Wed, Jan 28, 2026

Volume 35, Issue 4 (9-2025)

JHNM 2025, 35(4): 296-306 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nasiri N, Pakseresht S, Jafarzadeh-Kenarsari F, Maroufizadeh S, Roshan Chesli S. Comparison of Perceived Social Support and Domestic Violence Between Fertile and Infertile Women in North of Iran. JHNM 2025; 35 (4) :296-306

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-1885-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-1885-en.html

Nadia Nasiri1

, Sedigheh Pakseresht *2

, Sedigheh Pakseresht *2

, Fatemeh Jafarzadeh-Kenarsari3

, Fatemeh Jafarzadeh-Kenarsari3

, Saman Maroufizadeh4

, Saman Maroufizadeh4

, Shokoufeh Roshan Chesli5

, Shokoufeh Roshan Chesli5

, Sedigheh Pakseresht *2

, Sedigheh Pakseresht *2

, Fatemeh Jafarzadeh-Kenarsari3

, Fatemeh Jafarzadeh-Kenarsari3

, Saman Maroufizadeh4

, Saman Maroufizadeh4

, Shokoufeh Roshan Chesli5

, Shokoufeh Roshan Chesli5

1- Midwifery (MSc), Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Professor, Department of Midwifery, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,paksersht@yahoo.com

3- Associate Professor, Department of Midwifery, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

5- Instructor, Department of midwifery, Ra.C., Islamic Azad University, Rasht, Iran.

2- Professor, Department of Midwifery, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,

3- Associate Professor, Department of Midwifery, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- Assistant Professor, Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

5- Instructor, Department of midwifery, Ra.C., Islamic Azad University, Rasht, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 562 kb]

(216 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (423 Views)

Full-Text: (154 Views)

Introduction

Infertility is defined as the inability to achieve a successful pregnancy after one year of unprotected sexual intercourse [1]. Infertility can occur in two forms: Primary and secondary infertility. Primary infertility means that the individual has never experienced pregnancy, while secondary infertility occurs when the individual, despite having a history of pregnancy (regardless of whether it resulted in miscarriage or live birth), is unable to conceive after one year or more of regular unprotected intercourse [2].

Worldwide, approximately 186 million people suffer from infertility, with most cases occurring in developing countries [3]. According to the statistics from the centers for disease control and prevention, about 6 percent of women aged 15-44 are affected by infertility [4]. In an Iranian systematic review and meta-analysis, the prevalence of infertility was reported to be 7.88% [5], the prevalence of infertility in different regions of Iran was reported to vary, with an estimate of 23.81% in Guilan Province [6]. Infertility is considered a global health issue with physical, psychological, and social dimensions, and it can even affect interpersonal, social, and marital relationships, threatening individuals’ psychological and social well-being [7, 8].

The social-psychological consequences of female infertility are classified into six main groups: Quality of life (QoL), depression, anxiety, social support, sexual function, and violence [9]. One of the important psychological consequences of infertility for women is violence [10]. Violence against women is considered a major clinical health issue and a violation of women’s human rights, rooted in gender inequalities [11]. Violence has various forms that can come from a spouse (former spouse) or partner and differ in frequency and severity; psychological violence involves the use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the intent to cause mental or emotional harm; physical violence occurs when an individual uses hitting, kicking, or physical force to try to harm their partner; sexual violence involves coercion or attempts to force a partner to engage in a sexual act, sexual contact, or a non-physical sexual event, despite the individual not consenting or being unable to consent [12].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that globally, one in three women experiences physical, psychological, or sexual violence in their lifetime, primarily inflicted by their spouse or partner [13, 14]. In Iran, 71% of women experience violence in the past year [15], including psychological/verbal violence (58%), physical violence (25.2%), and sexual violence (10%)[16]. Iranian pregnant women also experience partner violence at a rate of 48.5%, which is mainly emotional violence (45.5%) [17]. The prevalence of domestic violence in Iran against infertile women varies from 14 to 88% [18]; and violence against infertile women in three dimensions—psychological (52.4%), physical (34%), and sexual (27.2%)—has been higher compared to fertile women [19]. Since infertile women are at risk of violence, they need social support; this improves the life satisfaction of infertile women and, by reducing anxiety, depression, negative self-perception, and hostility, increases their resilience, especially during infertility treatment. Therefore, attention to social support in women’s infertility is impactful and important [10, 20, 21]. Social support means providing material and emotional support from close ones to an individual who is exposed to stressful or difficult conditions [22]. With increased support from spouses, the incidence of postpartum depression in women decreases [23]. There is also a significant positive correlation between perceived social support (from family, friends, and significant others) and adaptation to infertility and QoL [24]. With increasing age and marriage age, perceived social support in infertile women also increases [25].

In some studies, infertile women and those who conceal their infertility have been reported to have lower perceived social support from significant others (spouse or partner) [26-31]. However, in another study, perceived social support was reported to be higher in infertile women than in fertile women [32]. Considering the contradictions in the results of some studies conducted in this regard, as well as the higher prevalence of infertility and cultural and social differences in Iran, the present study aims to determine and compare perceived social support and domestic violence among fertile and infertile women in northern Iran.

Materials and Methods

This is a case-control study conducted on 344 eligible women who were selected using a convenience sampling method from among those visited two infertility treatment and gynecology clinics of Al-Zahra Hospital in Rasht, north of Iran, in 2021. The sample size was first obtained as 130 per group based on the formula, considering the type I error (α) of 0.05, the type II error (β) of 0.2, and an effect size (d) of 0.35. Then, considering a 15% sample dropout and to increase the accuracy of the results, the sample size increased to 172 in each group. The inclusion criteria for fertile women were history of at least one pregnancy, having at least one child, no previous or current history of infertility, and no pregnancy at the time of the study. The inclusion criteria for infertile women were the confirmation of infertility by a gynecologist and having an infertility file. The general inclusion criteria for both groups were the literacy to answer questions, being Iranian, being able to understand and speak Persian, living with a spouse, no chronic heart or lung diseases, blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, no medication use, and no mental disorders (based on self-report or medical file), and willingness to participate in the study and complete the questionnaires. During the study period, 775 women referred to the infertility treatment clinic and 3430 women to the gynecology clinic, of whom 442 were eligible to participate in the study. Finally, 344 eligible women were included, 172 infertile women as the case group and 172 fertile women as controls.

The instruments included a sociodemographic/fertility profile form, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), and the domestic violence sale. The sociodemographic/fertility profile form surveys age, education and occupation of the woman, education and occupation of the husbands, family income status, number of marriages, age at marriage, duration of marriage, place of residence, living with the husband’s family, cause of infertility, duration of infertility, number of infertility treatments, number of infertility treatment failures, and type of infertility (primary and secondary). The domestic violence sale adapted from the WHO violence against women instrument and the Hurt-Insult-Threaten-Scream (HITS) domestic violence screening tool [33, 34] that was developed by Azadarmaki et al. [35]. This tool is a 20-item, self reported questionnaire with three Components: Psychological (7 items), Physical (9 items), and Sexual (4 items). The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (never=0, rarely=1, sometimes=2, often=3, and always=4). The total score ranges from 0 to 80, with higher scores indicating higher levels of domestic violence [35]. The MSPSS is a 12-item tool developed by Zimet et al. [36] that measures perceived social support in three domains: Family, friends, and significant other (spouse or partner). Each domain has 4 items that are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, no opinion, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree). The total score ranges from 12 to 84, with higher scores indicating greater social support. The Persian version of this tool has been validated by Bagherian-Sararoudi et al. [37].

After receiving the introduction letter and obtaining permission, the researcher visited the clinics in Rasht to collect data twice in the morning and evening shifts. After explaining the study objectives and methods, and emphasizing the confidentiality of the data, written informed consent was obtained from the participants, and the questionnaires were completed. After collecting the data, they were analyzed in SPSS software, version 16 using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and multiple linear regression analysis, considering a significance level of P<0.05.

Results

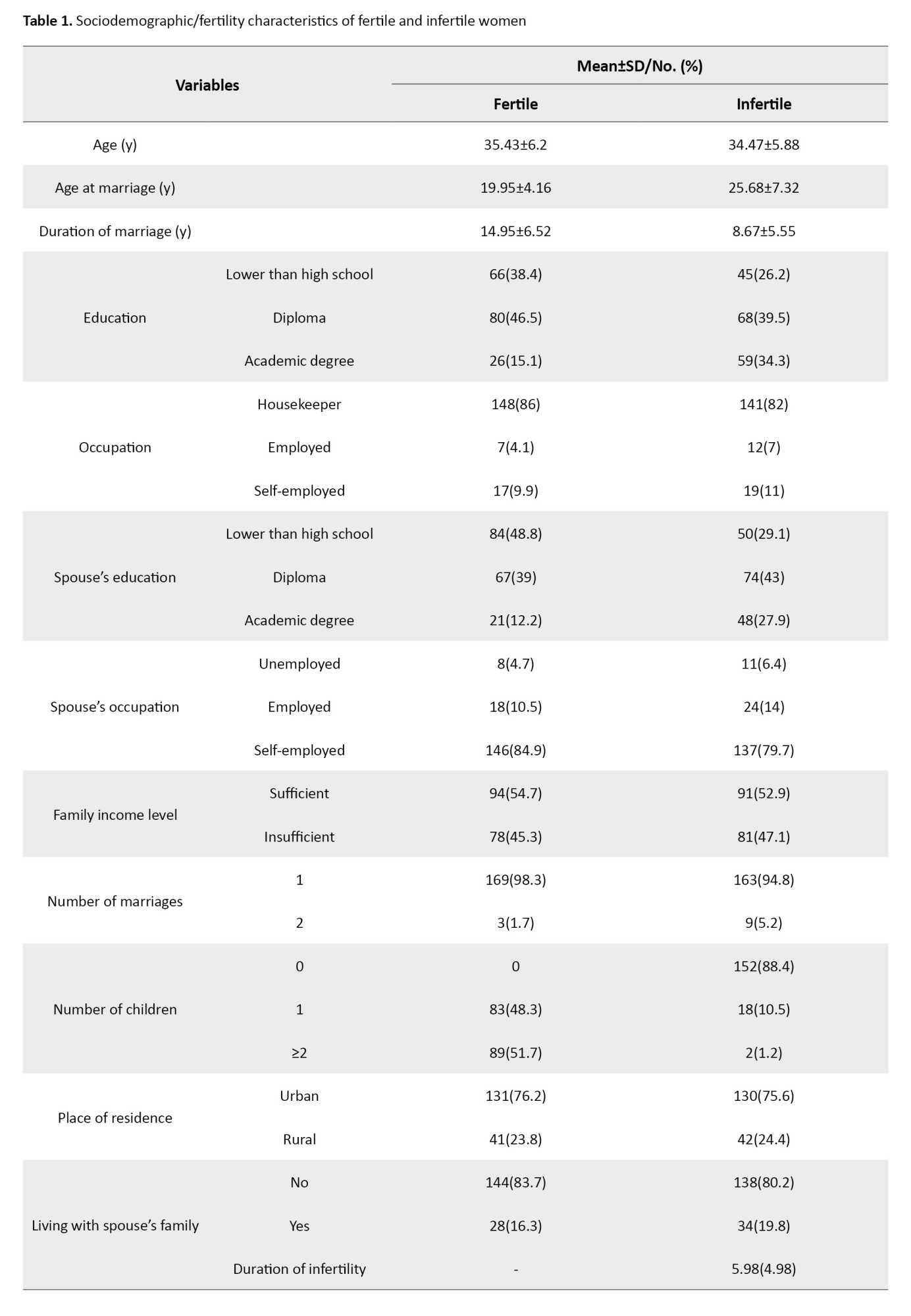

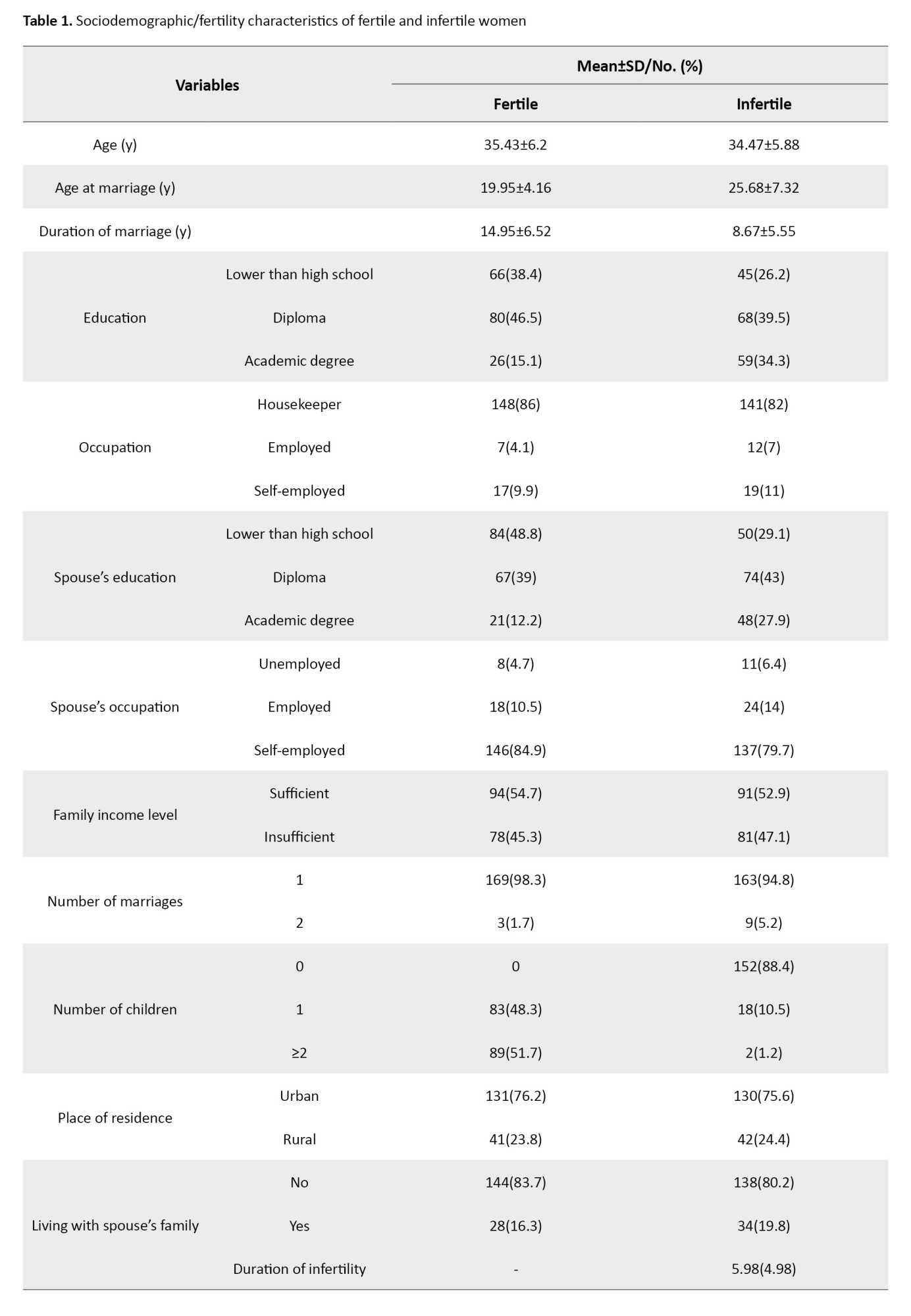

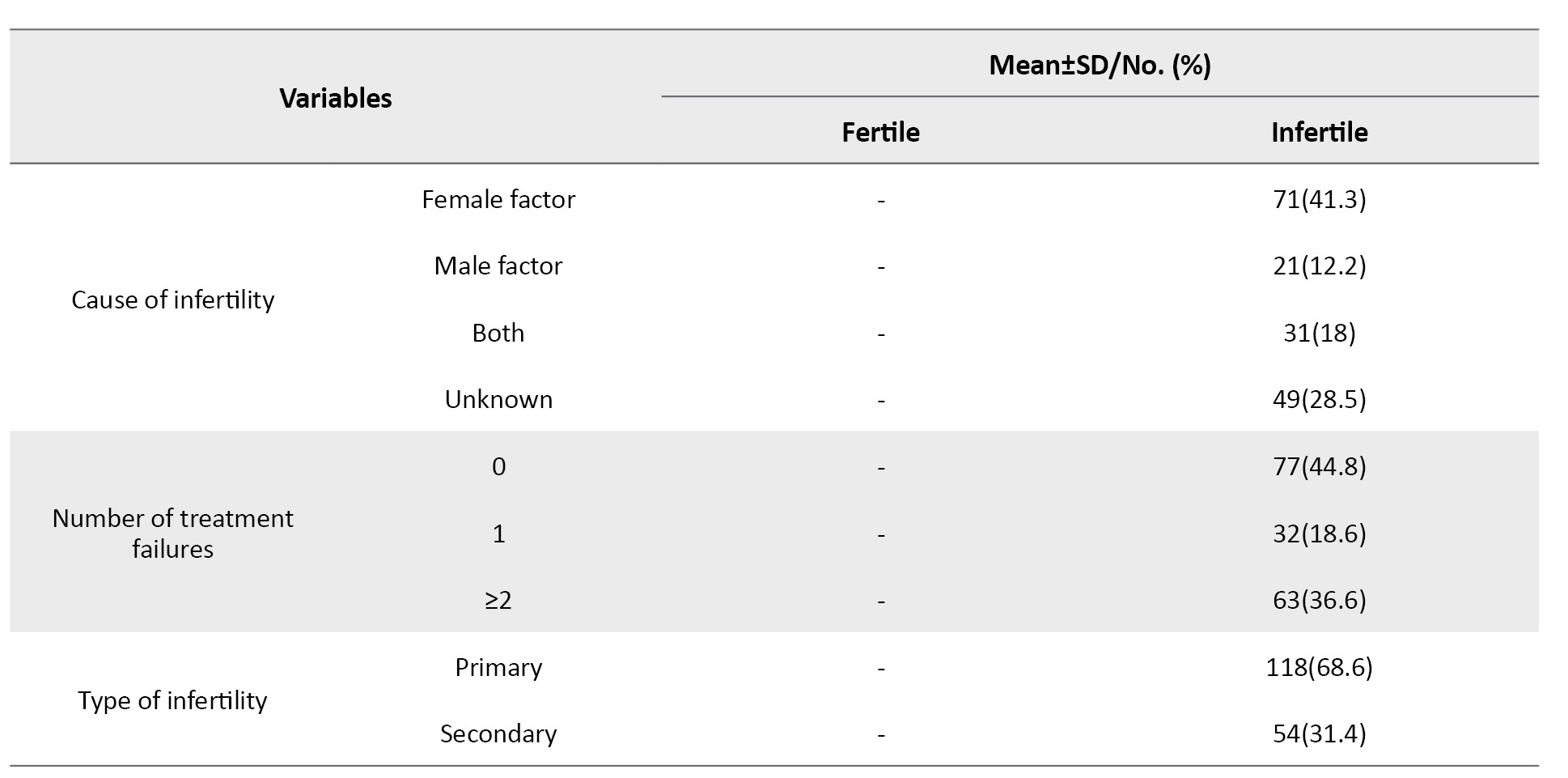

The mean age, age at marriage, and duration of marriage of fertile and infertile women were 35.43±6.2, 34.47±5.88, 19.95±4.16, 25.68±7.32, 14.95±6.52, and 8.67±5.55 years, respectively. The sociodemographic/fertility characteristics of the women are presented in Table 1.

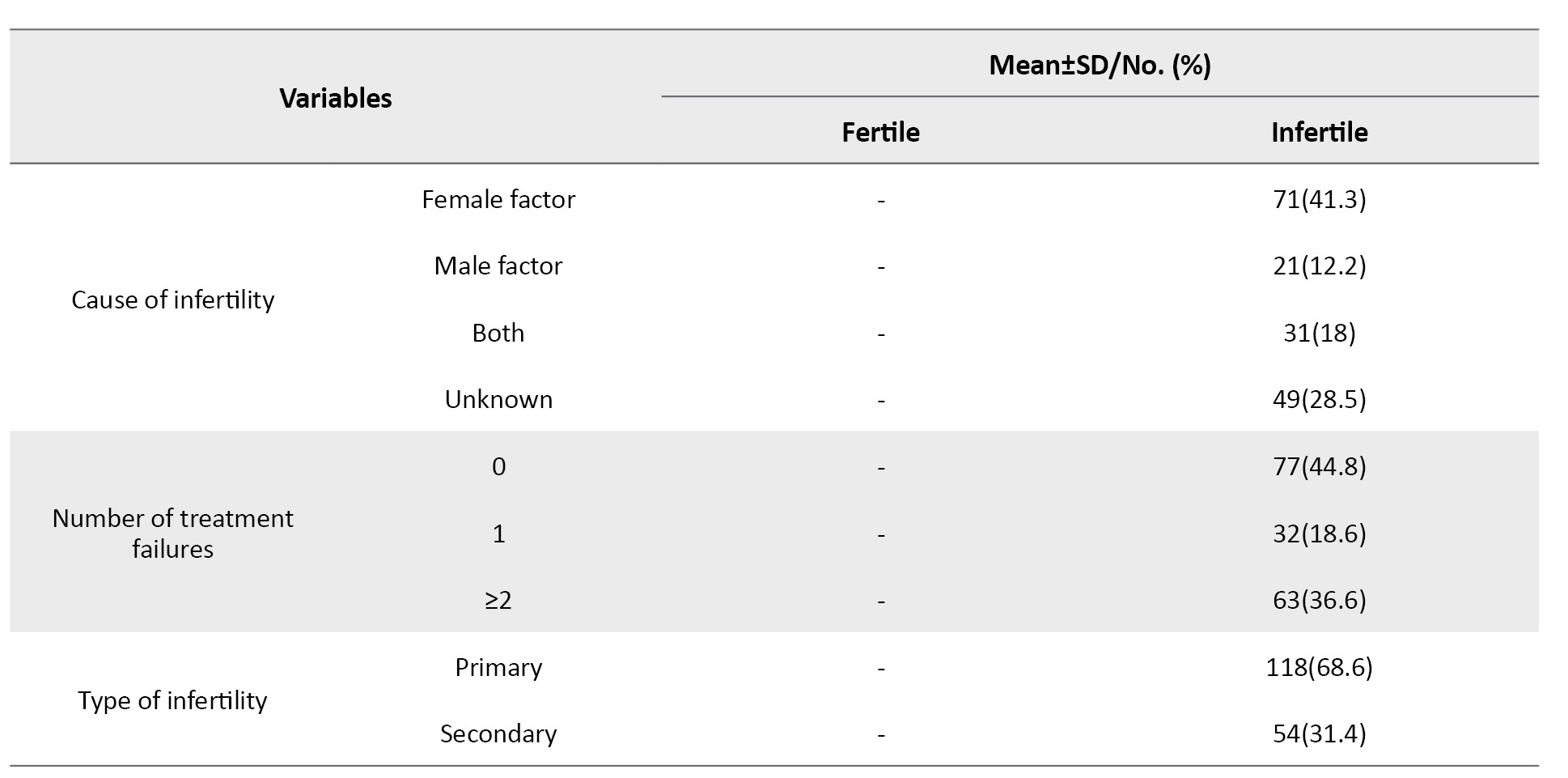

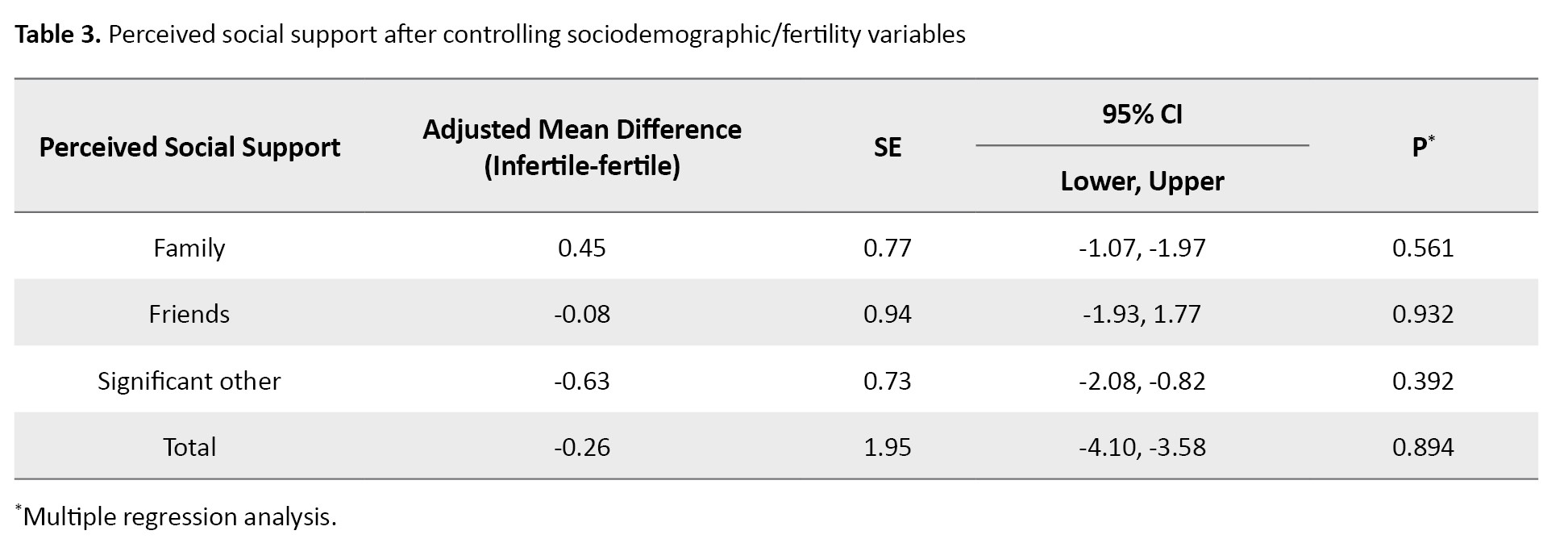

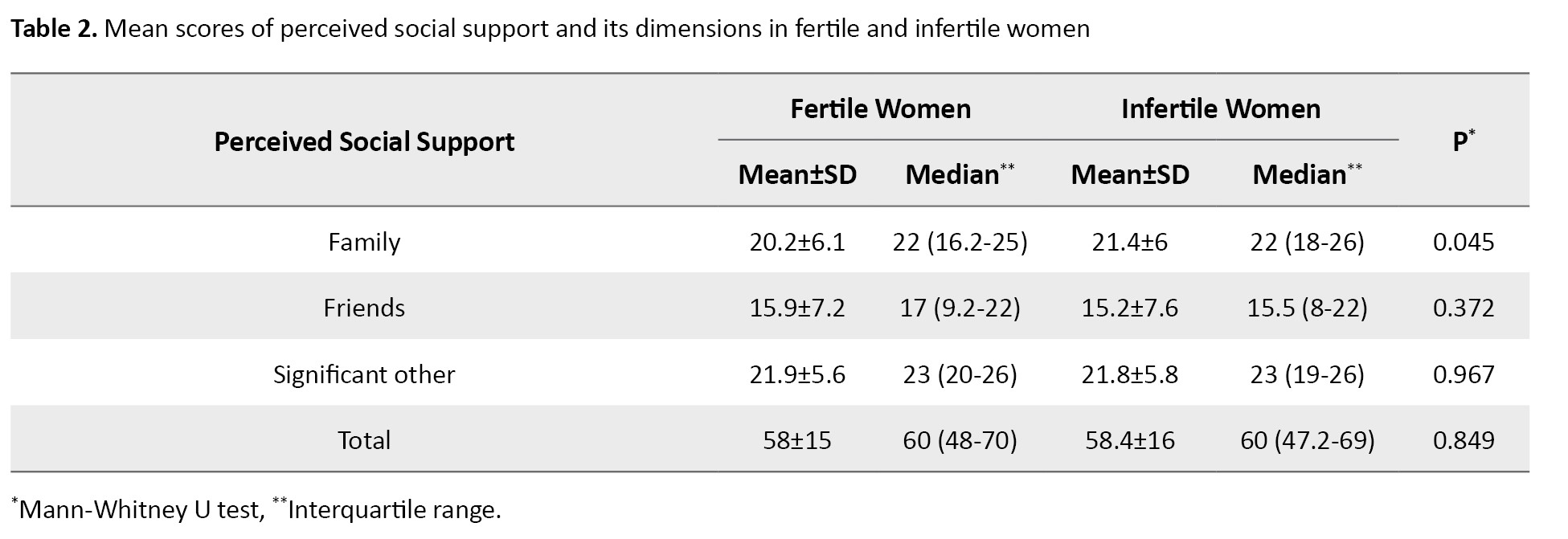

The findings showed that 51.7% of fertile women had two or more children and 88.4% of infertile women had no children. Based on the chi-square test and independent t-test results, there was a statistically significant difference in the variables of age at marriage (P=0.001), duration of marriage (P=0.001), women’s education (P=0.001), spouse’s education (P=0.001), and number of children (P=0.001) between the two groups of fertile and infertile women. However, no statistically significant difference was observed in other sociodemographic/fertility variables. The Mann-Whitney U test results (Table 2) showed no statistically significant difference in the total MSPSS score and in the dimensions of friends and significant other between fertile and infertile women, but the family dimension score was significantly higher in infertile women than in fertile women (P=0.045).

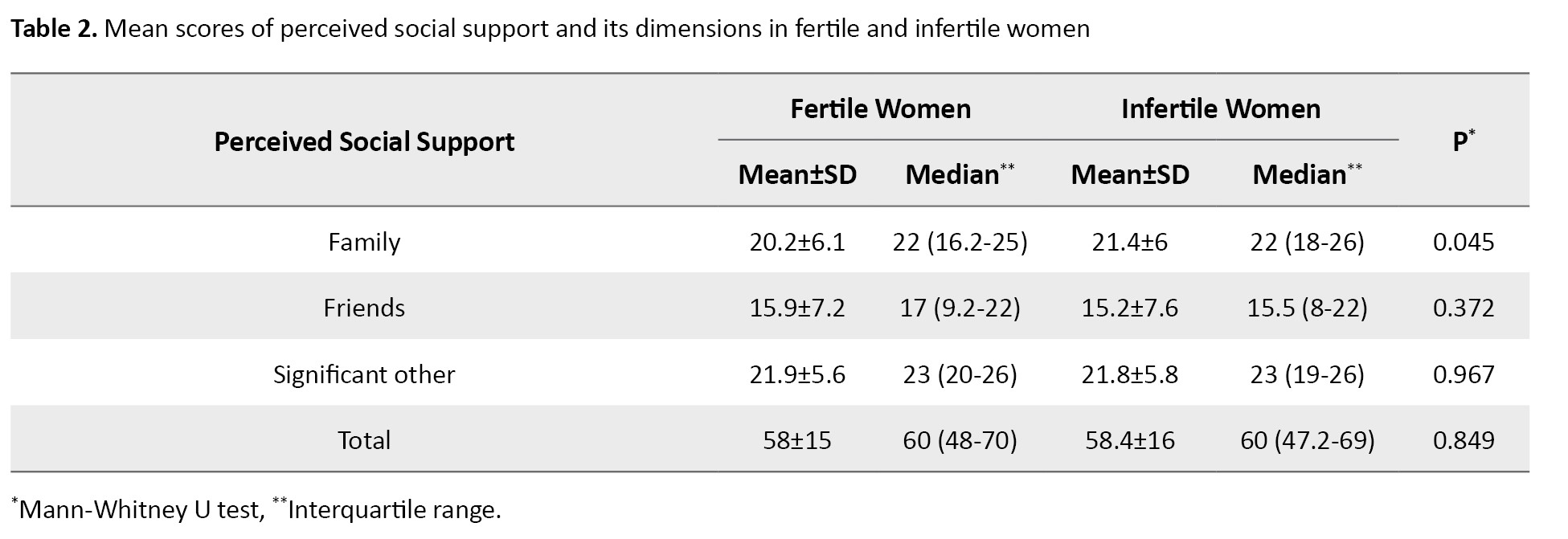

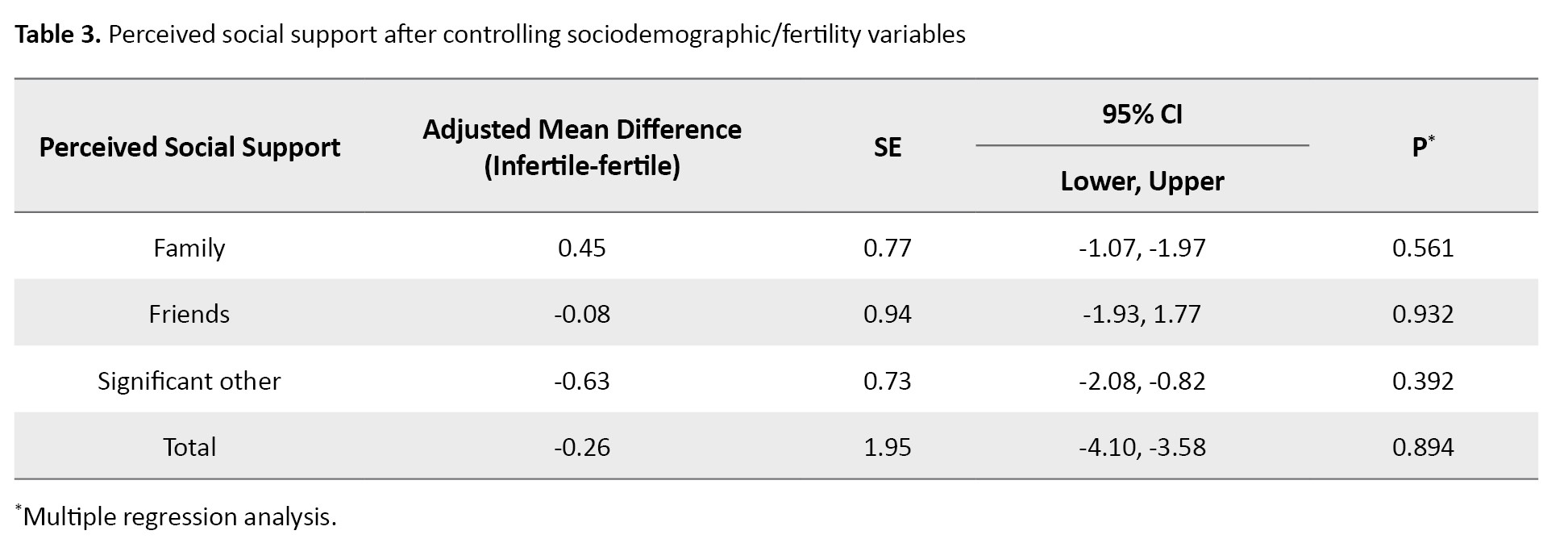

After controlling for sociodemographic/fertility variables using multiple linear regression analysis, the results showed no significant association of the total score and the dimensions of MSPSS with fertility/infertility (Table 3).

The Mann-Whitney U test results (Table 4) showed that the total score of domestic violence in infertile women was significantly lower than in fertile women (P=0.001).

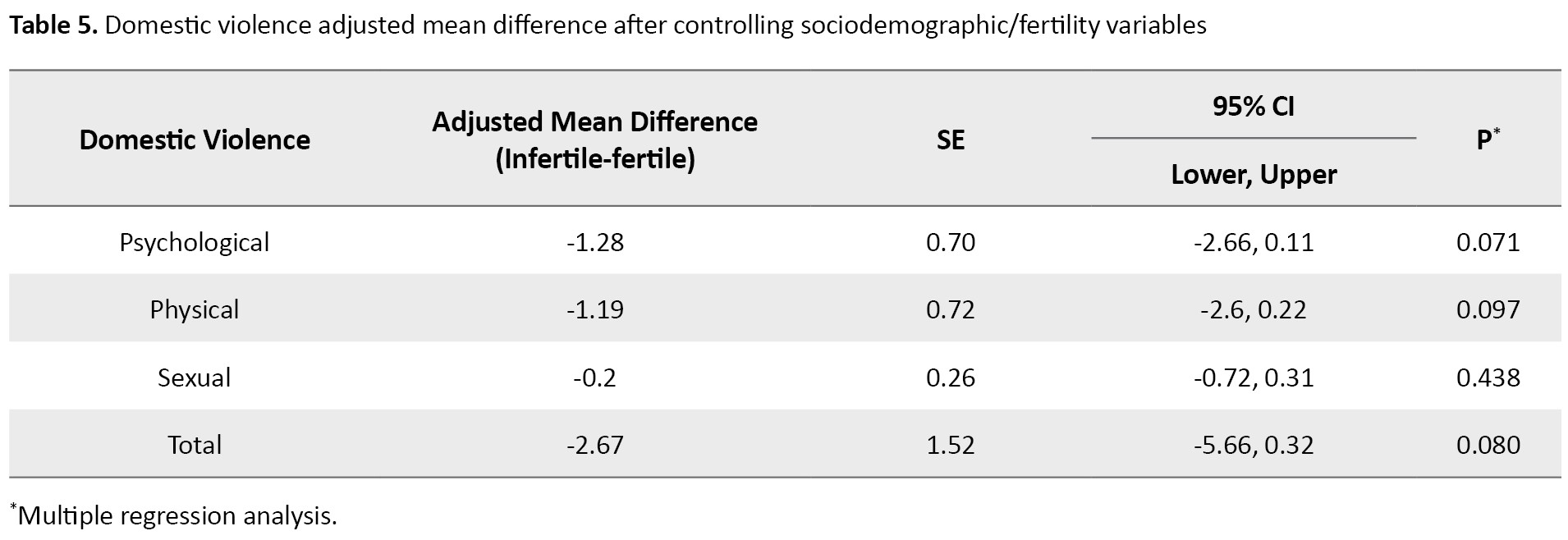

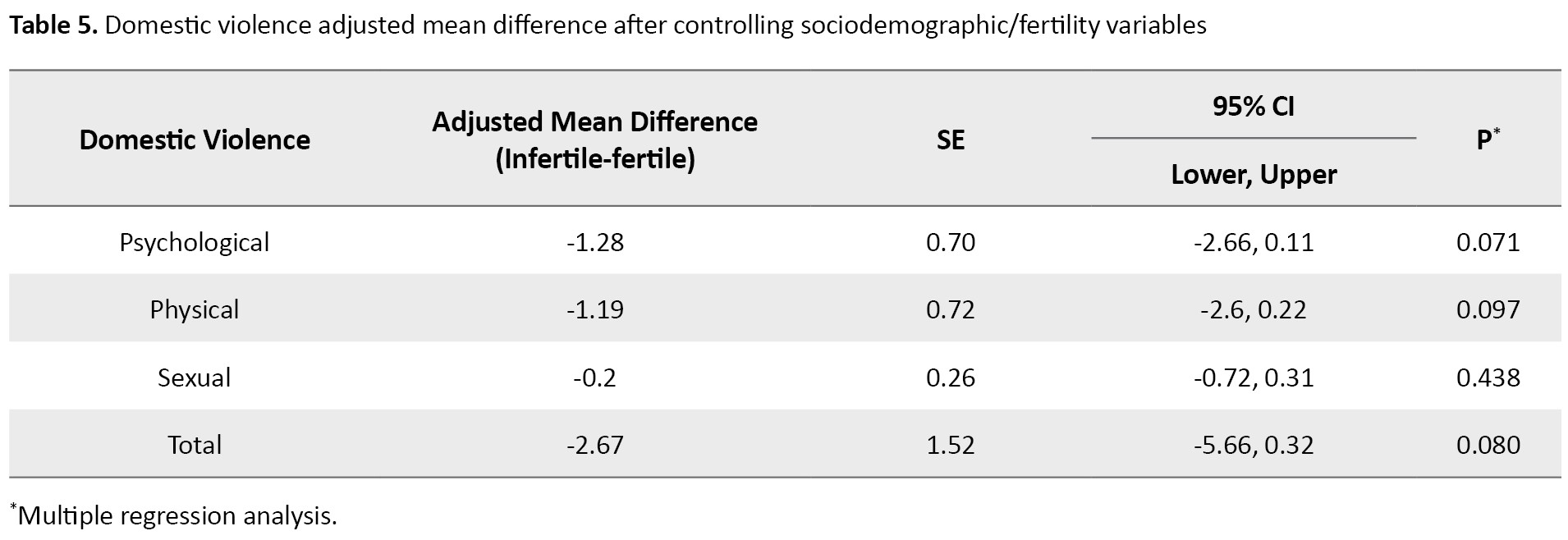

The scores of psychological (P=0.001), physical (P=0.001), and sexual (P=0.013) dimensions were also significantly lower in infertile women. After controlling for sociodemographic/fertility variables using multiple linear regression analysis, the results showed no significant association of the total score and the dimensions of domestic violence with fertility/infertility (Table 5).

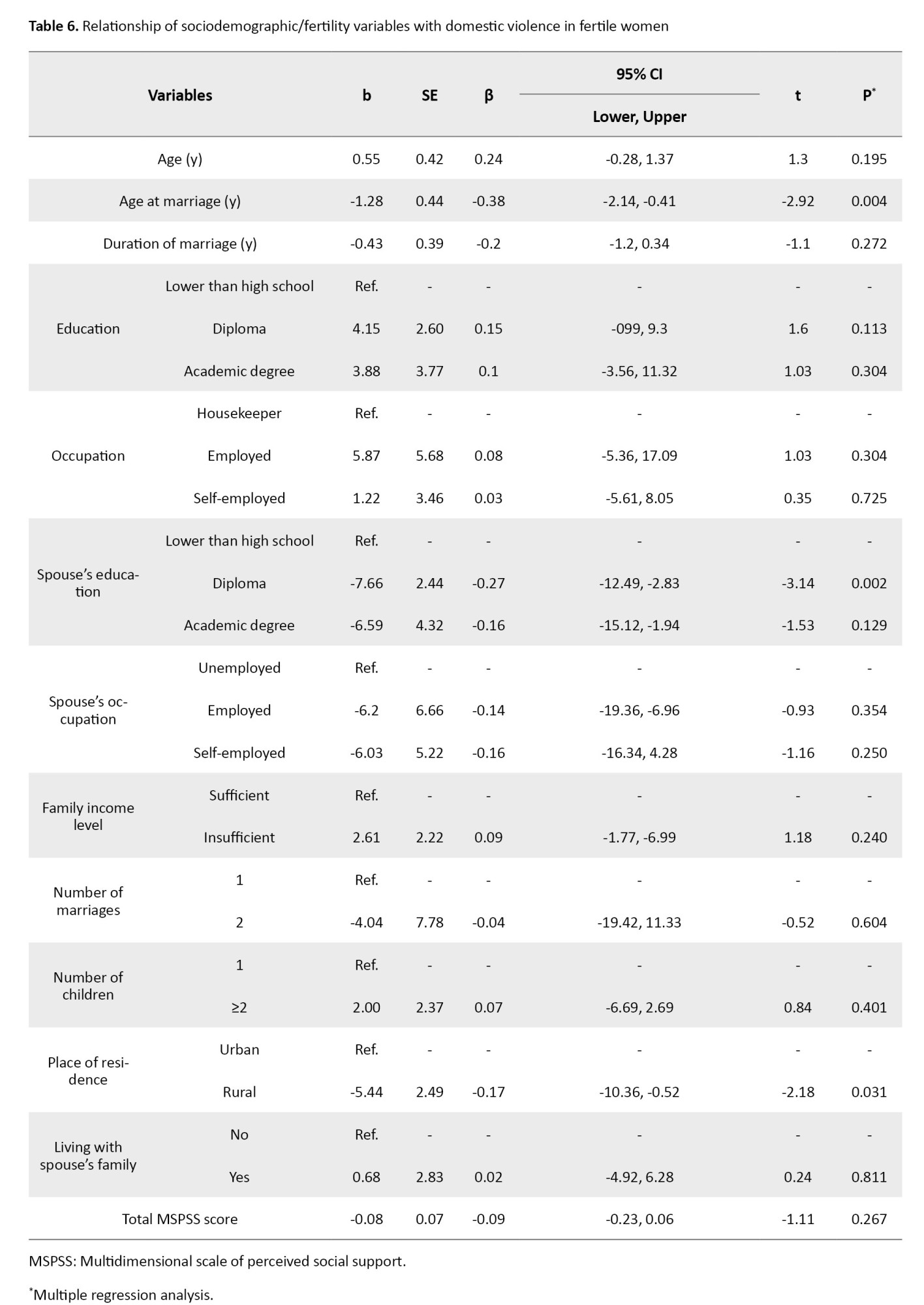

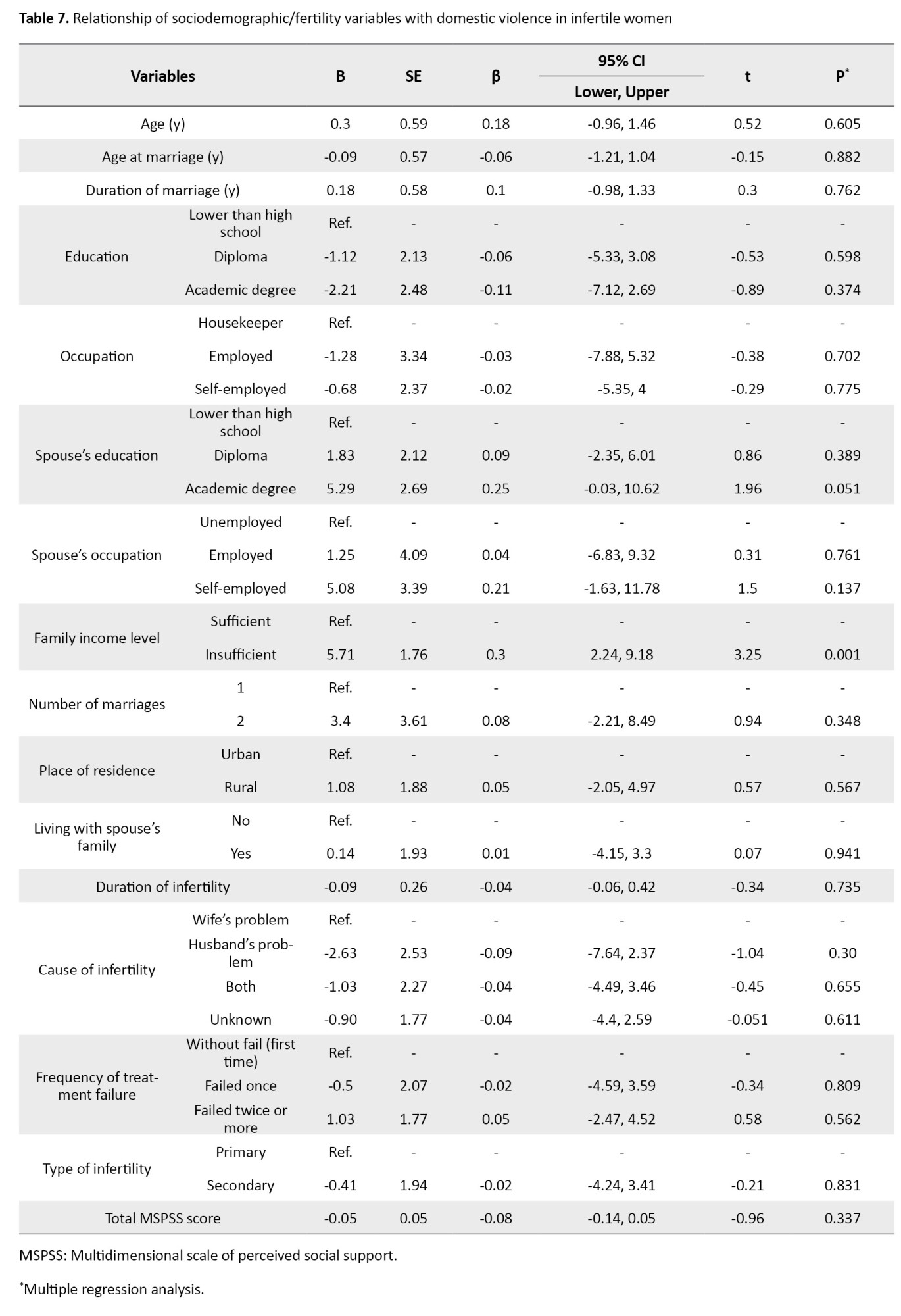

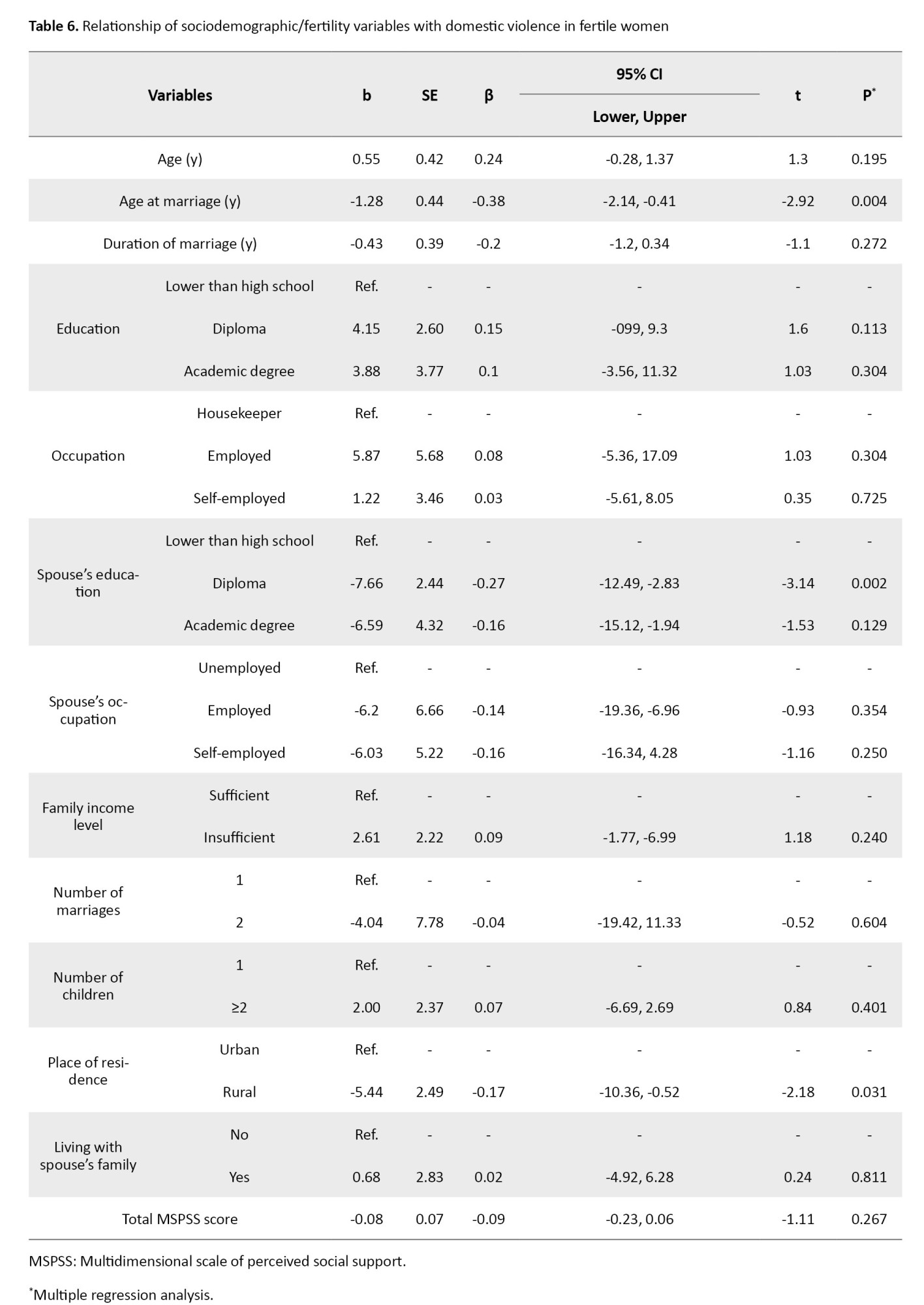

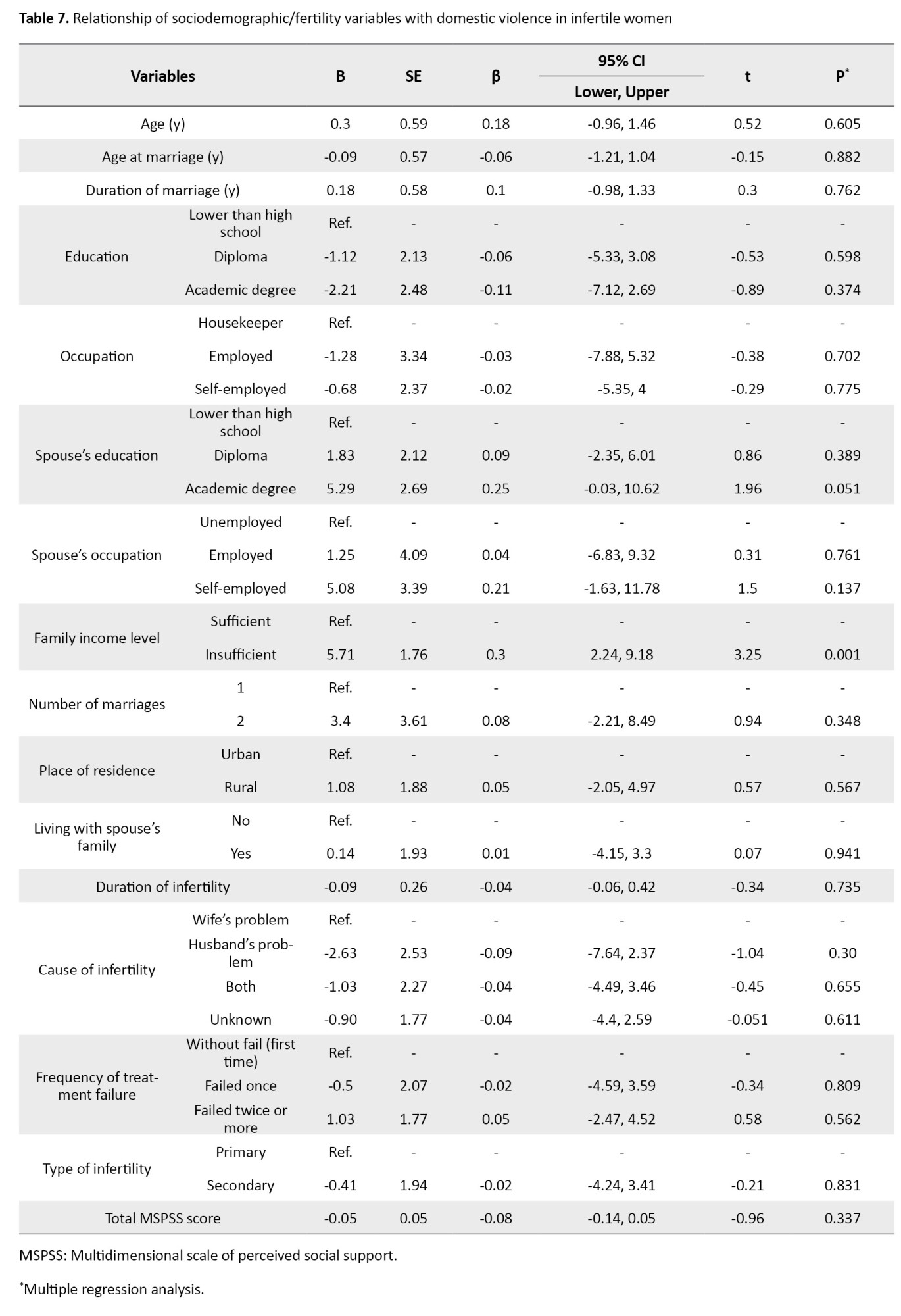

According to the regression coefficients, in fertile women, only family income level (P=0.008, b=-6.43) had a statistically significant relationship with perceived social support, while in infertile women, family income status (P=0.034, b=-6.18) and women’s occupation (P=0.008, b=14.58) had a statistically significant relationship with perceived social support. There was a statistically significant relationship between the total score of domestic violence and age at marriage (P=0.004, b=-1.28), husband’s education (P=0.002, b=-7.66), and place of residence (P=0.031, b=-5.44) in fertile women, while the total score of domestic violence in infertile women had a statistically significant relationship only with family income level (P=0.001, b=5.71) (Tables 6 and 7).

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that although the total score of domestic violence in infertile women was lower in fertile women, the difference was not statistically significant, which is in line with the results of Ghoneim et al. [38], while a study showed that the rate of sexual violence in infertile women was significantly higher than in fertile women [39]. Also, the results of the present study are against the results of some other studies [40, 41], which may be due to the lower age of infertile women and the difference in infertility duration, place of residence, living arrangement, educational level of the husbands of infertile women, the used instrument, and sample size.

The total domestic violence score of fertile women showed a significant decrease with the increase of age at marriage. A study [42] showed that employed or high-income people had less intimate partner violence. The results of another study [43] showed that as women’s age increases, the rate of domestic violence against them decreases. The results of the present study are not consistent with their results, which can be due to the sample size and the data collection method.

The total score of domestic violence in infertile women had a statistically significant relationship only with income status. The results of a study found the score of domestic violence was directly related to the duration of infertility, duration of marriage, and duration of infertility treatment, and indirectly related to the age at marriage [44]. However, the results of another study showed that the score of domestic violence was lower in women with high school education than in women with university education [39]. This difference may be due to the difference in the age of women, the type of infertility (primary or secondary), or the instrument used in the study.

According to the results of the present study, there was no statistically significant difference in the total score of perceived social support and its domains between fertile and infertile women, which is consistent with the results of Navid et al. [45], while is against the results of other studies [46, 47], perhaps due to difference in the instrument and sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

Perceived social support was not a relevant variable for domestic violence against either fertile or infertile women.The results of a study [48] showed that, in fertile women, there was a positive and significant correlation between perceived social support in the domains of family and significant other and marital satisfaction of couples. Another study reported a positive and significant correlation between perceived social support and life satisfaction in pregnant women [49], which indicates that perceived social support plays a fundamental role in women’s lives.The results of a study showed that social support was higher in infertile women than in fertile women [33], but fertile women experienced more violence. Differences in the instruments used to measure social support and violence, the unreliability of data collection using an online method, less racial diversity (most participants were white and highly educated), and limited access to the Internet may be reasons for the inconsistency of the results of the present study with those of the mentioned study.

Overall, it can be said that domestic violence is less common in Iranian infertile women than in fertile peers, and Perceived social support was not a relevant variable for domestic violence against either fertile or infertile women. In this study, the family income level of 47.1% of infertile women was not sufficient, therefore it is suggested that governmental and private organizations take actions to support or provide financial facilities to infertile couples. It is also recommended that healthcare providers, as physical and psychological supporters of infertile/fertile women, assess and identify the factors that can be effective in preventing, occurring, reducing, or increasing domestic violence and perceived social support, in order to increase perceived social support and reduce domestic violence among these women.

One of the limitations of this study was the possibility of women’s biased responses to questions related to domestic violence due to cultural, social issues, or shame. Other limitations were the lack of follow-up due to economic issues or refusal of the spouse to seek infertility treatment. Also, these results may not be generalizable to all women in Iran, since data were collected from only one teaching-treatment center in north of Iran. Since the allocation in this study was not done randomly, there is a risk of selection bias. It is recommended that future research, considering data collection from multiple centers, assess the impact of social desirability responding bias on the validity of the results. Also, given the cross-sectional design of the present study, future observational (cohort) studies should be conducted to more accurately examine the outcomes.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC. 2018.34). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after describing the study objectives. They were free to leave the study at any time.

Funding

This article was extracted from a research project and financially supported by Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Methodology and data analysis: Saman Maroufizadeh; Data collection: Nadia Nasiri; Writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants and the staff of the infertility treatment and gynecology clinics of Al-Zahra Hospital, Rasht, Iran.

References

Infertility is defined as the inability to achieve a successful pregnancy after one year of unprotected sexual intercourse [1]. Infertility can occur in two forms: Primary and secondary infertility. Primary infertility means that the individual has never experienced pregnancy, while secondary infertility occurs when the individual, despite having a history of pregnancy (regardless of whether it resulted in miscarriage or live birth), is unable to conceive after one year or more of regular unprotected intercourse [2].

Worldwide, approximately 186 million people suffer from infertility, with most cases occurring in developing countries [3]. According to the statistics from the centers for disease control and prevention, about 6 percent of women aged 15-44 are affected by infertility [4]. In an Iranian systematic review and meta-analysis, the prevalence of infertility was reported to be 7.88% [5], the prevalence of infertility in different regions of Iran was reported to vary, with an estimate of 23.81% in Guilan Province [6]. Infertility is considered a global health issue with physical, psychological, and social dimensions, and it can even affect interpersonal, social, and marital relationships, threatening individuals’ psychological and social well-being [7, 8].

The social-psychological consequences of female infertility are classified into six main groups: Quality of life (QoL), depression, anxiety, social support, sexual function, and violence [9]. One of the important psychological consequences of infertility for women is violence [10]. Violence against women is considered a major clinical health issue and a violation of women’s human rights, rooted in gender inequalities [11]. Violence has various forms that can come from a spouse (former spouse) or partner and differ in frequency and severity; psychological violence involves the use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the intent to cause mental or emotional harm; physical violence occurs when an individual uses hitting, kicking, or physical force to try to harm their partner; sexual violence involves coercion or attempts to force a partner to engage in a sexual act, sexual contact, or a non-physical sexual event, despite the individual not consenting or being unable to consent [12].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that globally, one in three women experiences physical, psychological, or sexual violence in their lifetime, primarily inflicted by their spouse or partner [13, 14]. In Iran, 71% of women experience violence in the past year [15], including psychological/verbal violence (58%), physical violence (25.2%), and sexual violence (10%)[16]. Iranian pregnant women also experience partner violence at a rate of 48.5%, which is mainly emotional violence (45.5%) [17]. The prevalence of domestic violence in Iran against infertile women varies from 14 to 88% [18]; and violence against infertile women in three dimensions—psychological (52.4%), physical (34%), and sexual (27.2%)—has been higher compared to fertile women [19]. Since infertile women are at risk of violence, they need social support; this improves the life satisfaction of infertile women and, by reducing anxiety, depression, negative self-perception, and hostility, increases their resilience, especially during infertility treatment. Therefore, attention to social support in women’s infertility is impactful and important [10, 20, 21]. Social support means providing material and emotional support from close ones to an individual who is exposed to stressful or difficult conditions [22]. With increased support from spouses, the incidence of postpartum depression in women decreases [23]. There is also a significant positive correlation between perceived social support (from family, friends, and significant others) and adaptation to infertility and QoL [24]. With increasing age and marriage age, perceived social support in infertile women also increases [25].

In some studies, infertile women and those who conceal their infertility have been reported to have lower perceived social support from significant others (spouse or partner) [26-31]. However, in another study, perceived social support was reported to be higher in infertile women than in fertile women [32]. Considering the contradictions in the results of some studies conducted in this regard, as well as the higher prevalence of infertility and cultural and social differences in Iran, the present study aims to determine and compare perceived social support and domestic violence among fertile and infertile women in northern Iran.

Materials and Methods

This is a case-control study conducted on 344 eligible women who were selected using a convenience sampling method from among those visited two infertility treatment and gynecology clinics of Al-Zahra Hospital in Rasht, north of Iran, in 2021. The sample size was first obtained as 130 per group based on the formula, considering the type I error (α) of 0.05, the type II error (β) of 0.2, and an effect size (d) of 0.35. Then, considering a 15% sample dropout and to increase the accuracy of the results, the sample size increased to 172 in each group. The inclusion criteria for fertile women were history of at least one pregnancy, having at least one child, no previous or current history of infertility, and no pregnancy at the time of the study. The inclusion criteria for infertile women were the confirmation of infertility by a gynecologist and having an infertility file. The general inclusion criteria for both groups were the literacy to answer questions, being Iranian, being able to understand and speak Persian, living with a spouse, no chronic heart or lung diseases, blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, no medication use, and no mental disorders (based on self-report or medical file), and willingness to participate in the study and complete the questionnaires. During the study period, 775 women referred to the infertility treatment clinic and 3430 women to the gynecology clinic, of whom 442 were eligible to participate in the study. Finally, 344 eligible women were included, 172 infertile women as the case group and 172 fertile women as controls.

The instruments included a sociodemographic/fertility profile form, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), and the domestic violence sale. The sociodemographic/fertility profile form surveys age, education and occupation of the woman, education and occupation of the husbands, family income status, number of marriages, age at marriage, duration of marriage, place of residence, living with the husband’s family, cause of infertility, duration of infertility, number of infertility treatments, number of infertility treatment failures, and type of infertility (primary and secondary). The domestic violence sale adapted from the WHO violence against women instrument and the Hurt-Insult-Threaten-Scream (HITS) domestic violence screening tool [33, 34] that was developed by Azadarmaki et al. [35]. This tool is a 20-item, self reported questionnaire with three Components: Psychological (7 items), Physical (9 items), and Sexual (4 items). The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (never=0, rarely=1, sometimes=2, often=3, and always=4). The total score ranges from 0 to 80, with higher scores indicating higher levels of domestic violence [35]. The MSPSS is a 12-item tool developed by Zimet et al. [36] that measures perceived social support in three domains: Family, friends, and significant other (spouse or partner). Each domain has 4 items that are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, no opinion, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree). The total score ranges from 12 to 84, with higher scores indicating greater social support. The Persian version of this tool has been validated by Bagherian-Sararoudi et al. [37].

After receiving the introduction letter and obtaining permission, the researcher visited the clinics in Rasht to collect data twice in the morning and evening shifts. After explaining the study objectives and methods, and emphasizing the confidentiality of the data, written informed consent was obtained from the participants, and the questionnaires were completed. After collecting the data, they were analyzed in SPSS software, version 16 using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and multiple linear regression analysis, considering a significance level of P<0.05.

Results

The mean age, age at marriage, and duration of marriage of fertile and infertile women were 35.43±6.2, 34.47±5.88, 19.95±4.16, 25.68±7.32, 14.95±6.52, and 8.67±5.55 years, respectively. The sociodemographic/fertility characteristics of the women are presented in Table 1.

The findings showed that 51.7% of fertile women had two or more children and 88.4% of infertile women had no children. Based on the chi-square test and independent t-test results, there was a statistically significant difference in the variables of age at marriage (P=0.001), duration of marriage (P=0.001), women’s education (P=0.001), spouse’s education (P=0.001), and number of children (P=0.001) between the two groups of fertile and infertile women. However, no statistically significant difference was observed in other sociodemographic/fertility variables. The Mann-Whitney U test results (Table 2) showed no statistically significant difference in the total MSPSS score and in the dimensions of friends and significant other between fertile and infertile women, but the family dimension score was significantly higher in infertile women than in fertile women (P=0.045).

After controlling for sociodemographic/fertility variables using multiple linear regression analysis, the results showed no significant association of the total score and the dimensions of MSPSS with fertility/infertility (Table 3).

The Mann-Whitney U test results (Table 4) showed that the total score of domestic violence in infertile women was significantly lower than in fertile women (P=0.001).

The scores of psychological (P=0.001), physical (P=0.001), and sexual (P=0.013) dimensions were also significantly lower in infertile women. After controlling for sociodemographic/fertility variables using multiple linear regression analysis, the results showed no significant association of the total score and the dimensions of domestic violence with fertility/infertility (Table 5).

According to the regression coefficients, in fertile women, only family income level (P=0.008, b=-6.43) had a statistically significant relationship with perceived social support, while in infertile women, family income status (P=0.034, b=-6.18) and women’s occupation (P=0.008, b=14.58) had a statistically significant relationship with perceived social support. There was a statistically significant relationship between the total score of domestic violence and age at marriage (P=0.004, b=-1.28), husband’s education (P=0.002, b=-7.66), and place of residence (P=0.031, b=-5.44) in fertile women, while the total score of domestic violence in infertile women had a statistically significant relationship only with family income level (P=0.001, b=5.71) (Tables 6 and 7).

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that although the total score of domestic violence in infertile women was lower in fertile women, the difference was not statistically significant, which is in line with the results of Ghoneim et al. [38], while a study showed that the rate of sexual violence in infertile women was significantly higher than in fertile women [39]. Also, the results of the present study are against the results of some other studies [40, 41], which may be due to the lower age of infertile women and the difference in infertility duration, place of residence, living arrangement, educational level of the husbands of infertile women, the used instrument, and sample size.

The total domestic violence score of fertile women showed a significant decrease with the increase of age at marriage. A study [42] showed that employed or high-income people had less intimate partner violence. The results of another study [43] showed that as women’s age increases, the rate of domestic violence against them decreases. The results of the present study are not consistent with their results, which can be due to the sample size and the data collection method.

The total score of domestic violence in infertile women had a statistically significant relationship only with income status. The results of a study found the score of domestic violence was directly related to the duration of infertility, duration of marriage, and duration of infertility treatment, and indirectly related to the age at marriage [44]. However, the results of another study showed that the score of domestic violence was lower in women with high school education than in women with university education [39]. This difference may be due to the difference in the age of women, the type of infertility (primary or secondary), or the instrument used in the study.

According to the results of the present study, there was no statistically significant difference in the total score of perceived social support and its domains between fertile and infertile women, which is consistent with the results of Navid et al. [45], while is against the results of other studies [46, 47], perhaps due to difference in the instrument and sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

Perceived social support was not a relevant variable for domestic violence against either fertile or infertile women.The results of a study [48] showed that, in fertile women, there was a positive and significant correlation between perceived social support in the domains of family and significant other and marital satisfaction of couples. Another study reported a positive and significant correlation between perceived social support and life satisfaction in pregnant women [49], which indicates that perceived social support plays a fundamental role in women’s lives.The results of a study showed that social support was higher in infertile women than in fertile women [33], but fertile women experienced more violence. Differences in the instruments used to measure social support and violence, the unreliability of data collection using an online method, less racial diversity (most participants were white and highly educated), and limited access to the Internet may be reasons for the inconsistency of the results of the present study with those of the mentioned study.

Overall, it can be said that domestic violence is less common in Iranian infertile women than in fertile peers, and Perceived social support was not a relevant variable for domestic violence against either fertile or infertile women. In this study, the family income level of 47.1% of infertile women was not sufficient, therefore it is suggested that governmental and private organizations take actions to support or provide financial facilities to infertile couples. It is also recommended that healthcare providers, as physical and psychological supporters of infertile/fertile women, assess and identify the factors that can be effective in preventing, occurring, reducing, or increasing domestic violence and perceived social support, in order to increase perceived social support and reduce domestic violence among these women.

One of the limitations of this study was the possibility of women’s biased responses to questions related to domestic violence due to cultural, social issues, or shame. Other limitations were the lack of follow-up due to economic issues or refusal of the spouse to seek infertility treatment. Also, these results may not be generalizable to all women in Iran, since data were collected from only one teaching-treatment center in north of Iran. Since the allocation in this study was not done randomly, there is a risk of selection bias. It is recommended that future research, considering data collection from multiple centers, assess the impact of social desirability responding bias on the validity of the results. Also, given the cross-sectional design of the present study, future observational (cohort) studies should be conducted to more accurately examine the outcomes.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC. 2018.34). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after describing the study objectives. They were free to leave the study at any time.

Funding

This article was extracted from a research project and financially supported by Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Methodology and data analysis: Saman Maroufizadeh; Data collection: Nadia Nasiri; Writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants and the staff of the infertility treatment and gynecology clinics of Al-Zahra Hospital, Rasht, Iran.

References

- asrm. Advancing reproductive medicine [Internet]. 2020 [Updated 2020 December 27]. [Link]

- Pizzorno JE, Murray MT. Textbook of natural medicine-e-book. Edinburgh: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2020. [Link]

- Vander Borght M, Wyns C. Fertility and infertility: Definition and epidemiology. Clin Biochem. 2018; 62:2-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.012] [PMID]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assisted reproductive technology (art), infertility, reproductive health USA 2015 [Internet]. 2018 [updated 2018 May 5]. Available from: [Link]

- Saei Ghare Naz M, Ozgoli G, Sayehmiri K. Prevalence of infertility in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol J. 2020; 17(4):338-45. [DOI:10.22037/uj.v17i4.5610]

- Akhondi MM, Ranjbar F, Shirzad M, Ardakani ZB, Kamali K, Mohammad K. Practical difficulties in estimating the prevalence of primary infertility in Iran. Int J Fertil Steril. 2019; 13(2):113. [PMID]

- Yari T, Ghorbani B, Alamin S. [Infertility and lack of sense of security in marital life (Persian)]. J Soc Order. 2019; 11(3):67-92. [Link]

- Aghakhani N, Marianne Ewalds-Kvist B, Sheikhan F, Merghati Khoei E. Iranian women's experiences of infertility: A qualitative study. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2020; 18(1):65-72. [DOI:10.18502/ijrm.v18i1.6203] [PMID]

- Zarif Golbar Yazdi H, Aghamohammadian Sharbaf H, Kareshki H, Amirian M. Infertility and psychological and social health of iranian infertile women: A systematic review. Iran J Psychiatry. 2020; 15(1):67-79. [PMID]

- Zarif Golbar Yazdi H, Aghamohammadian Sharbaf H, Kareshki H, Amirian M. Psychosocial consequences of female infertility in Iran: A meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020; 11:518961. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.518961] [PMID]

- WHO. Violence against women 2021 [Internet]. 2021 [Updated 2024 March 25]. Available from: [Link]

- Sleet D, Ying C, Sauber-Schatz E. Injury prevention at the US-centers for disease control and prevention. Inj Med. 2015;4(2):44-53. [PMID]

- WHO. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018 [Internet]. 2021 [Updated 2021 March 9]. Available from: [Link]

- WHO. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence [Internet]. 2013 [Updated 2013 October 20]. Available from: [Link]

- Afkhamzadeh A, Azadi NA, Ziaeei S, Mohamadi-Bolbanabad A. Domestic violence against women in west of Iran: The prevalence and related factors. Int J Hum Rights Healthc. 2019; 12(5):364-72. [DOI:10.1108/IJHRH-12-2018-0080]

- Sheikhbardsiri H, Raeisi A, Khademipour G. Domestic violence against women working in four educational hospitals in Iran. J Interpers Violence. 2020; 35(21-22):5107-21. [DOI:10.1177/0886260517719539] [PMID]

- Sobhani S, Niknami M, Mirhaghjou SN, Atrkar Roshan Z. Domestic violence and its maternal and fetal consequences among pregnant women. J Holistic Nurs Midwifery. 2018; 28(2):143-9. [DOI:10.29252/hnmj.28.2.143]

- Sharifi F, Jamali J, Larki M, Roudsari RL. Domestic violence against infertile women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2022; 22(1):14-27. [DOI:10.18295/squmj.5.2021.075] [PMID]

- Poornowrooz N, Jamali S, Haghbeen M, Javadpour S, Sharifi N, Mosallanezhad Z. The comparison of violence and sexual function between fertile and infertile women: A study from Iran. J Clin Diagn Res. 2019;13(1). [DOI:10.7860/JCDR/2019/37993.12516]

- Chu X, Geng Y, Zhang R, Guo W. Perceived social support and life satisfaction in infertile women undergoing treatment: A moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. 2021; 12:651612. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.651612] [PMID]

- Avşar B, EMUL TG. The relationship between social support perceived by infertile couples and their mental status. 2021 [Unpublished]. [DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-487754/v1]

- Nausheen B, Gidron Y, Peveler R, Moss-Morris R. Social support and cancer progression: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2009; 67(5):403-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.12.012] [PMID]

- Hajipoor S, Pakseresht S, Niknami M, Atrkar Roshan Z, Nikandish S. The relationship between social support and postpartum depression. J Holist Nurs Midwifery. 2021; 31(2):93-103. [DOI:10.32598/jhnm.31.2.1099]

- Seo-yoon I. The impact of Infertility stress and social support on the Quality of Life for infertile women [PhD dissertation]. Suwon-si: Ajou University Hospital; 2021. [Link]

- Hasanpour Dehkordi A, Ganji F, Kaveh Baghbahadrani F, Omidi M. [Assessment of perceived social support and its related factors in infertile women referring to Shahrekord Infertility Clinic (Persian)]. J Clin Nurs Midwifery. 2020; 9(2):666-77. [Link]

- Ozan YD, Duman M. Relationships between the perceived social support and adjustment to infertility in women with unsuccessful infertility treatments, Turkey-2017. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2020; 7(2):99-104. [DOI:10.4103/JNMS.JNMS_50_19]

- Ataman H, Aygun O, Pekcan N, Merih YD. The relationship between the perceived social support levels and levels of adjustment to the infertility problem of women who received infertility treatment. Izmir Democracy Univ Health Sci J. 2021; 4(3):285-301. [DOI:10.52538/iduhes.1025934]

- Saleem S, Qureshi NS, Mahmood Z. Attachment, perceived social support and mental health problems in women with primary infertility. Int J Reproduction, Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 8(6):2533. [DOI:10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20192463]

- Khadim R, Naeem F, Saleem S, Mahmood Z. Perceived social support and mental health problems in infertile women: A comparative study. Rawal Med J. 2019; 44(3):584-7. [DOI:10.35845/kmuj.2021.21373]

- Amini L, Ghorbani B, Sadeghi AvvalShahr H, Raoofi Z, Mortezapour Alisaraie M. [The relationship between percieved social support and infertility stress in wives of infertile men (Persian)]. Iran J Nurs. 2018; 31(111):31-9. [DOI:10.29252/ijn.31.111.31]

- Yazdani F, Kazemi A, Fooladi MM, Samani HR. The relations between marital quality, social support, social acceptance and coping strategies among the infertile Iranian couples. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016; 200:58-62. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.02.034] [PMID]

- Öztürk R, Bloom TL, Li Y, Bullock LFC. Stress, stigma, violence experiences and social support of US infertile women. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2021; 39(2):205-17. [DOI:10.1080/02646838.2020.1754373] [PMID]

- Nybergh L, Taft C, Krantz G. Psychometric properties of the WHO violence against women instrument in a female population-based sample in Sweden: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2013; 3(5):e002053. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002053] [PMID]

- Shakil A, Donald S, Sinacore JM, Krepcho M. Validation of the HITS domestic violence screening tool with males. Fam Med. 2005; 37(3):193-8. [PMID]

- Azadarmaki T, Kassani A, Menati R, Hassanzadeh J, Menati W. Psychometric properties of a screening instrument for domestic violence in a sample of Iranian women. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2016; 5(1):e27763. [DOI:10.17795/nmsjournal27763] [PMID]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988; 52(1):30-41. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2]

- Bagherian-Sararoudi R, Hajian A, Ehsan HB, Sarafraz MR, Zimet GD. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2013; 4(11):1277-81. [PMID]

- Ghoneim HM, Taha OT, Ibrahim ZM, Ahmed AA. Violence and sexual dysfunction among infertile Egyptian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021; 47(4):1572-8. [DOI:10.1111/jog.14689] [PMID]

- Rahebi SM, Rahnavardi M, Rezaie-Chamani S, Nazari M, Sabetghadam S. Relationship between domestic violence and infertility. East Mediterr Health J. 2019; 25(8):537-42. [DOI:10.26719/emhj.19.001] [PMID]

- Akyuz A, Seven M, Sahiner G, Bilal B. Studying the effect of infertility on marital violence in Turkish women. Int J Fertil Steril. 2013 Jan; 6(4):286-93. [PMID]

- Akpinar F, Yilmaz S, Karahanoglu E, Ozelci R, Coskun B, Dilbaz B, et al. Intimate partner violence in Turkey among women with female infertility. Sex Relat Ther. 2019; 34(1):3-9. [DOI:10.1080/14681994.2017.1327711]

- Schneider D, Harknett K, McLanahan S. Intimate partner violence in the great recession. Demography. 2016; 53(2):471-505. [DOI:10.1007/s13524-016-0462-1] [PMID]

- Castro RJ, Cerellino LP, Rivera R. Risk factors of violence against women in Peru. J Fam Violence. 2017; 32(8):807-15. [DOI:10.1007/s10896-017-9929-0]

- Omidi K, Pakseresht S, Niknami M, Kazem Nezhad Leilie E, Salimi Kivi M. Violence and its related factors in infertile women attending infertility centers: A cross-sectional study. J Midwifery Reproduct Health. 2021; 9(4):2988-98. [DOI:10.22038/jmrh.2021.58462.1708]

- Navid B, Mohammadi M, Sasannejad R, Aliakbari Dehkordi M, Maroufizadeh S, Hafezi M, et al. Marital satisfaction and social support in infertile women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2018; 23(4):450-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.mefs.2018.01.014]

- Jamilian H, Jamilian M, Soltany S. The comparison of quality of life and social support among fertile and infertile women. J Patient Saf Qual Improv. 2017; 5(2):521-5. [DOI:10.22038/psj.2017.12370.1111]

- Martins MV, Peterson BD, Almeida VM, Costa ME. Direct and indirect effects of perceived social support on women's infertility-related stress. Hum Reprod. 2011; 26(8):2113-21. [DOI:10.1093/humrep/der157] [PMID]

- Sultan A, Yousuf S, Jan S, Hassan U, Jaan U. Assesing perceived social support and marital satisfaction among fertile and infertile women. Age. 2018; 20(30):55-71. [Link]

- Yu M, Qiu T, Liu C, Cui Q, Wu H. The mediating role of perceived social support between anxiety symptoms and life satisfaction in pregnant women: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020; 18(1):223. [DOI:10.1186/s12955-020-01479-w] [PMID]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2022/05/24 | Accepted: 2023/02/14 | Published: 2025/09/8

Received: 2022/05/24 | Accepted: 2023/02/14 | Published: 2025/09/8

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |