Thu, Jan 29, 2026

Volume 33, Issue 4 (9-2023)

JHNM 2023, 33(4): 239-249 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rouhi F, Asiri S, Bakhshi F, Kazemnezhad leili E. Factors Related to Feelings of Loneliness and Attitudes Toward Ageing in Retired Older Adults. JHNM 2023; 33 (4) :239-249

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2192-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2192-en.html

1- Nursing (MSN), School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2- Assistant Professor, Department of community health, school of Nursing andMidwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran ,shahlaasiri@gums.ac.ir

3- Assistant professor, social determinants of health research center, School of health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

4- Associate Professor, Biostatistics, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Assistant Professor, Department of community health, school of Nursing andMidwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran ,

3- Assistant professor, social determinants of health research center, School of health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

4- Associate Professor, Biostatistics, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 510 kb]

(801 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1384 Views)

Full-Text: (716 Views)

Introduction

Aging is a normal stage of life caused by improved living standards, health, social and economic conditions, reduced mortality, and increased life expectancy. According to the 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) report, about 612 million people of the world’s population were older people, and it is predicted that this number will reach 1.2 billion people in 2025 and 2 billion people in 2050 [1]. According to 2015 Iran’s population survey statistics, the number of older people (7450000 people) is expected to make up 30% of the population in 2050 [2]. The average proportion of the elderly population in Iran is 9.28%, where Guilan Province ranks first with 13.25%, of which 11.45% are for urban areas and 16.35% for rural areas. In general, surveys indicate the rapid growth of the elderly population in Iran, so it is predicted that in 2026, the number of older people in the country will reach 21.8% of the total population [3, 4]. The change in the demographic structure of the population has a profound effect on the economic and social dimensions of the countries, and its consequences have an impact on almost all parts of society and the lives of older people [5].

Loneliness is an unpleasant and negative personal experience that causes boredom, worthlessness, despair, anxiety, and depression. Loneliness does not necessarily mean living alone. Rather it means feeling alone in a crowd [6]. Surveys have shown that 20%-40% of older people feel alone [4], and 5%-7% have reported feelings of constant or severe loneliness. Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity and disturbed sleep. These people experience a sense of emptiness, sadness, and estrangement, which affects their social interactions, lifestyle, and health differently. Loneliness is associated with decreased cognitive function and participation in social activities, especially in people with chronic diseases. Loneliness is an important indicator of the mental health and quality of life (QoL) in older people, which increases the occurrence of mental and physical diseases in them [5]. Vakili et al. showed that older people feel lonelier, and the factors of education, marital status, gender, and place of residence play an effective role in loneliness [7]. Different people have different attitudes toward aging. The attitude of older people towards aging can affect the experience of aging and adaptation to the aging process [8]. Suppose some people have a negative attitude toward aging while reaching old age, and these negative attitudes are continued. In that case, they may experience negative effects on their physical and mental health, which can affect their QoL [9]. The attitude towards aging is different in men and women and is directly related to the cultural stereotypes common in society. Women have less control over their aging conditions, and this feeling is seen in them every so often [10, 11].

Considering the importance of loneliness and attitudes towards aging and the effect of these two variables on the mental health and QoL of older people, determination of the feeling of loneliness, attitude towards aging, and factors related to it in the elderly can help the nurses to create a positive attitude and rational acceptance of the changes caused by aging in older people, and improve their relationships with each other and with themselves, reduce their feeling of loneliness, and finally enhance their physical and mental health.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive-analytical study with a cross-sectional design was conducted from February to June 2020 on older people covered by the National Pension Fund in Rasht City, north of Iran. The sample size was determined at a 95% confidence interval and considering a test power of 90% and a correlation coefficient of r=0.366 between the attitude towards aging and loneliness based on the results of Manookian et al. [12]. In this study, 18 variables were included as related factors. Considering 10 samples for each variable and 10% sample dropout, the final sample size was determined to be 237. The proportional stratified sampling method was used for sampling. The inclusion criteria were age ≥60 years, membership in the centers covered by the National Pension Fund of Rasht City, the ability to communicate verbally, and willingness to participate in the study. Samples with incomplete and distorted questionnaires were excluded from the study. Data collection was done using a demographic checklist for surveying age, gender, level of education, monthly income, place of residence, occupation after retirement, marital status, number of children, living arrangement, history of any disorders and chronic diseases, history of hospitalization in the last two years, history of traumatic event experience in the last 2 years, smoking, alcohol consumption, use of neuropsychiatric drugs, interaction with others, and participation in social activities. Also, the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults-short version (SELSA-S) and attitudes to aging questionnaire (AAQ).

The SELSA-S includes 3 subscales of social, family, and emotional loneliness. The score of emotional loneliness can be obtained by summing up the scores of the 2 latter subscales. This questionnaire has 15 items, which is reduced to 14 in its Persian version. The items are scored from completely agree (1 point) to completely disagree (5 points). Its total score ranges from 14 to 70. All items, except items 14 and 15, are scored in reverse, and a higher score indicates a greater feeling of loneliness [13]. The Persian version of this questionnaire was validated by Jowkar and Salimi [14]. Using the Cronbach α, the reliability of the whole questionnaire was obtained at 0.930; for the emotional loneliness subscale, 0.88; for the social loneliness subscale, 0.831; and for the family loneliness subscale, 0.723.

The AAQ has three dimensions: Physical change, psychological growth, and psychosocial loss. The items are scored from completely agree (1 point) to completely disagree (5 points). The items for psychosocial loss are scored in reverse. Its total score ranges from 24 to 120. High scores in physical change and psychological growth show a more positive attitude, while higher scores in the dimension of psychosocial loss show a negative attitude towards aging [15]. The Persian version of this tool was validated by Rejeh et al. [16]. In the present study, the reliability of the whole questionnaire using the Cronbach α was obtained at 0.905; for the physical change subscale, it was 0.807; for psychological growth subscale, 0.744; and for the psychosocial loss subscale, 0.821.

To collect data, after receiving the letter of introduction from the university, the researcher went to the Pension Fund of Rasht City, and after providing sufficient explanations and obtaining informed consent from the participants, 240 questionnaires were completed by them, of which 5 were excluded due to being incomplete. Data analysis was done in SPSS software, version 21 using descriptive statistics and the Spearman correlation test, the Mann-Whitney U test, the Friedman test, and the Kruskal-Wallis test (due to the non-normality of data distribution). To measure the relationship between the feeling of loneliness and the attitude towards aging, after adjusting the effects of intervening sociodemographic factors, the multiple linear regression analysis (backward method) was used. The significance level was set at P=0.05.

Results

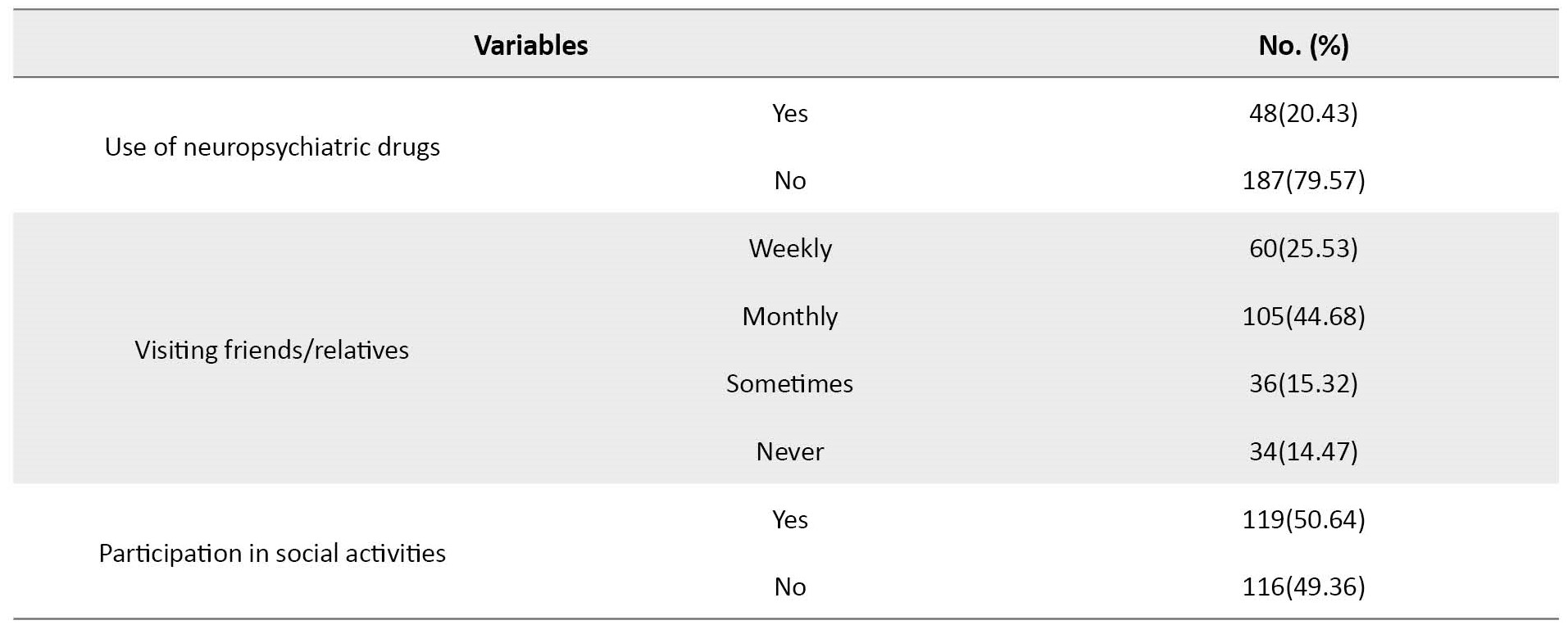

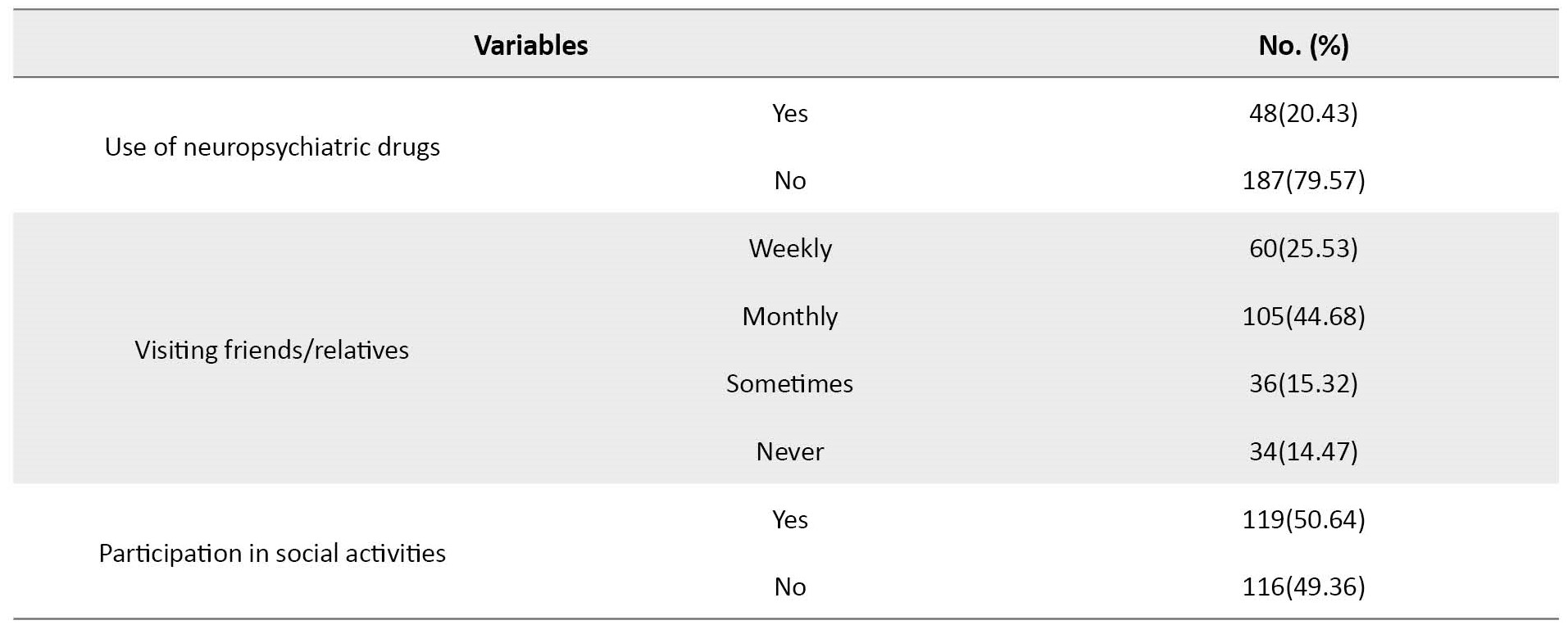

Participants were 235 older people; most (52.3%) were in the age range of 60-64 years, male (53.6%), married (93.2%), with a high school diploma (51.1%), and had ≥3 children (51.9%). The monthly income of most of them (87.2%) was adequate, and they were living in urban areas (92.3%). More than 80% of them had no occupation after retirement. In terms of living arrangements, 54.5% were living with their spouses. Moreover, 35.7%, 18.3%, and about 32% had disorders and chronic diseases, a history of hospitalization in the past two years, and experienced serious financial problems or other crises, respectively. Furthermore, 20.4% used tobacco, 3.4% used alcohol, and 20.4% used neuropsychiatric drugs. Most were visiting friends or relatives on a monthly basis (44.7%), while about 15% had no contact with friends or relatives. Almost 51% of them had social activity (Table 1).

Their Mean±SD SELSA-S score was 27.7±0.6, whose data had abnormal distribution based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results. The Mean±SD scores of SELSA-S subscales, including social loneliness, romantic loneliness, emotional loneliness, and family loneliness, were 1.89±0.61, 1.87±0.67, 1.84±0.52, and 1.81±0.52, respectively. According to the Friedman test results, there was no statistically significant difference between them. The Mean±SD total score of AAQ was 81.1±7.3. The mean scores of AAQ subscales, including psychological growth, physical change, and psychosocial loss, were 31.6±3.2, 28.8±4.3, and 20.8±4.1, respectively. According to the Friedman test results, there was a statistically significant difference between them (P=0.001).

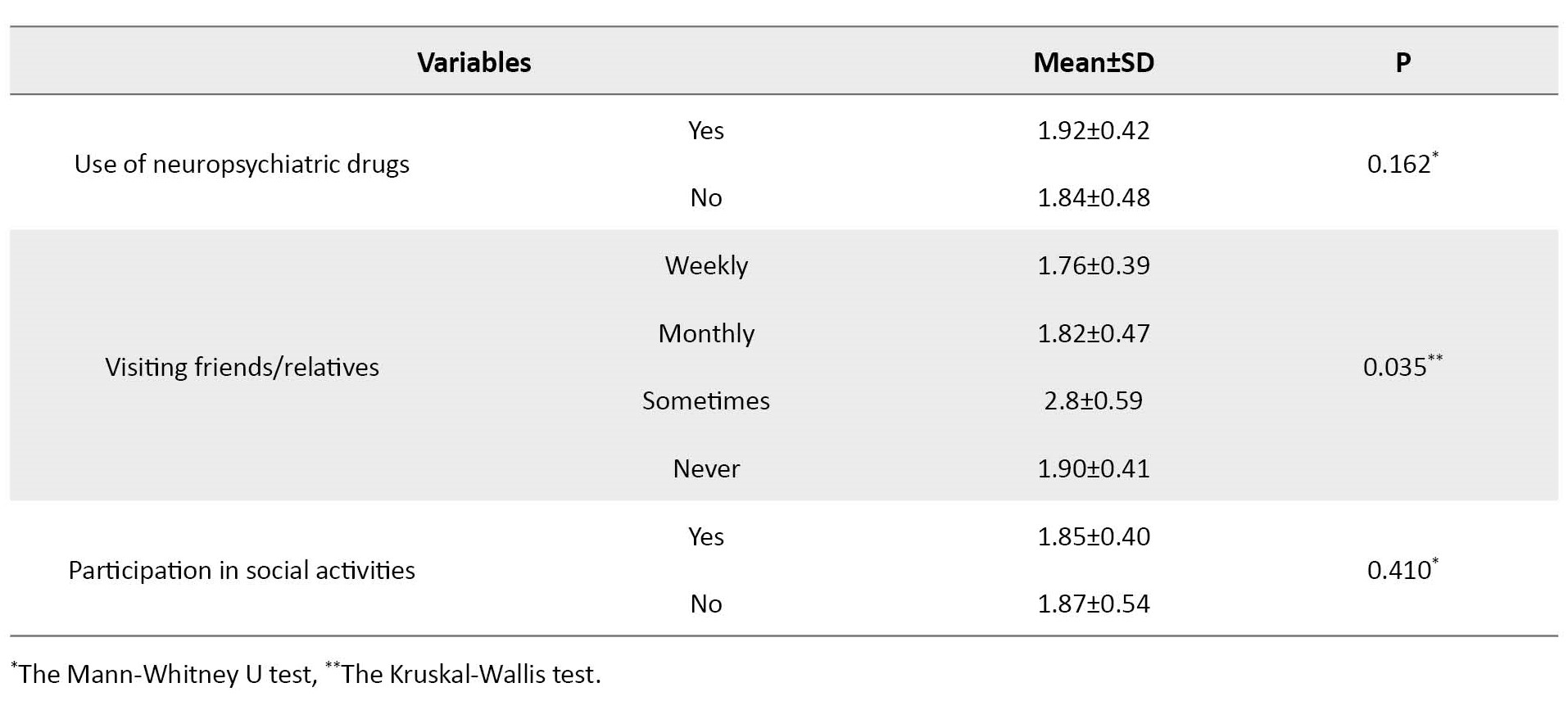

Loneliness had a statistically significant relationship with education (P=0.004), monthly income (P=0.017), and interaction with others (P=0.035) that was shown in Table 2.

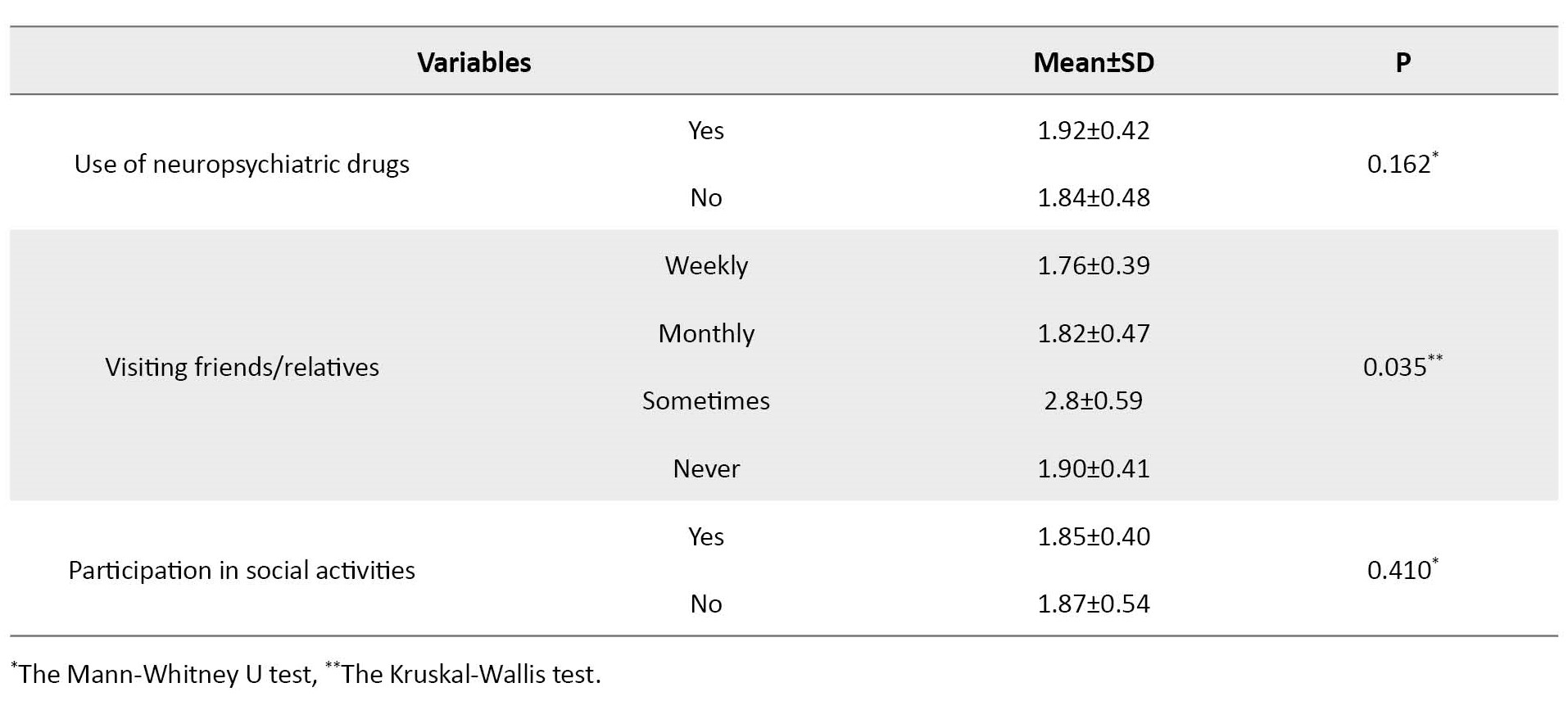

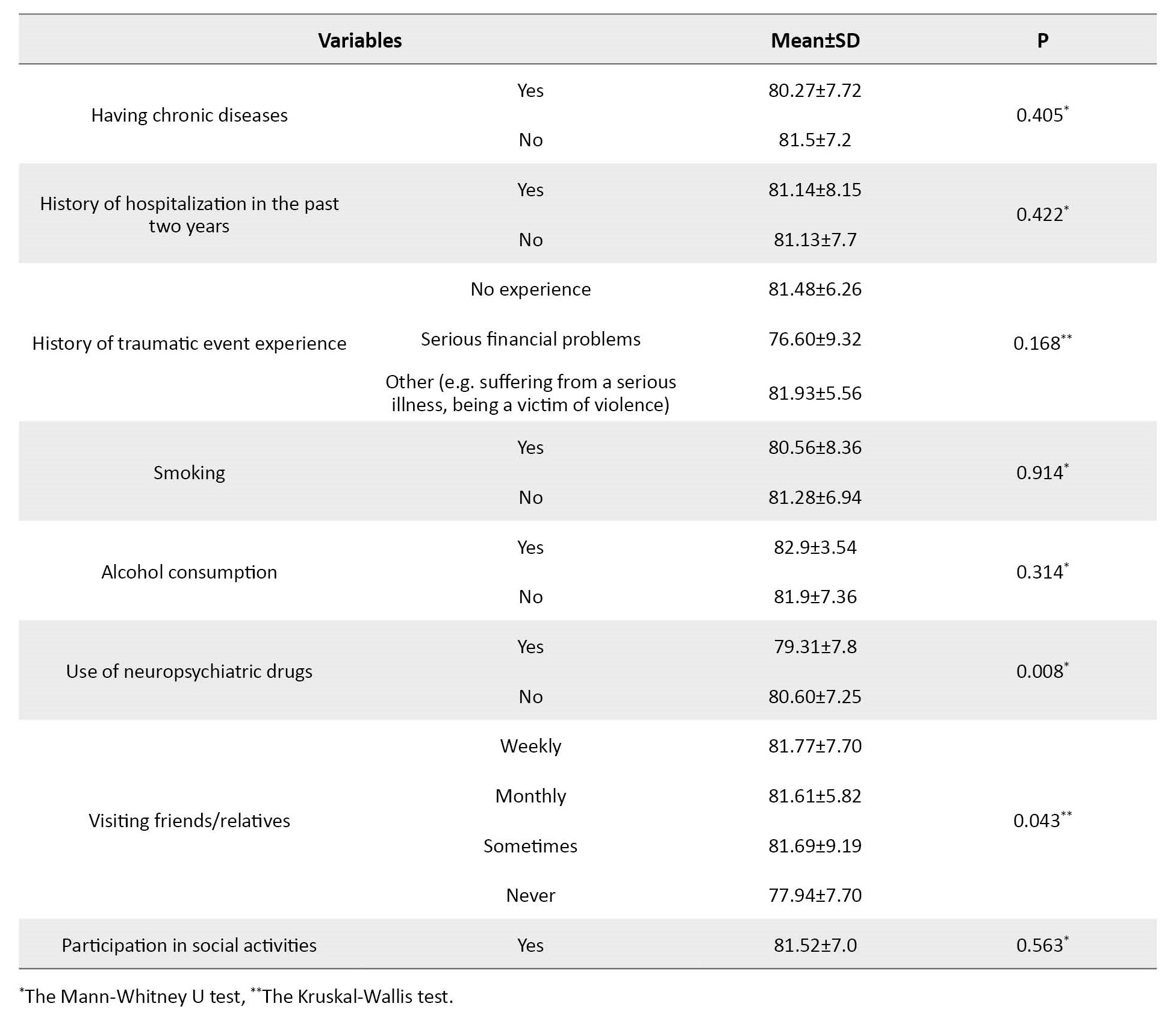

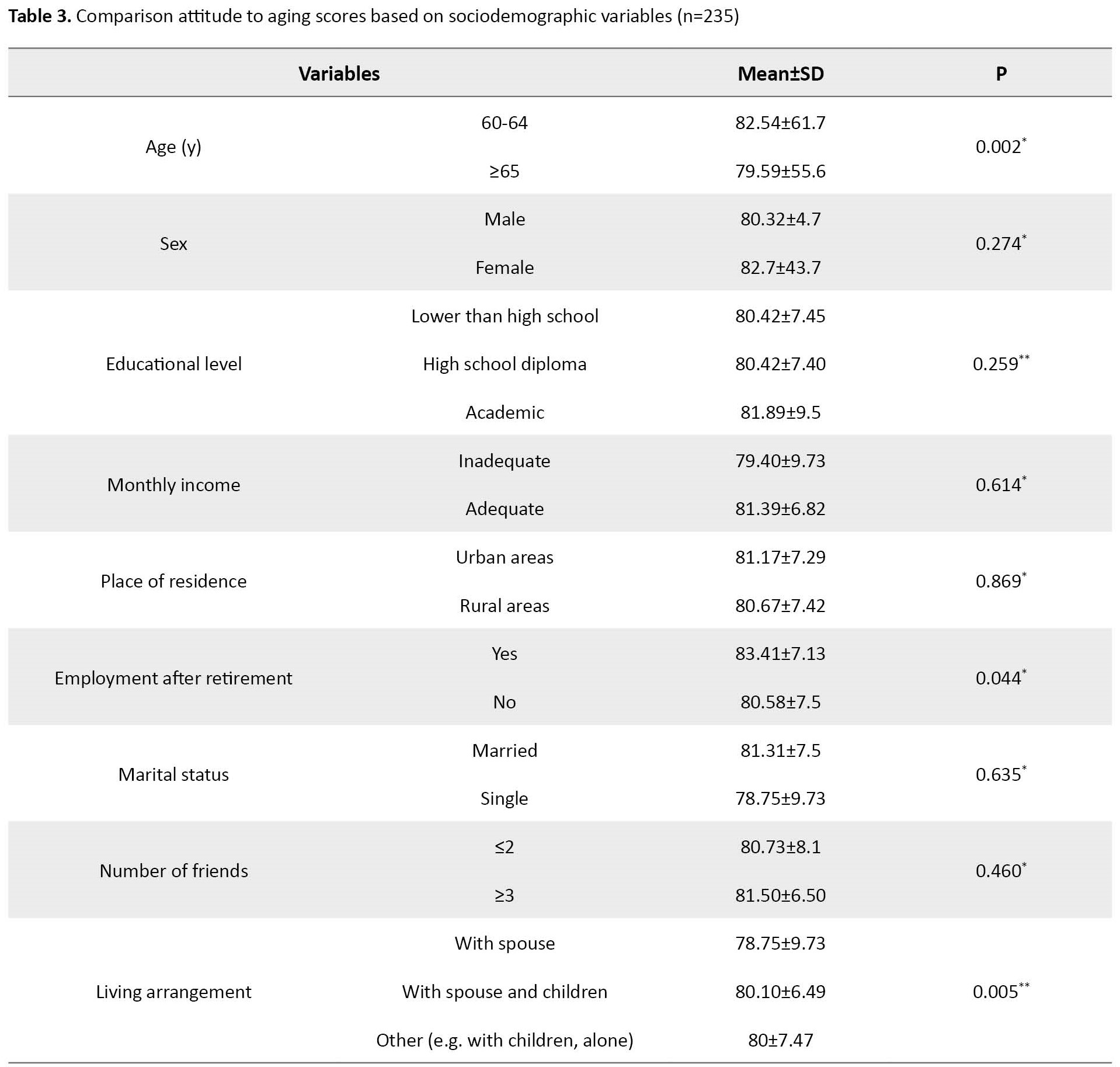

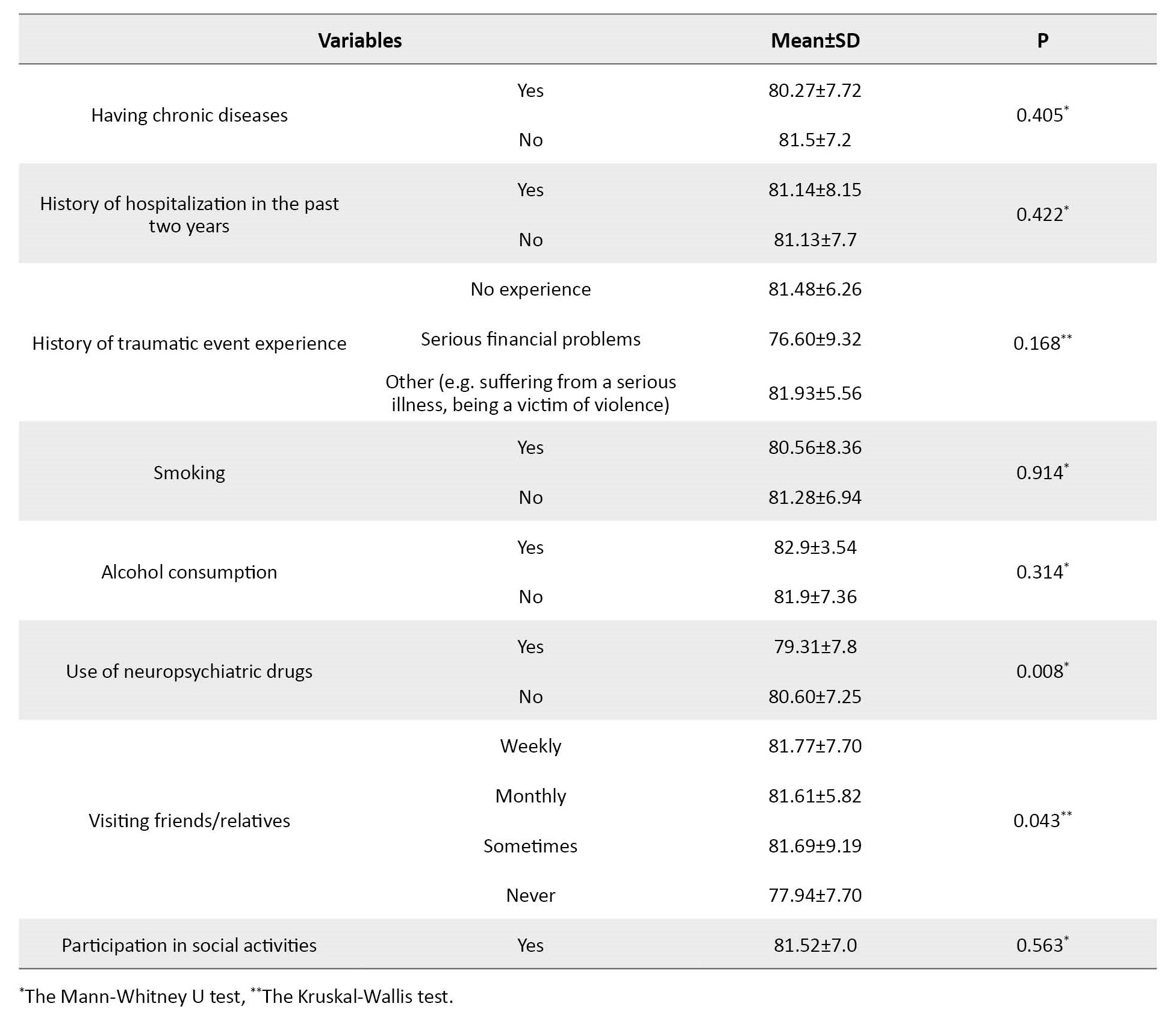

Attitude towards aging had a statistically significant relationship with age (P=0.002), employment after retirement (P=0.044), living arrangements (P=0.005), taking neuropsychiatric drugs (P=0.008), and interaction with others (P=0.043) that was shown in Table 3.

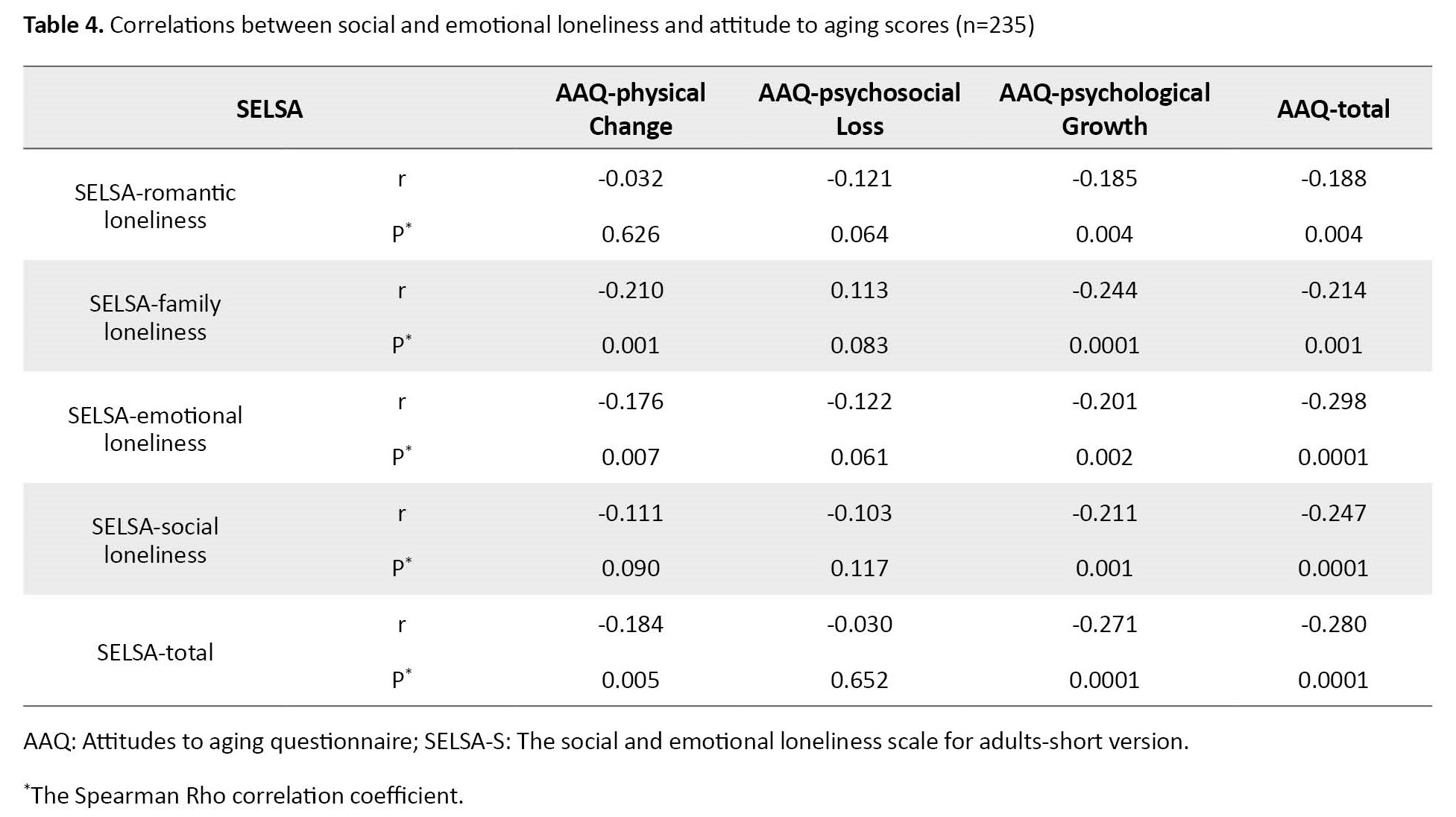

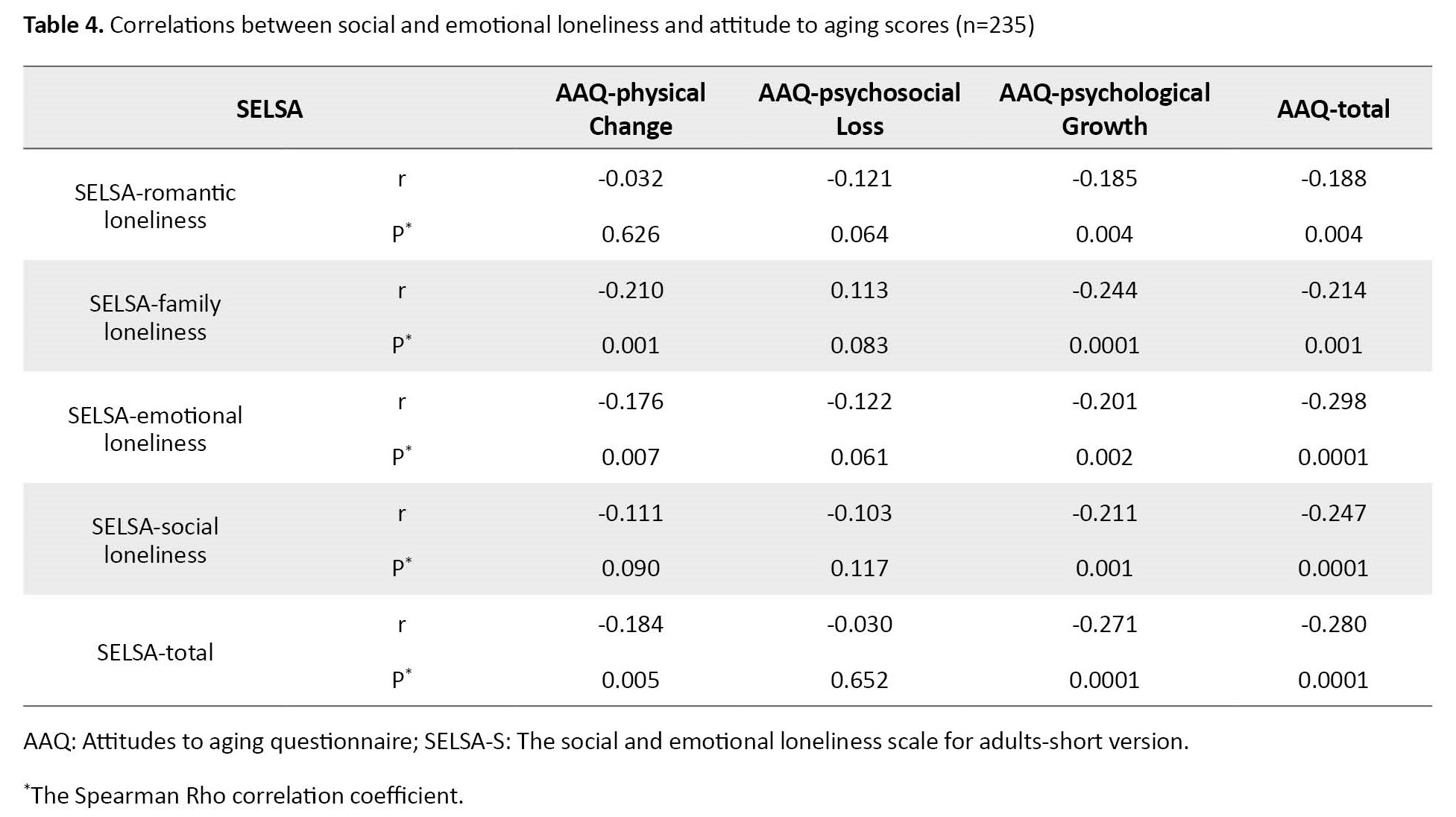

According to the Spearman test, the score of SELSA-S had a significant negative correlation with the scores of physical change and psychosocial loss subscales of AAQ and the total AAQ score (r=-0.184, P=0.005; r=-0.271, P=0.001; r=-0.180, P=0.001). Also, AAQ score had a significant negative correlation with all domains of SELSA-S, including romantic loneliness (r=-0.188, P=0.004) and family loneliness (r=-0.298, P=0.001). emotional loneliness (r=-0.247, P=0.001) and social loneliness (r=-0.214, P=0.001) that was shown in Table 4.

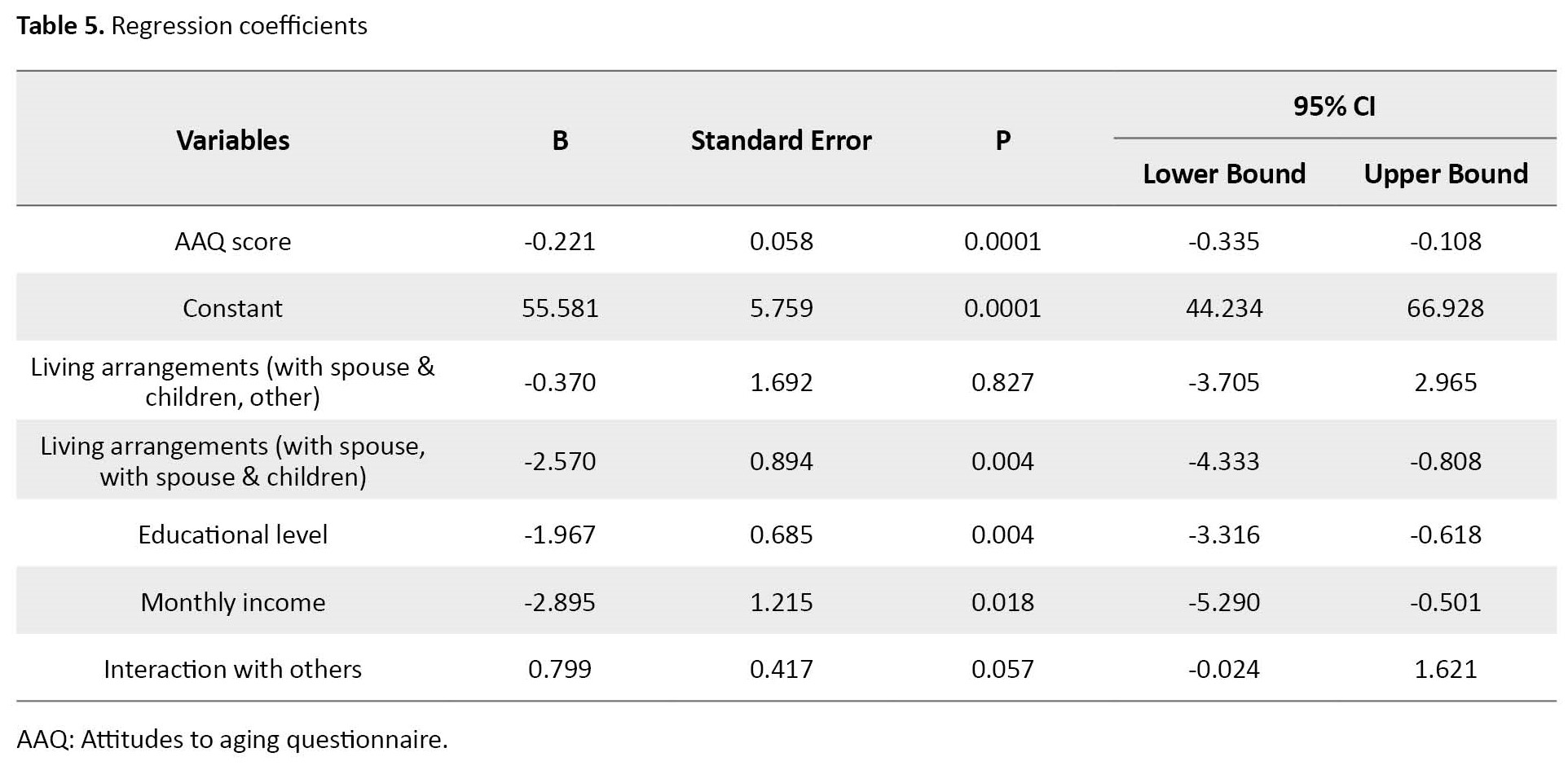

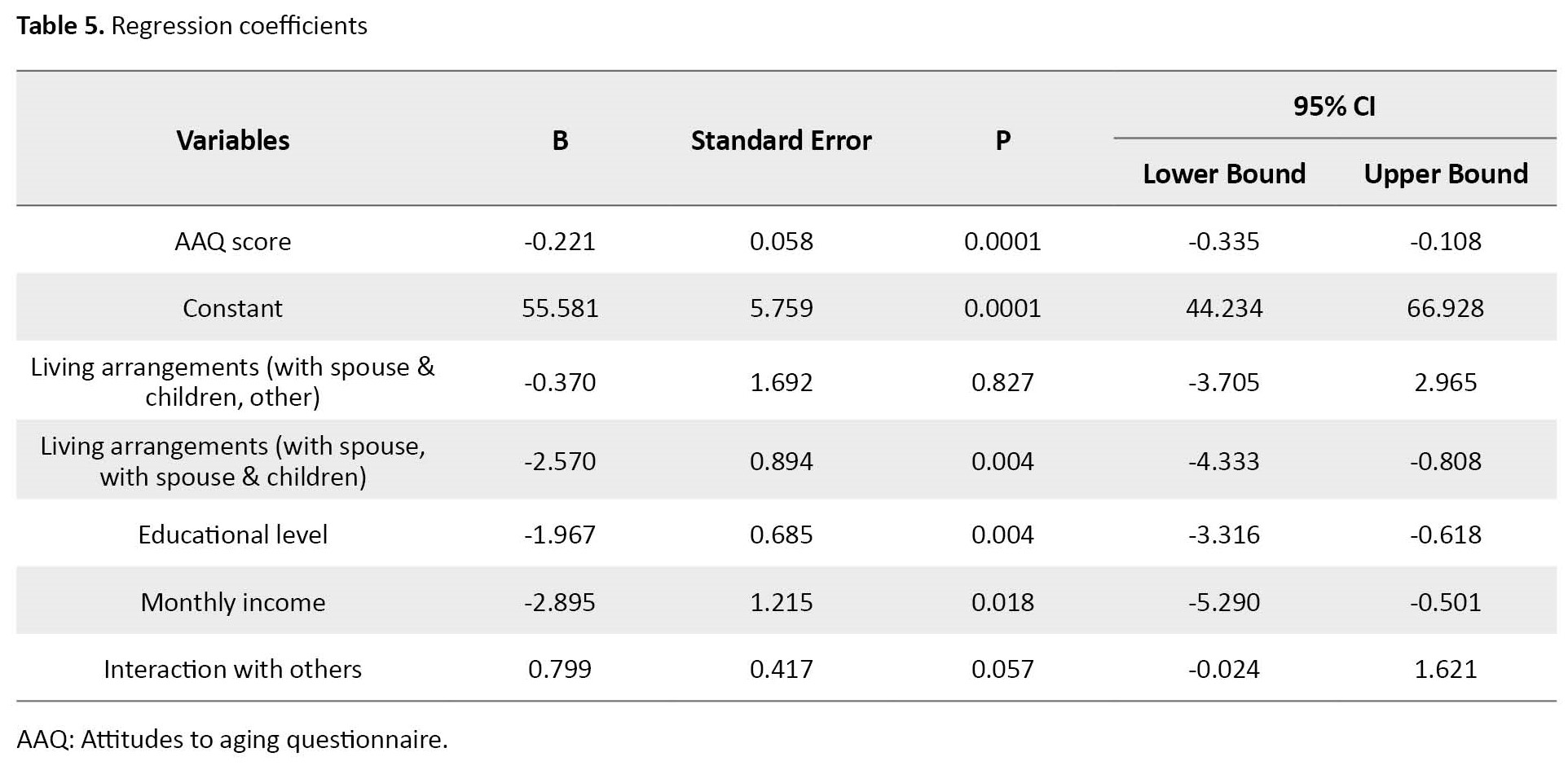

All the sociodemographic variables with a significant relationship with loneliness and attitude scores were entered into the model for multiple regression analysis. Finally, after controlling these variables, the attitude was a predictor of loneliness; with the increase in attitude towards aging, loneliness decreases (B=-0.22, 95% CI, -0.33% to -0.108%, P=0.0001). Older people who lived with their spouses had a lower loneliness score than the elderly who lived with their spouses and children (B=-2.57, 95% CI, -4.333% to -0.808%, P=0.001). With the increase in education level (B=-1.96, 95% CI, -3.31% to -0.61%, P=0.004) and monthly income (B=0.80, 95% CI, -0.02% to -1.62%, P=0.018), the score of loneliness decreased. Moreover, the loneliness score increased with the lack of interaction with friends/relatives (B=0.799, 95% CI, -0.02% to 1.62%, P=0.050) (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study’s findings showed that older people in Rasht had a very low feeling of loneliness. This finding is not consistent with the results of some studies in Iran [17], Canada [18], and Indonesia [19] that reported a high level of loneliness, while is consistent with the results of some studies in Turkey [20] and Iran [21]. A study in Taiwan also reported a low level of loneliness in older people [22]. In old age, variables such as relationships with children and other family members, losses, and retirement play an important role in feeling lonely. Socially isolated people are not necessarily lonely and vice versa. How lonely a person feels depends partly on their own and their culture’s expectations of relationships [23]. Therefore, our findings regarding no significant difference among older people in terms of loneliness domains can be due to not controlling the effect of such variables in the present study.

The results of this study showed that older people’s attitudes towards aging were higher than the average level, where the score of psychological growth was higher, followed by the scores of physical change and psychosocial loss domains. This finding is consistent with the results of the studies conducted by Cadmus et al. [24] and Korkmaz et al. [20], who reported an above-average attitude towards aging, while Momeni et al. showed that the attitude towards aging in older people was lower than average [25]. This discrepancy in results can be due to individual, social, cultural, and environmental differences.

The present study showed that educational level, monthly income and interaction with others had a significant relationship with the loneliness of the elderly such that with the increase in the level of education and income, their feeling of loneliness decreased and with the lack of interactions with friends/relatives, their loneliness feelings increased. These findings are consistent with some studies in Iran [26 , 27] and Europe [28]. Most studies have reported that the feeling of loneliness is also related to the female gender [18, 19, 26] and age [20, 27].

The present study showed that age, employment after retirement, living arrangements, use of neuropsychiatric drugs, and interaction with others had a significant relationship with the attitude of older people toward aging. The attitude score was higher in older people aged 60-64, with employment after retirement, living with a spouse and children, not using neuropsychiatric drugs and those who visited others weekly, monthly, or on occasion. A study conducted in the Czech Republic showed that education and living arrangements were the most important predictors of attitudes toward aging [29]. Also, a study in Taiwan indicated that age, living arrangement, and income level of older people were the factors related to their attitude towards aging [30]. Our results are consistent with their results. The role of factors such as educational level and physical ability in predicting the attitude toward aging was reported in Kisvetrová’s study [31], but they were not reported in our study. The study of Kalfoss [32] in Norway also showed that gender, health status, education, and marital status were important predictors of attitude toward aging. In our study, some limitations, such as the basis for answering questions and the existence of other hidden and interfering factors, have made some of these sociodemographic variables ineffective and insignificant.

The present study showed a relationship between loneliness with the attitude toward aging in older people and the role of some sociodemographic factors in predicting them. Continuous monitoring of older people and their situations, such as reduced social interactions, understanding the attitudes and beliefs of older people, and increasing the awareness of health care workers, including nurses, to know the factors that affect the health of older people, their families and people around them are recommended. It is also recommended to design educational and therapeutic programs to prevent the feeling of loneliness in older people and create a positive attitude towards aging in them.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR. GUMS.REC.1398.432). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and they were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This study was extracted from the master's thesis of Fahime Rouhi approved by the Department of Nursing, Guilan University of Medical Sciences and the study was financially supported by the Guilan University of Medical Science.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design and final approval: All authors; Data analysis: Ehsan Kazemnezhad Leili; Preparing the initial draft: Shahla Asiri and Fahimeh Roohi; Supervision: Shahla Asiri.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research at Guilan University of Medical Sciences for the financial support and all the seniors who participated in the study for their cooperation.

References

Aging is a normal stage of life caused by improved living standards, health, social and economic conditions, reduced mortality, and increased life expectancy. According to the 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) report, about 612 million people of the world’s population were older people, and it is predicted that this number will reach 1.2 billion people in 2025 and 2 billion people in 2050 [1]. According to 2015 Iran’s population survey statistics, the number of older people (7450000 people) is expected to make up 30% of the population in 2050 [2]. The average proportion of the elderly population in Iran is 9.28%, where Guilan Province ranks first with 13.25%, of which 11.45% are for urban areas and 16.35% for rural areas. In general, surveys indicate the rapid growth of the elderly population in Iran, so it is predicted that in 2026, the number of older people in the country will reach 21.8% of the total population [3, 4]. The change in the demographic structure of the population has a profound effect on the economic and social dimensions of the countries, and its consequences have an impact on almost all parts of society and the lives of older people [5].

Loneliness is an unpleasant and negative personal experience that causes boredom, worthlessness, despair, anxiety, and depression. Loneliness does not necessarily mean living alone. Rather it means feeling alone in a crowd [6]. Surveys have shown that 20%-40% of older people feel alone [4], and 5%-7% have reported feelings of constant or severe loneliness. Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity and disturbed sleep. These people experience a sense of emptiness, sadness, and estrangement, which affects their social interactions, lifestyle, and health differently. Loneliness is associated with decreased cognitive function and participation in social activities, especially in people with chronic diseases. Loneliness is an important indicator of the mental health and quality of life (QoL) in older people, which increases the occurrence of mental and physical diseases in them [5]. Vakili et al. showed that older people feel lonelier, and the factors of education, marital status, gender, and place of residence play an effective role in loneliness [7]. Different people have different attitudes toward aging. The attitude of older people towards aging can affect the experience of aging and adaptation to the aging process [8]. Suppose some people have a negative attitude toward aging while reaching old age, and these negative attitudes are continued. In that case, they may experience negative effects on their physical and mental health, which can affect their QoL [9]. The attitude towards aging is different in men and women and is directly related to the cultural stereotypes common in society. Women have less control over their aging conditions, and this feeling is seen in them every so often [10, 11].

Considering the importance of loneliness and attitudes towards aging and the effect of these two variables on the mental health and QoL of older people, determination of the feeling of loneliness, attitude towards aging, and factors related to it in the elderly can help the nurses to create a positive attitude and rational acceptance of the changes caused by aging in older people, and improve their relationships with each other and with themselves, reduce their feeling of loneliness, and finally enhance their physical and mental health.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive-analytical study with a cross-sectional design was conducted from February to June 2020 on older people covered by the National Pension Fund in Rasht City, north of Iran. The sample size was determined at a 95% confidence interval and considering a test power of 90% and a correlation coefficient of r=0.366 between the attitude towards aging and loneliness based on the results of Manookian et al. [12]. In this study, 18 variables were included as related factors. Considering 10 samples for each variable and 10% sample dropout, the final sample size was determined to be 237. The proportional stratified sampling method was used for sampling. The inclusion criteria were age ≥60 years, membership in the centers covered by the National Pension Fund of Rasht City, the ability to communicate verbally, and willingness to participate in the study. Samples with incomplete and distorted questionnaires were excluded from the study. Data collection was done using a demographic checklist for surveying age, gender, level of education, monthly income, place of residence, occupation after retirement, marital status, number of children, living arrangement, history of any disorders and chronic diseases, history of hospitalization in the last two years, history of traumatic event experience in the last 2 years, smoking, alcohol consumption, use of neuropsychiatric drugs, interaction with others, and participation in social activities. Also, the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults-short version (SELSA-S) and attitudes to aging questionnaire (AAQ).

The SELSA-S includes 3 subscales of social, family, and emotional loneliness. The score of emotional loneliness can be obtained by summing up the scores of the 2 latter subscales. This questionnaire has 15 items, which is reduced to 14 in its Persian version. The items are scored from completely agree (1 point) to completely disagree (5 points). Its total score ranges from 14 to 70. All items, except items 14 and 15, are scored in reverse, and a higher score indicates a greater feeling of loneliness [13]. The Persian version of this questionnaire was validated by Jowkar and Salimi [14]. Using the Cronbach α, the reliability of the whole questionnaire was obtained at 0.930; for the emotional loneliness subscale, 0.88; for the social loneliness subscale, 0.831; and for the family loneliness subscale, 0.723.

The AAQ has three dimensions: Physical change, psychological growth, and psychosocial loss. The items are scored from completely agree (1 point) to completely disagree (5 points). The items for psychosocial loss are scored in reverse. Its total score ranges from 24 to 120. High scores in physical change and psychological growth show a more positive attitude, while higher scores in the dimension of psychosocial loss show a negative attitude towards aging [15]. The Persian version of this tool was validated by Rejeh et al. [16]. In the present study, the reliability of the whole questionnaire using the Cronbach α was obtained at 0.905; for the physical change subscale, it was 0.807; for psychological growth subscale, 0.744; and for the psychosocial loss subscale, 0.821.

To collect data, after receiving the letter of introduction from the university, the researcher went to the Pension Fund of Rasht City, and after providing sufficient explanations and obtaining informed consent from the participants, 240 questionnaires were completed by them, of which 5 were excluded due to being incomplete. Data analysis was done in SPSS software, version 21 using descriptive statistics and the Spearman correlation test, the Mann-Whitney U test, the Friedman test, and the Kruskal-Wallis test (due to the non-normality of data distribution). To measure the relationship between the feeling of loneliness and the attitude towards aging, after adjusting the effects of intervening sociodemographic factors, the multiple linear regression analysis (backward method) was used. The significance level was set at P=0.05.

Results

Participants were 235 older people; most (52.3%) were in the age range of 60-64 years, male (53.6%), married (93.2%), with a high school diploma (51.1%), and had ≥3 children (51.9%). The monthly income of most of them (87.2%) was adequate, and they were living in urban areas (92.3%). More than 80% of them had no occupation after retirement. In terms of living arrangements, 54.5% were living with their spouses. Moreover, 35.7%, 18.3%, and about 32% had disorders and chronic diseases, a history of hospitalization in the past two years, and experienced serious financial problems or other crises, respectively. Furthermore, 20.4% used tobacco, 3.4% used alcohol, and 20.4% used neuropsychiatric drugs. Most were visiting friends or relatives on a monthly basis (44.7%), while about 15% had no contact with friends or relatives. Almost 51% of them had social activity (Table 1).

Their Mean±SD SELSA-S score was 27.7±0.6, whose data had abnormal distribution based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results. The Mean±SD scores of SELSA-S subscales, including social loneliness, romantic loneliness, emotional loneliness, and family loneliness, were 1.89±0.61, 1.87±0.67, 1.84±0.52, and 1.81±0.52, respectively. According to the Friedman test results, there was no statistically significant difference between them. The Mean±SD total score of AAQ was 81.1±7.3. The mean scores of AAQ subscales, including psychological growth, physical change, and psychosocial loss, were 31.6±3.2, 28.8±4.3, and 20.8±4.1, respectively. According to the Friedman test results, there was a statistically significant difference between them (P=0.001).

Loneliness had a statistically significant relationship with education (P=0.004), monthly income (P=0.017), and interaction with others (P=0.035) that was shown in Table 2.

Attitude towards aging had a statistically significant relationship with age (P=0.002), employment after retirement (P=0.044), living arrangements (P=0.005), taking neuropsychiatric drugs (P=0.008), and interaction with others (P=0.043) that was shown in Table 3.

According to the Spearman test, the score of SELSA-S had a significant negative correlation with the scores of physical change and psychosocial loss subscales of AAQ and the total AAQ score (r=-0.184, P=0.005; r=-0.271, P=0.001; r=-0.180, P=0.001). Also, AAQ score had a significant negative correlation with all domains of SELSA-S, including romantic loneliness (r=-0.188, P=0.004) and family loneliness (r=-0.298, P=0.001). emotional loneliness (r=-0.247, P=0.001) and social loneliness (r=-0.214, P=0.001) that was shown in Table 4.

All the sociodemographic variables with a significant relationship with loneliness and attitude scores were entered into the model for multiple regression analysis. Finally, after controlling these variables, the attitude was a predictor of loneliness; with the increase in attitude towards aging, loneliness decreases (B=-0.22, 95% CI, -0.33% to -0.108%, P=0.0001). Older people who lived with their spouses had a lower loneliness score than the elderly who lived with their spouses and children (B=-2.57, 95% CI, -4.333% to -0.808%, P=0.001). With the increase in education level (B=-1.96, 95% CI, -3.31% to -0.61%, P=0.004) and monthly income (B=0.80, 95% CI, -0.02% to -1.62%, P=0.018), the score of loneliness decreased. Moreover, the loneliness score increased with the lack of interaction with friends/relatives (B=0.799, 95% CI, -0.02% to 1.62%, P=0.050) (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study’s findings showed that older people in Rasht had a very low feeling of loneliness. This finding is not consistent with the results of some studies in Iran [17], Canada [18], and Indonesia [19] that reported a high level of loneliness, while is consistent with the results of some studies in Turkey [20] and Iran [21]. A study in Taiwan also reported a low level of loneliness in older people [22]. In old age, variables such as relationships with children and other family members, losses, and retirement play an important role in feeling lonely. Socially isolated people are not necessarily lonely and vice versa. How lonely a person feels depends partly on their own and their culture’s expectations of relationships [23]. Therefore, our findings regarding no significant difference among older people in terms of loneliness domains can be due to not controlling the effect of such variables in the present study.

The results of this study showed that older people’s attitudes towards aging were higher than the average level, where the score of psychological growth was higher, followed by the scores of physical change and psychosocial loss domains. This finding is consistent with the results of the studies conducted by Cadmus et al. [24] and Korkmaz et al. [20], who reported an above-average attitude towards aging, while Momeni et al. showed that the attitude towards aging in older people was lower than average [25]. This discrepancy in results can be due to individual, social, cultural, and environmental differences.

The present study showed that educational level, monthly income and interaction with others had a significant relationship with the loneliness of the elderly such that with the increase in the level of education and income, their feeling of loneliness decreased and with the lack of interactions with friends/relatives, their loneliness feelings increased. These findings are consistent with some studies in Iran [26 , 27] and Europe [28]. Most studies have reported that the feeling of loneliness is also related to the female gender [18, 19, 26] and age [20, 27].

The present study showed that age, employment after retirement, living arrangements, use of neuropsychiatric drugs, and interaction with others had a significant relationship with the attitude of older people toward aging. The attitude score was higher in older people aged 60-64, with employment after retirement, living with a spouse and children, not using neuropsychiatric drugs and those who visited others weekly, monthly, or on occasion. A study conducted in the Czech Republic showed that education and living arrangements were the most important predictors of attitudes toward aging [29]. Also, a study in Taiwan indicated that age, living arrangement, and income level of older people were the factors related to their attitude towards aging [30]. Our results are consistent with their results. The role of factors such as educational level and physical ability in predicting the attitude toward aging was reported in Kisvetrová’s study [31], but they were not reported in our study. The study of Kalfoss [32] in Norway also showed that gender, health status, education, and marital status were important predictors of attitude toward aging. In our study, some limitations, such as the basis for answering questions and the existence of other hidden and interfering factors, have made some of these sociodemographic variables ineffective and insignificant.

The present study showed a relationship between loneliness with the attitude toward aging in older people and the role of some sociodemographic factors in predicting them. Continuous monitoring of older people and their situations, such as reduced social interactions, understanding the attitudes and beliefs of older people, and increasing the awareness of health care workers, including nurses, to know the factors that affect the health of older people, their families and people around them are recommended. It is also recommended to design educational and therapeutic programs to prevent the feeling of loneliness in older people and create a positive attitude towards aging in them.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR. GUMS.REC.1398.432). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and they were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This study was extracted from the master's thesis of Fahime Rouhi approved by the Department of Nursing, Guilan University of Medical Sciences and the study was financially supported by the Guilan University of Medical Science.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design and final approval: All authors; Data analysis: Ehsan Kazemnezhad Leili; Preparing the initial draft: Shahla Asiri and Fahimeh Roohi; Supervision: Shahla Asiri.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research at Guilan University of Medical Sciences for the financial support and all the seniors who participated in the study for their cooperation.

References

- World Health Organisation. Aging and health. Geneva: WHO; 2022. [Link]

- Statistical center of Iran. [National population and housing census Iran statistics center (Persian)]. Tehran: Statistical center of Iran; 2017. [Link]

- Madani Ghahfarokhi S. [Report on the situation of aging in Iran (Persian)]. Tehran: Saba Pension Strategies Institute; 2022. [Link]

- Statistical center of Iran. [Population forecasting, National portal of statistics, data and information (Persian)]. Tehran: Statistical center of Iran; 2020. [Link]

- Safarkhanlou H, Rezaei Ghahroodi Z. [The evolution of the elderly population in Iran and the world (Persian)]. Stat J. 2017; 5(3):8-16. [Link]

- Kalantari A, Hoseynizadeharani SS. [City and social relationships: A study of the relationship between social isolation and level of received social support with the experience of loneliness (case study: Tehran residents) (Persian)]. Urban Stud. 2015; 5(16):87-118. [Link]

- Vakili M, Mirzaei M, Modarresi M. Loneliness and its related factors among elderly people in Yazd. Elderly Health J. 2017; 3(1):10-5. [Link]

- Kuru Alici N, Kalanlar B. Attitudes towards aging and loneliness among older adults: A mixed methods study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021; 57(4):1838-45. [DOI:10.1111/ppc.12757] [PMID]

- Hosseiny RS, Alijanpour Agha Maleki M, Etemadifar S, Rafiei H. [Religious attitudes and spiritual health among elderly inpatient adults in Shahrekord hospitals (Persian)]. Jorjani Biomed J. 2016; 4(1):56-65. [Link]

- Moradi A, Shariatmadari A. [The comparison between death anxiety and loneliness among the elderly with optimistic and pessimistic life orientation (Persian)]. Aging Psychol. 2016; 2(2):133-41. [Link]

- Sagan O. The loneliness of personality disorder: A phenomenological study. Ment Health Soc Incl. 2017; 21 (4):213-21. [DOI:10.1108/MHSI-04-2017-0020]

- Manookian A, Navab E, Zomorodi M. [The relationship between self-compassion and attitude to ageing in middle aged people (Persian)]. Iran J Nurs Res. 2020; 15(5):20-8. [Link]

- Di Tommosso E, Brannen C, Best LA. Measurment and validity charactristices of the short version of the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults. Educ Psychol Meas. 2004; 64(1):99-119. [DOI:10.1177/0013164403258450]

- Jowkar B, Salimi A. [Pyschometricpropertices of the short form of the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults (Persian)]. J Behav Sci. 2012; 5(4):311 -7. [Link]

- Laidlaw K, Power MJ, Schmidt S; WHOQOL-OLD Group. The Attitude to Aging Questionaire (AAQ): Development and psychometric properties. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007; 22(4):367-79. [DOI:10.1002/gps.1683] [PMID]

- Rejeh N, HeraviKarimooi M, Foroughan M, Azam B. [The Persian version of Attitudes to Ageing Questionnaire (AQQ): A validation study (Persian)]. Payesh. 2016; 15(5):567-78. [Link]

- Salehi tilaki E, Ilali E, Taraghi Z, Mousavinasab N. [The comparative of loneliness and its related factors in rural and urban elderly people in Behshahr city (Persian)]. J Gerontol. 2019; 4 (1):52-61 [DOI:10.29252/joge.3.4.6]

- Savage RD, Wu W, Li J, Lawson A, Bronskill SE, Chamberlain SA, et al. loneliness among older adults in the community during covid-19: A cross sectional survey in Canada. BMJ Open. 2021; 11(4):e044517. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044517] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Susanty S, Chung MH, Chiu HY, Chi MJ, Hu SH, Kuo CL, et al. Prevalence of the lonliness and associated factors among community-dwelling older adults in Indonesia: A cross-sectional study.Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4911. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19084911] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Korkmaz Aslan G, Kartal A, Özen Çınar İ, Koştu N. The relationship between attitudes toward aging and health-promoting behaviours in older adults. Int J Nurs Pract. 2017; 23(6):e12594. [DOI:10.1111/ijn.12594] [PMID]

- Yousefzadeh P, Bastini F, Haghani H, Hosseini RS. [Loneliness and the contributing factors in the elderly patients with type 2 diabetes: A descriptive cross- sectional study (Persian)]. Iran J Nurs. 2021; 33(128):27-39. [Link]

- Huang PH, Chi MJ, Kuo CL, Wu SV, Chuang YH. Prevalence of loneliness and related factors among older adults in Taiwan: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey. Inquiry. 2021; 58:469580211035745. [DOI:10.1177/00469580211035745] [PMID] [PMCID]

- World Health Organisation. Social isolation and loneliness among older people: Advocacy brief. Geneva: WHO: 2021. [Link]

- Cadmus EO, Adebusoye LA, Owoaje ET. Attitude towards ageing and perceived health status of community-dwelling older persons in a low resource setting: A rural-urban comparison. BMC Geriatr. 2021; 21(1):454. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-021-02394-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Momeni K, Karami J, Rafiee Z. Comparison of death anxiety, self-concept and attitudes to old age in the elderly living on their own, residing in nursing homes full-time or part-time, or living with extended families in Kermanshah, Iran. Res Bull Med Sci. 2018; 23(1):e5. [Link]

- Motamedi N, Shafiei-Darabi SM, Amini Z. [Social and emotional loneliness among the elderly, and its association with social factors affecting health in Isfahan City, Iran, in years 2017-2018 (Persian)]. J Isfahan Med Sch, 2018 ; 36(486):750-6. [DOI:10.22122/JIMS.V36I486.10104]

- Motamedi A, Qaderi Bagajan K, Mazaheri Nejad Fard G, Soltani S. [Comparative study of feeling lonely between retired and labor elderly men (Persian)]. Q J Soc Work. 2017; 6(2):43-50. [Link]

- Guthmuller S. Loneliness among older adults and in Europe: The relative importance of early and later life conditions. Plos One. 2022; 17(5):e0267562. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0267562] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kisvetrová H, Mandysová P, Tomanová J, Steven A. Dignity and attitudes to aging: A cross-sectional study of older adults. Nurs Ethics. 2022; 29(2):413-24. [DOI:10.1177/09697330211057223] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lee SH, Yeh CJ, Yang CY, Wang CY, Lee MC. Factors associated with attitude to aging among Taiwanese middle-age and older adults: Based on population-representative national data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2654. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19052654] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kisvetrová H, Herzig R, Bretšnajdrová M, Tomanová J, Langová K, Školoudík D. Predictors of quality of life and attitude to ageing in older adults with and without dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2021; 25(3):535-42. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2019.1705758] [PMID]

- Kalfoss M. Gender differences in attitudes to ageing among norwegian older adults. Open J Nurs. 2016; 6(03):255-66. [DOI:10.4236/ojn.2016.63026]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2023/06/28 | Accepted: 2023/06/29 | Published: 2023/06/29

Received: 2023/06/28 | Accepted: 2023/06/29 | Published: 2023/06/29

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |