Tue, Feb 3, 2026

Volume 31, Issue 1 (12-2021)

JHNM 2021, 31(1): 61-67 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

jahan F, Nematolahi S. Effect of a Quality of Life Education Program on Psychological Well-Being and Adherence to Treatment of Diabetic Patients. JHNM 2021; 31 (1) :61-67

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-1528-en.html

URL: http://hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-1528-en.html

1- Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, Semnan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Semnan, Iran , Faeze.jahan@gmail.com

2- Master of Clinical Psychology, Semnan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Semnan, Iran

2- Master of Clinical Psychology, Semnan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Semnan, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 489 kb]

(1395 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3115 Views)

Full-Text: (1591 Views)

Introduction

iabetes is a chronic disease and one of the most common diseases in the world. Despite significant advances in medical science, there is still no definitive and short-term treatment for it. This disease is a constant struggle for the sufferer because affected people are threatened by the presence of an incurable disease and the possibility of severe complications and shortening of life span [1]. The prevalence of diabetes in the world is projected to increase from 4% in 1995 to 5.4% in 2025, during which the number of affected population will increase by 122% [2]. Chronic hyperglycemia causes damage, dysfunction, and failure of various body organs, especially the eyes, kidneys, nerves, and cardiovascular system [3].

In recent years, developments in the treatment of psychological disorders and chronic diseases such as diabetes have indicated the role of psychological interventions, including interventions based on improving the Quality of Life (QoL), in controlling and improving the disease. Health-related QoL is a concept that has found a special place in psychological research in recent years. There are various definitions for health-related QoL. Some define it as an individual’s ability to manage life [4], while others define it as a descriptive concept that refers to the health and promotion of emotional, social, and physical aspects of individuals and their ability to perform daily tasks [5].However, the most accepted definition in this area is perhaps provided by the World Health Organization (WHO): “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.”

QoL is a purely subjective issue and cannot be seen by others and is based on people’s understanding of various aspects of life [6].One of the issues in QoL is Psychological Well-being (PWB). It refers to what a person needs for his or her well-being and health [7]. In other words, PWB generally deals with a person’s physical and mental health and general satisfaction with life, which also includes concepts such as job satisfaction. In other words, PWB is a broad concept that covers a variety of issues [8]. The PWB approach examines the existential challenges of life and places great emphasis on human evolution and progress [9].

One of the important goals of educating the patients and increasing their QoL is to encourage them to adhere to the treatment regimens [10]. One of the major problems in the proper control of diabetes is the patients’ lack of adherence to treatment regimens, such that in some studies, the rate of non-adherence to treatment in diabetic patients is 23%-93%, and some have been reported in one-third to three-quarters of patients [11].Low adherence of patients is one of the biggest challenges for success in the treatment of chronic diseases such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes [12]. In some chronic diseases, multidrug regimens may need to be used. In diabetes, it is often necessary to use a multidrug regimen to control blood sugar, blood pressure, and blood lipid. Patients’ adherence to prescribed medications is a vital factor in achieving metabolic control [13]. This study aimed to determine the effect of QoL education on adherence to the treatment regime and the PWB of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Materials and Methods

This is a pilot study with a quasi-experimental design. The study samples were 30 patients with type 2 diabetes referred to health centers in Semnan City during the six months from March to September 2018. The sampling was done by using a convenience sampling technique, and the sample size was determined based on the minimum sample size used in quasi-experimental studies [14]. The inclusion criteria were diagnosis of type 2 diabetes by a physician, aged 30-60 years (due to having ability to better cooperate in training sessions), having the disease at least one year before the study, willingness and informed consent to participate in the study, referring to one of the study health centers, and having a medical record. Absence from more than two interventional sessions and unwillingness to continue participating in the study were the exclusion criteria. The participants were systematically divided into two groups of intervention (n=15) and control (n=15).

One of the data collection tools was the General Adherence Scale (GAS), designed by Hayes in 1994. It measures the patient’s willingness to adhere to a doctor’s advice in general. It has 5 items rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale where two items of 1 and 3 have reversed scoring [15]. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of this questionnaire is 0.68. In the present study, the Cronbach alpha for measuring the reliability of Its Persian version was reported as 0.83. The other tool is the Psychological Well-being Scale, Short-Form (PWBS-SF).It was designed by Ryff in 1989 and revised in 2002 by Rashid and Anjum [16, 17]. It has 18 items and 6 subscales: autonomy (ability to pursue desires and act on personal principles), environmental mastery (ability to manage everyday affairs, especially daily life issues), personal growth (feeling that potential talents and abilities are realized over time and throughout life), positive relations with others (people who are important in a person’s life),having a purpose in life (having goals that give direction and meaning to one’s life),and self-acceptance (being pleased with how things have turned out). It is a self-assessment tool with items rated on a 6-point scale from 1=strongly agree to 6=strongly disagree. Higher scores indicate better PWB [18]. This tool has been used in many studies [19, 20, 21]. In the present study, its Cronbach alpha value was obtained 0.75.

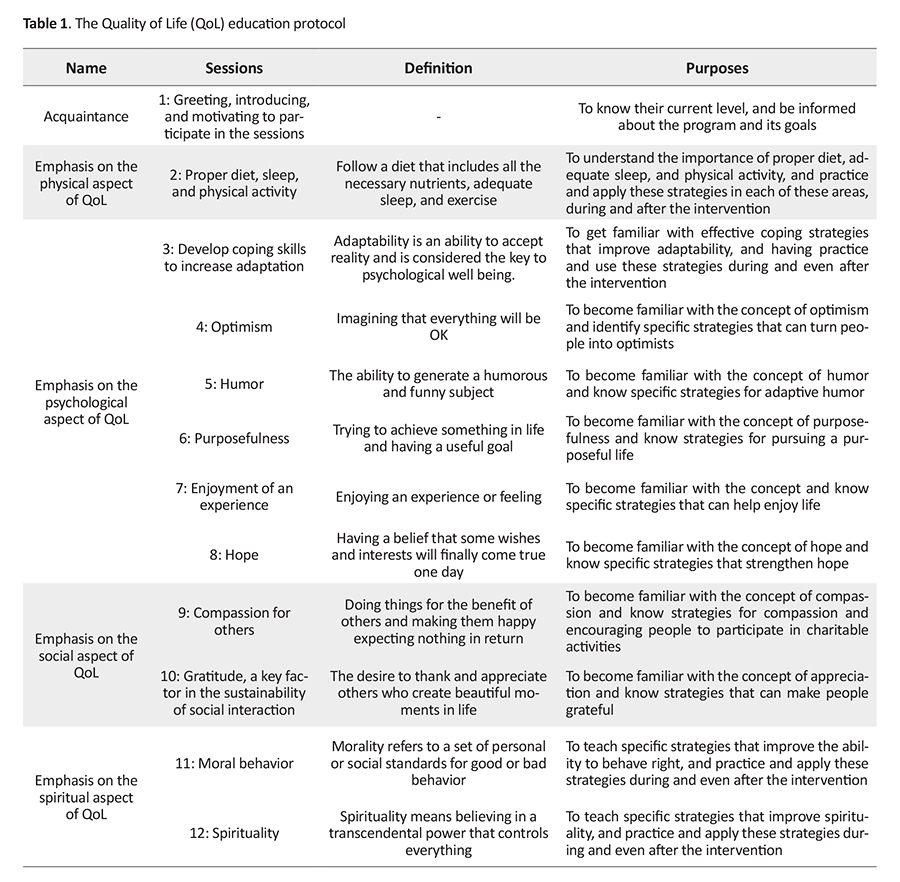

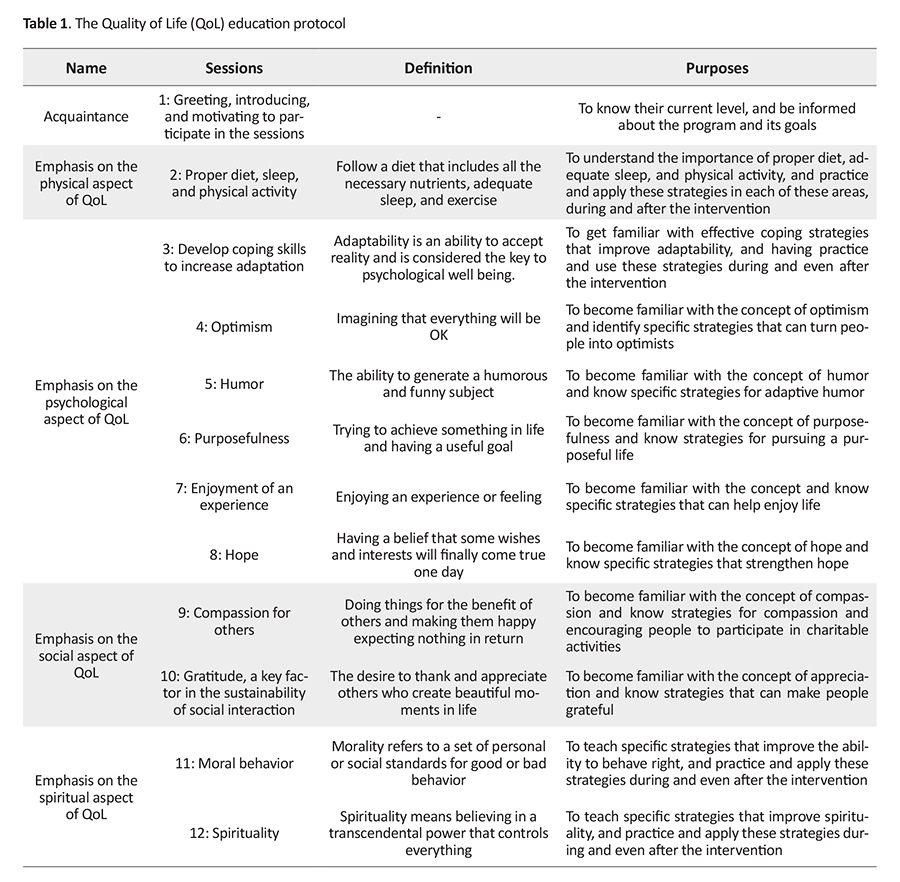

To observe ethical considerations, after obtaining the consent from participants, the study objectives and methods were explained to them and they were assured that their information was kept confidential, and was free to leave the study at any time. After baseline assessments, the intervention group received QoL education for 6weeks, twelve 90-min sessions, while the control group received no intervention. However, they received an educational program after the end of the study. Babaei’s QoL educational protocol [14] was used in the educational sessions. The summary of the sessions is presented in Table 1.

The MANCOVA was used to evaluate the effect of QoL intervention. For checking the assumptions of ANCOVA, Box’s M test was used to assess the equality of covariance matrices, and Levene’s test to measure the equality of variances.

Results

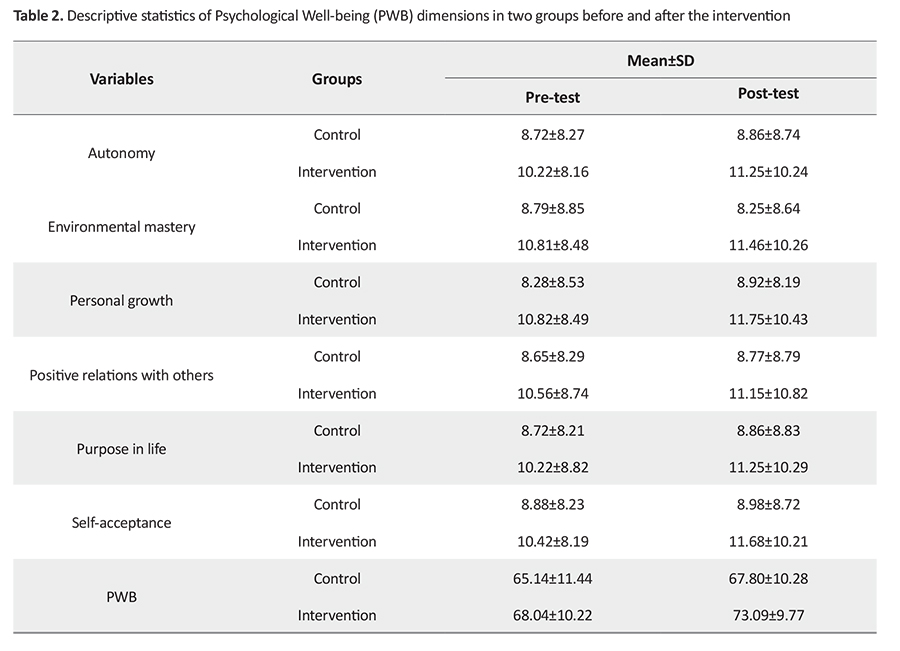

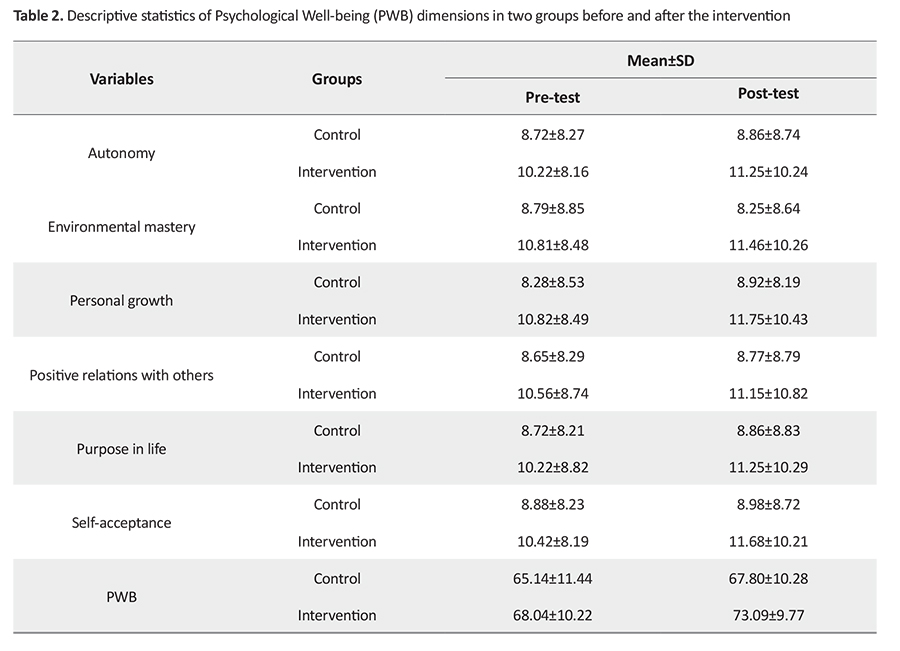

Of 30 patients, 15 were men and 15 women with a Mean±SD age of 43.5 (13.5) years. All were married and 10% had a high school diploma, 70% a bachelor’s degree, and 20% a master’s degree. In Table 2, the descriptive indicators of the two groups are presented in each of the subscales of PWBS-SF in pre-test and post-test phases. As can be seen, in the intervention group, the mean score of adherence to treatment and PWB in patients is higher than in the control group.

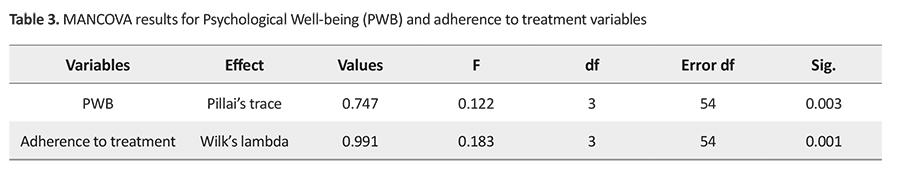

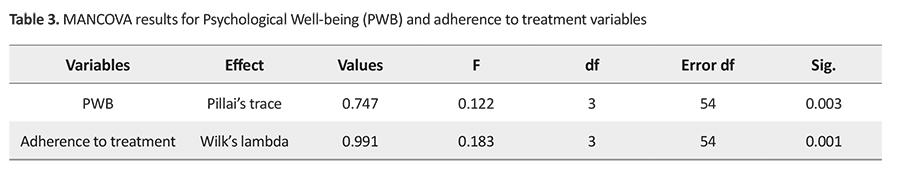

Box’s M test showed the equality of covariance matrices of adherence to treatment between the two groups (Box’s M=12.755, F=1.96, P>0.05); Levene’s test results showed the equality of variances; the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results showed the normal distribution of data. Hence, MANCOVA was conducted for comparing the effect of QoL intervention on adherence to treatment in diabetic patients. Its results are presented in Table 3, which indicates that the QoL educational intervention was effective in improving adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes (F=0.183, P=0.001). For the PWB variable, Box’s M test showed no equality of covariance matrices (Box’s M=15.2, F=1.58, P<0.05); therefore, the results of Pillai’s trace were reported.

Levene’s test results showed the equality of variances (P>0.05), and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results showed the normal distribution of data. The results of MANCOVA showed that the QoL educational intervention was effective in improving the PWB of diabetic patients (F=0.122, P<0.001).

Discussion

According to the findings of the present study, the number of diabetic patients who received QoL education significantly increased their adherence to treatment. This finding is consistent with the results of some similar studies [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30]. Gregg et al. showed that adherence to the treatment regimen in people with type 2 diabetes is influenced by QoL, social and family support, and patients’ beliefs and individual values [31]. Their findings indicated that people with diabetes need support and help.

Family members have an important role in treatment adherence of patients and are considered as sources of support without which it is difficult and sometimes impossible for patients to adhere to a treatment regimen. Besides, the support of the treatment team, adequate education and information on diabetes and its complications, and the elimination of information needs and ambiguities in the form of self-care group sessions are also important in improving treatment adherence. Health care providers are unable to facilitate patients’ treatment adherence. They focus more on providing clinical care and treatment for them and less on QoL education and counseling and do not have enough time to listen to patients’ problems let alone teaching patients and their families. However, patients demand a coordinated care model and health care interactions; a model of care that is followed by discussion and understanding and is based on participatory decision making according to individual preferences and along with the provision of alternative treatment options to patients.

Lack of self-management training has been reportedin other studies as one of the major barriers to adhering to the diabetes treatment regime. Cacioppo et al. also stated that lack of information and poor-quality care is a common barrier to continued care and treatment adherence in developing countries [32]. Bautista et al. reported self-reliance and active participation in self-care planning to be important factors for greater self-care and treatment adherence in patients [33].

The results of our study showed that QoL education caused a significant increase in PWB scores of diabetic patients. This finding is consistent with the results of other studies [32, 33, 34]. Awareness of health care providers about the importance of providing such training can have positive results in improving the provision of services to patients. By using these results, nurses, counselors, and health care providers can use effective QoL education in chronic patients and take effective steps to improve their condition and reduce their dependence on medical staff and enable them to manage their problems. The QoL education can lead to a sense of self-esteem and self-sufficiency in the patients and they can gain strength, energy, ability to perform daily activities, and self-care. Therefore, their view of their abilities and surroundings becomes more positive and they can benefit from higher PWB. One possible factor in increasing the PWB of these patients was their feeling of controlling the disease. Patients feel less mentally controlled due to having a long and chronic illness and feeling helpless due to depression and having negative thoughts about their abilities. By self-management technique, these patients are taught that the symptoms of increased/decreased blood sugar area kind of daily experiences, and they can manage different daily experiences, and control the signs and symptoms of the disease by identifying the triggers. Therefore, by increasing the sense of control over symptoms and reducing the incidence of blood sugar fluctuations, the patients’ QoL improves [34].

Due to the high level of stress in society and the lack of supporting systems in this field, it is suggested that further studies be conducted to determine the most effective educational methods for the improvement of PWB in diabetic patients. Addressing psychological factors such as QoL can improve the factors affecting self-care and, thus, play an important role in controlling diabetes. Therefore, it is suggested that, in addition to medication, special attention be paid to improve the QoL of these patients. Due to the low number of samples in this pilot study, it is suggested that QoL intervention on diabetic patients in future studies be performed with a larger sample size to have higher generalizability. Another limitation of this study was that it was performed on type 2 diabetic patients referred to two health centers in one city; hence, the results cannot be generalized to all type 2 diabetic patients in the country. Moreover, the mental conditions of the subjects may be affected by their answers to the questions.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present study has Ethical approval (Code: IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.185). The study objectives and procedure were explained to all participants, and their written informed consent was obtained.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Data collection: Saeed Nemtollah; Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, and Data analysis, Writing – review & editing: Faezeh Jahan and Saeed Nemtollah.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Hospital Staff in Semnan and all patients for their cooperation.

References

iabetes is a chronic disease and one of the most common diseases in the world. Despite significant advances in medical science, there is still no definitive and short-term treatment for it. This disease is a constant struggle for the sufferer because affected people are threatened by the presence of an incurable disease and the possibility of severe complications and shortening of life span [1]. The prevalence of diabetes in the world is projected to increase from 4% in 1995 to 5.4% in 2025, during which the number of affected population will increase by 122% [2]. Chronic hyperglycemia causes damage, dysfunction, and failure of various body organs, especially the eyes, kidneys, nerves, and cardiovascular system [3].

In recent years, developments in the treatment of psychological disorders and chronic diseases such as diabetes have indicated the role of psychological interventions, including interventions based on improving the Quality of Life (QoL), in controlling and improving the disease. Health-related QoL is a concept that has found a special place in psychological research in recent years. There are various definitions for health-related QoL. Some define it as an individual’s ability to manage life [4], while others define it as a descriptive concept that refers to the health and promotion of emotional, social, and physical aspects of individuals and their ability to perform daily tasks [5].However, the most accepted definition in this area is perhaps provided by the World Health Organization (WHO): “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.”

QoL is a purely subjective issue and cannot be seen by others and is based on people’s understanding of various aspects of life [6].One of the issues in QoL is Psychological Well-being (PWB). It refers to what a person needs for his or her well-being and health [7]. In other words, PWB generally deals with a person’s physical and mental health and general satisfaction with life, which also includes concepts such as job satisfaction. In other words, PWB is a broad concept that covers a variety of issues [8]. The PWB approach examines the existential challenges of life and places great emphasis on human evolution and progress [9].

One of the important goals of educating the patients and increasing their QoL is to encourage them to adhere to the treatment regimens [10]. One of the major problems in the proper control of diabetes is the patients’ lack of adherence to treatment regimens, such that in some studies, the rate of non-adherence to treatment in diabetic patients is 23%-93%, and some have been reported in one-third to three-quarters of patients [11].Low adherence of patients is one of the biggest challenges for success in the treatment of chronic diseases such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes [12]. In some chronic diseases, multidrug regimens may need to be used. In diabetes, it is often necessary to use a multidrug regimen to control blood sugar, blood pressure, and blood lipid. Patients’ adherence to prescribed medications is a vital factor in achieving metabolic control [13]. This study aimed to determine the effect of QoL education on adherence to the treatment regime and the PWB of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Materials and Methods

This is a pilot study with a quasi-experimental design. The study samples were 30 patients with type 2 diabetes referred to health centers in Semnan City during the six months from March to September 2018. The sampling was done by using a convenience sampling technique, and the sample size was determined based on the minimum sample size used in quasi-experimental studies [14]. The inclusion criteria were diagnosis of type 2 diabetes by a physician, aged 30-60 years (due to having ability to better cooperate in training sessions), having the disease at least one year before the study, willingness and informed consent to participate in the study, referring to one of the study health centers, and having a medical record. Absence from more than two interventional sessions and unwillingness to continue participating in the study were the exclusion criteria. The participants were systematically divided into two groups of intervention (n=15) and control (n=15).

One of the data collection tools was the General Adherence Scale (GAS), designed by Hayes in 1994. It measures the patient’s willingness to adhere to a doctor’s advice in general. It has 5 items rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale where two items of 1 and 3 have reversed scoring [15]. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of this questionnaire is 0.68. In the present study, the Cronbach alpha for measuring the reliability of Its Persian version was reported as 0.83. The other tool is the Psychological Well-being Scale, Short-Form (PWBS-SF).It was designed by Ryff in 1989 and revised in 2002 by Rashid and Anjum [16, 17]. It has 18 items and 6 subscales: autonomy (ability to pursue desires and act on personal principles), environmental mastery (ability to manage everyday affairs, especially daily life issues), personal growth (feeling that potential talents and abilities are realized over time and throughout life), positive relations with others (people who are important in a person’s life),having a purpose in life (having goals that give direction and meaning to one’s life),and self-acceptance (being pleased with how things have turned out). It is a self-assessment tool with items rated on a 6-point scale from 1=strongly agree to 6=strongly disagree. Higher scores indicate better PWB [18]. This tool has been used in many studies [19, 20, 21]. In the present study, its Cronbach alpha value was obtained 0.75.

To observe ethical considerations, after obtaining the consent from participants, the study objectives and methods were explained to them and they were assured that their information was kept confidential, and was free to leave the study at any time. After baseline assessments, the intervention group received QoL education for 6weeks, twelve 90-min sessions, while the control group received no intervention. However, they received an educational program after the end of the study. Babaei’s QoL educational protocol [14] was used in the educational sessions. The summary of the sessions is presented in Table 1.

The MANCOVA was used to evaluate the effect of QoL intervention. For checking the assumptions of ANCOVA, Box’s M test was used to assess the equality of covariance matrices, and Levene’s test to measure the equality of variances.

Results

Of 30 patients, 15 were men and 15 women with a Mean±SD age of 43.5 (13.5) years. All were married and 10% had a high school diploma, 70% a bachelor’s degree, and 20% a master’s degree. In Table 2, the descriptive indicators of the two groups are presented in each of the subscales of PWBS-SF in pre-test and post-test phases. As can be seen, in the intervention group, the mean score of adherence to treatment and PWB in patients is higher than in the control group.

Box’s M test showed the equality of covariance matrices of adherence to treatment between the two groups (Box’s M=12.755, F=1.96, P>0.05); Levene’s test results showed the equality of variances; the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results showed the normal distribution of data. Hence, MANCOVA was conducted for comparing the effect of QoL intervention on adherence to treatment in diabetic patients. Its results are presented in Table 3, which indicates that the QoL educational intervention was effective in improving adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes (F=0.183, P=0.001). For the PWB variable, Box’s M test showed no equality of covariance matrices (Box’s M=15.2, F=1.58, P<0.05); therefore, the results of Pillai’s trace were reported.

Levene’s test results showed the equality of variances (P>0.05), and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results showed the normal distribution of data. The results of MANCOVA showed that the QoL educational intervention was effective in improving the PWB of diabetic patients (F=0.122, P<0.001).

Discussion

According to the findings of the present study, the number of diabetic patients who received QoL education significantly increased their adherence to treatment. This finding is consistent with the results of some similar studies [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30]. Gregg et al. showed that adherence to the treatment regimen in people with type 2 diabetes is influenced by QoL, social and family support, and patients’ beliefs and individual values [31]. Their findings indicated that people with diabetes need support and help.

Family members have an important role in treatment adherence of patients and are considered as sources of support without which it is difficult and sometimes impossible for patients to adhere to a treatment regimen. Besides, the support of the treatment team, adequate education and information on diabetes and its complications, and the elimination of information needs and ambiguities in the form of self-care group sessions are also important in improving treatment adherence. Health care providers are unable to facilitate patients’ treatment adherence. They focus more on providing clinical care and treatment for them and less on QoL education and counseling and do not have enough time to listen to patients’ problems let alone teaching patients and their families. However, patients demand a coordinated care model and health care interactions; a model of care that is followed by discussion and understanding and is based on participatory decision making according to individual preferences and along with the provision of alternative treatment options to patients.

Lack of self-management training has been reportedin other studies as one of the major barriers to adhering to the diabetes treatment regime. Cacioppo et al. also stated that lack of information and poor-quality care is a common barrier to continued care and treatment adherence in developing countries [32]. Bautista et al. reported self-reliance and active participation in self-care planning to be important factors for greater self-care and treatment adherence in patients [33].

The results of our study showed that QoL education caused a significant increase in PWB scores of diabetic patients. This finding is consistent with the results of other studies [32, 33, 34]. Awareness of health care providers about the importance of providing such training can have positive results in improving the provision of services to patients. By using these results, nurses, counselors, and health care providers can use effective QoL education in chronic patients and take effective steps to improve their condition and reduce their dependence on medical staff and enable them to manage their problems. The QoL education can lead to a sense of self-esteem and self-sufficiency in the patients and they can gain strength, energy, ability to perform daily activities, and self-care. Therefore, their view of their abilities and surroundings becomes more positive and they can benefit from higher PWB. One possible factor in increasing the PWB of these patients was their feeling of controlling the disease. Patients feel less mentally controlled due to having a long and chronic illness and feeling helpless due to depression and having negative thoughts about their abilities. By self-management technique, these patients are taught that the symptoms of increased/decreased blood sugar area kind of daily experiences, and they can manage different daily experiences, and control the signs and symptoms of the disease by identifying the triggers. Therefore, by increasing the sense of control over symptoms and reducing the incidence of blood sugar fluctuations, the patients’ QoL improves [34].

Due to the high level of stress in society and the lack of supporting systems in this field, it is suggested that further studies be conducted to determine the most effective educational methods for the improvement of PWB in diabetic patients. Addressing psychological factors such as QoL can improve the factors affecting self-care and, thus, play an important role in controlling diabetes. Therefore, it is suggested that, in addition to medication, special attention be paid to improve the QoL of these patients. Due to the low number of samples in this pilot study, it is suggested that QoL intervention on diabetic patients in future studies be performed with a larger sample size to have higher generalizability. Another limitation of this study was that it was performed on type 2 diabetic patients referred to two health centers in one city; hence, the results cannot be generalized to all type 2 diabetic patients in the country. Moreover, the mental conditions of the subjects may be affected by their answers to the questions.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present study has Ethical approval (Code: IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.185). The study objectives and procedure were explained to all participants, and their written informed consent was obtained.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Data collection: Saeed Nemtollah; Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, and Data analysis, Writing – review & editing: Faezeh Jahan and Saeed Nemtollah.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Hospital Staff in Semnan and all patients for their cooperation.

References

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33(1):62-9. [DOI:10.2337/dc10-S062] [PMID] [PMCID]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2015 abridged for primary care providers. Clinical Diabetes. 2015; 33(2):97-11. [DOI:10.2337/diaclin.33.2.97] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Anjana RM, Deepa M, Pradeepa R, Mahanta J, Narain K, Das HK, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes in 15 states of India: Results from the ICMR-INDIAB population-based cross-sectional study. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2017; 5(8):585-96. [DOI:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30174-2]

- Minet L, Møller S, Vach W, Wagner L, Henriksen JE. Mediating the effect of self-care management intervention in type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of 47 randomised controlled trials. Patient Education and Counselin .2010; 80(1):29-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.033] [PMID]

- Young-Hyman D, De Groot M, Hill-Briggs F, Gonzalez JS, Hood K, Peyrot M. Psychosocial care for people with diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2016; 39(12):2126-40. [DOI:10.2337/dc16-2053] [PMID] [PMCID]

- World Health Organization. WHOQoL-BREF: Introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment: Field trial version, December 1996. World Health Organization; 1996. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291798006667] [PMID]

- Ryff CD, Singer BH. Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2008; 9(1):13-39. [DOI:10.4236/psych.2018.913154]

- Snoek FJ. Quality of Life: A closer look at measuring patients' well-being. Diabetes spectrum. 2000; 13(1):24-8. http://journal.diabetes.org/diabetesspectrum/00v13n1/pg24.htm

- Méndez FJ, Belendez M. Effects of a behavioral intervention on treatment adherence and stress management in adolescents with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1997; 20(9):1370-5. [DOI:10.2337/diacare.20.9.1370] [PMID]

- Kitzler TM, Bachar M, Skrabal F, Kotanko P. Evaluation of treatment adherence in type 1 diabetes: A novel approach. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007; 37(3):207-13. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01771.x] [PMID]

- Moon C, Snyder CR, Rapoff MA. The relationship of hope to childrens asthma treatment adherence. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2007; 2(3):68-94. [DOI:10.1080/17439760701409629]

- DeCoster VA. Challenges of type 2 diabetes and role of health care social work: A neglected area of practice. Health & Social Work. 2001; 26(1):26-37. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/26.1.26

- Elder NC, Muench J. Diabetes care as public health. Journal of Family Practice. 2000; 49(6):513. [DOI:10.1093/hsw/26.1.26] [PMID]

- Ball EM, Banks MB. Determinants of compliance with nasal continuous positive airway pressure treatment applied in a community setting. Sleep Medicine. 2001; 2(3):195-205. [DOI:10.1016/S1389-9457(01)00086-7]

- Luanglath P, Rewtrakunphaiboon W. Determination of a minimum sample size for film-induced tourism research. In: Silpakorn 70th Anniversary International Conference; 2013; Bangkok: Thaland. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Paul_Louangrath/publication/264160342_

- Babaei N, Afrooz GA, Arjmandnia AA. Developing a life quality promoting program and investigation of its effectiveness on mental health and marital satisfaction of mothers with down syndrome daughters. Journal of Family Psychology. 2017 4(1):75-86. [DOI:10.1111/sji.12582]

- Keyes CLM, Shmotkin D, Ryff CD. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002; 82(6):1007-22. [DOI.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007]

- Rashid, T. Positive Psychotherapy. In Lopez, S. J. (Ed.) Positive psychology: Exploring the best in people. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Company; 2008. http://tayyabrashid.com/pdf/ppt.pdf

- Lindfors P, Berntsson L, Lundberg U. Factor structure of Ryff’s psychological well-being scales in Swedish female and male white-collar workers. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006; 40(6):1213-22. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2005.10.016]

- Sefidi FA, Farzad V. [Validated measure of Ryff psychological well-being among students of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences (2009) (Persian)]. The Journal of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences. 2012; 16(1):65-71. http://journal.qums.ac.ir/article-1-1245-en.html

- Shokri O, Kadivar P, Farzad V, Daneshvarpour Z, Dastjerdi R, Paeezi M. [A study of factor structure of 3, 9 and 14-item Persian versions of Ryff's Scales Psychological Well-being in university students (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2008; 14(2):152-61. http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-465-en.html

- Khanjani M, Shahidi SH, Fath-Abadi J, Mazaheri MA, Shokri O. [Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Ryff’s scale of Psychological well-being, short form (18-item) among male and female students (Persian)]. Journal of Thought & Behavior in Clinical Psychology. 2014; 8(32):26-37. https://jtbcp.riau.ac.ir/article_67_652c7a0fcd52b8b3f79a9ecdbc18c5d0.pdf

- Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Cagliero E, Wexler DJ, Delahanty L, Wittenberg E, et al. Depression, self-care, and medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: Relationships across the full range of symptom severity. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30(9):2222-7.[DOI:10.2337/dc07-0158] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Akushevich I, Yashkin AP, Kravchenko J, Fang F, Arbeev K, Sloan F, et al. Identifying the causes of the Changes in the prevalence patterns of diabetes in older US adults: A new trend partitioning approach. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2018; 32(4):362-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.12.014] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Poulsen KM, Pachana NA, McDermott BM. Health professionals’ detection of depression and anxiety in their patients with diabetes: The influence of patient, illness and psychological factors. Journal of Health Psychology. 2016; 21(8):1566-75. [DOI:10.1177/1359105314559618] [PMID]

- Asche C, LaFleur J, Conner C. A review of diabetes treatment adherence and the association with clinical and economic outcomes. Clinical Therapeutics. 2011; 33(1):74-109. [DOI:10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.01.019] [PMID]

- Hoey H, Aanstoot HJ, Chiarelli F, Daneman D, Danne T, Dorchy H, et al. Good metabolic control is associated with better Quality of Life in 2,101 adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001; 24(11):1923-8. [DOI:10.2337/diacare.24.11.1923] [PMID]

- Ayalon L, Gross R, Tabenkin H, Porath A, Heymann A, Porter B. Determinants of Quality of Life in primary care patients with diabetes: Implications for social workers. Health & Social Work. 2008; 33(3):229-36. [DOI:10.1093/hsw/33.3.229] [PMID]

- Creswell JD, Way BM, Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Neural correlates of dispositional mindfulness during affect labeling. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007; 69(6):560-5. [DOI:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180f6171f] [PMID]

- Mantzios M, Giannou K. Group vs. Single mindfulness meditation: Exploring avoidance, impulsivity, and weight management in two separate mindfulness meditation settings. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being. 2014; 6(2):173-91. [DOI:10.1111/aphw.12023] [PMID]

- Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, Glenn-Lawson JL. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007; 75(2):336-43. [DOI:10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.336] [PMID]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. Psychology and Aging. 2010; 25(2):453. [DOI:10.1037/a0017216] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bautista LE, Vera-Cala LM, Colombo C, Smith P. Symptoms of depression and anxiety and adherence to antihypertensive medication. American Journal of Hypertension. 2012; 25(4):505-11. [DOI:10.1038/ajh.2011.256] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tang TS, Gillard ML, Funnell MM, Nwankwo R, Parker E, Spurlock D, et al. Developing a new generation of ongoing diabetes self-management support interventions. The Diabetes Educator. 2005; 31(1):91-7. [DOI:10.1177/0145721704273231] [PMID]

Article Type : Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2020/12/19 | Accepted: 2021/12/29 | Published: 2021/12/29

Received: 2020/12/19 | Accepted: 2021/12/29 | Published: 2021/12/29

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |