Fri, Apr 26, 2024

Volume 32, Issue 1 (1-2022)

JHNM 2022, 32(1): 58-68 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Jelly P, K Sharma S, Saxena V, Arora G, Sharma R. Exploration of Breastfeeding Practices in India: A Systematic Review. JHNM 2022; 32 (1) :58-68

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-1793-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-1793-en.html

1- College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, India. , prasunajelly@gmail.com

2- College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

3- Department of Community and Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, India.

4- College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, India.

2- College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

3- Department of Community and Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, India.

4- College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, India.

Full-Text [PDF 647 kb]

(1019 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1164 Views)

Full-Text: (795 Views)

Introduction

To make a country's population healthier, breastfeeding is one of the intelligent investments done by any government [1]. Breastfeeding is safe, available, affordable, and ensures the child's health, especially in developing countries [2]. Breastfeeding not only protects children from a bunch of ailments but also increases their Intelligence Quotient (IQ) and creates a strong connection between mother and baby [1].

The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have suggested that all mothers should nurture their children exclusively with breastfeeding for four months to half a year and keep breastfeeding enhanced by other proper nourishments to the second year of life or later [3].

Despite having proven benefits, breastfeeding has remained a less than desirable practice, especially in a developing country like India. A considerable increase has been made in India in the paces of institutional conveyances from 38.7% (National Family Health Survey, NFHS-3) to 78.9% (NFHS-4) during a range of ten years. Still, almost half (45.1%) of the children below six months of age are not solely breastfed [4]. NFHS-4 likewise shows that 21% of infants get prelacteal feeds, and about 22% are brought into the world with low birth weight, who need additional help [4]. Prelacteal feeds are common practice in India, especially in rural areas [5]. In India, many institutional deliveries happen in private hospitals, and infant formula is a common practice in these hospitals [6].

India, along with other South Asian countries, including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, stands at the lowest position in breastfeeding practice, with just 44% of women desiring to breastfeed their child within one hour of birth [7, 8]. There has been an improvement in India's breastfeeding status over decades because of promoting strategies, powerful building initiatives, ground level-based activities, and strategic mass media communication [9].

Breastfeeding in rural areas in India tends to be shaped by community beliefs, which are often influenced by social, cultural, and economic factors [10]. At the same time, a rapid increase in the proportion of people living in built-up areas and the social, cultural, and economic changes associated with this urbanization process can impact traditional breastfeeding practices [11]. However, regarding the significance of breastfeeding, it is surprising that the study of breastfeeding practices in India has remained ignored. No substantial attempts have been made to document the breastfeeding practices in different parts of India, the effect of urbanization and modernization on feeding practices, or the connection between fertility and lactation [12].

Although several studies have been conducted on this subject, no systematic review has summarised these findings. Hence, the following questions emerged as what practices mothers follow on early initiation of breastfeeding, prelacteal feed, Exclusive Breastfeeding (EBF) in the first six months of life, and weaning of an infant. Therefore, the present study has been conducted to systematically review literature exclusively from India to get an orientation of breastfeeding aspects, various programs to promote EBF introduced by the Government of India, and improved literacy rate in India from the past twenty years.

Materials and Methods

A systematic review was conducted by searching the published literature in PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Google Scholar, Clinical key, Cochrane library, and Science Direct databases through electronic media to identify the breastfeeding practices during the first six months of life of an infant. We used free-text and MeSH terms like “breastfeeding practices”, “postpartum beliefs”, “weaning practices”, “infant and young child feeding practices”, and “India” for searching the literature. Studies published from 2001 to December 2020 were included in this review. Hand searching and screening were done for the reference list of included studies.

The inclusion criteria were studies conducted in India, studies reporting early initiation of breastfeeding practices and related factors by using non-experimental descriptive and mixed-method study designs, using of prelacteal feed, EBF practices, studied weaning practices, and lactating mothers as study participants, regardless of the number of children and mode of delivery. We excluded content from books, unpublished theses/dissertations, unpublished case reports, and conferences.

All the studies were selected by skimming titles and abstracts to find potentially valid citations by three reviewers independently. Full texts of all potentially relevant papers were retrieved and evaluated for eligibility based on the predefined inclusion criteria independently by reviewers. The study data were extracted from the selected studies. Any disagreements and discrepancies among reviewers were resolved by discussion and consulting the fourth and fifth authors. Study characteristics and breastfeeding practices in India’s rural and urban parts were extracted in the pre-designed datasheet. Each reviewer independently extracted the data, and discrepancies were resolved if found.

The outcomes of this study were early initiation of breastfeeding and related factors, exploring the use of prelacteal feed, EBF, and weaning practices.

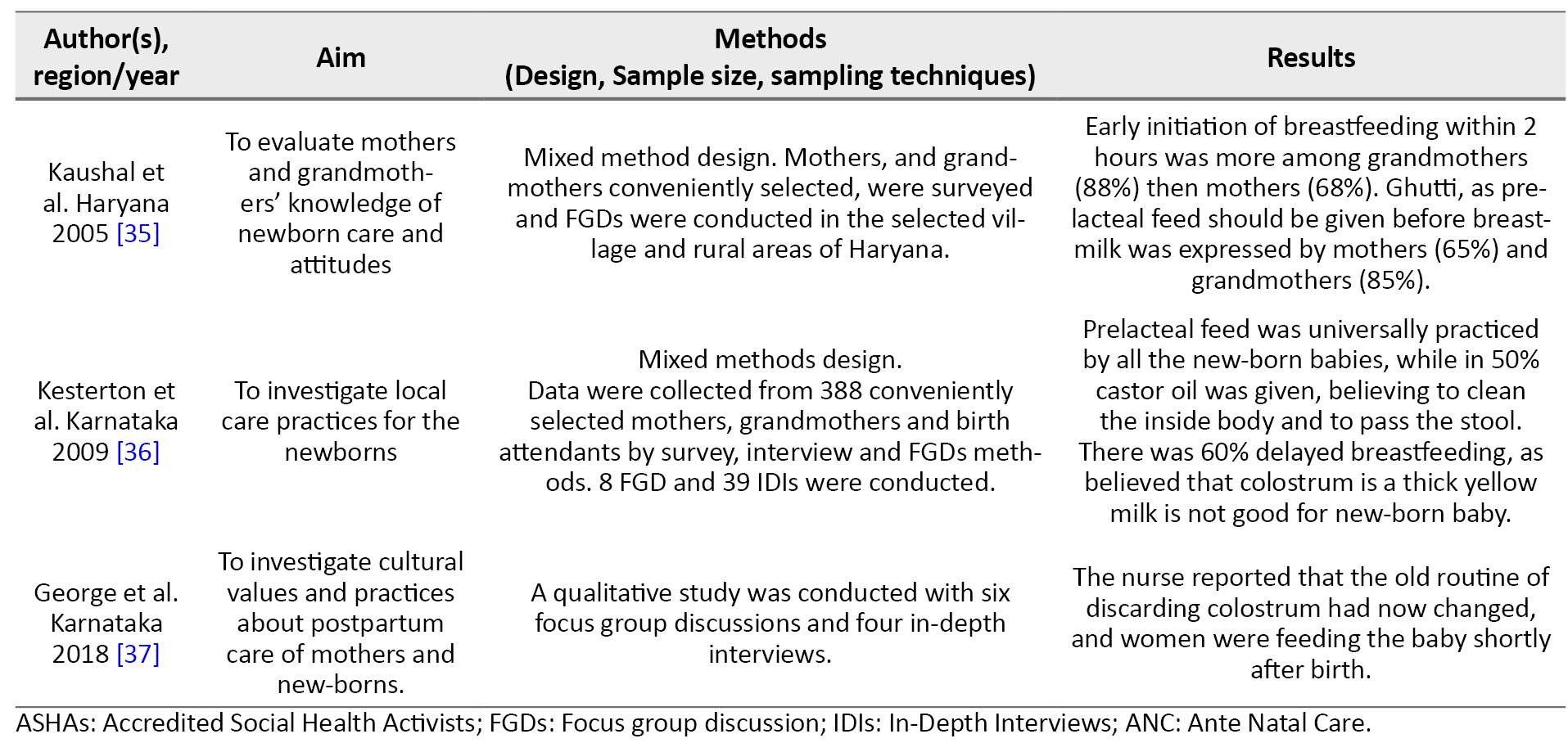

Two reviewers assessed the quality of included studies by adopting the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for observational studies quality assessment tool [13]. All t studies were included in the review, and the result of quality assessment scores and details are mentioned in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

.png)

.png)

.png)

Results

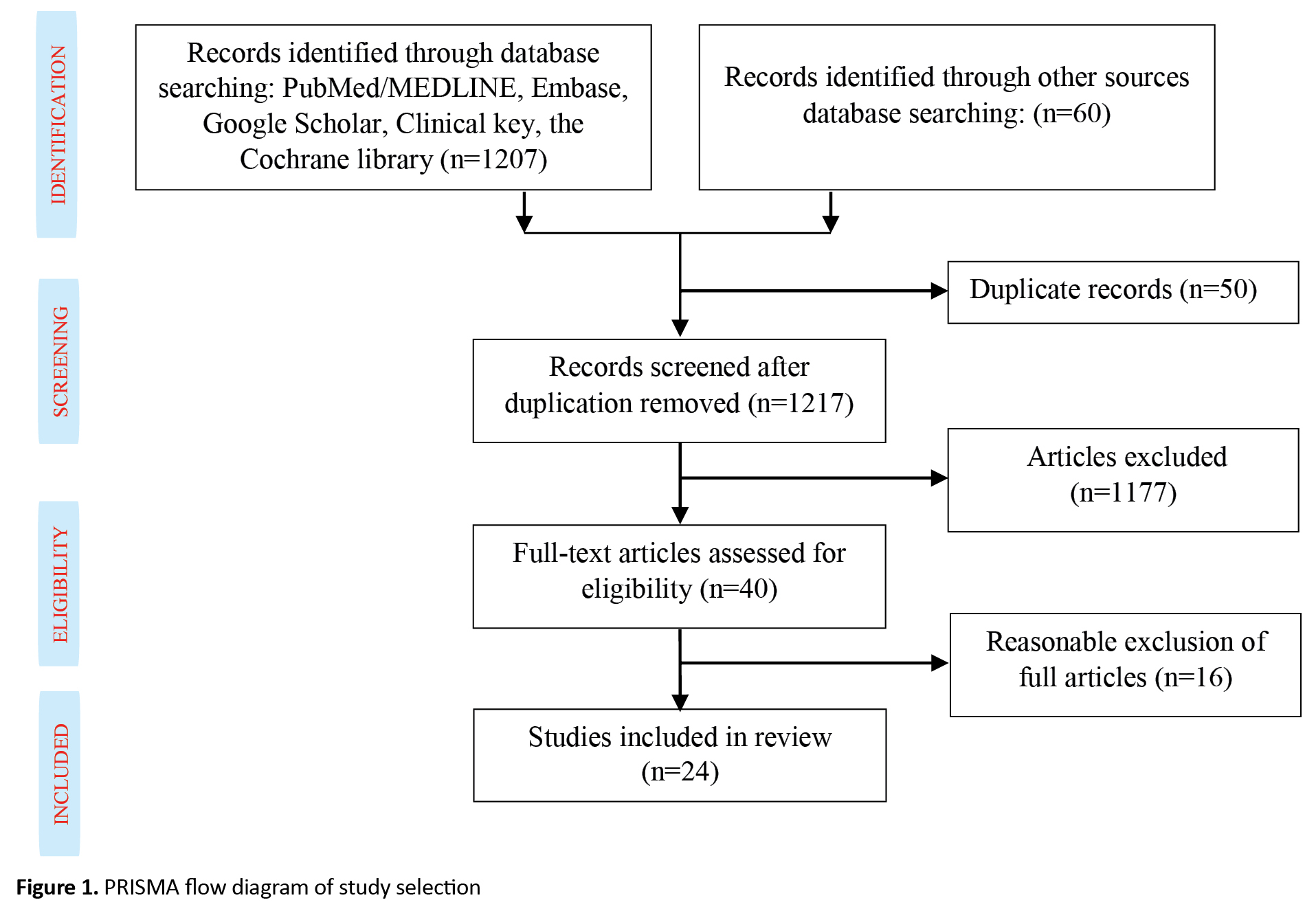

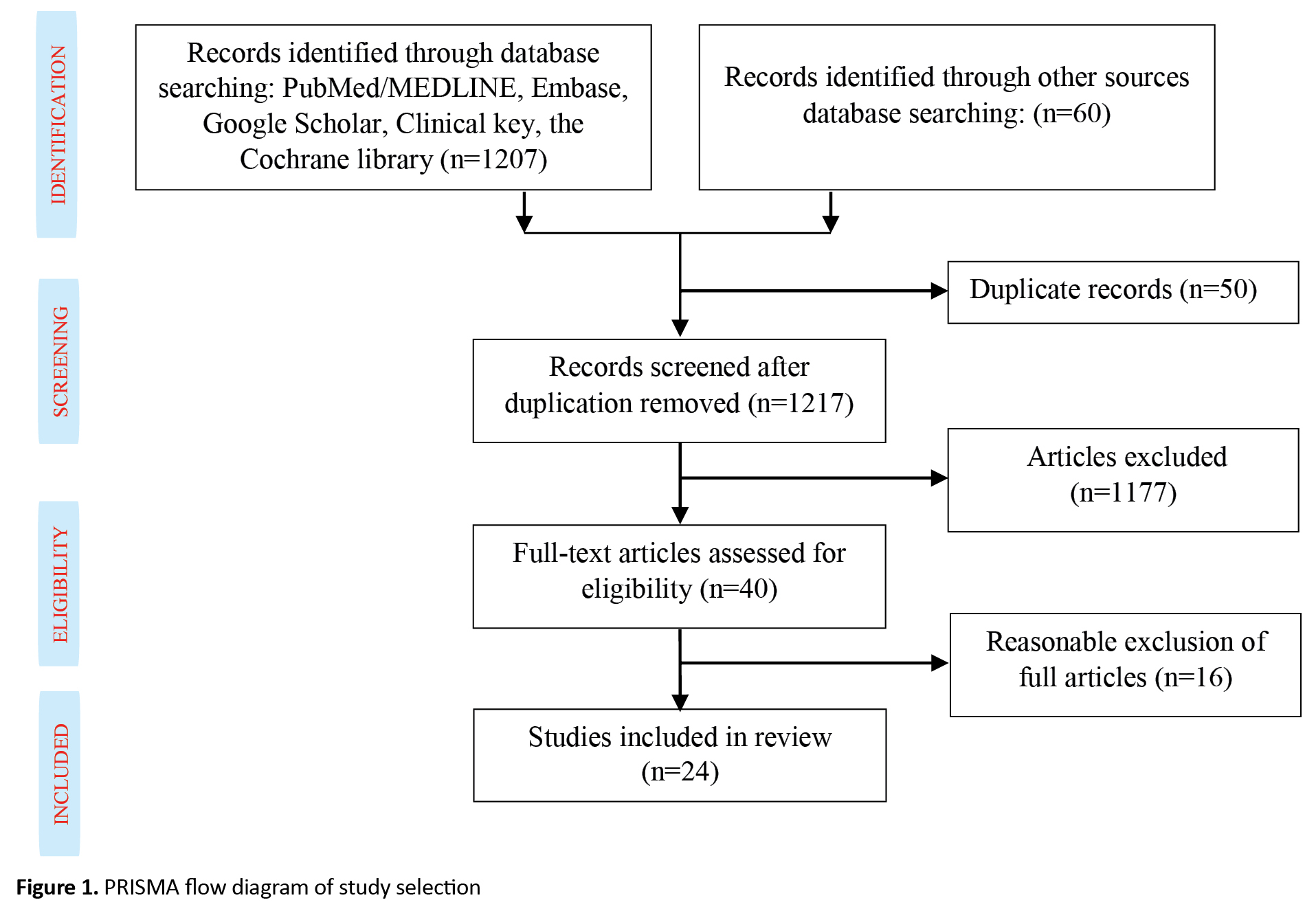

Study selection was performed according to the PRISMA (The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines for search and selection of studies and the inclusion criteria. A total of 1267 studies were retrieved from electronic databases, of which 50 were duplicates due to different databases (Figure 1).

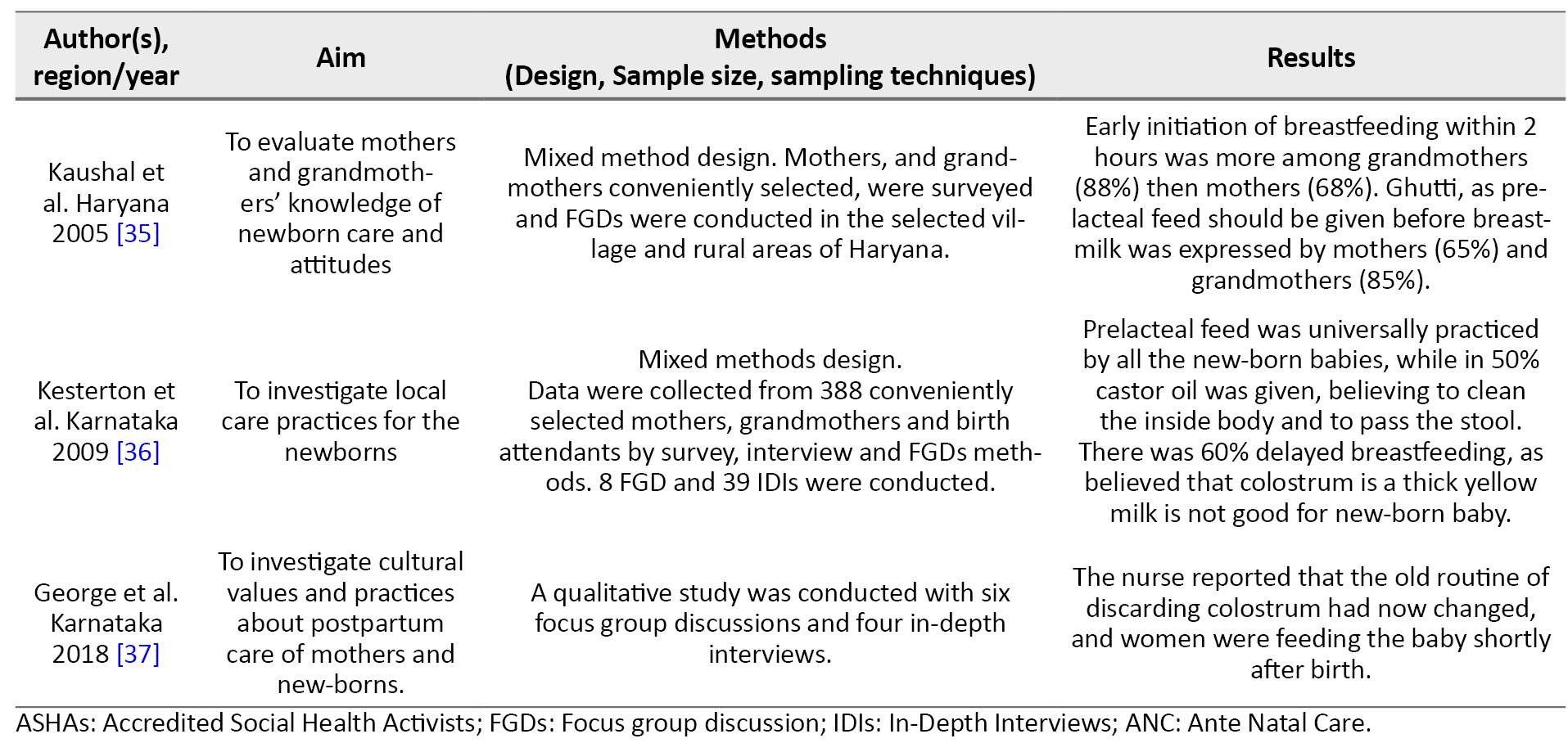

The remaining 1217 paper titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, and 1177 were irrelevant and omitted. Furthermore, full-text papers were reviewed for eligibility and based on the pre-specified inclusion criteria, 24 studies were included for systematic review, which was published between 2001 to 2020 from different regions of India (Table 4).

.png)

.png)

Out of 24 selected studies, most articles were cross-sectional [5, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32] Aligarh has a population of 40,000 living in 5,480 households. Mothers delivering babies in September 2007 were identified from records of social mobilization workers Community Mobilization Coordinators or (CMCs), and others had had qualitative cohort or mix method design.

Most studies reported that initiation of breastfeeding was within 1-6 hours after the delivery. In seven studies, many participants had initiated breastfeeding within one hour of newborn’s life [15, 24, 25, 27, 29, 30, 33]. In contrast, few participants in another study [15] reported delayed breastfeeding initiation; the quoted reasons were baby separation as the commonest reason (45%), followed by mother's illness (27.3%). For 24.7% of mothers, breast milk was not secreted, and 3% were ignorant about timely initiation. Kaushal et al. observed that the majority of grandmothers (62%) believed in delaying breastfeeding until six hours after delivery, while few mothers (20%) believed in that [34]. It was also reported that they believe newborn has impure things in the stomach, so for two to three days, the baby was given oil and other foods than mothers' milk [35]. A study highlighted the initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of delivery in 40.5% of mothers. However, in 27.6% of cases, the mother's maternal surgery was the most common reason for the delay of breastfeeding initiation [30].

Various prelacteal feeds were given to newborns included beverages such as tea, boiled water, honey, sugar water, jaggery (a coarse brown sugar made from palm sap), glucose with plain water, diluted animal milk, tinned milk, ghee, and castor oil. Madhu et al. stated that 13% of the babies are fed for more than 48 hours of sugar water alone. Also, honey (6%) and ghee (3%) were widely used as prelacteal feeds [25]. About 62% of mothers practiced EBF, and 28.2% discarded colostrum. The most common explanations for discarding colostrum were the mother’s belief that it was not safe for the baby (19.77%), unhygienic (17.44%), social norms (8.14%), and other reasons (11.63%) [30].

EBF is suboptimally practiced and often continued for less than 4-6 months. Few mothers (30.2%) practiced formula feeding, and insufficient milk was the primary (44.5%) reason for starting formula feeding compared to mothers in the slum area (20.39%). Almost 61.84% of the babies were given breastfeeding during illness [30]. Weaning practices were primarily started at 4-5 months of life, and there were several reasons reported for the early initiation of the weaning practices, the most common was insufficient milk (92%; 49 out of 53). On-demand feeding practices and rooming-in were followed by 84% of mothers. The commonest food for breastfed infants for less than 6 months was cow’s milk (26%) [25].

In a study conducted by Bhanderi et al. [20], cow’s milk was used for top feeding, whereas rice and “daal” as weaning food. Kaushal et al. analysis revealed that 34% of mothers and 25% of grandmothers adopted complementary feeding at 4-6 months of age. About 41% of mothers and 34% of grandmothers used “Dalia” and “Khichdi” as complementary foods. However, most respondents (59% mothers and 66% grandmothers) said that they were not sure when to begin weaning and with what semi-solids [34] using a triangulation of qualitative (focus group discussion.

In conclusion, the time of initiation of breastfeeding was within 1-6 hours after birth, and various prelacteal feeds were given to newborns, including beverages such as tea, boiled water, honey, sugar water, jaggery, or glucose with plain water, diluted animal milk, tinned milk, ghee, castor oil. Weaning practices were primarily started at 4-5 months of life. Whereas EBF remains less than desirable, and suboptimal weaning practices have led to suboptimal growth of an infant.

Discussion

The early introduction of breastfeeding, EBF for half a year, and the prompt implementation of age-appropriate complementary feeding are the key mediations for achieving the Millennium Development Goals 1 and 4 that address the infant malnutrition aspect of the goals and mortality, respectively [16] cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted during June-July 2008 to assess the infant-and young child-feeding (IYCF. To understand the measures to reduce Neonatal Mortality Rate (NMR), we should know optimal breastfeeding practices followed in different regions of India. The present review emphasized the breastfeeding practices followed in rural and urban Indian population.

Our results were inferred from 24 studies on the various aspects of breastfeeding practice in different regions of India. Early breastfeeding initiation has survival benefits and also decreases neonatal mortality [37]. Consistent with the above findings from the systematic review [14, 15, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 32, 33, 35] Aligarh has a population of 40,000 living in 5,480 households. Mothers delivering babies in September 2007 were identified from records of social mobilization workers (Community Mobilization Coordinators or CMCs, early initiation of breastfeeding is in practice so that NMR has declined to 23.5 as compared to 38 in 2019. Contrary to the above findings, some studies have shown delayed breastfeeding initiation due to cultural beliefs, less amount of breast milk, too tired to feed, baby sleep, cesarean section, and lack of awareness. These are some of the mentioned reasons for delayed breastfeeding practice, particularly in rural versus urban populations [15, 18, 26, 34, 36] using a triangulation of qualitative (focus group discussion.

Prelacteal feeds are those foods given to newborns before initiating breastfeeding or before breast milk “comes in”, usually on the first day of life [38]. Because of cultural diversity, the Indian population emphasizes the rural area and still practice prelacteal feeding. The common prelacteal feeds were honey, “ghutti”, sugar, and tea [34, 36] using a triangulation of qualitative (focus group discussion. Not only among mothers and family but this belief is also followed among health providers Anxiety Nurse Midwife (ANM) in a rural setting has proclaimed that despite the change in guidelines, prelacteal feed is still recommended [36]. Reddy et al. highlighted the use of honey [35], risk factors, and interactions of enteric infections and malnutrition and the consequences for child health. Khan et al. cited family customs and relatives’ advice for prelacteal feed [14].

As per WHO, EBF means giving the baby only breast milk for the first 6 months without adding any additional drink, including water or food [39]. Despite the undeniable benefits of EBF, its practice has remained less than desirable. According to Kaushal et al., less than 10% of the study population followed the EBF [34]. In contrast, a study revealed that participants started the weaning practice in less than 4 months and followed the on-demand feeding [15]. Studies from different parts of India have found that the EBF practice was not followed by mothers [17, 18, 21, 25]. Saxena Y et al. found multiple hindering factors for EBF: inadequate mother's milk, cesarean sections, and coercion from elders in the family to start top milk [40].

Weaning practices are the approach of introducing soft, semi-solid, and or solid foods by six months of age along with breast milk [41]. In India, there is an enormous diversity in different regions to start weaning feed, such as "Dalia", "Khichdi", "ragi sari", cow's milk, and rice. The early weaning hinders the EBF practice [20, 23, 34]. Additionally, inadequate knowledge about weaning and weaning foods were the limiting factors contributing to suboptimal weaning practices leading to suboptimal growth of an infant [34]. Accordingly, the risk for infections, undernutrition, and child morbidity and mortality has been increased [42, 43]. Emphasis should be on assessing proper, regionally available weaning diets and a well-planned regional weaning education, a common element of well-baby programs [44].

This review shows that breastfeeding practice in India is common. However, many breastfeeding and weaning methods are not conducive to the child’s growth and development. The study shows that the early onset of breastfeeding is commonly being practiced, but colostrum is still being discarded. It is necessary to address the myths of prelacteal feed that delay the early initiation of breastfeeding by postnatal mothers. Health care workers, especially nurses, Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM), primary health centers, community health centers, emphasize the importance of early initiation of breastfeeding, EBF, and weaning practices.

We recommend that future researchers perform a meta-analysis to provide higher-level evidence from India. Also, a transcultural study will be appropriate to understand differences in cultural practices, which could hinder the early initiation of breastfeeding, EBF, and weaning process that will help plan different intervention modules according to regional practices. We could not access a few full texts of related articles, which might have added strength to the present review.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Author's contributions

Study concept, literature search: Prasuna Jelly, Rakesh Sharma, and Gunjot Arora; Review and data extraction: Prasuna Jelly, Rakesh Sharma, Gunjot Arora, and Suresh K Sharma; Quality assessment, reviewing the final edition: All authors; Results and discussion: Prasuna Jelly, Rakesh Sharma, and Gunjot Arora.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

To make a country's population healthier, breastfeeding is one of the intelligent investments done by any government [1]. Breastfeeding is safe, available, affordable, and ensures the child's health, especially in developing countries [2]. Breastfeeding not only protects children from a bunch of ailments but also increases their Intelligence Quotient (IQ) and creates a strong connection between mother and baby [1].

The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have suggested that all mothers should nurture their children exclusively with breastfeeding for four months to half a year and keep breastfeeding enhanced by other proper nourishments to the second year of life or later [3].

Despite having proven benefits, breastfeeding has remained a less than desirable practice, especially in a developing country like India. A considerable increase has been made in India in the paces of institutional conveyances from 38.7% (National Family Health Survey, NFHS-3) to 78.9% (NFHS-4) during a range of ten years. Still, almost half (45.1%) of the children below six months of age are not solely breastfed [4]. NFHS-4 likewise shows that 21% of infants get prelacteal feeds, and about 22% are brought into the world with low birth weight, who need additional help [4]. Prelacteal feeds are common practice in India, especially in rural areas [5]. In India, many institutional deliveries happen in private hospitals, and infant formula is a common practice in these hospitals [6].

India, along with other South Asian countries, including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, stands at the lowest position in breastfeeding practice, with just 44% of women desiring to breastfeed their child within one hour of birth [7, 8]. There has been an improvement in India's breastfeeding status over decades because of promoting strategies, powerful building initiatives, ground level-based activities, and strategic mass media communication [9].

Breastfeeding in rural areas in India tends to be shaped by community beliefs, which are often influenced by social, cultural, and economic factors [10]. At the same time, a rapid increase in the proportion of people living in built-up areas and the social, cultural, and economic changes associated with this urbanization process can impact traditional breastfeeding practices [11]. However, regarding the significance of breastfeeding, it is surprising that the study of breastfeeding practices in India has remained ignored. No substantial attempts have been made to document the breastfeeding practices in different parts of India, the effect of urbanization and modernization on feeding practices, or the connection between fertility and lactation [12].

Although several studies have been conducted on this subject, no systematic review has summarised these findings. Hence, the following questions emerged as what practices mothers follow on early initiation of breastfeeding, prelacteal feed, Exclusive Breastfeeding (EBF) in the first six months of life, and weaning of an infant. Therefore, the present study has been conducted to systematically review literature exclusively from India to get an orientation of breastfeeding aspects, various programs to promote EBF introduced by the Government of India, and improved literacy rate in India from the past twenty years.

Materials and Methods

A systematic review was conducted by searching the published literature in PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Google Scholar, Clinical key, Cochrane library, and Science Direct databases through electronic media to identify the breastfeeding practices during the first six months of life of an infant. We used free-text and MeSH terms like “breastfeeding practices”, “postpartum beliefs”, “weaning practices”, “infant and young child feeding practices”, and “India” for searching the literature. Studies published from 2001 to December 2020 were included in this review. Hand searching and screening were done for the reference list of included studies.

The inclusion criteria were studies conducted in India, studies reporting early initiation of breastfeeding practices and related factors by using non-experimental descriptive and mixed-method study designs, using of prelacteal feed, EBF practices, studied weaning practices, and lactating mothers as study participants, regardless of the number of children and mode of delivery. We excluded content from books, unpublished theses/dissertations, unpublished case reports, and conferences.

All the studies were selected by skimming titles and abstracts to find potentially valid citations by three reviewers independently. Full texts of all potentially relevant papers were retrieved and evaluated for eligibility based on the predefined inclusion criteria independently by reviewers. The study data were extracted from the selected studies. Any disagreements and discrepancies among reviewers were resolved by discussion and consulting the fourth and fifth authors. Study characteristics and breastfeeding practices in India’s rural and urban parts were extracted in the pre-designed datasheet. Each reviewer independently extracted the data, and discrepancies were resolved if found.

The outcomes of this study were early initiation of breastfeeding and related factors, exploring the use of prelacteal feed, EBF, and weaning practices.

Two reviewers assessed the quality of included studies by adopting the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for observational studies quality assessment tool [13]. All t studies were included in the review, and the result of quality assessment scores and details are mentioned in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

.png)

.png)

.png)

Results

Study selection was performed according to the PRISMA (The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines for search and selection of studies and the inclusion criteria. A total of 1267 studies were retrieved from electronic databases, of which 50 were duplicates due to different databases (Figure 1).

The remaining 1217 paper titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, and 1177 were irrelevant and omitted. Furthermore, full-text papers were reviewed for eligibility and based on the pre-specified inclusion criteria, 24 studies were included for systematic review, which was published between 2001 to 2020 from different regions of India (Table 4).

.png)

.png)

Out of 24 selected studies, most articles were cross-sectional [5, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32] Aligarh has a population of 40,000 living in 5,480 households. Mothers delivering babies in September 2007 were identified from records of social mobilization workers Community Mobilization Coordinators or (CMCs), and others had had qualitative cohort or mix method design.

Most studies reported that initiation of breastfeeding was within 1-6 hours after the delivery. In seven studies, many participants had initiated breastfeeding within one hour of newborn’s life [15, 24, 25, 27, 29, 30, 33]. In contrast, few participants in another study [15] reported delayed breastfeeding initiation; the quoted reasons were baby separation as the commonest reason (45%), followed by mother's illness (27.3%). For 24.7% of mothers, breast milk was not secreted, and 3% were ignorant about timely initiation. Kaushal et al. observed that the majority of grandmothers (62%) believed in delaying breastfeeding until six hours after delivery, while few mothers (20%) believed in that [34]. It was also reported that they believe newborn has impure things in the stomach, so for two to three days, the baby was given oil and other foods than mothers' milk [35]. A study highlighted the initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of delivery in 40.5% of mothers. However, in 27.6% of cases, the mother's maternal surgery was the most common reason for the delay of breastfeeding initiation [30].

Various prelacteal feeds were given to newborns included beverages such as tea, boiled water, honey, sugar water, jaggery (a coarse brown sugar made from palm sap), glucose with plain water, diluted animal milk, tinned milk, ghee, and castor oil. Madhu et al. stated that 13% of the babies are fed for more than 48 hours of sugar water alone. Also, honey (6%) and ghee (3%) were widely used as prelacteal feeds [25]. About 62% of mothers practiced EBF, and 28.2% discarded colostrum. The most common explanations for discarding colostrum were the mother’s belief that it was not safe for the baby (19.77%), unhygienic (17.44%), social norms (8.14%), and other reasons (11.63%) [30].

EBF is suboptimally practiced and often continued for less than 4-6 months. Few mothers (30.2%) practiced formula feeding, and insufficient milk was the primary (44.5%) reason for starting formula feeding compared to mothers in the slum area (20.39%). Almost 61.84% of the babies were given breastfeeding during illness [30]. Weaning practices were primarily started at 4-5 months of life, and there were several reasons reported for the early initiation of the weaning practices, the most common was insufficient milk (92%; 49 out of 53). On-demand feeding practices and rooming-in were followed by 84% of mothers. The commonest food for breastfed infants for less than 6 months was cow’s milk (26%) [25].

In a study conducted by Bhanderi et al. [20], cow’s milk was used for top feeding, whereas rice and “daal” as weaning food. Kaushal et al. analysis revealed that 34% of mothers and 25% of grandmothers adopted complementary feeding at 4-6 months of age. About 41% of mothers and 34% of grandmothers used “Dalia” and “Khichdi” as complementary foods. However, most respondents (59% mothers and 66% grandmothers) said that they were not sure when to begin weaning and with what semi-solids [34] using a triangulation of qualitative (focus group discussion.

In conclusion, the time of initiation of breastfeeding was within 1-6 hours after birth, and various prelacteal feeds were given to newborns, including beverages such as tea, boiled water, honey, sugar water, jaggery, or glucose with plain water, diluted animal milk, tinned milk, ghee, castor oil. Weaning practices were primarily started at 4-5 months of life. Whereas EBF remains less than desirable, and suboptimal weaning practices have led to suboptimal growth of an infant.

Discussion

The early introduction of breastfeeding, EBF for half a year, and the prompt implementation of age-appropriate complementary feeding are the key mediations for achieving the Millennium Development Goals 1 and 4 that address the infant malnutrition aspect of the goals and mortality, respectively [16] cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted during June-July 2008 to assess the infant-and young child-feeding (IYCF. To understand the measures to reduce Neonatal Mortality Rate (NMR), we should know optimal breastfeeding practices followed in different regions of India. The present review emphasized the breastfeeding practices followed in rural and urban Indian population.

Our results were inferred from 24 studies on the various aspects of breastfeeding practice in different regions of India. Early breastfeeding initiation has survival benefits and also decreases neonatal mortality [37]. Consistent with the above findings from the systematic review [14, 15, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 32, 33, 35] Aligarh has a population of 40,000 living in 5,480 households. Mothers delivering babies in September 2007 were identified from records of social mobilization workers (Community Mobilization Coordinators or CMCs, early initiation of breastfeeding is in practice so that NMR has declined to 23.5 as compared to 38 in 2019. Contrary to the above findings, some studies have shown delayed breastfeeding initiation due to cultural beliefs, less amount of breast milk, too tired to feed, baby sleep, cesarean section, and lack of awareness. These are some of the mentioned reasons for delayed breastfeeding practice, particularly in rural versus urban populations [15, 18, 26, 34, 36] using a triangulation of qualitative (focus group discussion.

Prelacteal feeds are those foods given to newborns before initiating breastfeeding or before breast milk “comes in”, usually on the first day of life [38]. Because of cultural diversity, the Indian population emphasizes the rural area and still practice prelacteal feeding. The common prelacteal feeds were honey, “ghutti”, sugar, and tea [34, 36] using a triangulation of qualitative (focus group discussion. Not only among mothers and family but this belief is also followed among health providers Anxiety Nurse Midwife (ANM) in a rural setting has proclaimed that despite the change in guidelines, prelacteal feed is still recommended [36]. Reddy et al. highlighted the use of honey [35], risk factors, and interactions of enteric infections and malnutrition and the consequences for child health. Khan et al. cited family customs and relatives’ advice for prelacteal feed [14].

As per WHO, EBF means giving the baby only breast milk for the first 6 months without adding any additional drink, including water or food [39]. Despite the undeniable benefits of EBF, its practice has remained less than desirable. According to Kaushal et al., less than 10% of the study population followed the EBF [34]. In contrast, a study revealed that participants started the weaning practice in less than 4 months and followed the on-demand feeding [15]. Studies from different parts of India have found that the EBF practice was not followed by mothers [17, 18, 21, 25]. Saxena Y et al. found multiple hindering factors for EBF: inadequate mother's milk, cesarean sections, and coercion from elders in the family to start top milk [40].

Weaning practices are the approach of introducing soft, semi-solid, and or solid foods by six months of age along with breast milk [41]. In India, there is an enormous diversity in different regions to start weaning feed, such as "Dalia", "Khichdi", "ragi sari", cow's milk, and rice. The early weaning hinders the EBF practice [20, 23, 34]. Additionally, inadequate knowledge about weaning and weaning foods were the limiting factors contributing to suboptimal weaning practices leading to suboptimal growth of an infant [34]. Accordingly, the risk for infections, undernutrition, and child morbidity and mortality has been increased [42, 43]. Emphasis should be on assessing proper, regionally available weaning diets and a well-planned regional weaning education, a common element of well-baby programs [44].

This review shows that breastfeeding practice in India is common. However, many breastfeeding and weaning methods are not conducive to the child’s growth and development. The study shows that the early onset of breastfeeding is commonly being practiced, but colostrum is still being discarded. It is necessary to address the myths of prelacteal feed that delay the early initiation of breastfeeding by postnatal mothers. Health care workers, especially nurses, Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM), primary health centers, community health centers, emphasize the importance of early initiation of breastfeeding, EBF, and weaning practices.

We recommend that future researchers perform a meta-analysis to provide higher-level evidence from India. Also, a transcultural study will be appropriate to understand differences in cultural practices, which could hinder the early initiation of breastfeeding, EBF, and weaning process that will help plan different intervention modules according to regional practices. We could not access a few full texts of related articles, which might have added strength to the present review.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Author's contributions

Study concept, literature search: Prasuna Jelly, Rakesh Sharma, and Gunjot Arora; Review and data extraction: Prasuna Jelly, Rakesh Sharma, Gunjot Arora, and Suresh K Sharma; Quality assessment, reviewing the final edition: All authors; Results and discussion: Prasuna Jelly, Rakesh Sharma, and Gunjot Arora.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- UNICEF and WHO. Global Breastfeeding Scorecard, 2019 [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326049/WHO-NMH-NHD-19.22-eng.pdf

- UNICEF. Infant and young child feeding - Monitoring for mother and children [Internet]. UNICEF. 2019. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/infant-and-young-child-feeding/

- UNICEF. Global breastfeeding Collective-Tracking Progress for Breastfeeding Policies and Programmes [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/global-bf-scorecard-2017.pdf

- WHO and UNICEF issue new guidance to promote breastfeeding in health facilities globally [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/who-unicef-issue-new-guidance-promote-breastfeeding-globally

- IIPS. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) 2015-16 INDIA [Internet]. Mumbai; 2017. Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/nfhs

- Das A, Mala GS, Singh RS, Majumdar A, Chatterjee R, Chaudhuri I, et al. Prelacteal feeding practice and maintenance of exclusive breast feeding in Bihar, India- Identifying key demographic sections for childhood nutrition interventions: A cross-sectional study. Gates Open Research. 2019; 3:1. [DOI:10.12688/gatesopenres.12862.3] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kumar Raja R. Breastfeeding practice at its low in India [Internet]. 2016. https://www.bpni.org/Article/Breastfeeding-practice-at-its-low-in-India.pdf

- Roy S, Simalti A, Nair B. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and knowledge related to breastfeeding among mothers attending immunization center and well-baby clinic. Acta Medica International. 2018; 5(2):79-83. [DOI:10.4103/ami.ami_56_18]

- Al-Amoud MM. Breastfeeding practice among women attending primary health centers in Riyadh. Journal of Family and Community Medicine. 2003; 10(1):19-30. [PMID]

- Aguayo VM, Menon P. Stop stunting: Improving child feeding, women’s nutrition and household sanitation in South Asia. Maternal and Child Nutrition. 2016; 12(S 1):3-11. [DOI:10.1111/mcn.12283] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mehlawat U, Puri S, Rekhi TK. Breastfeeding practices among mothers at birth and at 6 months in urban areas of Delhi-Ncr, India. Jurnal Gizi dan Pangan. 2020; 15(2):101-8. [DOI:10.25182/jgp.2020.15.2.101-108]

- Oakley L, Baker CP, Addanki S, Gupta V, Walia GK, Aggarwal A, et al. Is increasing urbanicity associated with changes in breastfeeding duration in rural India? An analysis of cross-sectional household data from the Andhra Pradesh children and parents study. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(9):e016331. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016331] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Khan ME. Breast-feeding and weaning practices in India. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 1990; 5(1):71-88. [DOI:10.18356/76fe5e12-en] [PMID]

- Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [Internet]. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- Khan Z, Mehnaz S, Khalique N, Ansari MA, Siddiqui AR. Poor perinatal care practices in urban slums: Possible role of social mobilization networks. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2009; 34(2):102-7. [DOI:10.4103/0970-0218.51229] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kalita D, Borah M. Current practices on infant feeding in rural areas of Assam, India: A community based cross sectional study. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health. 2016; 3(6):1454-60. [DOI:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20161610]

- Veeranki SP, Nishimura H, Krupp K, Gowda S, Arun A, Madhivanan P. Suboptimal breastfeeding practices among women in rural and low-resource settings: A study of women in rural Mysore, India. Annals of Global Health. 2017; 83(3-4):577-83. [DOI:10.1016/j.aogh.2017.10.012] [PMID]

- Junaid M, Patil S. Breastfeeding practices among lactating mothers of a rural area of central India: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health. 2018; 5(12):5242-5. [DOI:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20184797]

- Randhawa A, Chaudhary N, Gill B, Singh A, Garg V, Balgir R. A population-based cross-sectional study to determine the practices of breastfeeding among the lactating mothers of Patiala city. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2019; 8(10):3207. [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_549_19] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Liaquath Ali F, Govindasamy R, Soubramanian S. A study on feeding practices among mothers with children aged less than two years in rural area of Kancheepuram District, Tamil Nadu. International Journal of Community Medicine. 2019; 6(8):3471-6. [DOI:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20193474]

- Bhanderi D, Choudhary S. A community based study of feeding & weaning practices in under five children in semi urban community of Gujarat. National Journal of Community Medicine. 2011; 2(2):277-83. http://njcmindia.org/uploads/2-2_277-283.pdf

- Shashi K, BR D, Bharti, Sumit C. Breast feeding practices in a rural area of Haryana, India. International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies. 2015; 2(8):29-32. http://www.ijims.com/uploads/e156c27590c8f03779815.pdf

- Young MF, Nguyen P, Kachwaha S, Tran Mai L, Ghosh S, Agrawal R, et al. It takes a village: An empirical analysis of how husbands, mothers-in-law, health workers, and mothers influence breastfeeding practices in Uttar Pradesh, India. Maternal and Child Nutrition. 2020; 16(2):e12892. [DOI:10.1111/mcn.12892] [PMCID]

- Rudrappa S, Raju HN, Kavya MY. To study the knowledge, attitude and practice of breastfeeding among postnatal mothers in a tertiary care center of south India. Indian Journal of Child Health. 2020; 7(3):113-6. [DOI:10.32677/IJCH.2020.v07.i03.005]

- Gadhavi K, Deo R. Delayed onset of breastfeeding: What is stopping us? International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics. 2020; 7(10):2021-5. [DOI:10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20204046]

- Madhu K, Chowdary S, Masthi R. Breast feeding practices and newborn care in rural areas: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2009; 34(3):243-6. [DOI:10.4103/0970-0218.55292] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sinhababu A, Mukhopadhyay DK, Panja TK, Saren AB, Mandal NK, Biswas AB. Infant-and young child-feeding practices in Bankura district, West Bengal, India. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2010; 28(3):294-9. [DOI:10.3329/jhpn.v28i3.5559] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Shaili V, Parul S, Kandpal SD, Jayanti S, Anurag S, Vipul N. A community based study on breastfeeding practices in a rural area of Uttarakhand. National Journal of Community Medicine. 2012; 3(2):283-7. http://njcmindia.org/uploads/3-2_283-287.pdf

- Khan YM, Khan A. Breast feeding practices among Kashmiri population. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Food Sciences. 2013; 1(1):7-20. https://ajouronline.com/index.php/AJAFS/article/view/63

- Sinha LN, Kaur P, Gupta R, Dalpath S, Goyal V, Murhekar M. Newborn care practices and home-based postnatal newborn care programme- Mewat, Haryana, India, 2013. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response (WPSAR). 2014; 5(3):22-9. [DOI:10.5365/wpsar.2014.5.1.006] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Swetha R, Ravikumar J, Nageswara Rao R. Study of breastfeeding practices in coastal region of South India: a cross sectional study. International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics. 2017; 1(2):74-8. [DOI:10.5455/2349-3291.ijcp20140812]

- Meharda B, Dixit M. A community based cross sectional study of breastfeeding practices of nursing mothers at block Phagi, district Jaipur (Rajasthan). International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health. 2015; 2(4):404-8. [DOI:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20150936]

- Satija M, Sharma S, Chaudhary A, Kaushal P, Girdhar S. Infant and young child feeding practices in a rural area of North India. Asian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2015; 6(6):60-5. [DOI:10.3126/ajms.v6i6.12067]

- Reddy SN, Sindhu KN, Ramanujam K, Bose A, Kang G, Mohan VR. Exclusive breastfeeding practices in an urban settlement of Vellore, southern India: Findings from the MAL-ED birth cohort. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2019; 14:29. [DOI:10.1186/s13006-019-0222-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kaushal M, Aggarwal R, Singal A, Shukla H, Kapoor SK, Paul VK. Breastfeeding practices and health-seeking behavior for neonatal sickness in a rural community. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2005; 51(6):366-76. [DOI:10.1093/tropej/fmi035] [PMID]

- Kesterton AJ, Cleland J. Neonatal care in rural Karnataka: Healthy and harmful practices, the potential for change. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2009; 9:20. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2393-9-20] [PMID] [PMCID]

- George M, Johnson AR, Basil RC, Murthy SN, Agrawal T. Postpartum and newborn care-A qualitative study. Indian Journal of Community Health. 2018; 30(2):163-5. https://www.iapsmupuk.org/journal/index.php/IJCH/article/view/871

- WHO. Early initiation of breastfeeding: The key to survival and beyond [Internet]. 2010. https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2010/Technical brief. Early initiation of breastfeeding.pdf

- McKenna KM, Shankar RT. The practice of prelacteal feeding to newborns among Hindu and Muslim families. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2009; 54(1):78-81. [DOI:10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.07.012] [PMID]

- WHO. Infant and young child feeding [Internet]. 2021 [9 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding

- Saxena V, Kumari R. Infant and young child feeding - knowledge and practices of ASHA workers of Doiwala Block, Dehradun District. Indian Journal of Community Health. 2014; 26(1):68-75. https://www.iapsmupuk.org/journal/index.php/IJCH/article/view/376/376

- Tahiru R, Agbozo F, Garti H, Abubakari A. Exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers with twins in the tamale metropolis. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2020; 2020:5605437. [DOI:10.1155/2020/5605437] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Saxena V, Kumar P. Complementary feeding practices in rural community: A study from block Doiwala district Dehradun. Indian Journal of Basic and Applied Medical Research. 2014; 3(2):358-63. https://www.ijbamr.com/assets/images/issues/pdf/358-363.pdf.pdf

- Saxena V, Jelly P, Sharma R. An exploratory study on traditional practices of families during the perinatal period among traditional birth attendants in Uttarakhand. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2020; 9(1):156-61. [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_697_19] [PMID] [PMCID]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2021/01/24 | Accepted: 2021/05/11 | Published: 2022/01/1

Received: 2021/01/24 | Accepted: 2021/05/11 | Published: 2022/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |