21].

Marriage, as a step into living with a partner, requires intrapersonal competence, and the more this competence a person has, the higher their readiness for marriage. Our results regarding intrapersonal competence are consistent with the results of Mousavi and Gholinasab [24]. Interpersonal competence, which is related to individuals’ moral health, was also identified in a similar study as an important criterion for marriage readiness [25]. In our study, the average score of family capacities was 27.82, which is close to the score reported by Bestooh et al. (23.26) [19]. After marriage, couples have specific responsibilities, and they are expected to fulfill them well. In the study by Stinnette [26], marital competence was identified as one of the keys to successful marriage or readiness for marriage.

According to the results, the score of role transitions domain, which includes role change priorities such as having a job, buying a house, completing education, was 18.22. This is close to the score reported in Bestooh et al.’s study [19]. Financial problems and concerns about career, education, and housing are among the most important issues related to preparation for marriage [27]. Participants’ scores in the norm compliance domain were high. People who comply with social norms, observe the rules, and behave more responsibly within social frameworks also adhere to norms regarding marriage and married life, and enter the stage of family formation more easily. The sexual experience domain had a lower score than other domains of marriage readiness in our study. According to Lacey et al. [28], sexual desire is significantly associated with measures of readiness for marriage. Carroll et al. showed that having sexual experience helps to have a better married life in the future [29]. In our study, participants who reported readiness were in their mid-thirties. A study by Gholamaliee et al. showed that people living in urban areas marry at older ages [30]. The results are also consistent with the results of other studies [29-32]. Older people have greater emotional maturity, more social experience, and more suitable jobs and income; therefore, they are better prepared to marry.

In our study, no significant difference was found in the total score of marriage readiness based on educational level; all participants considered education a prerequisite for marriage readiness, which is consistent with the results of similar studies [33, 29]. Education can improve communication skills and self-confidence, and it is generally believed that educated people have a higher social status. Our results showed no significant difference in the total score of marriage readiness based on occupation (employed/unemployed), which is contrary to the results of similar studies [29, 33, 34]. Having a stable job is important for a man to be ready for marriage. Perhaps since the premarital counseling centers were located in areas where residents were economically better off, having a job was not a criterion for marriage readiness. Among the sociodemographic variables, only sex (female gender) showed a significant association with role transitions, consistent with results of other studies [35, 36].

One limitation of this study is that, since it was conducted in Tehran and the samples were selected from premarital counseling centers, the findings may not be generalized to all people in Iran. Therefore, it is recommended that studies be conducted in other cities in Iran with diverse ethnic and cultural populations. Given the lower readiness of men for marriage in this study and the university education of the majority of participants, educational interventions can be designed and implemented at universities for male students to improve their readiness, tailored to the age and conditions of the students. In addition, holding marriage preparation classes with the presence of both sexes at universities can be effective in increasing their understanding of marriage and their readiness for it. The expansion of marriage counseling centers can greatly help young people make marriage decisions with greater preparation.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1400.018). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and they were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This article was extracted from a master’s thesis of Sima Shahrokhi Nia, approved by the Department of Public Health, School of Public Health and Safety, SShahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The study was funded by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Sima Shahrokhi Nia, Tayebeh Marashi, and Nastaran Keshavarz; Data collection: Sima Shahrokhi Nia; Statistical analyses: Mahshid Namdari; Writing the original draft: Sima Shahrokhi Nia and Tayebeh Marashi; Review, editing, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation in this study.

The results of regression analysis showed that only the sex variable had a significant association with the total CMRQ score (P=0.001). The total score in women was 5.67 units higher than that in men. Regarding the CMRQ domains, the female gender had a significant association with intrapersonal competence (P=0.001). Its score in women was 1.05 units higher than that in men. Also, it had a significant association with norm compliance (P=0.001). Its score in women was 1.1 units higher than that in men. Educational level had also had a significant association with norm compliance; the score in individuals with a high school diploma was 0.81 units higher than that in those with an academic degree. Sex, educational level, and occupation were significantly associated with family capacities. Its score in women was 1.81 units higher than in men. In those with lower than high school education, the family capacities score was 2.01 units higher than that in those with an academic degree; in those with a high school diploma, it was higher by 0.82 units. Moreover, the employment increased the family capacities score by 0.82 units. The female gender also had a significant association with the role transitions score (P=0.031). Its score in women was 0.83 units higher than that in men. None of the sociodemographic variables showed a significant association with the sexual experience score.

Overall, the female gender was the significant predictor of interpersonal competence (β=2.48, 95% CI; 2.0096%, 2.9504%, P=0.013), norm compliance (β=1.10, 95% CI; 0.4336%, 1.7664%, P=0.001), role transitions (β=0.83, 95% CI; 0.0852%, 1.5748%, P=0.031), and family capacities (β=1.81, 95% CI; 1.2024%, 2.4176%, P=0.001). Employment was the significant predictor of family capacities (β=0.82, 95% CI; 0.0984%, 1.5452%, P=0.029). These results were shown in Table 4.

Discussion

Based on the results obtained, the marriage readiness of individuals with the intention to marry in Tehran was high. This indicates that the participants consider themselves ready to accept the responsibilities and challenges of married life. This result is consistent with the result of Karunia and Rahaju, who reported a relatively high level of marriage readiness [21]. Also, based on the findings, the total marriage readiness score of women was significantly higher than that of men, indicating that women were readier for marriage. This finding is contrary to the results of Ismail, who showed sex had no relationship with readiness for marriage [22]. It seems that, due to physiological differences and faster mental and physical maturation in women, as well as the upbringing customs in Iranian culture, women assume greater responsibility and are therefore more ready for marriage. In similar studies, women were also more ready for marriage [23, 21].

Marriage, as a step into living with a partner, requires intrapersonal competence, and the more this competence a person has, the higher their readiness for marriage. Our results regarding intrapersonal competence are consistent with the results of Mousavi and Gholinasab [24]. Interpersonal competence, which is related to individuals’ moral health, was also identified in a similar study as an important criterion for marriage readiness [25]. In our study, the average score of family capacities was 27.82, which is close to the score reported by Bestooh et al. (23.26) [19]. After marriage, couples have specific responsibilities, and they are expected to fulfill them well. In the study by Stinnette [26], marital competence was identified as one of the keys to successful marriage or readiness for marriage.

According to the results, the score of role transitions domain, which includes role change priorities such as having a job, buying a house, completing education, was 18.22. This is close to the score reported in Bestooh et al.’s study [19]. Financial problems and concerns about career, education, and housing are among the most important issues related to preparation for marriage [27]. Participants’ scores in the norm compliance domain were high. People who comply with social norms, observe the rules, and behave more responsibly within social frameworks also adhere to norms regarding marriage and married life, and enter the stage of family formation more easily. The sexual experience domain had a lower score than other domains of marriage readiness in our study. According to Lacey et al. [28], sexual desire is significantly associated with measures of readiness for marriage. Carroll et al. showed that having sexual experience helps to have a better married life in the future [29]. In our study, participants who reported readiness were in their mid-thirties. A study by Gholamaliee et al. showed that people living in urban areas marry at older ages [30]. The results are also consistent with the results of other studies [29-32]. Older people have greater emotional maturity, more social experience, and more suitable jobs and income; therefore, they are better prepared to marry.

In our study, no significant difference was found in the total score of marriage readiness based on educational level; all participants considered education a prerequisite for marriage readiness, which is consistent with the results of similar studies [33, 29]. Education can improve communication skills and self-confidence, and it is generally believed that educated people have a higher social status. Our results showed no significant difference in the total score of marriage readiness based on occupation (employed/unemployed), which is contrary to the results of similar studies [29, 33, 34]. Having a stable job is important for a man to be ready for marriage. Perhaps since the premarital counseling centers were located in areas where residents were economically better off, having a job was not a criterion for marriage readiness. Among the sociodemographic variables, only sex (female gender) showed a significant association with role transitions, consistent with results of other studies [35, 36].

One limitation of this study is that, since it was conducted in Tehran and the samples were selected from premarital counseling centers, the findings may not be generalized to all people in Iran. Therefore, it is recommended that studies be conducted in other cities in Iran with diverse ethnic and cultural populations. Given the lower readiness of men for marriage in this study and the university education of the majority of participants, educational interventions can be designed and implemented at universities for male students to improve their readiness, tailored to the age and conditions of the students. In addition, holding marriage preparation classes with the presence of both sexes at universities can be effective in increasing their understanding of marriage and their readiness for it. The expansion of marriage counseling centers can greatly help young people make marriage decisions with greater preparation.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1400.018). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and they were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This article was extracted from a master’s thesis of Sima Shahrokhi Nia, approved by the Department of Public Health, School of Public Health and Safety, SShahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The study was funded by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Sima Shahrokhi Nia, Tayebeh Marashi, and Nastaran Keshavarz; Data collection: Sima Shahrokhi Nia; Statistical analyses: Mahshid Namdari; Writing the original draft: Sima Shahrokhi Nia and Tayebeh Marashi; Review, editing, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

- Vannier SA, O’Sullivan LF. Passion, connection, and destiny: How romantic expectations help predict satisfaction and commitment in young adults’ dating relationships. J Soc Pers Relat. 2017; 34(2):235-57. [DOI:10.1177/0265407516631156]

- Lee TK, Wickrama KAS, O’Neal CW. Health continuity over mid-later years in enduring marriages: Economic pressure as couple- and individual-level mediator. J Soc Pers Relat. 2020; 37(2):377-92. [DOI:10.1177/0265407519865971]

- Wong CW, Kwok CS, Narain A, Gulati M, Mihalidou AS, Wu P, et al. Marital status and risk of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2018; 104(23):1937-48. [DOI:10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313005] [PMID]

- Pahlavanzadeh F, Taghi Yar, Zahra, Refahi, Jaleh. [The study of the effectiveness of conflict resolution skills on willingness and desire to marry and its dimensions in single girls (Persian)]. Women Family Stud. 2019; 45(12):29-43. [Link]

- Rajabi G, Khandade A. Effect of premarital education based on idealistic marital expectation’s on reducing idealistic marital expectation’s in marriage applicant couples: A single case study. Psychol Methods Models. 2021; 12(43):14-30. [Link]

- Rajabi G, Abbasi G, Sodani M, Aslani K. [The effectiveness of premarital education program based on premarital interpersonal choices and knowledge in bachelor students (Persian)]. J Fam Couns Psychother. 2017; 6(1):79-97. [Link]

- Rafiee A, Etemadi O, Bahrami F, Jazayeri R. [The effect of preparration education for marrriage on marital expectations of the under contract girls in Isfahan city (Persian)]. J Woman Soc. 2015; 6(21):21-40. [Link]

- Bostani Khalesi Z. Sexual health needs of education in pre-marriage couples: Explaining, development and Validation of the tool and design of an educational program (Persian) PhD dissertation]. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences; 2016.

- Mazloomi Mahmodabad S, Eslami H, Dehghani Zadeh M, Arabi M. [Survey the effect of pre-marriage counseling on knowledge and attitudes couple in Yazd (Persian)]. Tolooebehdasht. 2016; 15 (2):105-13. [Link]

- Hazavehei MM, Shirahmadi S, Roshanaei Gh, Kazemzade M, Majzubi MM. [Educational program status of premarital counseling centers in Hamadan Province based on theory of reasoned action (TRA) (Persian)]. J Fasa Univ Med Sci. 2013; 3(3):241-7. [Link]

- Iran Statistical Centre. The report on the social and cultural situation of Iran. Tehran: Iran Statistical Center; 2021. [Link]

- Abedi B, Fatehizade M. [Preparing for marriage: A practical guide for young people, parents and family professionals (Persian)]. Tehran: Kankash; 2016. [Link]

- Rostami M, Ghezelseflo M. [Examining the effects of the SYMBIS pre- marriage training on engaged couples’ communication beliefs (Persian)]. Iran J Fam Psychol. 2018; 5(1):45-56. [DOI:10.22034/ijfp.2018.245538]

- Murniati C, Pujihasvuty R, Nasution SL, Oktriyanto, Amrullah H. Marriage readiness of adolescents aged 20-24 in Indonesia. J BiomPopul. 2024; 13(1):1-11. [DOI:10.20473/jbk.v13i1.2024.1-11]

- Khojasteh Mehr R, Daniali Z, Shirali Nia K. Married students’ experiences regarding marriage readiness. Iran J Fam Psychol. 2021; 2(2):39-50. [Link]

- Azimi Khoei A, Zahrakar K, Ahmady Kh. [The effectiveness of premarital education based on the prevention and relationship enhancement program (PREP) on communication beliefs and attitudes toward marriage of couples on the verge of marriage (Persian)]. J IslamLifeStyle Cent Health. 2021; 63-73. [Link]

- Poley JM. A Pre-marriage Proposal: Getting ready for marriage, an Adlerian design [MA thesis]. Adlerian Counseling and Psychotherapy; 2011. [Link]

- Ningrum DNF, Latifah M, Krisnatuti D. Marital readiness: Exploring the key factors among university students. Hum Indones Psychol J. 2021; 18(1):65-74. [DOI:10.26555/humanitas.v18i1.17912]

- Bestooh H. [Evaluation of factor structure of Criteria Readiness for Marriage Questionnaire (CMRQ) and its relationship with risky Behaviors on single students of Shahid Chamran university of Ahvaz (Persian)] [MA thesis]. Ahvaz: Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz; 2016. [Link]

- Carroll JS, Badger S, Willoughby BJ, Nelson LJ, Madsen SD, McNamara Barry C. Ready or Not?:Criteria for marriage readiness among emerging adults. J Adolesc Res. 2009; 24(3):349-75. [DOI:10.1177/0743558409334253]

- Karunia NE, Rahaju S. Marriage Readiness of Emerging Adulthood. Jurnal Ilmu Pendidikan Psikologi Bimbingan dan Konseling. 2019; 9(1):29-34. [DOI:10.24127/gdn.v8i2.1338]

- Ismail Z, Ahmad Diah NAA. Relationship between financial well-being, self-esteem and readiness for marriage among final year students in Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM). Malays J Soc Sci Hum. 2020; 5(6):19-24. [DOI:10.47405/mjssh.v5i6.425]

- Misbach IH, Rahman S, Damaianti LF. Does identity status influence marriage readiness among early adults in Bandung City? Paper presented at: 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences. 2017 , Bandung, Indonesia. [DOI:10.5220/0007041603860391]

- Mousavi SF, Gholinasab Ghoje Beigloo R. [The role of emotional support and self-determination in prediction of marital conflicts among married women (Persian)]. J Woman Fam Stud. 2019; 7(1):51-71. [DOI:10.22051/jwfs.2019.18873.1655]

- Ghalili Ranani Z. [Study and compilation of local criteria for marriage readiness from the perspective of youth, parents and marriage experts, and evaluation of marriage readiness in the youth of Isfahan (Persian)] [PhD dissertation]. Isfahan: University of Isfahan; 2013. [Link]

- Stinnette N. Readiness for marital competence and family, dating, and personality factors. J Home Econ. 1969; 61:686-3. [Link]

- Fathi Ashtiani A, Ahmadi Kh. [Investigating the limiting factors and barriers in student marriage (Persian)]. J Psychol. 2000; 3(2):133-21. [Link]

- Lacey RS, Reifman A, Scott JP, Harris SM, Fitzpatrick J. Sexual-moral attitudes, love styles, and mate selection. J Sex Res. 2004; 41(2):121-8. [DOI:10.1080/00224490409552220] [PMID]

- Carroll JS, Willoughby B, Badger S, Nelson LJ, McNamara Barry C, Madsen SD. So close, yet so far away: The impact of varying marital horizons on emerging adulthood. J Adolesc Res. 2007; 22(3):219-47. [DOI:10.1177/0743558407299697 ]

- Gholamaliee B, Jamoorpour S, Sori A, Soheilizad M, Khazaei S, Noryian F, et al. [Criteria of marriage in married couples referred to Tuyserkan marriage counseling center in 2015 (Persian)]. Pajouhan Sci J. 2015; 14(4):38-47. [DOI:10.21859/psj-140438]

- Osarenren N, Makinde B, Jonathan A. Relationship between perception of marriage and readiness to mary among final year undergraduate students of University of Lagos, Nigeria. J Educ Rev. 2012; 5(4). [Link]

- Larson JH, Thayne TR. Marital attitudes and personal readiness for marriage of young adult children of alcoholics. Alcohol Treat Q. 1998; 16(4):59-73. [DOI:10.1300/J020v16n04_06]

- Rahmah N, Kurniawati W. Relationship between marriage readiness and pregnancy planning among prospective brides. J Public Health Res. 2021; 10(s1):jphr.2021.405. [DOI:10.4081/jphr.2021.2405] [PMID]

- Satari E, Akbari Kamrani M, Farid M. Necessity for redesigning premarital counseling classes based on marriage readiness from the perspective of adolescents and specialists: A need assessment based on the Bourich model and quadrant analysis. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2019; 34(1). [DOI:10.1515/ijamh-2019-0042] [PMID]

- Goldscheider FK, Waite LJ. Sex differences in the entry into marriage. Am J Sociol. 1986; 92(1):91-109. [DOI:10.1086/228464]

- Oppenheimer VK. A theory of marriage timing. Am J Sociol. 1988; 93(4):563--91. [DOI:10.1086/229030]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2023/07/15 | Accepted: 2025/04/30 | Published: 2026/01/11

Received: 2023/07/15 | Accepted: 2025/04/30 | Published: 2026/01/11

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |