Sat, Dec 6, 2025

Volume 33, Issue 3 (6-2023)

JHNM 2023, 33(3): 203-213 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Naghizadeh S, Robatjazi M, Abbasi M, Mohammadi A. Midwives' Views on Virginity Testing: A Cross-sectional Study. JHNM 2023; 33 (3) :203-213

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2186-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2186-en.html

1- Ph.D Candidate of Reproductive Health, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, Nursing and Midwifery School, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Assistant Professor, Department of Midwifery, Islamic Azad University Pishva-Varamin Branch, Tehran, Iran

3- Associate Professor, Medical Ethics and Law Research Center, Department of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Assistant Professor, Department of Midwifery, Islamic Azad University Pishva-Varamin Branch, Tehran, Iran

3- Associate Professor, Medical Ethics and Law Research Center, Department of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 476 kb]

(1050 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1154 Views)

Full-Text: (716 Views)

Introduction

Virginity testing is defined as an act and process of inspecting the genitals of unmarried girls and women to determine if they have had vaginal intercourse [1]. The primary purpose of this examination is sexual abstinence, delaying sexual intercourse until marriage, and preventing the spread of sexually transmitted diseases and AIDS in various cultures [2]. This examination is often performed in African and Asian countries. The growing number of virginity testing and repair applicants in European countries, including the Netherlands, Sweden, Spain, and Canada, without previous experience with such examinations indicates its globalization and the dominant role of cultural beliefs in accepting the test [3, 4, 5].

However, most societies accept virginity as an undeniable value [6]. Virginity testing without medical indication is questionable due to the double standard and violence against women [7]. The prevalence of virginity testing at personal request in some countries has become a matter of life and death due to virginity’s connection to the dignity of families and its consequences, such as notoriety, suicide, and honor killing [8, 9]. It has been criticized by human rights organizations [10]. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations special rapporteur have banned virginity testing as a form of inhumane, cruel, degrading, and sexual violence against women. However, this practice continues in many countries, including Iran [11]. Olson et al., in a review study, concluded that virginity testing is not only not good but also will cause physical, mental, and psychological damage to the person being examined [12].

On the other hand, according to the evidence in countries where the hymen is the virginity index, such examinations cause people to have oral sex, anal sex, and genital contact, which is often unprotected and leads to sexually transmitted diseases [13, 14].

However, planning and adopting appropriate policies related to virginity testing as a sociocultural product in any country requires studying. There are no clear instructions regarding virginity testing at the personal request of applicants and medical staff members involved in this examination and the country’s medical centers [11].

What seems to be important is that this examination is not done to protect or promote girls’ health and is, in fact, a violation of the patient’s rights because this examination is often performed without the person’s informed consent. The examination result without the person’s consent will be told to others, contrary to the principle of patient confidentiality. There may be issues following this announcement that the health system cannot respond to it [14, 15]. As a member of the virginity testing team, the midwife has professional ethical duties, such as showing respect to the person regarding the examination, preventing psychological injuries, physical and social, protecting individual rights, ensuring legal authorization for all steps, the confidentiality of personal information, understanding the patient’s feelings and, if necessary, act as a supporter for the person [16]. It is important that midwives, as individuals involved in this examination, must be aware of the relevant laws in this field to carry out their professional responsibilities and the resulting moral responsibilities [17]. In our country, Iran, midwives face many requests for examination of hymen and virginity membranes annually, but unfortunately, university education does not answer the questions that will arise for this group. Midwives may face many cultural, social, legal, psychological, and moral challenges in relation to performing or not performing this examination. Therefore, the present study investigated midwives’ views on virginity testing.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 210 midwives working in private offices, hospitals, health centers, and hospitals affiliated with Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz City, Iran, from January to August 2020. The inclusion criteria included midwives living in Tabriz working in one of the health centers, private clinics, or universities who were willing to participate in the study.

The sample size for this study was based on the results of the study of Zeyneloglu et al. [18]. Considering P=0.65, d=10% around p, and α=0.05, the sample size was 207 people, and the sample size was 210.

The researcher had to take samples from comprehensive health centers or private clinics; the sampling method in this study was different. Due to the small number of midwives working in universities, these midwives were selected by convenience sampling method; for midwives working in offices, health centers, and hospitals, a simple random method was used. First, the list of midwifery clinics, health centers, and hospitals in Tabriz was determined and then numbered in the order in which the samples were selected randomly. Also, according to the number of midwives working in each center, the sample was randomly selected using www.Random.org based on the number assigned to each.

Due to the lack of a standard questionnaire in this field, a researcher-made questionnaire was designed based on the questionnaires used by Robatjazi et al. [8], Gursoy and Vural [17], Zeyneloglu et al. [18], and Simbar et al. [19]. This questionnaire consists of two main parts.

The first part of the questionnaire was the sociodemographic characteristics, including age, work experience, marital status, occupation, place of work, education, ethnicity, religion, place of residence, and family financial status. Some questions include, “Have you ever been tested for virginity yourself?” “Do you have a single son, brother, daughter, or sister?” and “how much virginity testing have you done so far?”

The second part of the questionnaire had 55 questions (6 dimensions), emotions of the examined people (6 questions about the feelings of the examinees), consequences of virginity testing (11 questions), reasons for midwives’ desire to do or not to do virginity testing (11 questions), common causes of virginity testing (9 questions), the appropriate approach to virginity testing (7 questions), and respecting the rights of examinees (11 questions). This questionnaire was scored based on the 5-point Likert scale (totally agree, agree, no opinion, disagree, and totally disagree) with a total score of 55 to 275. Questions 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27, 28, and 48 are scored in reverse.

The validity of the questionnaire was assessed using face and content validity by emailing 10 experts, including members of the faculty of midwifery and reproductive health of the country’s medical universities, obstetricians, and forensic specialists. The Content Validity Index (CVI) and the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) were calculated according to the Lawshe table [20]. CVI and CVR were 0.86 and 0.82, respectively. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed by retesting for two weeks on 20 employed midwives. The internal correlation coefficient using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for the questions was calculated at 0.82.

The study data were gathered by referring to private clinics, health centers, and university centers, and comprehensive information on the reasons for conducting the research, benefits, results, confidentiality of data, and how to conduct the research was provided. To comply with the ethical aspects, participation in the study was voluntary, and they were assured that all information would remain confidential with the researcher. Participants could withdraw from the study at any stage. Also, we did not record the participants’ identities to protect privacy.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software, version 21. Descriptive statistics and the Pearson test, independent t-test, and one-way ANOVA were used to analyze data. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in this study are given in Table 1.

.jpg)

.jpg)

In examining the various dimensions of “emotions of the examined person on virginity testing,” most participants (more than 60%) agreed and totally agreed with considering the emotion of the examinees in virginity testing.

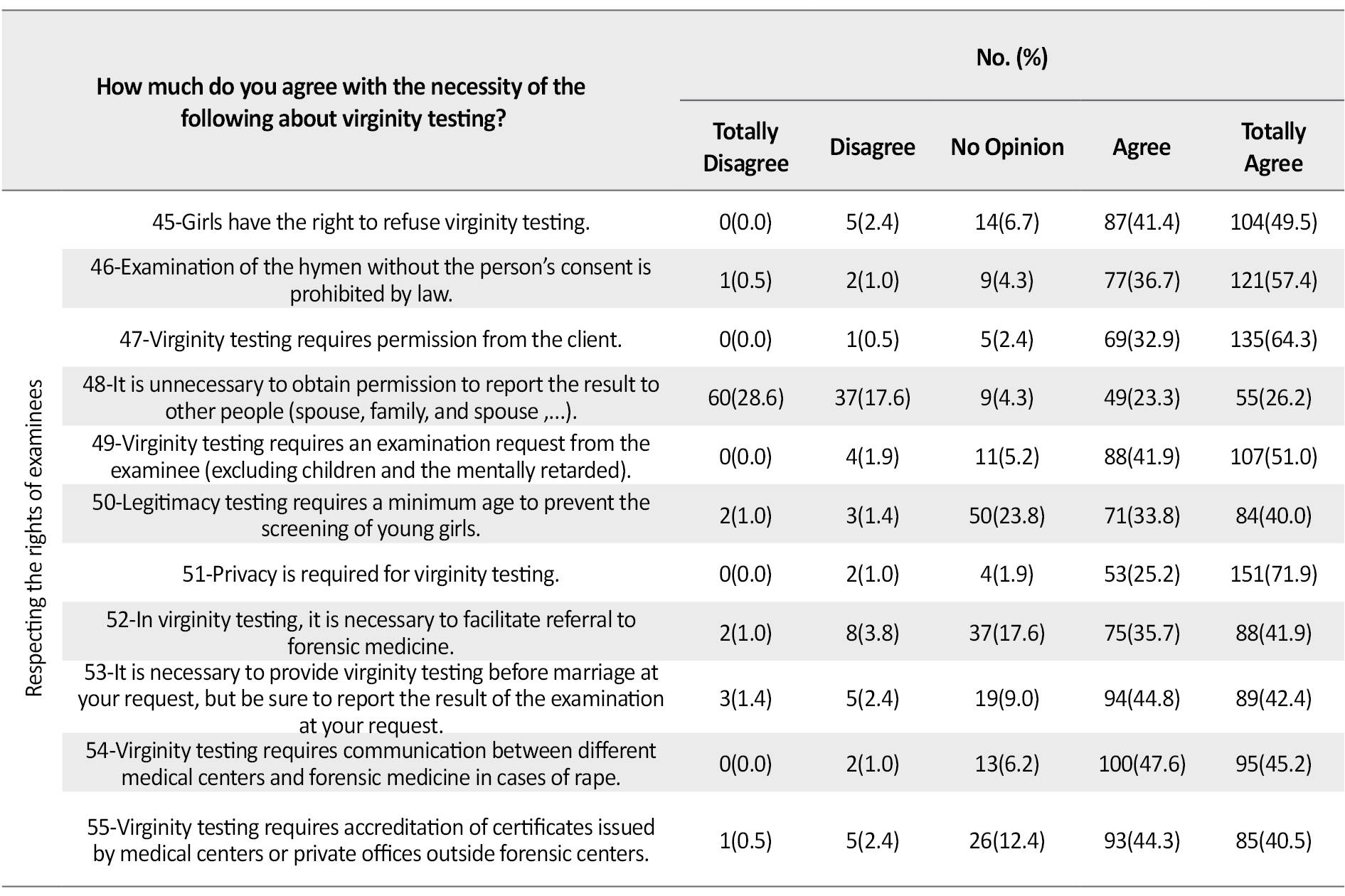

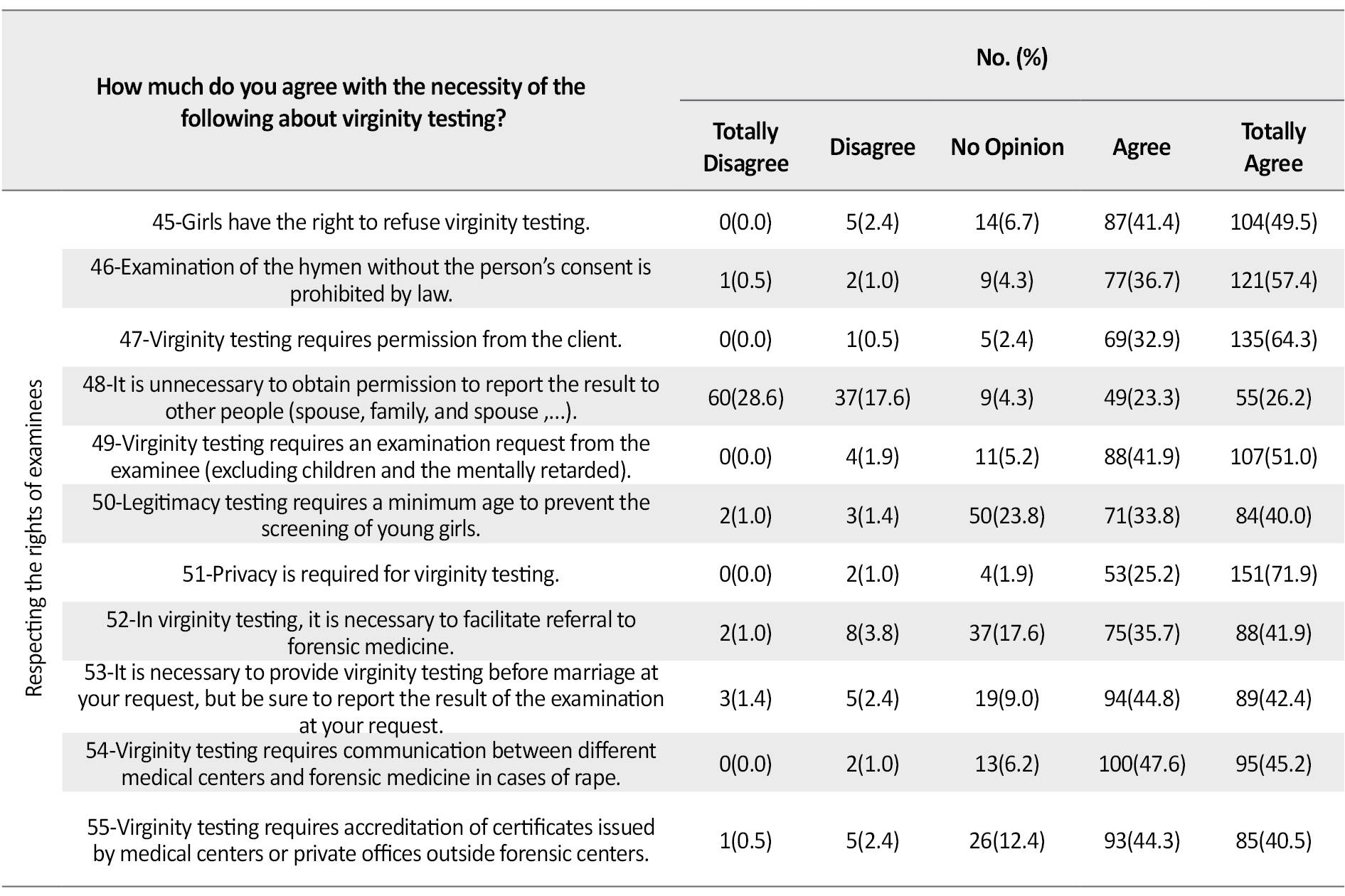

In examining the various dimensions of “emotions of the examined person on virginity testing,” most participants (more than 60%) agreed and totally agreed with considering the emotion of the examinees in virginity testing. Regarding the “consequences of virginity examination” dimensions questions, 40% agreed and totally agreed with the adverse consequences of virginity testing. Regarding the “reasons for midwives’ desire to do or not to do virginity testing,” 56.2% believed that “examining the virginity veil has no therapeutic value or even prevention of the problem and should not be done.” Regarding the “common causes of virginity testing” dimension, in the study of rape and sexual abuse, 29.5% strongly agreed; most midwives believed that one of the most common causes of virginity testing was to investigate rape and sexual abuse. Regarding the dimension of the “appropriate approach to virginity testing,” 45.5% strongly agreed, and 0.5% had opposite option about the question “awareness of examiners, especially midwives, about the cultural, social and legal consequences of virginity testing is important and necessary” (Table 2).

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Mean±SD of the overall score of the midwives’ view on virginity testing was 206.98±16.58 out of the score range of 159-258 (Table 3).

.jpg)

The variables of age (P=0.033), education level (P=0.001), place of residence (P=0.001), and place of employment (P=0.001) had a statistically significant difference with the overall score of midwives` views towards the virginity testing. Also, there was a statistically significant difference between the emotions of the examined person with the place of residence (P=0.001), place of employment (P=0.013), and the number of examinations performed by midwives (P=0.022). The reasons for midwivesʹ desire to do or not to do, was significant based on ethnicity (P=0.018) and place of employment (P=0.003). The variables of the place of employment (P=0.011) and personal history of virginity examination (P=0.001) were significate with the common causes of virginity testing and the variables of education level (P=0.001) and place of residence (P=0.001) with the dimension of the appropriate approach to virginity testing. Finally the variables of age (P=0.001), an education level (P=0.001), place of residence (P=0.028) work history (P=0.002), place of employment (P=0.002) and the number of virginity testing (P=0.022) with respecting the rights of examinees were statistically significant (Table 4).

.jpg)

Discussion

The present study’s findings indicate that most midwives agreed on “paying attention to the feelings of the examinees about the virginity testing.” This study showed that most participants believed that virginity testing caused physical and psychological pain and a kind of invasion of privacy in the examinee. This is consistent with a statement issued by a group of Denmark forensic experts [21] that considered pain, mental health problems, and disregard for the patient’s rights as the effects of virginity testing.

Most participants believed that virginity testing exacerbates feelings of gender inequality, increases physical and verbal violence, and decreases self-esteem. In a similar study, midwives believed virginity screening and hymen repair were patriarchal elements used to control violence against women [22]. Our result is consistent with them. Most midwives in our study believed that “virginity testing has no therapeutic or even preventive value and should not be done.” In Simbar et al.’s study, the most important reasons for virginity testing were professional performance and economic motivation [19]. Meanwhile, in our research, few midwives performed virginity testing for economic motivation. This difference can be attributed to the different cultural bases of the two studies. Gursoy’s study showed that many examiners disputed a virginity test and said it should not be imposed on them against their will. They also stated that this examination is not only a violation of human rights but also an unpleasant experience for some [17]. The results of our study are in this line.

In the present study, however, many midwives opposed virginity testing for “a man’s right to impose a virginity condition on marriage.” A few participants agreed with this issue, mostly due to the double standards or gender inequalities prevailing in Iranian society. It is approved by different groups of the population [23]. A study in the Philippines showed that men compared women’s personalities and values with their virginity [24]. Most participants agreed to have virginity testing “to investigate rape and sexual abuse.” In Gursoy et al.’s study, most midwives and nurses stated that a person has the right to request an examination, and she cannot be examined for virginity without her consent unless medically necessary. However, one-sixth of the nurses and midwives agreed that virginity testing could be done for the daughters at the parents’ request [17]. In Iran, the examination of virginity requires personal consent, but what seems important here is that in these traditional patriarchal societies, the preservation of women’s virginity is not only a sign of the girl’s pride but also of great importance for the girl’s family [25, 26]. Therefore, the family in these societies is one of the decision-makers in examining girls’ virginity. In our study, participants believed that for virginity testing, families and girls should be consulted to increase awareness, and it is important for examiners, especially midwives, to be aware of the sociocultural and legal consequences of virginity testing. Some participants in the study agreed that virginity testing should be considered by law at its own request and is illegal. Therefore, it seems that since virginity testing is recognized worldwide as an act against human rights and violence against women, national and international law should take this issue into account in formulating its programs. Christianson et al. [27] showed in their study that the majority of midwives participating in the study considered unexplained virginity testing to be a form of violence against women, and only a small percentage of them agreed to perform virginity testing.

According to the literature, no study investigated the relationship between the sociodemographic characteristics of people and their views. In the present study, some personal characteristics are significantly related to midwives’ views. It seems that people’s personal and social characteristics are rooted in their culture, which has influenced their views with the effects of people’s attitudes.

One of the limitations of this study was people may not have had enough time to answer the questionnaire questions; the questionnaire was given to them, and after one day, the people were contacted again, and the questionnaires were handed over to them.

The results showed that the midwives had a proper view of virginity testing and considered it a violation of women’s rights. Therefore, health system interventions should be aimed at improving the monitoring of the examination process and preventing adverse consequences in cases of negative test results. Community empowerment to prevent violence against women and comprehensive training of specialists for correct diagnosis and providing appropriate advice familiar with legal and personal laws should also be considered. In addition, emphasizing the training of the groups involved in this examination can reduce the psychological and physical effects caused by this examination.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Research Center for Ethics and Medical Law of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1399.490). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding

The authors received financial support from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualisation, study design, data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript: Somayyeh Naghizadeh, Mehri Robatjazi, Mahmoud Abbasi, and Azam Mohammadi; Data acquisition, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Somayyeh Naghizadeh, Azam Mohammadi, and Mehri Robatjazi; Statistical analysis: Somayyeh Naghizadeh and Azam Mohammadi; Supervision: Mahmoud Abbasi and Mehri Robatjazi; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank the cooperation of the Medical Ethics and Law Research Center of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, and the Islamic Azad University of Tabriz Branch.

References

Virginity testing is defined as an act and process of inspecting the genitals of unmarried girls and women to determine if they have had vaginal intercourse [1]. The primary purpose of this examination is sexual abstinence, delaying sexual intercourse until marriage, and preventing the spread of sexually transmitted diseases and AIDS in various cultures [2]. This examination is often performed in African and Asian countries. The growing number of virginity testing and repair applicants in European countries, including the Netherlands, Sweden, Spain, and Canada, without previous experience with such examinations indicates its globalization and the dominant role of cultural beliefs in accepting the test [3, 4, 5].

However, most societies accept virginity as an undeniable value [6]. Virginity testing without medical indication is questionable due to the double standard and violence against women [7]. The prevalence of virginity testing at personal request in some countries has become a matter of life and death due to virginity’s connection to the dignity of families and its consequences, such as notoriety, suicide, and honor killing [8, 9]. It has been criticized by human rights organizations [10]. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations special rapporteur have banned virginity testing as a form of inhumane, cruel, degrading, and sexual violence against women. However, this practice continues in many countries, including Iran [11]. Olson et al., in a review study, concluded that virginity testing is not only not good but also will cause physical, mental, and psychological damage to the person being examined [12].

On the other hand, according to the evidence in countries where the hymen is the virginity index, such examinations cause people to have oral sex, anal sex, and genital contact, which is often unprotected and leads to sexually transmitted diseases [13, 14].

However, planning and adopting appropriate policies related to virginity testing as a sociocultural product in any country requires studying. There are no clear instructions regarding virginity testing at the personal request of applicants and medical staff members involved in this examination and the country’s medical centers [11].

What seems to be important is that this examination is not done to protect or promote girls’ health and is, in fact, a violation of the patient’s rights because this examination is often performed without the person’s informed consent. The examination result without the person’s consent will be told to others, contrary to the principle of patient confidentiality. There may be issues following this announcement that the health system cannot respond to it [14, 15]. As a member of the virginity testing team, the midwife has professional ethical duties, such as showing respect to the person regarding the examination, preventing psychological injuries, physical and social, protecting individual rights, ensuring legal authorization for all steps, the confidentiality of personal information, understanding the patient’s feelings and, if necessary, act as a supporter for the person [16]. It is important that midwives, as individuals involved in this examination, must be aware of the relevant laws in this field to carry out their professional responsibilities and the resulting moral responsibilities [17]. In our country, Iran, midwives face many requests for examination of hymen and virginity membranes annually, but unfortunately, university education does not answer the questions that will arise for this group. Midwives may face many cultural, social, legal, psychological, and moral challenges in relation to performing or not performing this examination. Therefore, the present study investigated midwives’ views on virginity testing.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 210 midwives working in private offices, hospitals, health centers, and hospitals affiliated with Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz City, Iran, from January to August 2020. The inclusion criteria included midwives living in Tabriz working in one of the health centers, private clinics, or universities who were willing to participate in the study.

The sample size for this study was based on the results of the study of Zeyneloglu et al. [18]. Considering P=0.65, d=10% around p, and α=0.05, the sample size was 207 people, and the sample size was 210.

The researcher had to take samples from comprehensive health centers or private clinics; the sampling method in this study was different. Due to the small number of midwives working in universities, these midwives were selected by convenience sampling method; for midwives working in offices, health centers, and hospitals, a simple random method was used. First, the list of midwifery clinics, health centers, and hospitals in Tabriz was determined and then numbered in the order in which the samples were selected randomly. Also, according to the number of midwives working in each center, the sample was randomly selected using www.Random.org based on the number assigned to each.

Due to the lack of a standard questionnaire in this field, a researcher-made questionnaire was designed based on the questionnaires used by Robatjazi et al. [8], Gursoy and Vural [17], Zeyneloglu et al. [18], and Simbar et al. [19]. This questionnaire consists of two main parts.

The first part of the questionnaire was the sociodemographic characteristics, including age, work experience, marital status, occupation, place of work, education, ethnicity, religion, place of residence, and family financial status. Some questions include, “Have you ever been tested for virginity yourself?” “Do you have a single son, brother, daughter, or sister?” and “how much virginity testing have you done so far?”

The second part of the questionnaire had 55 questions (6 dimensions), emotions of the examined people (6 questions about the feelings of the examinees), consequences of virginity testing (11 questions), reasons for midwives’ desire to do or not to do virginity testing (11 questions), common causes of virginity testing (9 questions), the appropriate approach to virginity testing (7 questions), and respecting the rights of examinees (11 questions). This questionnaire was scored based on the 5-point Likert scale (totally agree, agree, no opinion, disagree, and totally disagree) with a total score of 55 to 275. Questions 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27, 28, and 48 are scored in reverse.

The validity of the questionnaire was assessed using face and content validity by emailing 10 experts, including members of the faculty of midwifery and reproductive health of the country’s medical universities, obstetricians, and forensic specialists. The Content Validity Index (CVI) and the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) were calculated according to the Lawshe table [20]. CVI and CVR were 0.86 and 0.82, respectively. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed by retesting for two weeks on 20 employed midwives. The internal correlation coefficient using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for the questions was calculated at 0.82.

The study data were gathered by referring to private clinics, health centers, and university centers, and comprehensive information on the reasons for conducting the research, benefits, results, confidentiality of data, and how to conduct the research was provided. To comply with the ethical aspects, participation in the study was voluntary, and they were assured that all information would remain confidential with the researcher. Participants could withdraw from the study at any stage. Also, we did not record the participants’ identities to protect privacy.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software, version 21. Descriptive statistics and the Pearson test, independent t-test, and one-way ANOVA were used to analyze data. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in this study are given in Table 1.

.jpg)

.jpg)

In examining the various dimensions of “emotions of the examined person on virginity testing,” most participants (more than 60%) agreed and totally agreed with considering the emotion of the examinees in virginity testing.

In examining the various dimensions of “emotions of the examined person on virginity testing,” most participants (more than 60%) agreed and totally agreed with considering the emotion of the examinees in virginity testing. Regarding the “consequences of virginity examination” dimensions questions, 40% agreed and totally agreed with the adverse consequences of virginity testing. Regarding the “reasons for midwives’ desire to do or not to do virginity testing,” 56.2% believed that “examining the virginity veil has no therapeutic value or even prevention of the problem and should not be done.” Regarding the “common causes of virginity testing” dimension, in the study of rape and sexual abuse, 29.5% strongly agreed; most midwives believed that one of the most common causes of virginity testing was to investigate rape and sexual abuse. Regarding the dimension of the “appropriate approach to virginity testing,” 45.5% strongly agreed, and 0.5% had opposite option about the question “awareness of examiners, especially midwives, about the cultural, social and legal consequences of virginity testing is important and necessary” (Table 2).

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Mean±SD of the overall score of the midwives’ view on virginity testing was 206.98±16.58 out of the score range of 159-258 (Table 3).

.jpg)

The variables of age (P=0.033), education level (P=0.001), place of residence (P=0.001), and place of employment (P=0.001) had a statistically significant difference with the overall score of midwives` views towards the virginity testing. Also, there was a statistically significant difference between the emotions of the examined person with the place of residence (P=0.001), place of employment (P=0.013), and the number of examinations performed by midwives (P=0.022). The reasons for midwivesʹ desire to do or not to do, was significant based on ethnicity (P=0.018) and place of employment (P=0.003). The variables of the place of employment (P=0.011) and personal history of virginity examination (P=0.001) were significate with the common causes of virginity testing and the variables of education level (P=0.001) and place of residence (P=0.001) with the dimension of the appropriate approach to virginity testing. Finally the variables of age (P=0.001), an education level (P=0.001), place of residence (P=0.028) work history (P=0.002), place of employment (P=0.002) and the number of virginity testing (P=0.022) with respecting the rights of examinees were statistically significant (Table 4).

.jpg)

Discussion

The present study’s findings indicate that most midwives agreed on “paying attention to the feelings of the examinees about the virginity testing.” This study showed that most participants believed that virginity testing caused physical and psychological pain and a kind of invasion of privacy in the examinee. This is consistent with a statement issued by a group of Denmark forensic experts [21] that considered pain, mental health problems, and disregard for the patient’s rights as the effects of virginity testing.

Most participants believed that virginity testing exacerbates feelings of gender inequality, increases physical and verbal violence, and decreases self-esteem. In a similar study, midwives believed virginity screening and hymen repair were patriarchal elements used to control violence against women [22]. Our result is consistent with them. Most midwives in our study believed that “virginity testing has no therapeutic or even preventive value and should not be done.” In Simbar et al.’s study, the most important reasons for virginity testing were professional performance and economic motivation [19]. Meanwhile, in our research, few midwives performed virginity testing for economic motivation. This difference can be attributed to the different cultural bases of the two studies. Gursoy’s study showed that many examiners disputed a virginity test and said it should not be imposed on them against their will. They also stated that this examination is not only a violation of human rights but also an unpleasant experience for some [17]. The results of our study are in this line.

In the present study, however, many midwives opposed virginity testing for “a man’s right to impose a virginity condition on marriage.” A few participants agreed with this issue, mostly due to the double standards or gender inequalities prevailing in Iranian society. It is approved by different groups of the population [23]. A study in the Philippines showed that men compared women’s personalities and values with their virginity [24]. Most participants agreed to have virginity testing “to investigate rape and sexual abuse.” In Gursoy et al.’s study, most midwives and nurses stated that a person has the right to request an examination, and she cannot be examined for virginity without her consent unless medically necessary. However, one-sixth of the nurses and midwives agreed that virginity testing could be done for the daughters at the parents’ request [17]. In Iran, the examination of virginity requires personal consent, but what seems important here is that in these traditional patriarchal societies, the preservation of women’s virginity is not only a sign of the girl’s pride but also of great importance for the girl’s family [25, 26]. Therefore, the family in these societies is one of the decision-makers in examining girls’ virginity. In our study, participants believed that for virginity testing, families and girls should be consulted to increase awareness, and it is important for examiners, especially midwives, to be aware of the sociocultural and legal consequences of virginity testing. Some participants in the study agreed that virginity testing should be considered by law at its own request and is illegal. Therefore, it seems that since virginity testing is recognized worldwide as an act against human rights and violence against women, national and international law should take this issue into account in formulating its programs. Christianson et al. [27] showed in their study that the majority of midwives participating in the study considered unexplained virginity testing to be a form of violence against women, and only a small percentage of them agreed to perform virginity testing.

According to the literature, no study investigated the relationship between the sociodemographic characteristics of people and their views. In the present study, some personal characteristics are significantly related to midwives’ views. It seems that people’s personal and social characteristics are rooted in their culture, which has influenced their views with the effects of people’s attitudes.

One of the limitations of this study was people may not have had enough time to answer the questionnaire questions; the questionnaire was given to them, and after one day, the people were contacted again, and the questionnaires were handed over to them.

The results showed that the midwives had a proper view of virginity testing and considered it a violation of women’s rights. Therefore, health system interventions should be aimed at improving the monitoring of the examination process and preventing adverse consequences in cases of negative test results. Community empowerment to prevent violence against women and comprehensive training of specialists for correct diagnosis and providing appropriate advice familiar with legal and personal laws should also be considered. In addition, emphasizing the training of the groups involved in this examination can reduce the psychological and physical effects caused by this examination.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Research Center for Ethics and Medical Law of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1399.490). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding

The authors received financial support from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualisation, study design, data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript: Somayyeh Naghizadeh, Mehri Robatjazi, Mahmoud Abbasi, and Azam Mohammadi; Data acquisition, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Somayyeh Naghizadeh, Azam Mohammadi, and Mehri Robatjazi; Statistical analysis: Somayyeh Naghizadeh and Azam Mohammadi; Supervision: Mahmoud Abbasi and Mehri Robatjazi; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank the cooperation of the Medical Ethics and Law Research Center of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, and the Islamic Azad University of Tabriz Branch.

References

- Ngubane L. Traditional practices and human rights: An insight on a traditional practice in Inchanga village of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. The Oriental Anthropologist. 2020; 20(2):315-31. [DOI:10.1177/0972558X20952969]

- Olson RM, García-Moreno C. Virginity testing: A systematic review. Reproductive Health. 2017; 14(1):61. [DOI:10.1186/s12978-017-0319-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Crosby SS, Oleng N, Volpellier MM, Mishori R. Virginity testing: Recommendations for primary care physicians in Europe and North America. BMJ Global Health. 2020; 5(1):e002057. [DOI:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002057] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Olamijuwon E, Odimegwu C. Saving sex for marriage: An analysis of lay attitudes towards virginity and its perceived benefit for marriage. Sexuality & Culture. 2022; 26(2):568-94. [DOI:10.1007/s12119-021-09909-7]

- Saharso S. Hymen repair: Views from feminists, medical professionals and the women involved in the middle east, North Africa and Europe. Ethnicities. 2022; 22(2):196-214. [DOI:10.1177/14687968211061582]

- Seanego D, Mogoboya M. Exploring the influence of virginity testing on the lives of female characters in zakes mda’s our lady of Benoni. Nveo-Natural Volatiles & Essential Oils. 2022; 9(1): 252-260. [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01876.x]

- Rafudeen A, Mkasi LP. Debating virginity-testing cultural practices in South Africa: A taylorian reflection. Journal for the Study of Religion. 2016; 29(2):118-33. [Link]

- Robatjazi M, Simbar M, Nahidi F, Gharehdaghi J, Emamhadi M, Vedadhair A, et al. Virginity and virginity testing: Then and now. International Journal of Medical Toxicology and Forensic Medicine. 2016; 6(1):36-43. [DOI:10.22037/ijmtfm.v6i1(Winter).10021]

- Robatjazi M, Abbasi M. [Self-request virginity testing: Attitudes and approaches (Persian)]. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2020; 22(11):75-84. [DOI:10.22038/IJOGI.2020.14956]

- Ayuandini S. Finger pricks and blood vials: How doctors medicalize 'cultural' solutions to demedicalize the 'broken' hymen in the Netherlands. Social Science & Medicine. 2017; 177:61-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.016] [PMID]

- Robatjazi M, Simbar M, Nahidi F, Gharehdaghi J, Emamhadi M, Vedadhir AA, et al. Virginity testing beyond a medical examination. Global Journal of Health Science. 2015; 8(7):152-64. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v8n7p152] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Olson RM, García-Moreno C. Virginity testing: A systematic review. Reproductive Health. 2017; 14(1):61. [DOI:10.1186/s12978-017-0319-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kacha TG, Lakdawala BM. Sex knowledge and attitude among medical interns in a tertiary care hospital attached to medical college in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. Journal of Psychosexual Health. 2019; 1(1):70-7. [DOI:10.1177/2631831818821540]

- Mehrolhassani MH, Yazdi-Feyzabadi V, Mirzaei S, Zolala F, Haghdoost AA, Oroomiei N. The concept of virginity from the perspective of Iranian adolescents: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):717. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-08873-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Honarvar B, Salehi F, Barfi R, Asadi Z, Honarvar H, Odoomi N, et al. Attitudes toward and experience of singles with premarital sex: A population-based study in Shiraz, southern Iran. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2016; 45(2):395-402. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-015-0577-2] [PMID]

- O'Laughlin DJ, Strelow B, Fellows N, Kelsey E, Peters S, Stevens J, et al. Addressing anxiety and fear during the female pelvic examination.Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2021; 12:2150132721992195. [DOI:10.1177/2150132721992195] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Gürsoy E, Vural G. Nurses' and midwives' views on approaches to hymen examination. Nursing Ethics. 2003; 10(5):485-96. [DOI:10.1177/096973300301000505] [PMID]

- Zeyneloğlu S, Kısa S, Yılmaz D. Turkish nursing students' knowledge and perceptions regarding virginity. Nurse Education Today. 2013; 33(2):110-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2012.01.016] [PMID]

- Simbar M, Rahmanian F, Ramezani Tehrani F. Explaining the experiences and perceptions of gynecologists and midwives about virginity examination and it’s outcomes: A qualitative Study. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility 2015; 18(173):1-22. [Link]

- Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology. 1975; 28(4):563-75. [DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x]

- Independent Forensic Expert Group. Statement on virginity testing. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 2015; 33:121-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.jflm.2015.02.012] [PMID]

- Leye E, Ogbe E, Heyerick M. Doing hymen reconstruction: An analysis of perceptions and experiences of Flemish gynaecologists. BMC Womens Health. 2018; 18(1):91. [DOI:10.1186/s12905-018-0587-z] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rahmani A, Merghati-Khoei E, Moghadam-Banaem L, Hajizadeh E, Hamdieh M, Montazeri A. Development and psychometric evaluation of the premarital sexual behavior assessment scale for young women (PSAS-YW): An exploratory mixed method study. Reproductive Health. 2014; 11:43. [DOI:10.1186/1742-4755-11-43] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Manalastas EJ, David CC. Valuation of women’s virginity in the philippines. Asian Women. 2018; 34(1):23-48. [DOI:10.14431/aw.2018.03.34.1.23]

- Benbrahim Z, El Mekkaoui A, Lahmidani N, Ismaili Z, Mellas N. Gastric cancer: An epidemiological overview. Epidemiology. 2017; 7(2):304. [DOI:10.4172/2161-1165.1000304]

- Mulumeoderhwa M. Virginity requirement versus sexually-active young people: What girls and boys think about virginity in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2018; 47(3):565-75. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-017-1038-x] [PMID]

- Christianson M, Eriksson C. Acts of violence: Virginity control and hymen (re) construction. British Journal of Midwifery. 2014; 22(5):344-52. [DOI:10.12968/bjom.2014.22.5.344]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2023/06/25 | Accepted: 2023/06/20 | Published: 2023/06/20

Received: 2023/06/25 | Accepted: 2023/06/20 | Published: 2023/06/20

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |